What it's like to grow up with Metal Gear Solid

Metal Gear was like a rite of passage for me as a young man. I don’t just mean one entry in the series – I mean each of the first four games. They all arrived at key moments in my life, always at a point where I was so ready for them, whether I realised it at the time or not. Metal Gear Solid is a formative touchstone of my taste in popular culture, as important to me in that sense as Batman or Star Wars.

I remember the exact moment in the demo of Metal Gear Solid that came with Official PlayStation Magazine that I discovered Snake could choke enemies using the square button, as well as throw them. MGS was probably the first game I played that rewarded experimentation. This was a game that was so confident in the telling of its own story that it felt like the product of a future age, where games were being written by smart people who were trying to create proper characters and fashion stories that got under the skin of their audience.

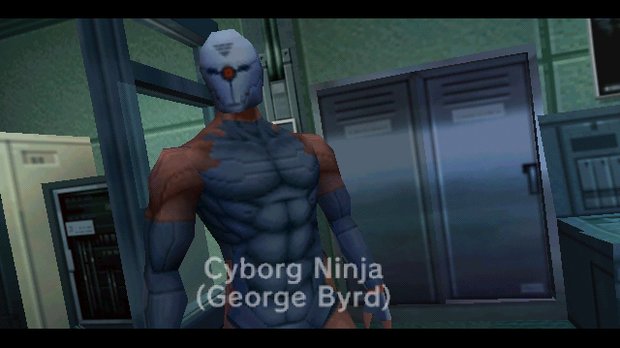

I can’t express enough how extraordinary Metal Gear’s imagery is to a young mind: the nuclear battle tank, the lonely snowscape of Alaska, the green hue of Snake and Campbell as they talk on codec, the cyborg ninja who leaves a trail of bodies behind, this hero with the ludicrous bandana, the array of themed villains who individually were more compelling than the bosses of any other game combined. It was iconic and exotic.

Metal Gear Solid 2 arrived when I was a teenager, exactly the age where I was willing to obsess over its labyrinthine plot and chilling conspiracy theories. I didn’t hate Raiden like the games magazines did at the time, but I didn’t warm to him that much, either. There’s a weirdness to Sons of Liberty’s final act that was unsettling – that you’ve been manipulated by an AI, in the guise of Colonel Campbell, to relive the events of MGS, felt like a grim trick that I spent years pondering afterwards. Its final revelation that the Patriots died 100 years ago led to my first experience of reading fan theories, as I waited six years for Kojima to explain what was going on in MGS4.

I had lost interest in games by the time MGS3 came out – once I played it in 2005, that would never happen again. I’ve always considered Snake Eater the best one, and while I think that’s mostly because it represents the series’ peak in design, my personal connection with that story is probably the real reason I love it. I found Naked Snake a more human, less outlandish hero than Snake. He systematically loses faith in everything in his life: his allies, his lover, his country. Ultimately, learning about the Philosopher’s Legacy would be more relevant to my eventual career path than learning about EU trade policies.

MGS4 was where the real life part of it got incredibly abstract for me. I played it at the end of my first year as a professional writer and somehow found myself in the situation of completing Guns of the Patriots at an event where Kojima himself was present. Indeed, I both interviewed him and completed the game on the day before my 20th birthday; I had to run out of my interview near the end to catch my flight (he politely bowed as I left). That experience, combined with the game itself being a convoluted and extravagant finale to that era of the series, made the whole thing feel hyperreal: to go from being some kid discovering Metal Gear a decade before to finishing the story in the presence of the creator is one of the highlights of my career.

Metal Gear was just always there in my young life, from the first moment I really started getting passionate about games until the moment I became fortunate enough to write about them for a living. I don’t know why Kojima’s series about nuclear battle tanks and gravelly-voiced military heroes feels like it belongs to me – but it absolutely does.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Samuel is now a PR Manager at Frontier Development, but was once a staffer at Future PLC. He was last the Entertainment Editor at TechRadar, but before that he was the UK Editor at PC Gamer. He has also written for GamesRadar in his time. He is also the co-host of the Backpage podcast.