"Fallout was one of the first games that really shocked:" Our first glimpse of Fallout 3 showed how hard Bethesda worked to inherit and maintain an RPG legacy

From the Vault | Bethesda's Todd Howard and Istvan Pely weigh in on our first Fallout 3 preview in Edge Magazine, 2007

In GamesRadar+'s From the Vault series, we're bringing you compelling exclusives pulled from our sister magazines' back catalogues to give you a taste of how we were discussing your favorite Fallout games back when they were first introduced.

Today, we've unearthed Edge's preview experience with Fallout 3 from 2007 to bring you some initial impressions of Bethesda's groundbreaking take on the RPG universe before it blew up (literally).

Fallout 3 preview (Edge 179, 2007)

A matter of jubilation to some, trepidation to others, Bethesda Softworks' acquisition of the violent roleplaying franchise Fallout back in 2004 has caused contention amongst its legions of avid fans, filling their still-thriving web communities with vitriol, fervour and wild speculation in equal parts.

Finally, the fruits of Bethesda's labours have come to light, and although those dogmatically opposed to the company's involvement with their beloved series will probably never be appeased, more reasonable fans should find much to reassure them that Bethesda has diligently resurrected the spirit of Fallout – and, further, they should be impressed by how the developer has stayed so faithful to the past while contributing some considerable innovations.

Brave nuclear world

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine #179. For more in-depth features and interviews on classic games delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge or buy an issue!

Though easy to mock, it's also hard to begrudge the fans' preciousness about Fallout. It's a series that justifies its devoted following; Black Isle Studios, now defunct, created a world that placed startlingly few limitations on your interaction with it and yet, miraculously, somehow delivered depth and humour in each of your decisions.

Driven by a unique art style, Fallout was set in an ingeniously realised vision of a post-apocalyptic America as it might have been imagined in the 1950s – an irradiated wasteland juxtaposed with the can-do jollity of the Cold War era's civil protection booklets; a World of Tomorrow optimism wittily undercut by the horror of survival in what has become a desolate and brutal world. Fallout 3, in this respect, is faithful to its predecessors.

"We've carried through all the major themes and design decisions from the previous games," says lead artist Istvan Pely. "Like, for example, the combination of futuristic technology with a 1950s vibe; every car is nuclear powered, but there's a strong retro quality to them." Bethesda seems to have fully understood the appeal of that world's grim humor, and naturally the iconic mascot of the series, Vault Boy, returns to prominence.

He is a parody of the false optimism that typified the US government's thermonuclear war survival handbooks of the 1940s and '50s – winking and smiling while wrapping the irradiated corpse of a close family member in polythene. In the world of Fallout he is the cartoon figure of encouragement adorning the instructional brochures that accompany the lucky few down to the Vaults – self-sustaining communities sunk deep into the earth, beyond the reach of radiation.

"We've definitely come to love Vault Boy," says Todd Howard, the game's executive producer. "The whole world's blown up and you get Vault Boy giving the thumbs-up. I think there's a big chuckle factor in that. The humor in the game is something we talked about; how we could use it without being silly. A lot of Fallout's humour is very ironic."

And it's Fallout, in preference to Fallout 2, that has been the model for the new game – with Howard asserting that the latter's humor erred towards the crass, bombarding the player with edgy content in a way that sometimes felt forced. "Fallout 3 is set 30 years after the events of Fallout 2, but the first Fallout is our tone setting for the game," says Howard. "As far as Fallout: Tactics and Brotherhood Of Steel go, we tend to ignore them in much the same way I prefer to ignore Alien 3 and 4."

Whilst Bethesda has drawn a great deal from the first two games of the series, it's been necessary to expand upon that vision. "We stayed very true to the flavour of the original game, but where there were blanks we filled them in with our own details and desires – just by extrapolating," says Pely.

"The original game, whilst innovative for its time, only had a few pixels dedicated to any one asset, so when you're fleshing that out for high definition, there's a lot of opportunity to put our own twist on it. With the technology now we can go to such greater levels of detail and a higher level of realism – I wouldn't say photorealistic – more like a hyper-realistic density. It gives us a lot of freedom to interpret what the world would look like."

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Blast zone

When you sit down and play Fallout 3, the character system is 100 per cent different from Oblivion's

Todd Howard

However, where Bethesda has dared to go further than Fallout 3's predecessors, it has nonetheless stayed true to the series' tone.

