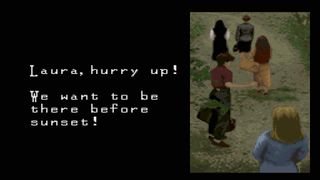

Survival horror has been a mainstay of gaming for decades now; horror and hiding in cupboards go hand-in-hand it seems. However, some of the first seeds of the genre lay in the widely revered and hugely unsettling Japanese point-and-click adventure game, Clock Tower. First released on the SNES in 1995, it sees you playing a 14-year-old orphan girl trapped in a mansion of unknowable terrors, as you desperately try to outpace an unrelenting golden-haired child wielding a gigantic pair of scissors. He can turn up anytime, and does so with reckless glee.

Lacking the fiery arsenal of weapons seen in the likes of Resident Evil, you have to escape using a mix of wits and point-and-click puzzle action (the sort where a slice of ham can mean life or death), plus, plenty of hiding until the horrors pass. While the dexterous mashing of buttons may grant short-lived escape, you'll also find yourself panicked – meaning you're likely to trip up as you run from your tiny, pointy pursuer. Grim, tense and somewhat surreal, Clock Tower introduced a new type of horror to a generation of gamers, and was wildly popular on release. Since then, it has left its bloody, yet restrained, legacy on video games – forming much of the blueprint of survival horror titles.

Whether through the myriad of Clock Tower sequels, or the modern games that cite its simmering tension as an inspiration, such as Alien: Isolation, where you creep around long corridors avoiding the alien, or Amnesia: Dark Descent, in which you are helpless and reduced to hiding in cupboards until the unknowable nasty passes, its impact on modern gaming is undeniable. Plus, with its nine different endings and varied grisly deaths based solely on your choices, it's fair to say Clock Tower has slasher-style DNA, seen in future games like Until Dawn. Coming in at under two hours to play, its choices and randomly generated rooms also provided potential for replays – its endings, as you'd expect, mostly result in death, although some promised the unravelling of dark secrets.

Towering inferno

We spoke to Clock Tower director and creator Hifumi Kono, discussing the making of a horror classic and its origins within the blood-soaked screamscapes of horror movies like cult-classic Suspiria. At school, Kono was an avid player of simulation games, although PC games weren't his favoured choice, he instead preferred tactical and strategic board games released by The Avalon Hill Game Company. His first foray into designing came with a card game he created at university, which used rivalries between the yakuza as a motif.

"That was when I realised the joy of having so many people play something that I had created," comments Kono. "I believe this experience was the catalyst for me to dive into the world of video games." This however, did not form the horrors seen at the heart of Clock Tower. Kono's love of terror was gleaned instead from watching horror movies such as The Exorcist, The Omen and Suspiria in his university dorm room.

"Originally, when I would come up with an idea for a project, I would often break down the structure of a film, anime, or novel that I liked. I would then extract what it was that I found interesting and why, and then structure it out," says Kono. "So when I created Clock Tower, I drew from what fascinated me about horror films like Phenomena and Suspiria. The suspense of being chased and the thrill of hiding from a killer while holding your breath – neither of these aspects existed in video games at the time. That's why I felt it was worth depicting them."

Phenomena, undeniably, shaped Clock Tower. The weird and very gory Dario Argento (of Suspiria fame) film features a young girl who can communicate telepathically with bugs and a stranger wielding a large pair of silver scissors. These lurid, strange images laid down the foundation for what was to become Clock Tower. Kono then went on to work at Japanese company Human Entertainment, which, while not well-known in the West, went on to develop over 80 games. However, getting Clock Tower developed at the company was not as straightforward as it might appear.

If you want in-depth features on classic video games delivered straight to your doorstop, subscribe to Retro Gamer today.

"Back then, Human Entertainment basically had a policy of not developing titles other than sports games. This was understandable as a management policy because it was stable and guaranteed sales, but as a developer, I was starved for an outlet to demonstrate my creativity," Kono elaborates. As well as originating the popular Fire Pro Wrestling series, Human Entertainment was well-known for developing the first ever music rhythm videogame, Dance Aerobics – nearly a decade before the likes of Dance Dance Revolution.

