Edge Magazine Presents: Game Changers – Xbox 360's billion-dollar ring of death

Edge magazine investigates the infamous red ring of death, the incident that almost toppled the Xbox 360

Presented by Edge, Game Changers is a new editorial series that dives deeper into pivotal moments from console war history, from the original PlayStation launch in 1994, to Xbox’s billion-dollar red ring of death rescue plan. Each episode recaps the industry at the time (The Background), replays key moments as Edge magazine reported them (The Moment), delivers present-day interviews with those involved (The Inside Story) and considers the event's historical impact (What Happened Next?). A new episode of Game Changers will debut at 5pm GMT / 1pm EDT every day this week.

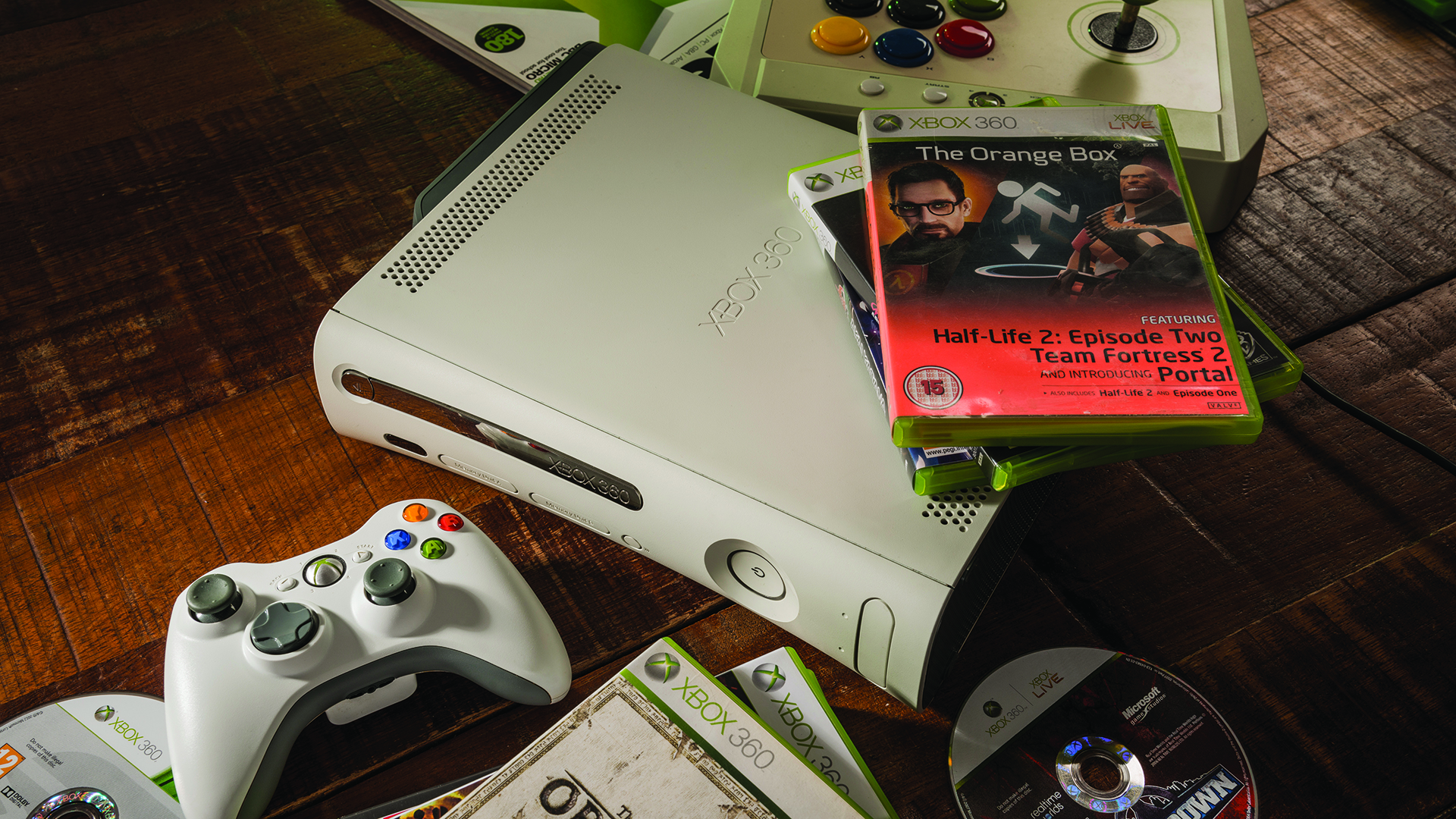

Having put up a plucky fight against PlayStation 2 but ultimately having to watch Sony's console utterly dominate the console landscape, Microsoft knew that it needed as many advantages as possible going into the next generation. Thus, Xbox 360, the world's first HD console, built around the advantages of Xbox Live, stormed out of the gates in late 2005 just under a year ahead of Sony's PS3.

