Darwin Project is a game hungry for viewers as much as it is players, but can this unique take on battle royale actually work?

Is courting streamers a viable tactic in 2020? The success of Darwin Project depends on it.

This feature first appeared in Edge Magazine. If you want more great long-form games journalism like this every month, delivered straight to your doorstop or your inbox, why not subscribe to Edge here.

Darwin Project is, understandably, extremely motivated to ensure its own survival in a hostile environment – not a wintry deathmatch arena but the overcrowded battle-royale market, which is essentially the same except you're hoarding players rather than wood – and so developer Scavengers Studio is pursuing the most obvious path available here in the bleak future of 2020: courting streamers.

It makes sense for a game that is a hybrid of two genres beloved by online content creators, the perfect Let's Play fodder of survival games, and the battle royale, undisputed king of streaming. But finding that audience is a gamble, and Scavengers Studio isn't about to take a chance on this happening of its own accord. Right on the homescreen, there's an enormous button inviting you to link up your Twitch account – sorry, Mixer – for an interactive viewing experience. Spectators can influence the Directors' actions by voting for which zone to close, or which player to help out with a boost of heat.

Smile, you're on camera

This kind of thing could feel opportunistic, but it entwines nicely with the rest of the game. Darwin Project presents itself as a dystopian reality TV show, another cue taken from The Hunger Games, so spectating and voting is all thematically appropriate. And its combat, probably not by accident, is very well suited to spectating. It isn't especially complex, but the relatively primitive weapons mean combatants – for the most part – need to be in close proximity to one another, sharing a screen as they trade blows, and if the Director isn't watching that corner of the map, fights generally go on long enough for them to rush over and take a look.

But most of all, playing Director is simply a lot of fun, and doing it without an audience feels like creepy voyeurism. Not just because it gives you access to a load of fun toys, from a sunny beachwear mode to the nuclear option – having your finger on the big red button is disconcertingly thrilling – but because it's a completely different type of challenge.

We try to build a clear narrative for our mighty viewership of three by cutting between players as they pursue one another, or watching likely choke points. We even attempt the occasional fancy camera move. Not with great success, but you can see how someone more nimble with these tools could craft an entertaining ten-minute package.

"It's rare, and joyous, to see a game actually improved by shamelessly playing to the crowd"

We play a few rounds with an experienced shoutcaster and – after getting past our natural British wariness of a loud and energetically complimentary stranger – it is a charming experience. With the exception of a megaphone broadcast ability on a cooldown timer, the Director is locked into the same proximity-chat limits as the competitors, and so experiencing it as a player is like being at a party where the host is constantly diving in and out of conversations. It's easy to imagine how this could turn nasty, though – out in the wild, we witness one cheery Director facing a slightly hostile crowd – and the ability to mute and report players isn't always enough of an antidote.

The early-access version of the game included an option to tip your Director with a few experience points, marking their playstyle in the process – were they a careful puppet master, a commentator calling every play, or just a devotee of nukes-and-beachwear chaos?

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

This is sadly absent from the launch version, but it was a good way of encouraging players to not only sit in the Director's chair but to take it seriously, and suggest ways the role could be approached. But the real incentive is going to be external: the knowledge that other people are watching, armed with the all- powerful sanctions of cheers and subs. As with so much of Darwin Project, the success of these features will depend on the growth of its playerbase – but it's rare, and joyous, to see a game actually improved by shamelessly playing to the crowd.

Subscribe to Edge Magazine for only $9 for three digital issues and show your support for long-form game journalism

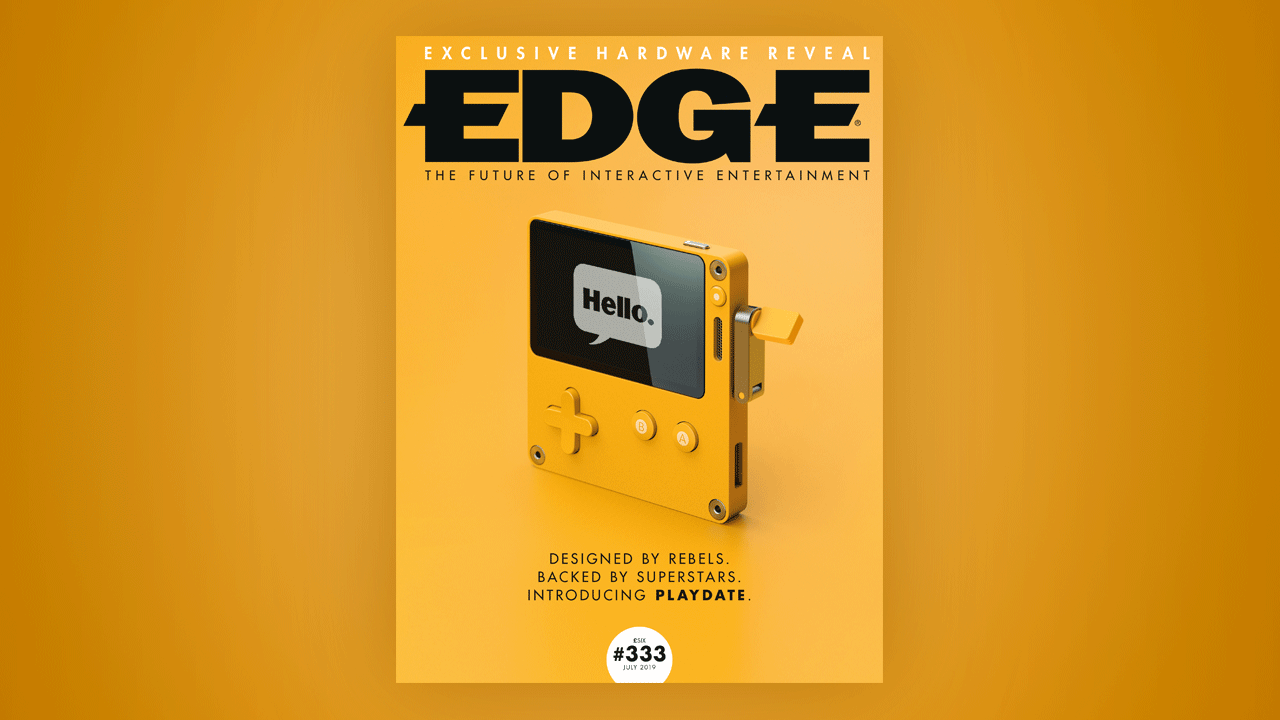

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.