Intelligent, emotional, and terrifying, Hereditary is near-perfect horror. With a little more restraint, it would have been flawless

Hereditary is one of the cleverest horror films of the decade. If it hadn’t been betrayed by its ending, it would have been perfect...

There’s a point in Hereditary’s first half when Peter, the son of the beleaguered family at the centre of the film’s nightmare, is asked during an English class whether it’s more or less tragic if a flawed protagonist lacks control over their own fate. It’s an interesting philosophical question – for me, the answer is ‘less’, because self-inflicted defeat is always more painful if it could have been avoided – but also a clear commentary on the film’s emerging themes.

(Full spoilers for the movie follow)

Because Hereditary, as its title suggests, is in part a horror film about legacy and the notion of pre-determined fate. It explores this conceit through examinations of parental failings passing on damage from one generation to the next. It explores it literally, through fears of familial predisposition to mental illness. And it also explores it through some bigger, darker, entirely more conspiratorial ideas. As a piece of thematic garnish, used to throw an extra level of discomfort on top of its many layers of uncertainty, Hereditary’s posing of this literary conundrum is a clever and well-considered move. In a film that thrives on the steady tightening of the noose, the side-question of futility is a horribly effective amplifier.

I just wish that Hereditary didn’t ultimately come so close to answering it.

Hereditary is a staggering piece of work. While without question one of the most powerfully crafted, instinctively disturbing pieces of horror made over the last decade, its ability to threaten and intimidate long after the fact – it lingers in the mind like mould in the attic – isn’t simply a product of the bravery and brutality of its imagery and ideas. Hereditary’s real power comes from how indivisibly it blends its horror with real, human trauma.

This clash point between fantastical dread and relatable, human destruction is where Hereditary thrives, its heart beating amid uncanny ambiguity. Is a supernatural plot, instigated long ago by her distant and recently deceased mother, really guiding the path of protagonist Annie and her family, or is Annie unravelling with grief for both parent and – later – her own daughter? Is an unholy terror drawing in, or is Annie just terrified of more Earthly things, and spreading that fear throughout her clan as her psychological state deteriorates? The point is that it doesn’t matter, because whatever the specifics, the emotional truth of the situation is the same. Emotional truth is what drives Hereditary.

A terrifying reality

Regardless of the potential input of ghosts, demons, and shockingly effective séances, the painfully relatable reality of Annie’s collapsing mental state and the many, mutually destructive acts it triggers among the family is the terrifying core of the film. Already struggling to make sense of her feelings toward her coldly detached mother and the psychological damage wrought upon multiple generations of the family by the woman’s behaviour, Annie is, from the start, splintered with self-doubt and justifiable fear as she finds herself pushed into the role of matriarch.

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

Suddenly faced with a magnified sense of responsibility after struggling for control of her own life for her entire life, she quickly and convincingly begins to fray. Her various emotional threads are pulled in multiple directions by a great many questions.

How damaged is she by her mother? Is destructiveness a genetic inevitability in her family, given the tragic fates of her father and brother? How much has she already damaged her own children (we find out later that she once nearly killed them in a sleepwalking trance)? How much of that was she truly responsible for, and how can she navigate those already fractious relationships in the future? And that’s all before the nightmarish death of Charlie, her daughter, in harrowing circumstances that are at once nobody’s fault, while also potentially everybody’s.

The car accident that kills Charlie might be an accident, but it’s also the product of a complex sequence of granular causality, in which, at some point, every member of the family could be fingered for responsibility, should pain turn to rage, and rage spawn spiteful accusation. Which of course it does. While Annie’s mother’s death sets her down a path of detached introspection in which she questions herself and those closest to her in equal measure, Charlie’s death is the grotesque catalyst that sends the whole family down that dark, bloody road together.

From here, Annie’s questions seep through the collective minds of the household like a sticky, black infection. As fears escalate, suspicions (both supernatural and interpersonal) grow, and truly upsetting things happen to people who truly do not deserve them, Hereditary’s real focus remains not on external horror and mystery, but on the emotional and psychological reality of it all. Where other horror films trade on the cheap catharsis of watching winsome heroes defeat some variant of a bad monster (no doubt tangentially representing some societal fear or other), Hereditary stabs straight for the other end of the allegory. It isn’t interested in abstracting the painful parts of the human condition into something tangible that can be safely vanquished. It’s interested in depicting the source.