As you venture beyond the cloying safety of the vault and explore the blasted wasteland, your Pip-Boy 3000, an arm-mounted PDA, picks up radio signals. Occasionally you'll hear odd bursts of chatter which will give you information or tip you off to potential missions, but by and large you'll hear the local radio stations' selection of '40s music – 20 songs have been licensed from that era.

Accompanying your violent escapades in a desolate, brutalised landscape with the lulling sounds of jazz is a juxtaposition that evokes the spirit of those earlier games perfectly.

The brutalized landscape in question, however, is not precisely as it was in previous titles – the new installment sees the setting shift from one side of the US to the other: "It's still a wasteland," says Pely. "But it's not a west USA desert, it's how the wasteland would look on the east coast and the Washington DC urban area."

The environment has been generated with great fidelity – not to the extent that every street of Washington DC is recreated; Howard is keen that the design serves the gameplay rather than function as an in-joke for people familiar with the city.

"With Washington DC, there are buildings which aren't in the game and we've added sci-fi touches, but we want the world to feel very, very real," he says. "Even though it's this comic-book pulpy thing we are really anal about this. What would the wasteland around Washington DC look like? How would people live and survive here? What would people wear to live underground?"

This vision has no doubt been informed by the concept art of the exceptionally talented Craig Mullins, whose bleak vistas were recently seen as teaser artwork in the build-up to the game's unveiling, but actually created much earlier, during pre-production.

"It was some of the first art we had done for the game," says Pely. "Its primary purpose was for us, to inspire us, and help us find a direction for the game. There's a shot of the Capitol Building with the dome busted – this is our icon, this is what we're going for, this is the kind of flavor we're going to give to our environments. Hopefully the game itself reflects the same level of destruction, detail and quality.

Even the color palettes follow through. "We had a lengthy pre-production, so we spent a lot of time drawing and designing things. In-house we have our own brilliant and super-fast concept artist, Adam Adamowicz, who goes through hundreds and hundreds of drawings. When we asked him to design the Pip-Boy, I think he went through something like 20 or 30 iterations until it was perfect."

Cross contamination

You don't really curse the decisions you made ten hours ago when you play Oblivion, but with Fallout you get that every hour.

Todd Howard

Of course, regardless of Bethesda's intense efforts in recreating the look and feel of Fallout, there will always be those rabid detractors who claim that it is no more than Oblivion with guns and giant mutant scorpions.

The nature of both games inevitably means that there is considerable crossover in their design ethos. "Fallout 1 was the kind of game we really loved," says Howard. "It's more or less a wide-open game. It's what we try to do in our games. If you look at Oblivion versus Fallout, the big things they do – allowing you to make this character and go into a world and do what you want – they're the same. We're not going to change that. It works well.

