Feathers, orbs, and shame: how modern collectibles have failed us (and how they can do better)

Things are getting better... but slowly

Collectibles and video games have a long, shared history, one that stretches back to the earliest days of the arcade. In those ancient days of antiquity (way back in the 1980s), players huddled in the dim glow of garish games cabinets, guiding a little yellow sector named Pac-Man as he frantically gobbled pellets and fruit in his neon, Cretan labyrinth. As games have continued to expand and diversify, so too has the way collectibles are implemented, for better in some cases but for worse in many.

In the early days, the appeal of collectibles was self-evident. You got the fruit, grabbed the treasure, ate the flies because it earned you points; points that earned you and your three letter avatar a slot on the leaderboards and, by proxy, bragging rights. While score chasing has fallen somewhat out of favor in the last couple of decades, in the arcade era points were king, and collectibles were the power behind the throne.

Read more: Find all the actually quite cool Papyrus Scrolls in Assassin's Creed Origins

For a long time, collectibles evolved naturally alongside game design, with the golden coins and rings of the 8- and 16-bit eras adding not just points but precious 1-ups as games abandoned the arcades and followed players home. With the explosion of 3D and the vast, immersive environments this startling new technology offered, designers used collectibles to steer us to the hidden nooks and crannies tucked away in their worlds.

A checkered past

To my mind, Grand Theft Auto 3 marks the beginning of the modern age of collectibles, and it began with such promise - collect ten of the 100 hidden packages and you're rewarded with a weapon that would always spawn at your home base. They're hidden away in dark corners and secret areas, incentivizing exploration, but you don't need to vacuum up all 100 of them before you get something meaningful in exchange. And Rockstar found a sweet spot in terms of density, neither so thick you're always tripping over them nor so sparse they're frustrating to track down (each of GTA 3's 3.5 square miles hosted an average of around 28.5 packages).

