How can we give comic artists more credit? Ask Uncle Creepy

How Do We Give Comic Artists More Credit? Ask Uncle Creepy

While promoting his behind-the-scenes book Watching the Watchmen, Dave Gibbons shared with Wired a personal frustration. "People unacquainted with graphic novels, including journalists, tend to think of Watchmen as a book by Alan Moore that happens to have some illustrations," he said. "And that does a disservice to the entire form."

Though that interview happened nearly 12 years ago, the problem of artist under-appreciation is one that still plagues the comic industry. In fact, if low-attendance comic convention panels and slim social media followings tell us anything, it's a problem even for people who are acquainted with graphic novels. So, what's to be done? How can comic publishers try to give their artists the same household name-status as their writers? There's a myriad of ways to answer, but the simplest is probably to look at the publisher that already did. Dim the lights, we're about to get Creepy.

Creepy began its run in 1964, after original editor Russ Jones pitched the magazine to Famous Monsters of Filmland publisher John Warren. The magazine followed in the tradition of EC Comics; it was a short-form horror anthology with a host, aptly named Uncle Creepy.

In its heyday, Creepy boasted artists with titanic impact on the medium. Alex Toth, Neal Adams, even Steve Ditko joined its ranks of talent, packing 48 pages each month with black & white horror. Under the leadership of renowned comics editor Archie Goodwin (who also wrote some of the stories), the magazine earned many fans during its first seventeen issues, spawning two sister publications: Eerie and Vampirella. Yes, that Vampirella.

Of course, it won't surprise too many familiar with Archie Goodwin that, at a magazine which he edited, artists were treated well. Goodwin is often lauded as one of the great comic editors to ever live, with The Essential Guide to World Comics going so far as to call him "best-loved comic book editor, ever." And the way Goodwin approached artists at Creepy suggested nothing different. Goodwin would start stories with what each artist liked to draw, then write the plots based on their preferences. Not only did this ensure an enthusiastic performance from the artists, it put the onus on the artist as the primary creative force.

Once the stories were created and in the magazine, the creative team would be credited with the artist first and writer second. It may seem like a small change to make, but the first credit slot goes a long way in highlighting a book's artist. In fact, DC attempted this with its 'New Age of DC Heroes' line as part of a push to better credit artists, to somewhat muddled success. In addition to the order, Creepy also broke its credits into two categories; art & script, two distinct parts of a larger whole.