By the time Sony's console was ready, Xbox 360 had delivered Gears Of War, a game whose Unreal Engine-powered visuals overshadowed pretty much everything PS3 could offer at launch. Developer Epic was only one of many third-party studios Microsoft successfully wooed to fight on its side in this latest console war, and Xbox 360's profile continued to build. Everything was going to plan. Until it wasn't.

Not long after Xbox 360's launch, Microsoft began to notice a pattern in hardware returns and repairs. Every consumer electronics item has an 'acceptable' failure rate – it's just the nature of the business – but this console's failure rate was looking unprecedented.

When the Xbox 360 hardware detected an internal failure, it would alert the user by illuminating three of the four lights around its power button in red. There were other configurations of lights for other problems, but this was by far the most common – and it was happening on a major scale, threatening to derail Microsoft's entire console plan just as it was really gathering momentum.

At what should have been a time of triumph, the leaders of the Xbox team were now faced with an existential question. We go back to that moment as Edge reported it, with testimony from those involved, before speaking to former Xbox chief Peter Moore about how Microsoft dealt with an extremely costly problem.

The background: What was wrong with the Xbox 360?

Emerging a year before Sony's PlayStation 3, Microsoft's Xbox 360 saw the company break with the PC architecture of the first Xbox – and also with any kind of sensible naming conventions. It took the IBM core from the middle of the PS3's processor, tinkered with it, then joined three of them together to create Xenon, a processor that did through brute force what Sony's approach did via elegant engineering.

It worked brilliantly, with Xbox 360 going on to host some hugely influential titles, expand the horizons for online console gaming, and sell over 80 million units worldwide. But it nearly collapsed before it really got going.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Microsoft has never gone on record with the precise cause of the 'red ring of death', which saw three of the console's four indicator lights flash red as it stopped working. Speculation as to the cause at the time ranged from a problem in the graphics chip (an ATI design that also handled communications between the CPU, motherboard and RAM) to the more popular theory that hairline cracks were developing in the solder between the GPU and the mainboard, caused by excessive heat.

Whatever the precise reason, failure-rate estimates ranged from 23% to 54%. Microsoft would address the issue by redesigning the console, but first of all it had to do something about the faulty units in circulation. Repairing and replacing all of those consoles cost the company over $1 billion – but it was a price worth paying in order to maintain the Xbox brand.

The moment: What did Edge say about the Red Ring of Death?

"Microsoft denies that there is a systemic problem with Xbox 360 hardware," said Edge in August 2007 (issue 178), noting also that no official figures were available for the number of failed consoles.

No official spokesperson was available for comment either, so Edge was forced to do some sleuthing. Citing reports that repaired 360s had an additional heat sink added to their GPU chip, Edge spoke to Diarmid Andrews, director of console repair firm GT Electronics, about what was causing the failures. "The main problem is the graphics processor," he said. "It can't cool itself properly, gets too hot, and melts the solder that holds it in place. That's when you get the three red lights." Andrews blamed Xbox 360's sleek design for the failures: "The CPU has a good heat sink and it's fine, [but] the DVD-ROM sits right back on the GPU and the heat sink is really quite small. It could use a fan.

"The GPU is sitting on 400 little balls of solder, and that's the connection to the main board. If even one of those balls gets a crack, or gets loose, you'll get three red lights."

Sony had also suffered from a 'yellow light of death' problem with its early PS3 hardware, and Andrews had sympathy for Microsoft. "I repair a lot of Sony's machines as well, but they don't get the criticism," he told Edge. "The biggest surprise is that I can't see how Microsoft have changed the design. I've repaired 360s from the two big Christmas 2006 packs and they haven't solved these problems. They say they have, but they haven't. It's annoying, because the hardware they use is good – the components are solid – and they have good leads and quality DVD drives. It's just a badly designed machine with regards to the GPU."

"Microsoft denies that there is a systemic problem with Xbox 360 hardware," said Edge in August 2007 (issue 178), noting also that no official figures were available for the number of failed consoles.

The problem would be fixed with the introduction of Zephyr, a revised chipset which moved the GPU to an 80nm production process (the original had been at 90nm) and introduced a new heat sink for the GPU. A further revision, Jasper, moved the GPU to a 65nm process. Both of these used less power, were shipped with less hungry power supplies, and generated less heat as a result. Xbox 360 would go through nine such chipset revisions during its life, shrinking its components all the way down to a 45nm process and dropping from a 200-watt power supply to a 120-watt unit.

Speaking in 2015 to IGN, Peter Moore, head of Xbox at the time of the red ring crisis, explained the huge amount of money involved: "We couldn't actually figure out what was going on... I remember going to Robbie Bach, my boss, and saying, 'I think we could have a billion-dollar problem here'. We knew it was heat-related. There were all kinds of fixes. I remember people putting wet towels around the box."

In the midst of the crisis, Microsoft announced a three-year warranty for its machines, something that could cost the company big as failure rates soared. Microsoft CEO Steve Balmer, however, didn't hesitate to sign off on the policy, as Moore recalled: "Steve looked at me and said, 'What have we got to do?' I said, 'We've got to take them all back, and we've got to do this in a first-class way'. He said, 'What's it going to cost?' I remember taking a deep breath, looking at Robbie, and saying, 'We think it's $1.15bn, Steve'. He said, 'Do it'. There was no hesitation."