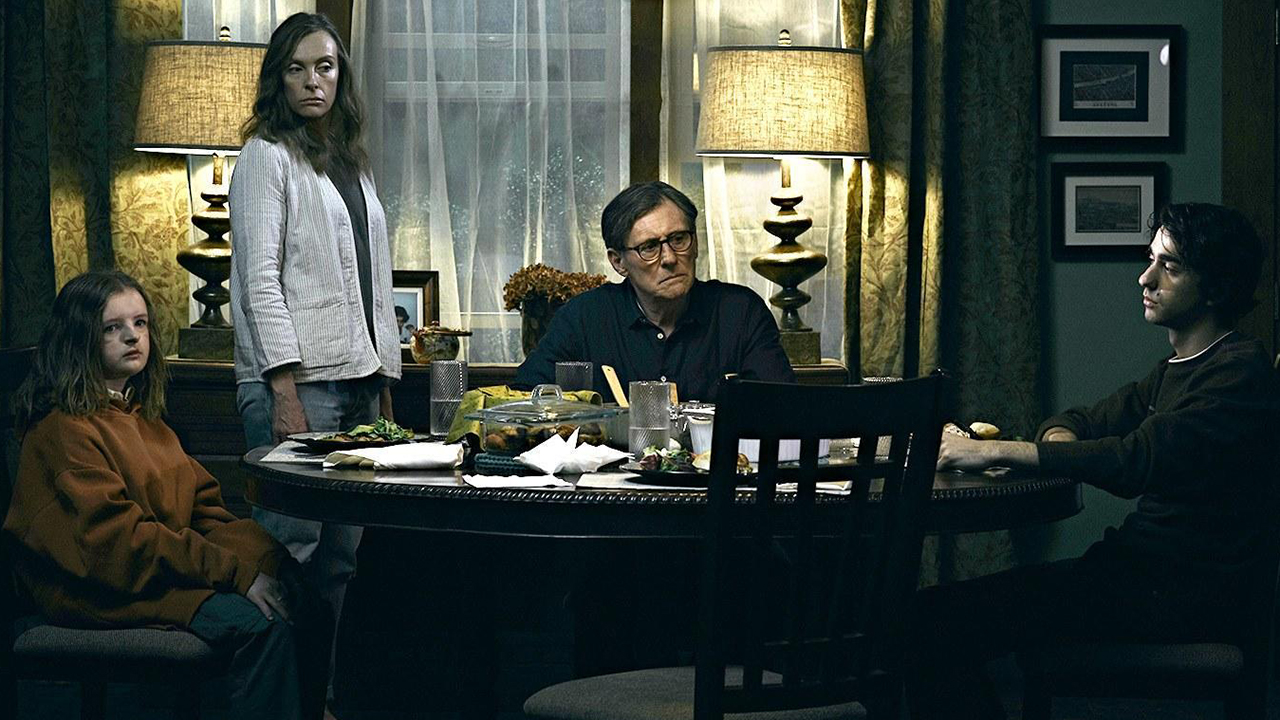

So, as the dread closes in, Annie deteriorates, and her fears, obsessions and manias rush to meet it, we get an agonising depiction of a family torn apart by real horrors. We get an inextricable blend of truth and allegory wrapped around the destructive, sometimes selfish outcomes of depression and grief. We have our faces pushed and held into the point where guilt, despair, and self-recrimination meet frustration, blame, and delusion. For all of Hereditary’s instinctive ability to construct profoundly disturbing imagery and ideas – and truly, it is deeply disturbing; you’ll find no quarter for the casual Friday night horror crowd here - few moments are more upsetting than the point a fraught family dinner almost leads to mutual understanding and reconciliation before sliding painfully (but believably) back into accusation and attack.

So near, and yet so far

That particular scene is possibly the film’s most important tipping point, the crux of its discussion of the inevitability or avoidability of human disaster. A different response from Peter, at the end of his mother’s long-repressed outpouring of grief, of her explanation of all her flawed attempts to make sense of what she’s going through, could have turned things around. If he had taken a little more time to cool down, to warm to the idea of responding to her tirade with tact and understanding, the situation might have been saved. But he says a bad thing, and from that point there is no recovery to be had.

