Why virtual reality makes sense for Half-Life: Alyx

Closely absorbing you in a detailed, manipulable world is core to the Half-Life experience

Half-Life’s introductory tram ride is a bit of a gaming landmark. Instead of a cutscene, info-dump, or Star Wars-esque opening crawl, the game places you directly into the shoes of protagonist Gordon Freeman. Boots clanking against the metal floor, you rush between each end of the carriage, peering out to marvel at the underground laboratories of the Black Mesa Research Facility.

Half-Life isn’t so much remembered for the story it tells, but how it tells it. For Valve, the medium has always been the message, and its games are built on this simple purity: give the player an avatar, and then ground them in the world. For better or worse, the studio has dedicated itself to the player’s absolute presence in an environment. Gordon’s silence in conversations can be awkward or even jarring, but at no point is there a disconnect between the player and their virtual embodiment, and that’s to be admired. Valve has heavily invested in the idea of physicality. A deft world-builder, its virtual environments consistently take on a believable, material sense.

When Half-Life: Alyx was announced at the end of last year, there was some surprise at the fact Valve had chosen to make the game exclusive to virtual reality. But it also makes a lot of sense. Far from being an out of the blue announcement, the jump to VR isn’t just some cynical business move to sell the Valve Index headset, but an effort to continue and build upon traditional storytelling techniques exemplified by those earlier games. The Half-Life series has always been about delivering players this immersive, tangible experience, as well as drawing them ever closer into beautifully realised locations like City 17. These are things the virtual reality medium excels at.

Big in 2020: Half-Life: Alyx is the prequel nobody knew to ask for

The original Half-Life was innovative in terms of its commitment to a singularly coherent avatar and world, but some of its most memorable moments, like the tram-ride, are really all about the action of observation. Half-Life 2 begins similarly, although this time with a train ride into the centre of City 17.