"So, the members of the planning division negotiated with upper management to let us try our hand at an original game. As a result, all the employees decided to hold a competition where anyone could participate freely. It was open to anyone with the condition that the winner would go into full production." Kono decided to design something similar to the 'cinematic live games' made by Human Entertainment at the time, which included SOS, in which you escaped a sinking ship, and its spiritual successor, The Firemen, where you're tasked with saving civilians from a monstrous blaze that erupts at a Christmas party.

"With the exception of Sweet Home, the only horror games that existed at that time were action games with a horror flavour, like Splatterhouse, and that was not my ideal version of horror," he continues. Although Splatterhouse was steeped in horror influences including HP Lovecraft and American slasher movies, it was also a side- scrolling beat-'em-up. Not that Clock Tower does not rely all that much on gore, it leans more towards atmosphere. That said, the mansion itself is rife with all manner of horrible, gothic nasties: dead animal heads, buzzing insects resting on meat and eerie mannequins, to name a few things rendered beautifully in all the glory of 16-bit.

With all that considered, Kono drew up designs embodying his idea of horror, and then went on to win the competition. Following its conception, the next step for Clock Tower was actually developing it. "All of my game designs are based on a series of logical steps, so my process is pretty much solidified at the proposal stage," Kono explains. "So once development started, I only had to focus on things like the flow of the story, creating the map, and event production. However, there was only one problem. Outside of the text adventure genre, the idea of not being able to attack or defeat your enemies was a very foreign concept for games back then."

Fear of the dark

As a result, Kono's ideas received a lot of pushback from the team. Successful titles during the era included the aforementioned Sweet Home, a Capcom survival horror based on the Japanese horror film of the same name. It sees you exploring a cursed, horrible mansion as five film makers. Sweet Home eventually went on to be the inspiration for the hugely successful Resident Evil series – which was originally pitched as a 3D remake of Sweet Home. Haunted house adventure Alone In The Dark, which Kono has previously cited as an inspiration for Clock Tower, was also well received around this time.

However, unlike Clock Tower, both titles included combat as a part of the mechanics. In the context of the time, it's understandable how a non-fighting orientated videogame might seem like quite an unrealistic punt. Clock Tower's player character, Jennifer, is just a regular teenage girl. She moves at a pace that is punishingly slow, she gets freaked out and it takes her an age to climb to safety. This also turned out to be one of the aspects of the game that is most frightening. It leaves running away as your only option, and obstacles that could be jumped over or shot down in other games, present life-ending threats as you stagger haplessly away from your stalker.

"Additionally, the leadership system with directors and team members wasn't clearly established at Human Entertainment back then, making it unclear who had the right to make the final call on game decisions," Konno further explains. "I had only been with the company for two years by then, so everyone on my team either had the same seniority as me or more. This made things more difficult."

"The uncomfortable scraping sound of metallic scissors was very effective in evoking a sense of urgency and the impending danger"

Hifumi Kono

As a result, Kono felt he only had a few people in his corner. "So, I had to ask some people nicely if they could help, and tell others assertively to do as I say. That's how we completed Clock Tower. There was one member of the development team who was particularly defiant. They would openly say 'This game is boring'. "But the moment the game came out and was released to critical acclaim, they started saying 'I worked on this,'" Kono laughs.

And laugh it off he did, because Clock Tower's first release on SNES in 1994 was quite the event indeed. Its success, in fact, encouraged Human Entertainment to create more strange and experimental titles, and also spawned numerous Clock Tower sequels. Even these days, with its old-school graphics and simplistic movement, Clock Tower remains terrifying in its original form. This is because it creates its own terrors through its unusual design, atmosphere and narrative – all drenched in strange visions of Seventies horror.

"The most important thing for me was the stillness – nothing happening, just walking down the hallways in complete silence," explains Kono. "The only sound you hear is the echo of footsteps. In creating those moments of stillness, I think I succeeded in making the appearance of Scissorman and the fear of the sound of his scissors more effective. Mr [Koji] Niikura was in charge of the sound direction, and he really demonstrated his superb skills in this extremely important facet of the game."

