Forty Years of Fail

Consoles aren't dead. Alongside the latest devices from Nintendo, Microsoft and Sony, the past several months have seen a proliferation of gaming machines like the Ouya, Nvidia Shield, GameStick, Project Mojo, Wikipad, and others that seek to expand our hardware horizons beyond the usual suspects. These mostly Android-based boxes are bringing something different to the market, but whether or not their unusualness will lead to success is still questionable. Considering that we still don't know whether or not the Wii U can succeed, these things are definite risks.

So, no, consoles aren't dead, but more than a few of them could die soon. And if they do, they wouldn't be the first ones to fizzle out prematurely. Ever since Ralph Baer kicked off the console phenomenon with 1972's Magnavox Odyssey, there have been far more failed attempts to earn a place at the home or handheld gaming table than successful ones. Some of these are well known and lovable losers; othersnot so much. So before anyone starts digging the Ouya, Wii U, or Xbox One an incredibly early grave, we dug through the history books and came back with every console misfire we could find. Brace yourselves for fail.

Fairchild Channel F (1976)

Released in the summer of 1976, the Fairchild Channel F was the first console to use both ROM cartridges and microprocessors. This was revolutionary at the time. See, after the Magnavox Odyssey and its Tennis-style games gave way to Ataris mega-smash Pong, a wave of opportunistic companies flooded the market with machines that were dedicated to playing Pong-style clones. This oversaturation would eventually kill the Channel F, but not before it could introduce some firsts to the industry.

Still, it didnt take long before things started to go downhill. The Channel F and its more varied (though sometimes crude) games were fresh and did quite well to startit was even the first console to have a pause feature--but it soon spurred Atari into pumping more money into its then-upcoming machine, the Atari VCS. That box is best known today as the Atari 2600, and, well, it did everything the Channel F did, but better. Consumers soon flocked to it, and Fairchild couldnt keep up. It discontinued the Channel F in late 1977, just 16 months after it launched. Another company named Zircon would release a redesigned Channel F II years later, but that too was short-lived.

RCA Studio II (1977)

Before Ralph Baer approached rival electronics corporation Magnavox with the first-ever video game console, he went to RCA. He got turned down. As a result, RCA had to live with itself as it watched Magnavox make history, Atari make the first smash hit game, and everyone else profit on the new games market in their wake. Naturally, RCA felt a little bitter, so by early 1977 it decided it would redeem its missed opportunities with its own console: the RCA Studio II.

What it actually did was release what some consider the worst console ever made. The Studio II (the Studio I was an unreleased prototype) housed only 16 games in its two-year lifespan, only played games in black and white, and had one monstrosity of a controller. Seriously, look at it. Not only were its dual controllers just 10-digit keypads with no joysticks, they were built into the console itself. Yes, the Studio II used exchangeable cartridges and came pre-packaged with five games, but the Fairchild Channel F had already beaten it to the market with similar features. The Studio II was an obsolete piece of technology even in 1977, and was steamrolled by the Atari 2600 soon after it launched.

Coleco Telstar Arcade (1977)

Remember those Pong clones we were talking about earlier? Well, before Coleco ultimately hit paydirt with the ColecoVision in the early 80s, it made a whole lot of those. Its Telstar line of consoles was home to about a dozen separate Pong variants in just a three year span, but Coleco decided to shake it up once such simple machines started to go out of style.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

The result was the short-lived Coleco Telstar Arcade, which is one of the few triangular consoles ever made. Each side of the machine was dedicated to a different style of game. One with standard knobs and dials could play Pong clones; another with a toy revolver was for light gun games like Quick Draw; while a third sported a dedicated steering wheel and gear shift--both rarities in their time--for racing games. It was a unique idea as far as simplistic consoles went, but the market was ready to move on when it launched. Coleco only released four games for the system, quickly abandoning it to find greener pastures with the ColecoVision a couple of years later.

Bally Astrocade (1978)

First known as the Bally Home Library Computer, then Bally Professional Arcade, then the Bally Computer System, the Bally Astrocade was designed by Midway--as in, the Mortal Kombat people--and went through a couple of lifespans. It was originally sold by Bally as a competitor to the Atari 2600, but didnt pick up much steam. Eventually Bally sold the device to Astrovision, which repackaged the system and changed its name to the Astrocade. It still couldnt compete with Ataris juggernaut.

Thats not to say the Astrocade didnt have some noteworthy features, though. Like the Channel F, it allowed for separate cartridges, and came with a variety of built-in games. It had a 24-button keypad built onto its front, and it even let users develop simple computer programs in BASIC. Its controller was especially unique--it looked like the handle of a gun, had what may be the first trigger button in gaming history, and put a little dial knob at its top. Nevertheless, the Astrocade never received much developer support, and what games it could get were mostly Atari clones. The console--and Astrocade--died in obscurity as part of the video game crash of 1983.

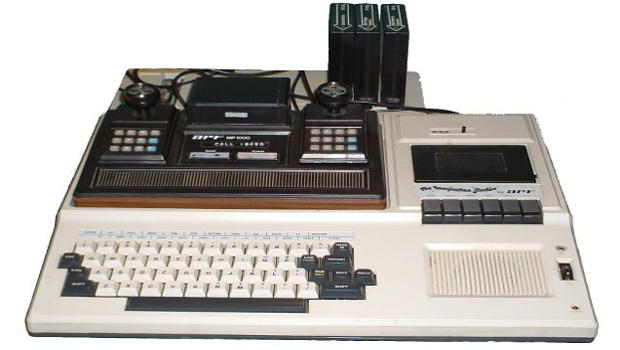

APF Imagination Machine (1978)

Besides having maybe the weirdest name in console history, APF Technologies' Imagination Machine was also one of the most original for its time. It was actually comprised of two separate pieces: an ordinary console called the APF M1000, and an APF MPA-10 add-on component that basically turned the console into a living room PC. It sported a full typewriter-style keyboard and built-in cassette drive, and, similar to the Astrocade, even let players code their own games in the BASIC language.