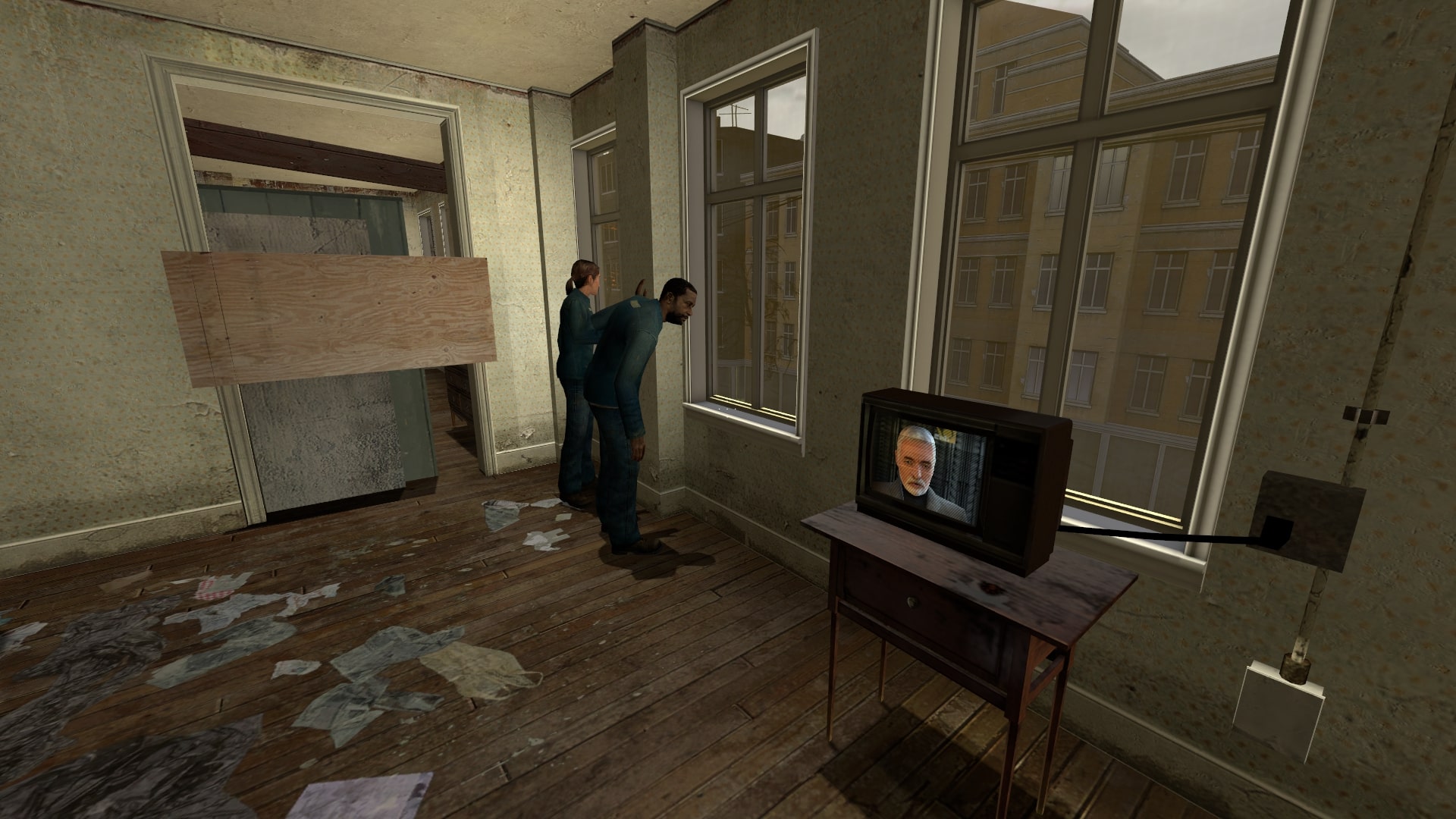

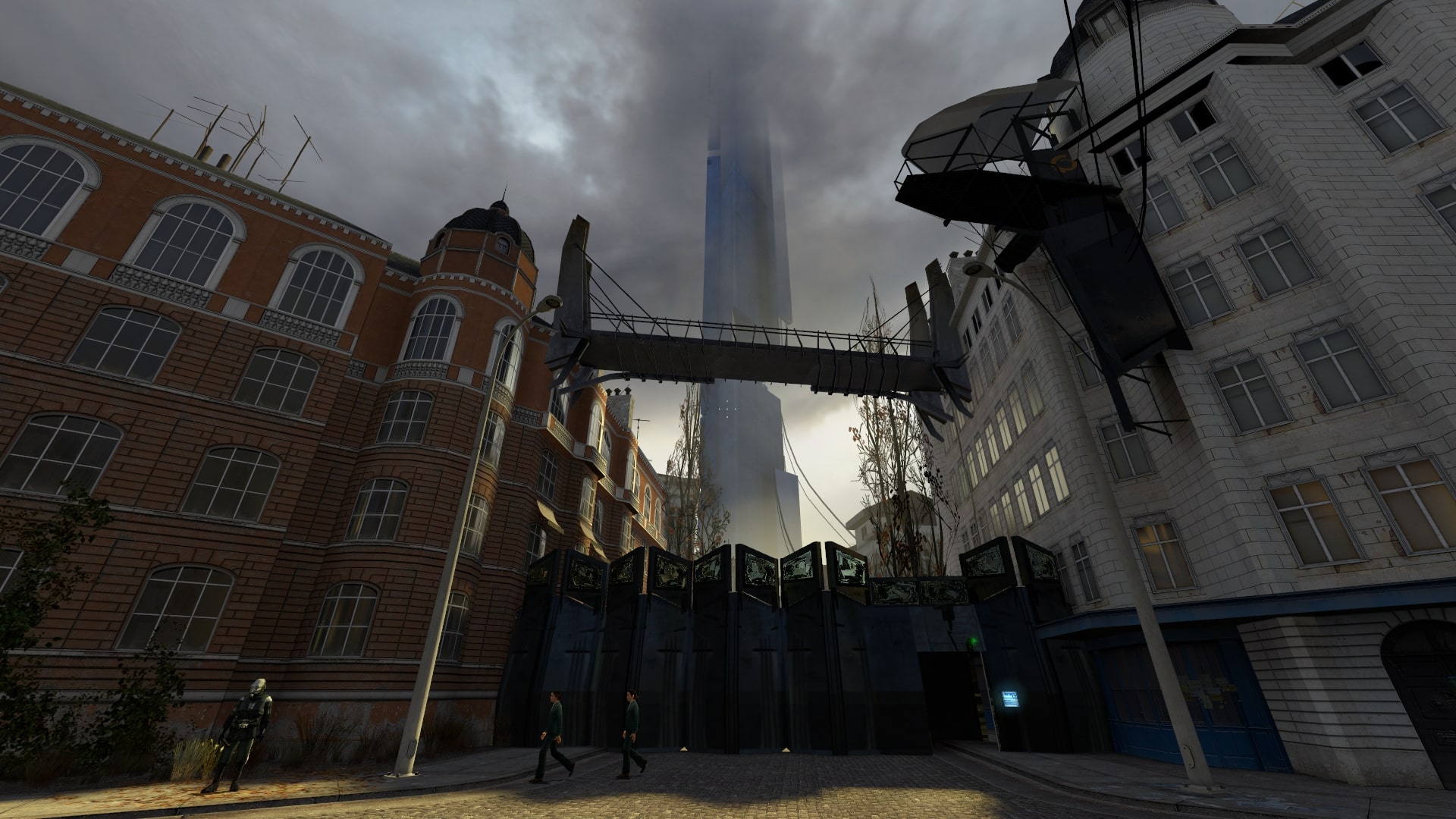

As the train pulls into the station, and you begin to make your way through a set of checkpoints, you witness several scenes in the background: dictator Wallace Breen's face beamed onto holographic screens, enslaved aliens sweeping trash from the floor, bewildered civilians conversing in hushed voices whilst Combine police bully and harrass people. All of these going-ons - as well as the various environmental elements like propaganda posters, graffiti, and pockets of heaped trash - tell us something about the world and what’s going on in it.

Observation is core to the Half-Life series, and it’s something VR can accentuate. Placing you directly behind the eyes of Gordon and letting the player’s sight wander, you can expect Valve to incorporate a lot of these observational moments into Half-Life: Alyx. The minutiae of City 17 will also undoubtedly benefit from the change in interface. Christine Phelan, an animator working at Valve, has already described how VR “affects the entire way you carry yourself in the environments, how you observe your surroundings [and] how you perceive scale.”

Imagine looking up at the towering, monolithic Citadel looming just beyond, whilst Scanner drones and “Manhacks” flit around the airspace of your immediate vicinity. City 17 was made to raise heads, and we can probably expect a lot of that same scope and verticality in Half-Life: Alyx.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

A world at your fingertips

At release, Half-Life 2 famously set new thresholds for video game technology with its groundbreaking physics system. From its opening moments, we see empty cans and noodle-packaging brushed back and forth by a Vortigaunt janitor’s broom. You’re even forced to push your avatar’s body up against the turnstiles in order to reach the next area, before a Combine guard forces you to pick up a can and place it into a nearby rubbish bin.

You can, of course, propel it at him instead, watching as the object bounces into the distance whilst you receive an angry shove in return. Whether you do your duty or bounce the can off the guard’s forehead, Valve is teaching you, well before you attain the Gravity Gun, that this world is one made up of physical properties, and they're open to manipulation.

