Doppelgangers in games are almost always horrifying – we asked an expert why

Interview | I asked a psychologist why doppelgangers in games are so bloody terrifying

I had a moment while playing The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom the other night. Call it a moment, a panic, an irrational instance of sheer, white-hot dread that caused me to drop my Switch console into my lap. I was scared. And while I'd love to tell you I was staring down a fight with King Gleeok or Queen Gibdo when it happened, it was something far more innocuous. Like really innocuous. Like, Link's blooming shadow.

That's right, while trekking across the luscious greens of the Great Plateau, the setting sun split the trees, and cast Link's shadow a little longer than I expected. As the darkness stretched behind the plucky protagonist's heels, for the briefest of seconds, I thought of Dark Link. And my stomach sank.

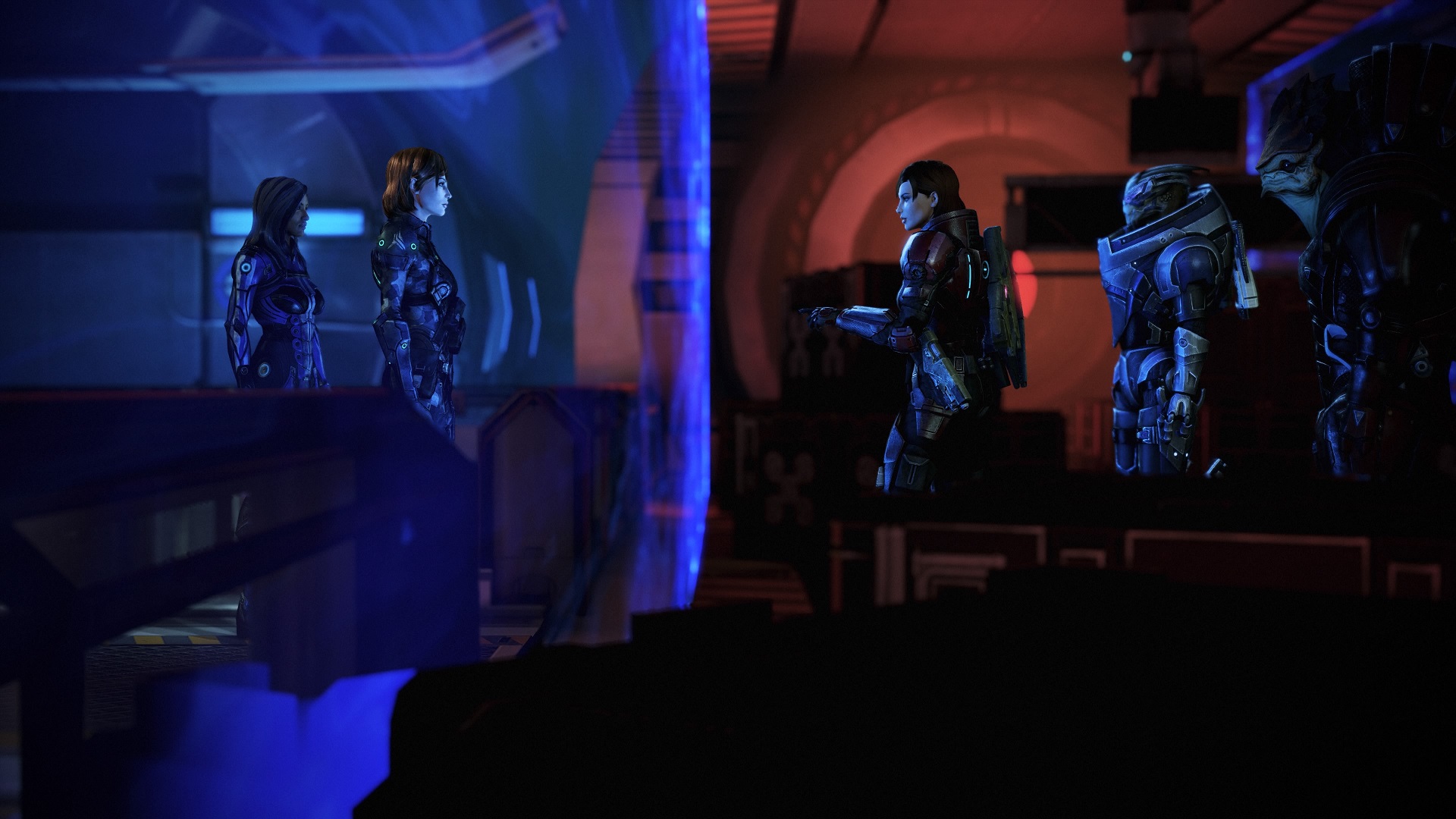

Dark Link, Shadow Link, and Link's Shadow are three mysterious entities that exist in the overarching Legend of Zelda universe, and are in essence mirror images of the series hero. When I first played Ocarina of Time on the N64 at launch in 1998, I found Dark Link to be really unsettling, and have always found doppelgangers in games terrifying. From the first doppelganger puzzle in the first Tomb Raider, to Jeanne in Bayonetta, Evil Shepard in Mass Effect 3, Shadow in Sonic the Hedgehog, Wario (and Waluigi) in Super Mario Bros, Dark Samus in Metroid Prime, and Ditto in Pokemon to name just some that come to mind - carbon copies that err on the side of evil are pretty awful.

My question is: why do we find doppelgangers in games so scary? "Perhaps this fear of the doppelganger villain in video gaming stems from humans' unconscious awareness of their shadow self," explains professor Michele K. Lewis, Ph.D., a professor of Psychological Sciences at the Winston-Salem State University.

Me, myself and I

Professor Lewis suggests that our fear of doppelgangers could be relevant to the basic, primordial terror tied to survival that we share as human beings. In the contemporary world, she says, those fears extend to everything from deep fakes to artificial intelligence taking over our lives, and so social learning from the world around us could factor into our fear of the familiar.

She adds: "Dr James Hollis wrote 'Why Good People Do Bad Things: Understanding Our Darker Selves', and [within that] he suggests that humans have seemingly unexplainable behaviors that are manifestations of The Shadow; which psychoanalytic psychologist, Carl Jung, labeled the 'shadow self' to describe the things people repress or do not like to acknowledge."

Which, to be fair, could be on the money. Despite generally fighting for good in our favorite games, we're often made to engage in a lot of questionable shit along the way – not least murder – therefore the thought of feeling uncomfortable when someone or something holds a mirror to our actions sounds pretty plausible.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