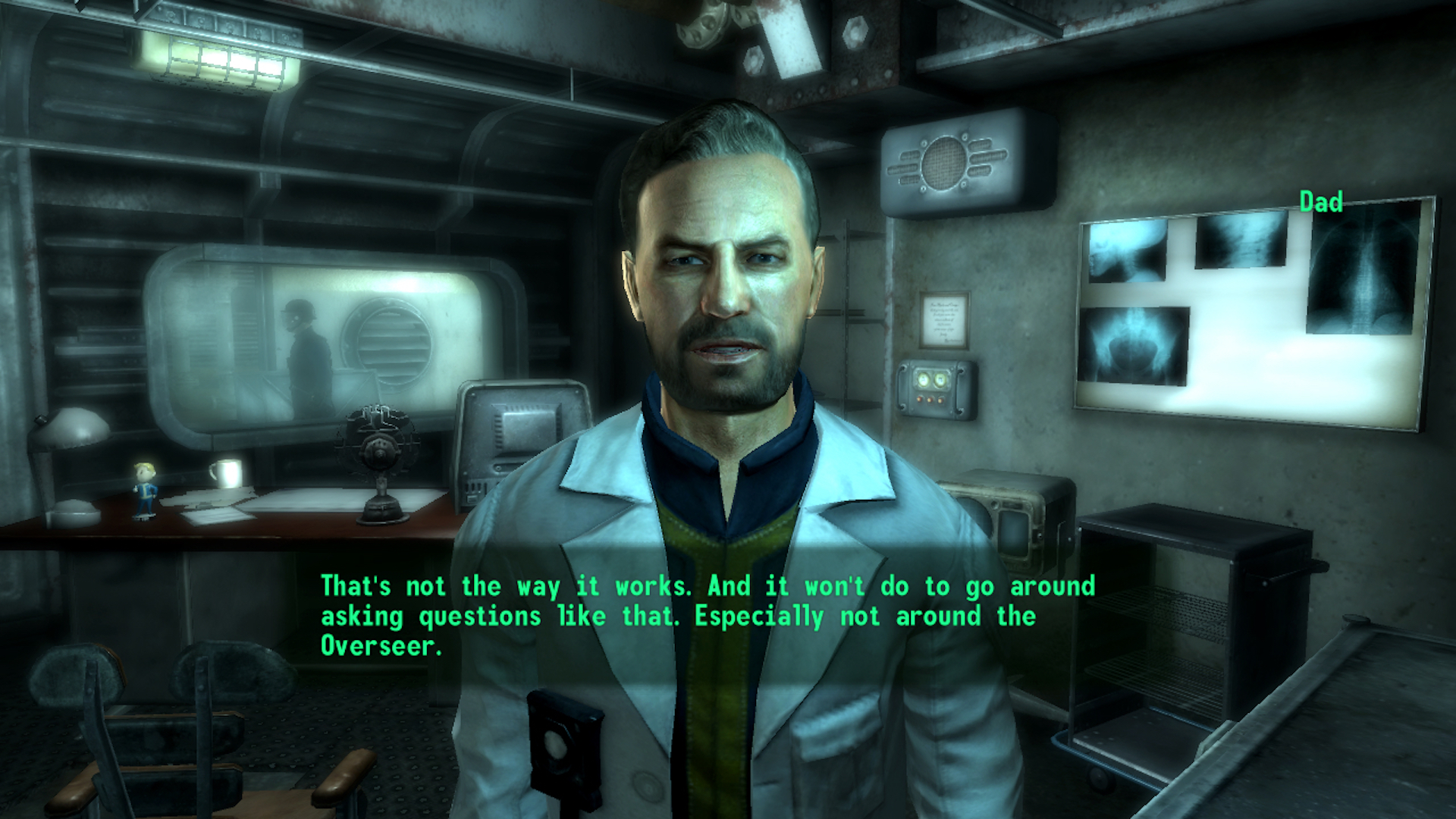

"But when you sit down and play Fallout 3, the character system is 100 per cent different from Oblivion's; how you level up, how your skills interact, they're both very, very different. The game has a very different flow to Oblivion."

In fact, the comparatively smaller scale of Fallout 3 determines that it will necessarily feel significantly different. Though it may be no more linear than Oblivion, its world is smaller, its people fewer, its depiction more focused and intently crafted.

From the art perspective, this means that there's no procedural generation of terrain, as Pely explains: "It's all done by hand. Throughout the whole world there won't be a square foot that won't be touched by an artist. But although Fallout 3 is a lot denser than Oblivion, its world is still pretty big. It doesn't feel like any less work than the previous game, that's for sure. But though it's a huge undertaking, from my perspective, I find it liberating because we can spend that much more time polishing every little detail."

Such narrowing of focus also helps to mitigate many of Oblivion's failings. In a world as huge as Cyrodiil, it was inevitable that much of it would feel somewhat bland – a criticism directed particularly at its characters and dialogue.

"I think oftentimes the scale of our Elder Scrolls stuff gets in its way," says Howard. "Where people compare our content to something they see in another game that is smaller and more focused. But a lot of the problems you get having 1,000 to 2,000 characters go away in a smaller game."

Whereas Oblivion's entire populace was voiced by a tiny cadre of actors, Fallout 3 uses 30 to 40 actors for the few hundred characters that populate its world. "We really don't have very much of that generic dialogue," says Howard. "In Oblivion you're writing for a thousand people – so every line is very flat, you don't add a lot of character to it because you don't know which character is going to say it. In Fallout 3, almost every line is specific for a character and so you can bring in a voice actor and say, this is who you're playing, this is their attitude, this is why you're responding in this way. It makes a world of difference."