That Gravity Gun may be gone for Half-Life: Alyx, but it's arguably been replaced by something even more powerful, our very own hands, which can be used to pick up and interact with objects around us via a set of finger-tracking VR controllers. It brings you closer to the world, allows you to really put yourself in Alyx's position, and connect with City 17 in a much more intimate fashion.

"City 17 was made to raise heads, and we can probably expect a lot of that same scope and verticality in Half-Life: Alyx."

It isn’t unreasonable to think Half-Life: Alyx might work without VR, especially as a non-VR version, or a player-built mod, is pretty likely. After all, Half-Life 2 immersed us all well enough back in 2004 without the need for a wireless headset. But the Half-Life series is uniquely positioned to make the most out of this still growing technology, with Valve's core tenants of player immersion synchronising near perfectly with that of VR's potential as a portal to other worlds.

When I think of what I love about Half-Life 2, I think of City 17. More specifically, I think of its abandoned play parks, surrounded on all sides by grey concrete, and characteristic of some of the real places that influenced its design; Sofia, Belgrade, and St. Petersburg. These playgrounds are areas of profound resonance. If you stop to listen, you can hear the faint, ghostly voices of children playing. Brush by the swings, and they'll gently drift back and forth, and - just for a second - it's as if you’re really standing there. Any technology that can bring us a step closer to that depth of feeling is worth its growing pains.

For more, check out the best VR games to play right now, or watch the video below for our latest episode of Dialogue Options.

Ewan Wilson contributes long-form, in-depth features, interviews, and reviews to a variety of publications. While you can frequently find him waxing lyrical about the intersection between video games and architecture here at GamesRadar+, he has also contributed to outlets like Edge magazine, Eurogamer, NME, Polygon, VICE, The Verge, Wireframe magazine, and so many more. His words can also be found in the fantastic gaming architecture zine Heterotopias.