"Rogers believed persons are healthier when there is great consistency between our ideal self and actual self. It likely makes gamers feel really good to create, see, or manipulate an avatar or doppelganger as their heroic ally or ideal self."

Michele K. Lewis, Ph.D.

Part of GTA Online's Halloween event last year involved a doppelganger of your customized avatar appearing at random around the map (whose presence is revealed by a spine-tingling off-key piano chord), dressed in the exact same clothes, with the exact same likeness. After staring you out momentarily upon arrival, the carbon copy would aggressively pursue – and even typing that out several months later is making the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end.

I think we can agree that evil doppelgangers in games are terrifying. But what about when our mirror images are a force for good? Admittedly, I can't think of many times where this is the case, but I will cop to the fact that I'd be absolutely lost without my Mimic Tear Spirit Ashes in Elden Ring – a carbon copy of your Tarnished avatar, from stats to armor sets, weapons, and equipped magic spells. Seriously, there's no way I'd have gotten past the penultimate boss battle with Radagon of the Golden Order without my trusted shadow spirit.

Are there any obvious psychological, un-gamified reasons why a doppelganger portrayed as an ally can be such a huge source of inspiration?

"Yes," says professor Lewis. "[In Humanistic Theory] Carl Rogers divided the self into two categories: the ideal self and the real self. The ideal self is the person that you would like to be; the real self is the person you actually are."

"Rogers believed persons are healthier when there is great consistency between our ideal self and actual self. It likely makes gamers feel really good to create, see, or manipulate an avatar or doppelganger as their heroic ally or ideal self. The use of an ideal self in gaming isn't necessarily cause for alarm, unless a person's ideal self obsession is highly inconsistent with their problematic actual self."

This might be why I, and I'm sure many of you, have become so obsessed with using Mimic Tear at every turn throughout your time fighting Elden Ring's toughest baddies. Well, that and the fact your Mimic Tear is an absolute tank that takes loads of damage and lets you get the drop on your fiercest enemies from behind. But I'm guessing that's not the official stance of the American Psychological Association on human perception of doppelgangers.

Looking for more unsettling adventures? Check out our pick of the best horror games.

Joe Donnelly is a sports editor from Glasgow and former features editor at GamesRadar+. A mental health advocate, Joe has written about video games and mental health for The Guardian, New Statesman, VICE, PC Gamer and many more, and believes the interactive nature of video games makes them uniquely placed to educate and inform. His book Checkpoint considers the complex intersections of video games and mental health, and was shortlisted for Scotland's National Book of the Year for non-fiction in 2021. As familiar with the streets of Los Santos as he is the west of Scotland, Joe can often be found living his best and worst lives in GTA Online and its PC role-playing scene.