Unfortunately, anyone who wanted to enjoy this customizable quirkiness had to shell out $600 for the full package. The Atari 2600 still loomed large over most other machines at this time, and the Imagination Machine never stood much of a chance with that asking price. The fact that less than 20 dedicated games were ever released for the console didn't help matters. APF had trafficked in Pong clones before the Imagination Machine, and once those started to die out a short while later, the company did as well.

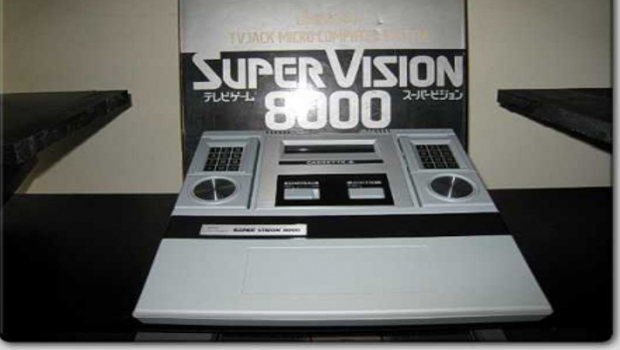

Bandai Super Vision 8000 (1979)

Bandai--yes, that Bandai--had become one of the most popular distributors of Pong-style consoles in Japan by the late 70s with its TV Jack series of machines. But similarly to Coleco and the Telstar Arcade, it decided to expand upon its usual formula with the TV Jack 8000--aka the Super Vision 8000--which was the first programmable Japanese console to take ROM cartridges.

The Super Vision 8000 was an advanced machine for its time, with a powerful processor and a bevy of ports, but it came at a whopping launch price of 60,000 yen (close to $600 today). That, combined with its low number of released games, led to Bandai discontinuing the console within a year of its launch. The company would instead go on to distribute Mattel's more popular Intellivision--which may or may not have taken some design inspiration from the Super Vision 8000--in Japan a short time later.

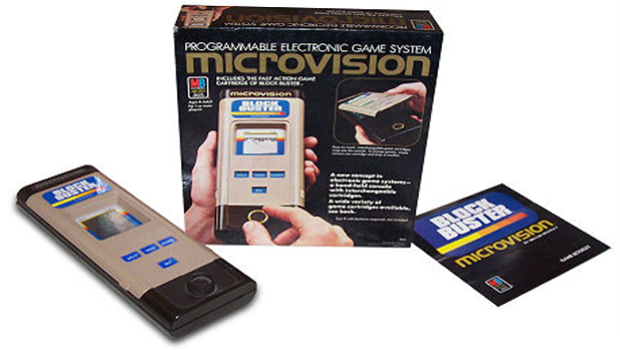

Milton Bradley Microvision (1979)

Gaming was not limited to the living room in its early days, but portable consoles were always a step behind their larger counterparts in terms of innovation. By the late 70s, handheld games mostly came on simple, LED-based consoles that were dedicated to single titles. Think of them like those Pong clones, only smaller and with various other titles like Football, Missile Attack, and others. Mattel was the most popular of the many companies that made such devices.

Milton Bradley changed all of that, though, when it launched the Microvision in 1979. It was the first handheld console to ever use interchangeable cartridges. Yes, this was well before the Game Boy. The bar-shaped device sold fairly well to start, but, like many other technological pioneers, didn't achieve great success in the end. It was built pretty poorly--just look at how small that screen is--and it was easily susceptible to damage. It was only supported by 13 games before it was discontinued in 1983. Everything has to start somewhere, though.

Emerson Arcadia 2001 (1982)

This tiny box from Emerson was made to compete with the Atari 2600 and Intellivison, but found itself doomed from the start. It wasn't exactly powerful for its day, and it didn't have many unique features, but its biggest problems were actually copyright laws. Emerson had a range of popular games like Pac-Man and Defender developed and ready to be released for the system, but in response, Atari sued it and other companies on the ground that it had exclusive rights for such games on its machines.

Atari won. Emerson was soon left with a heap of obscure knockoff titles, virtually no outside developer support, and lots of wasted money before its machine even hit store shelves. When the Atari 5200 and ColecoVision launched around the same time, the Arcadia 2001 lost any chance at success. Emerson stopped producing the console about a year after launch. A handful of clone consoles wound up launching across Eurasia in the following years, which was strange but didn't lead to anything significant.

GCE/Milton Bradley Vectrex (1982)

And now for something completely different. The Vectrex was more or less a miniature arcade cabinet for the living room. It was composed of a typical cartridge-based console and--here's the funky part--a 9-inch CRT monitor that displayed vector graphics. If you don't know what those are, think of what classic games like Asteroids or Tempest looked like. Laugh it up now, but in the early 80s that was the sharpest graphical method around.

The Vectrex's display could only play games in black-and-white on its own, but its games--like the built-in Minestorm--came with colored overlay sheets to spruce things up. It was launched for $200 during the holiday of 1982 and sold well to start, so much so that Milton Bradley bought original distributor GCE a few months later. Unfortunately, as Milton Bradley put its money into expanding the Vectrex's reach, the lethal video game crash of 1983 was starting to take shape. Milton Bradley deeply discounted the Vectrex to hold consumer interest, but ultimately lost millions due to its bad timing. As with many other imaginative machines, the Vectrex was killed off by the crash without reaching its full potential.