Oblivion's randomly generated dialogue between NPCs was also the source of some derision – often producing garbled and stilted conversations about mudcrabs that made little sense in the context of a demonic invasion. Emil Pagliarulo, the man responsible for Oblivion's justly lauded Dark Brotherhood section, is keen to emphasize how the smaller number of characters has allowed for a greater personalisation in this respect.

"We've done a much better job of making the dialogue between characters more believable," Pagliarulo says. "So for example the sheriff has a son, and if you were to follow him when he goes home and listen to him talk to his son, the dialogue he has is specifically tailored to that relationship."

Something in the water

Violence done well is just fucking hilarious.

Todd Howard

Probably the most significant difference in scale between Oblivion and Fallout 3 is not in the size of its world, or the number of characters in it, but in the simple fact that the game actually ends.

"If you follow the main quest there's going to be a point where it's pretty clear that this is the end of the game," says Howard. "The way we're doing it, it needs to end, and it feels very good. But it's still a game where you can wander the wasteland and kill creatures, and find holes and buildings to go in and try to level up and get power and go to cities and do all of those things.

"But because you can't pick all of the character traits on one playthrough you might start over – you might play it for 20 hours and then try a different character, but you'll probably have done a few of the main quests."

The team estimates that the average time to completion will be about 40 hours, with half of that time spent on the main quest itself. The repercussions of this design decision are huge and possibly the greatest reason for excitement about the game – Fallout 3 demands replay, not simply because the character you play is superficially different in its capabilities, but because the game offers a plethora of choices that significantly alter the game experience each time.

"A lot of people's experiences in Oblivion are different only in the order they do things, not in their actual nature," says Howard. "You are the everyman in Oblivion," agrees Pagliarulo. "You can do everything in the world. It's very different in Fallout because of the choices you make. Depending on your actions, certain paths are closed to you, so you can't cover everything the way Oblivion does in one session."

That Bethesda is accommodating dramatically different replays of the game is confirmed by the fact that Fallout 3 will feature between nine and 12 possible endings – some of which will be rooted in decisions significantly earlier in the game.

"When we did the main quests in Elder Scrolls, we knew that you could keep playing," says Howard. "There were certain things we couldn't do with the endings because there might have been a lot that was still going on – so maybe the endings got nerfed a little bit. With Fallout we wanted to have the consequences of your decisions have a lot more balls to them. You don't really curse the decisions you made ten hours ago when you play Oblivion, but with Fallout you get that every hour."

An example of such a decision with "a lot more balls" would be the detonation of an entire town. Fresh out of the Vault, your character stumbles upon Megaton, a settlement clustered in the crater of an unexploded nuke, its inhabitants having grown to revere the bomb as a sacred object.

"It is no less significant a place than the cities of Oblivion – and yet, should you choose to accept a mission from a shady character you meet in one of the bars, you can blow the entire place from the face of the earth, attaching an explosive to the nuke's underbelly and then activating it from a safe distance.

Choose your own misadventure

...as rich in choice and imagination as its wasteland is desolate.

The branching paths of any RPG are always rooted in the character creation system, and Fallout 3 has one that, while remaining true to the trait selection of previous games, should prove to be more organic.