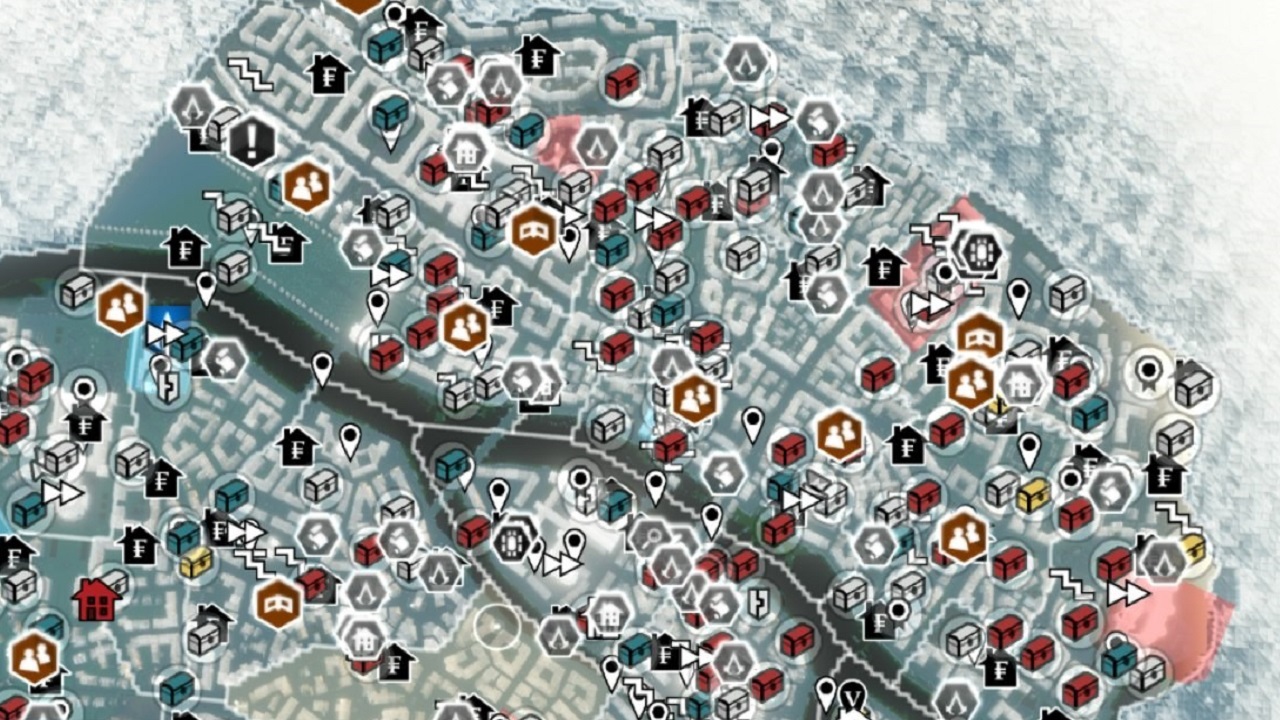

But at some point we lost the thread. There was embarrassing glut matched with a sense of almost Sisyphean futility, as in the original Assassin's Creed which was hideously overstuffed with 420 flags as well as pseudo-collectibles in the form of 60 Templar targets to track and kill; collectibles by way of homicide. Gathering them all yielded no reward of any kind, other than a sickly sense of achievement at satisfying certain dark, compulsive tendencies, and fewer than 10% of Xbox 360 players who picked up AC have done so. Undeterred, the sad tradition continued in later entries, evidenced by Assassin Creed Brotherhood's baffling diversity of collectible detritus (210 treasure chests,101 Borgia flags, ten feathers, ten Clusters, ten Glyphs, five Artifacts, and a partridge in a pear tree) and failure to reward players for gathering them.

Read more: Find all the really useful hint art in Super Mario Odyssey

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

While Ubisoft may be one of the most egregious they are hardly the only offender. Though the original Crackdown made tracking down its agility and hidden orbs worthwhile for the power boost they provided, it also jammed its map with a staggering 800 of them. Like it's spiritual successor Saint's Row 4 and its 1,255 power clusters, Crackdown's orbs crowd practically every surface in the game and look less like a fun and meaningful collectible and more like litter. With only 9% of players finding every agility orb and an even slighter 6% hunting down all of the hidden variety, the return on investment for the time and resources it took to spray them across the map hardly seems worth it.

While some recent games have reformed themselves around players' fatigue with collectibles (like the latest Assassin's Creed, Origins, which has drastically curtailed the flood of meaningless pickups), we still get examples like Wolfenstein 2 with sad regularity, a wonderful game but one overflowing with 200 pieces of useless flotsom to shovel into your virtual goodies bag.

Too much of a good thing

The issue isn't just with collectibles that don't provide any substantial reward, or with games that jam a ridiculous number of them into their worlds in a way that's distracting and detrimental. It's collectibles that don't fit the game world, that either don't match the fiction and environment or are so wildly out of place they break immersion with no proportional payoff (the 100 thermoses randomly strewn around Alan Wake jump immediately to mind).

But the largest and most intrusive sin that modern collectibles commit is the way they reduce games, an outlet for escape and entertainment, into dreary busywork. This is exacerbated by the bizarre design cycle to which collectibles have been subjected. When they began being tied to important in-game systems or Trophies / Achievements, players complained if they were too well hidden, which led to devs marking them out with icons or selling in-game maps that showed their location. While this was a convenience for obsessive gamers looking for that precious 100% completion, it also defeats one of the key original purposes of the modern collectibles: to get players to explore a world and seek out the far flung corners they might not otherwise encounter.

Read more: All the completely useless hidden crate collectables in Star Wars Battlefront 2

The icon system reduces collectibles to busywork, to a checklist of menial labor, exactly the sort of thing we come to video games to escape. Instead of engendering a sense of exploration and discovery, this creaking, banal apparatus makes finding collectibles a process akin to completing tedious paperwork. Assigning rewards to collectibles actually exaggerates this problem, making all this checklist busywork semi-mandatory, an unfortunate, odious means to a desirable end.

Collectibles done well are little hidden gems that add something to a story, either through environmental storytelling (like the better Tragic Endings from the Dead Rising series, where you see the story of a survivor's desperate last moments in the harrowing aftermath) or through explicit exposition, like audio logs. They should be rare, meaningful, and never mandatory, missable in the positive sense in that there's absolutely no penalty for overlooking them. And yes, they should be hidden; concealing them is part of what makes them interesting and important in the first place, and for anyone desperate to quickly and effortlessly hunt them down, the internet will provide. Remembering why we call them collectibles in the first place, because they're beautiful, rare, an artifact to be treasured, is the first step to reclaiming their value.

Alan Bradley was once a Hardware Writer for GamesRadar and PC Gamer, specialising in PC hardware. But, Alan is now a freelance journalist. He has bylines at Rolling Stone, Gamasutra, Variety, and more.