The inside story: Peter Moore, former head of Xbox, reflects on Microsoft's billion-dollar problem and the steps it took to correct it

"You know, you expect to get your head blown off, but Steve is an astute businessman who recognizes that things can go wrong. Steve saw the big picture: it's not that things go wrong, it's how you fix it."

Peter Moore

Peter Moore, head of Xbox at the time of the 'red ring of death' crisis:

"I don't remember the exact timing, but it was very clear there was a problem. The year following launch we were getting reports from our returns operation of a few more than normal on a percentage basis of defectives coming back, which triggered what was known as the 'red ring of death'. And, look, hardware will fail. But you actually knew what percentage was acceptable. And all of a sudden the numbers start creeping up.

"Then, you know, we're diving in. And at first nobody could really get their arms around what was wrong here. There was, if I recall, a belief that we had to use lead-free solder on the motherboard – maybe that was drying out, maybe we hadn't put enough fans in it. There was all sorts of trial and error. We were doing 24 hours a day to figure out what was going on. But it soon became apparent after a few weeks of watching the numbers come in, looking at the stuff that was coming back, that there was an issue that needed to be dealt with here in order to protect the longevity of the brand.

"We had a problem. We probably needed to do a product recall, but we just can't announce that we need that. We've got to get distribution centres to accept the consoles coming back in. We've got to quickly train for what we think the issue is. And if we're just going to put new motherboards in, or give you a new console, without really understanding what's happening, well, three weeks later it's potentially going to come back again.

"So we had to get everything squared away before we spoke publicly about it. It wasn't that we were hiding anything, but it's no good admitting to the consumer that you have a problem without providing them with a solution. We worked with DHL and FedEx: you would call us, we would FedEx you a box the next day, and you would maybe take your hard drive out, your faceplate off, and then send your console in the prepaid FedEx box to whatever distribution center needed to fix it. And then, once it was fixed, it would be FedEx-ed back to you in order to reduce the time involved with shipping.

"That cost a lot of money. And on top of that, we had to try to keep our third-party publishers happy, because all of a sudden they're going, 'Wait, wait – what? We just spent $20m, $30m, $50m developing these games, and you're telling us this is an issue?' Everything had to be squared away. The communications, the lawyers, as you might imagine... because what is the liability?

"We had a problem. We probably needed to do a product recall, but we just can't announce that we need that"

Peter Moore

"I presented to [then Microsoft CEO] Steve Ballmer: 'This is going to cost us $1.15bn to fix this – to protect the brand, to protect our reputation, to keep this business going'.

"You know, you expect to get your head blown off, but Steve is an astute businessman who recognizes that things can go wrong. Steve saw the big picture: it's not that things go wrong, it's how you fix it. And the moment I had to present the facts and the cost, saying, 'Look, this is what we think that it looks like…' Steve didn't blink, and rightly so.

"Nowadays, when you see that the Xbox brand is worth tens of billions of dollars, that Xbox is one of the top 100 brands in the world, the actions we took all the way back then protected that brand and its value.

"We said then, this is our Tylenol – we're going to stand up, and we've got to put up if we truly believe that this is an industry worth Microsoft being in, and being in as a leader, you know? We're building a brand from nowhere, and the potential for this brand going forward is monstrous. And is [the RROD] a blip? It's more than a blip, and it's more than a speed bump, but fortunately a company like Microsoft has the resources to be able to absorb it. I remember wondering when I was going to crater the stock price. The next day it barely moved.

"We'd budgeted a hundred dollars per unit just for the console to go back [and be fixed and returned]. That was the plan, to deliver a world-class customer experience that made you forget. Once you got your Xbox back, y'know, you forgot what had happened."

What happened next?

For the most part, players did indeed forget, thanks to Microsoft's programme working effectively. There was not only the relief of having to avoid the usual rigmarole involved with faulty goods, but in short order the joy of a functioning console – if not a completely new one – delivered to the door. In 2020 this may seem like basic customer care, but in 2008 it felt like the best service on the planet.

The corporate response to the RROD crisis was a simple but powerful statement: this is something that might sink another company, but Xbox is bigger than that. Forget the razorblade model – Microsoft was betting that you'd still be shaving with Xbox in 20 years, which is what really matters.

Though no one within the company would invite such an incident, the way Microsoft handled a PR nightmare benefited the Xbox brand in some ways, building no small amount of customer loyalty. With 360's extensive selection of high-quality games on top, together with its market-leading online provision, it wasn't a surprise to see Microsoft conclude the generation more or less level with Sony in terms of console sales, having moved from pretender to genuine rival.

The so-called red ring of death was mostly displayed as three illuminated lights on the Xbox 360's power button, not quite completing a circle. Some thought it would be the end of Microsoft in the game console market. But Xbox, even if it cost a billion, found a way out.

You can subscribe to Edge Magazine for only $2.77 an issue and check out the full Edge Presents Game Changers run by going to the Edge homepage.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.