Indeed, the sound of Clock Tower contributes hugely to its legendary atmosphere. Its soundtrack is actually pretty stark – mostly permeating with distant wind ambience and jarring footsteps. There is very little music. However, when Clock Tower's urgent, bombastic and sinister theme Don't Cry, Jennifer hits – signalling that the Scissorman has arrived and you must flee – it has all the more impact as a result.

Cutting deep

Among its most notable terrors, series mainstay Scissorman – in-game name Bobby – is among the most well-known. "The part about Scissorman being a child was most strongly influenced by Phenomena," explains Kono. "However, the idea for his characteristic scissors came from the character Cropsy from The Burning [a disfigured maniac holding gardening shears aloft], and The Eroded Scissors from Kazuo Umezu's comic, God's Left Hand, Devil's Right Hand."

"In The Eroded Scissors, there was a scene where scissors burst through the heroine's cheek from the inside of her mouth, and there was this easy-to-imagine, genuine pain about it specifically because it was an everyday item. And that's something that I thought we could convey to players on screen through the medium of video games. Also, the uncomfortable scraping sound of metallic scissors was very effective in evoking a sense of urgency and the impending danger."

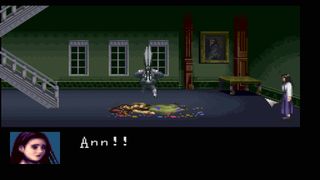

Scissorman's lack of seriousness is part of what's inducted him into the horror villain hall of fame. He creeps on you, steady and repetitive, and if he catches you in his grasp and brutally murders you, he does a little victory dance on your corpse. He's also a constant threat, that can turn up anytime and anywhere. The scene in the enhanced PlayStation port, Clock Tower, where Scissorman is sitting in a rocking chair watching cartoons, is among Kono's favourite scenes of the series.

"I think the idea of a killer who innocently laughs at cartoons coming after you has a much more unsettling fear to it than a murderer who's serious." But more crucial to horror than cheek-splitting antics and little men wielding scissors, is pacing, according to Kono. "It's true for all games, but I think it is especially important for survival horror titles. Those games are fast-paced when you're being chased or fighting monsters, but if they continue without letting up, then the player will grow numb to it," he says. "That then makes the monsters, which should be the focus of their fear, become mere obstacles. To mitigate that as best as possible and keep the monsters terrifying, you should pace things out in waves by periodically having a quiet, slow-paced situation."

He adds that unlike passive media, such as films and television shows, players have a strong degree of free will in video games, adding a level of complexity to solid pacing. However, it's not the only thing to consider when creating captivating survival video games. "Do not rely on the fear of your monster's design," explains Kono. "Simple visual scares are only one pillar of a game. To put it in cooking terms, they are only one ingredient in a dish. So you need to put your heart and soul into how you create an atmosphere as the 'seasoning' that brings those ingredients to life."

He elaborates that the monster designs in Silent Hill are superb on their own, but that the radio is actually one of the scariest aspects of the game. "The radio noise itself creates an ominous sense of foreboding, which is substantial in heightening the atmosphere before monsters appear," he says. He advises budding horror game designers to analyse fear as much as they can. "The word horror can be broken down further into many different genres, each offering its own quality of scares," he continues. "What kind of fear do you want to present? Where does that fear come from? You must always remember that there is no clear, correct answer to these questions."

"For example, a very young child who's frightened will hug their mother. Most of them will face their mother when they do, but some will press their backs up against their mother and face outward," he continues. "Are they afraid of seeing what they fear, or are they more afraid of not being able to see it? Fear is different for each person." Following on from the huge success of Clock Tower and its sequels, Kono, now part of his own Tokyo-based company Nude Maker, is in the process of carefully composing a project he'll be "satisfied with". In particular, Kono would love to start a brand-new horror title.

"However, except for zombies, modern survival horror games have a very difficult time balancing both the size of the market and the increasingly large budgets needed for quality graphics," he concludes. "How we'll solve this, is a major challenge as we continue to move forward."

This feature first appeared in Retro Gamer magazine issue 218. For more excellent features, like the one you've just read, don't forget to subscribe to the print or digital edition at MyFavouriteMagazines.