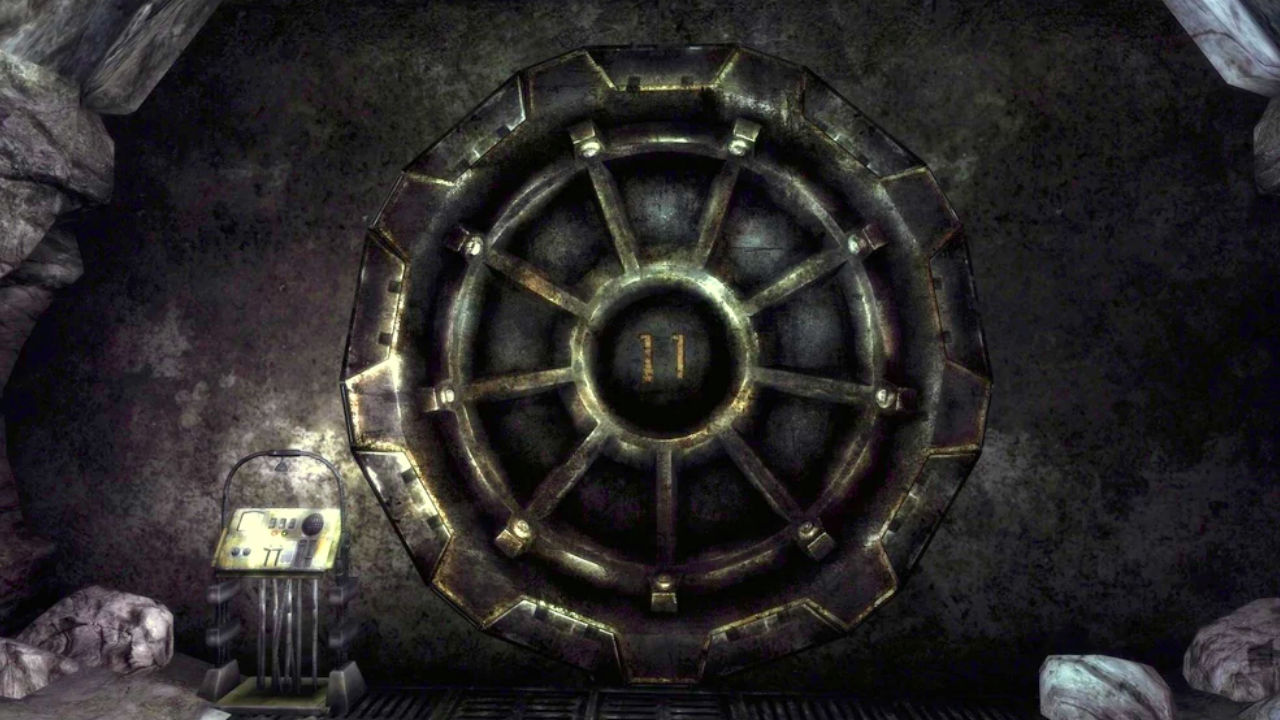

Spread across the first hour of the game, your character creation is integrated into your early life in the cloistered confines of Vault 101, flashing through periods between birth and adulthood. The first thing you do as a player is to pick your appearance, and immediately after your troublesome birth your father removes his mask to reveal that he shares many of those same features.

At a later point, he gives you a children's book, entitled 'You're Special!' via which you balance your seven primary attributes (conforming to the SPECIAL system familiar to fans of the series), and later still you are subjected to the Generalised Occupational Aptitude Test, defining your skill-set further.

Traits, the small selection of extreme character quirks that lend your creation greater idiosyncrasy will return – and it was strongly suggested that these would include the popular Bloody Mess trait, ensuring that your enemies expire in the most gruesome manner possible.

Bethesda no doubt has other grisly tricks up its sleeve, although Howard chose to remain coy about the meaning of one loading screen, which detailed statistics on the number of corpses that the player had eaten. "People forget that Fallout was one of the first games that really shocked," says Howard. "It was like a dip switch for violence. And, let's all just own up to it, violence done well is just fucking hilarious."

Certainly this is a sentiment apparent in the selection of Fallout 3's arsenal, which features, among other comic-book horrors, a hand-held nuclear rocket launcher.

"One cool feature in the game is you can make your own weapons," says Howard, explaining how you can deconstruct existing weapons and recombine their parts to create something new. He offers examples: a home-made flak cannon, which shoots rocks and other useless junk, and a shrapnel bomb consisting of a lunchbox filled with explosives and bottle-tops.

The flipside to the modifiable weapons is that each component degrades, affecting the stats of the weapon: its spread, reliability and rate of fire all change over time, whilst your own skills determine the steadiness of your aim and control of the weapon.

It makes combat a more considered process than in most first-person shooters, complemented by Bethesda's ingenious implementation of an optional feature, known as VATS, which allows the player to switch between visceral gunplay and turn-based tactics at their leisure (see 'Assisted aggression'). Such a tactical combat system offers a fundamental departure from the style of play made familiar to us by Oblivion, and underscores the fact that Bethesda is quite assuredly making a Fallout game, rather than a sci-fi Elder Scrolls.

Yet the brilliant touch, one which makes it apparent that Bethesda and the Fallout franchise deserve one another, is that the use of it comes down to player choice. It is this, as much as the Vault Boy or the post-apocalyptic wilderness, which defines Fallout, and Bethesda's cognisance of Oblivion's sometimes unwieldy scale suggests that the team will deliver a game as rich in choice and imagination as its wasteland is desolate.

See where Fallout 3 ranks on our list of the best Fallout games , 17 years since launch

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.