That doesn’t make him the villain of the piece, by any means. It doesn’t turn Hereditary into a contrived morality play, in which Peter ultimately deserves his final fate, terrified out of his wits and forced from his body to be possessed by a King of Hell. Nor does this feed in to some kind of punishment for Peter’s part in Charlie’s death. For all he drove the car she died in, and for all that frantic drive to the hospital might not have been necessary had he kept a closer eye on his sister, this very dinner table tragedy hinges around the very notion that many different factors led to that particular horror.

Rather Peter’s response is just another in the sequence of damaging but understandable actions that sear through Hereditary like a burning match dropped into a box of firecrackers.

At its most effective, Hereditary is a potent psychological drama that uses the language of horror cinema to relate the emotional heart of its events. Having introduced a supernatural tension to heighten the chaos of grief, self-doubt, and depression, Hereditary then uses a punishing realisation of is genre to explore those latter, more grounded horrors from the inside. To make normality unreal and terrifying, because at such times it is.

For the longest time, nothing undeniably inexplicable happens, except occasionally from Annie’s point-of-view. Things feel deeply wrong, of course, because they should. Because at such times they do. The lifelike, dolls-house dioramas that Annie crafts – partly as work, partly as therapy, partly as a means of detached control - swiftly become a disturbingly ambiguous visual signature. Uncomfortably perfect symmetry, jarring breakdowns in the depiction of time, and matter-of-fact, plain-sight dread deliver the relentless follow-up blows. It all nails down the sense of living distant and disconnected within a rolling fever dream.

Giving up the ghost

So it’s somewhat frustrating when Hereditary shifts gear toward its end. After leaving that question of the flawed hero’s self-made fate dangling over a believably flawed family for so long, after allowing us to invest in how they might or might not save themselves and each other from an external threat that may or may not exist, Hereditary starts to deliver concrete answers and explanations. Explanations which, alas, derail much of the discussion. It stops letting the human truth of its characters’ plight dictate its discourse. It removes the ambiguity that lets us ponder the weight of our personal agency in the destruction we cause for ourselves and each other.

‘Yeah’, it says. ‘A demon did it all. There’s a cult too. Annie’s mother ran it. They orchestrated Charlie’s death as part of a conspiracy to conjure infernal royalty upon the Earth, and Annie’s grief was manufactured and manipulated every step of the way to the same purpose. These people had no chance. Not from the first moment. All of their pain was engineered by an outside entity, and driven from the start to ruin them. And this shit started years ago’

As a hammer-blunt, and rather nihilistic, metaphor for notions of predestination and the resonance of previous generations’ transgressions, it’s an effective one. But it makes the final reel of Hereditary far less interesting. And that’s a shame. Because while Hereditary maintains all-time great quality to its end in terms of pure horror – it delivers sickening fear until its last moments, and certainly some of its most lasting images occur within the final minutes – as it runs to its finale, the film is no longer about what it once was.

Even ignoring the potential problematic handwaving of mental illness as supernatural symptom, Hereditary’s final revelations and resolutions simply detract from its original meaning and might. Initially, and for most of its running time, Hereditary is an incredibly good, deeply human horror film about the devastation we can wreak from a position of pain. It’s a harrowingly real depiction of how desperation, sadness, and isolation can tear us from the people who can help, and how self-assertion can turn into selfishness when we try to do too much, unchecked and alone. It ends as ‘just’ an incredibly good horror film about demons and a cult conspiracy sealing the fate of a family three generations before the opening credits begin. It’s still a hot, angry, and aggressively disturbing film, but its horrors carry less weight.

When you retroactively remove agency, when flawed characters really do have no control, their flaws ultimately no longer matter. And, in turn, neither do their actions. When you remove autonomy from a character, you also remove responsibility. As such, it’s rather a shame that a film so intelligently, innovatively terrifying as Hereditary – so imposing as a piece of horror, and so unusually, profoundly, thoughtfully upsetting – eventually gives responsibility for its conclusion away.