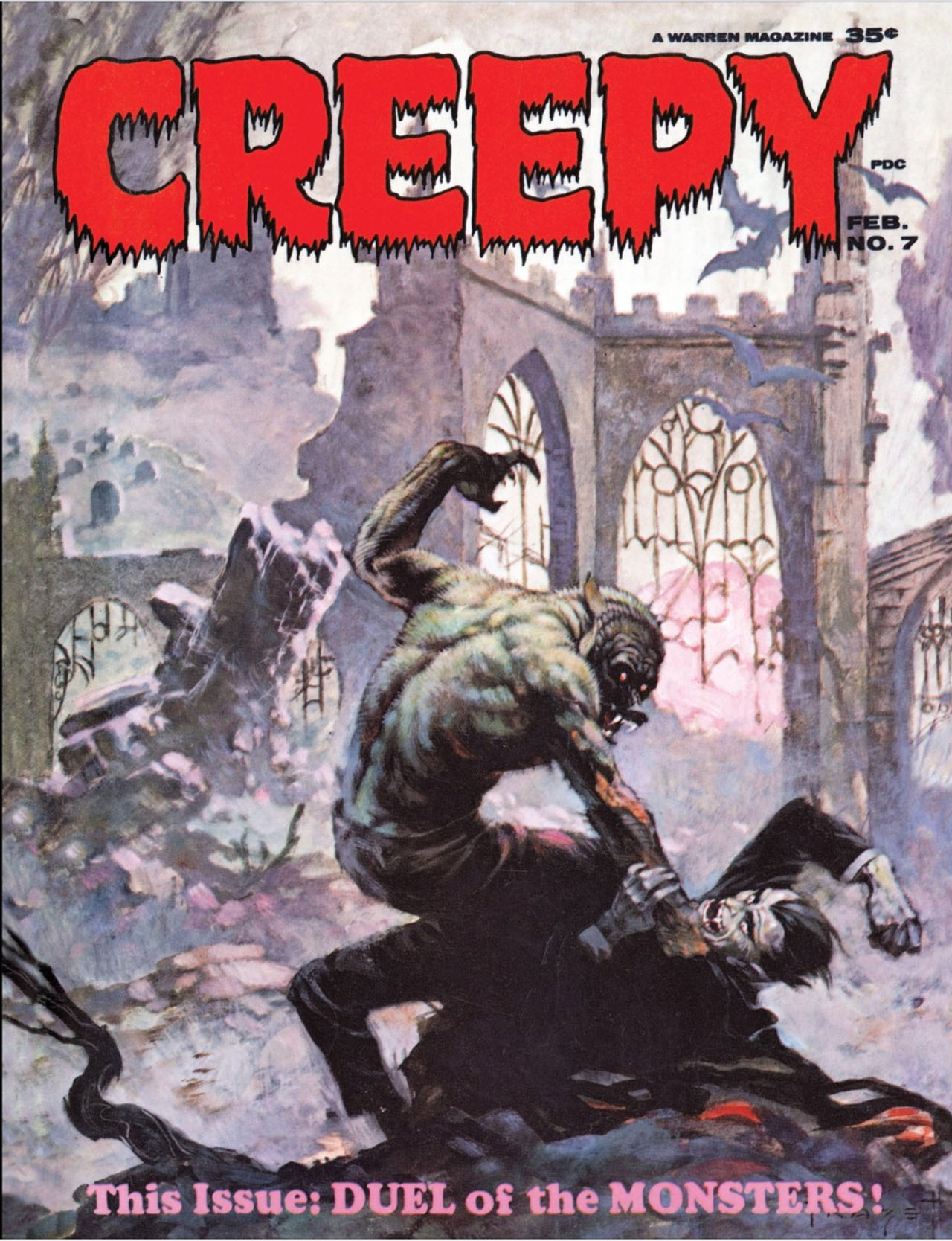

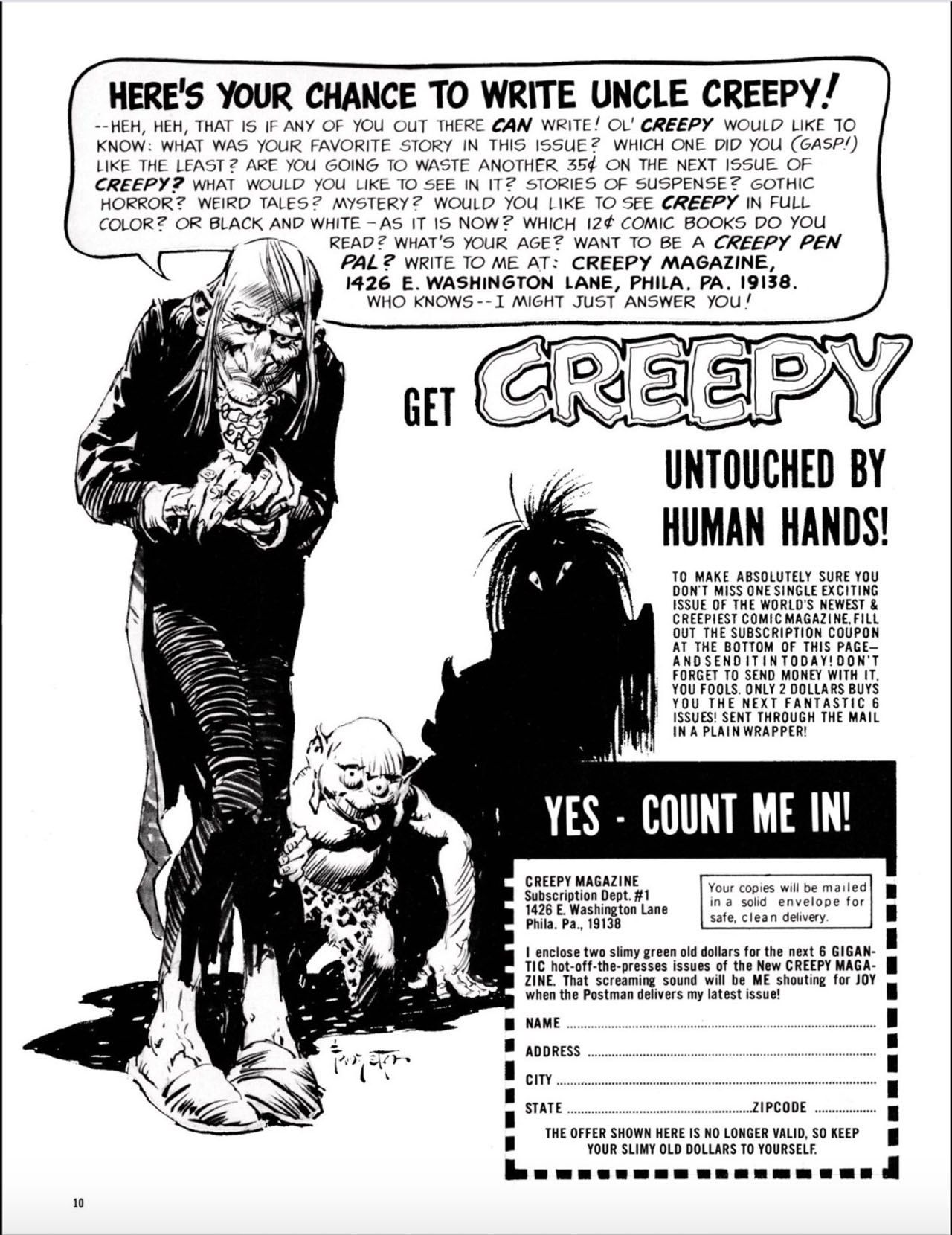

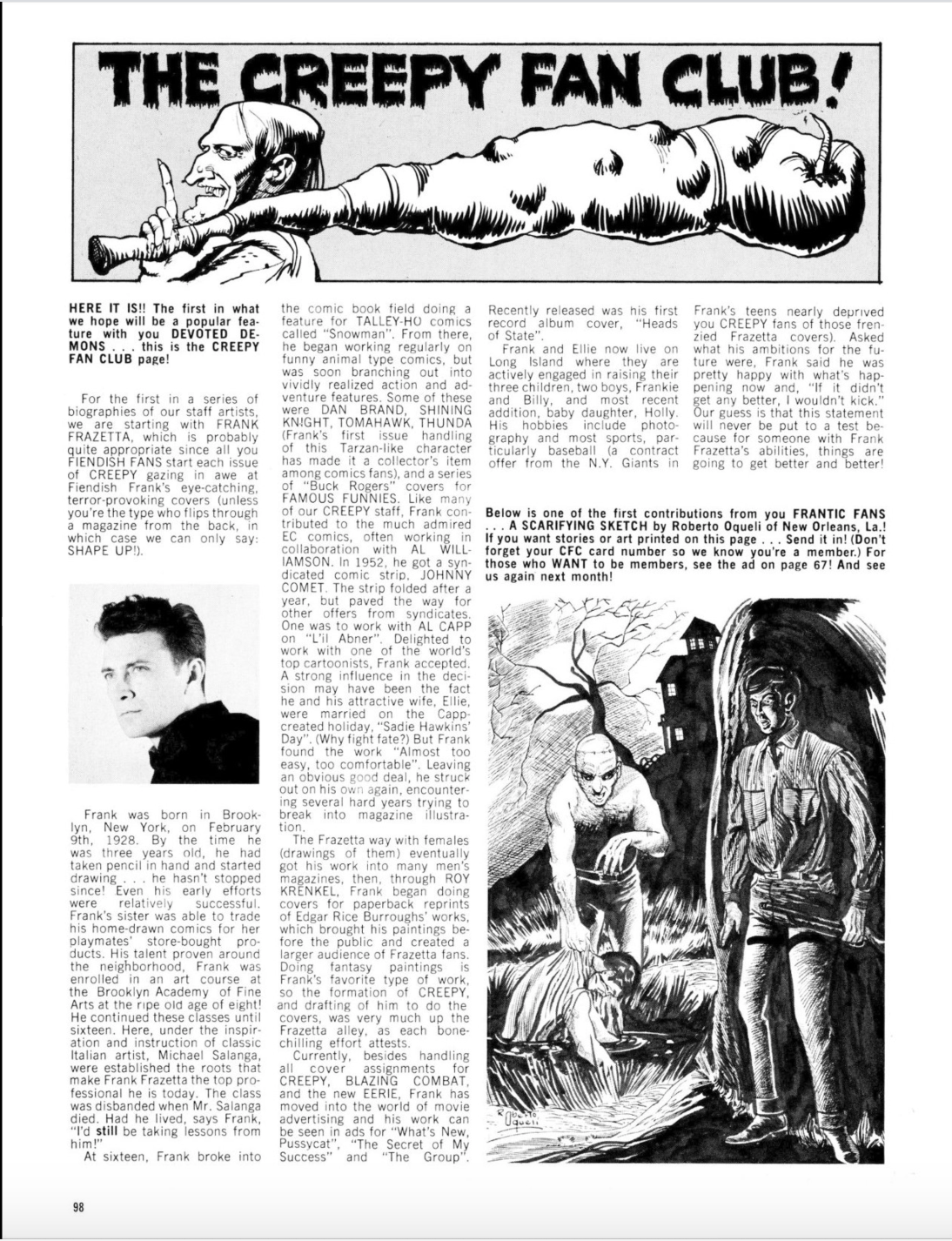

Eventually, Creepy took their artist appreciation a step further. Starting with Creepy #7, the magazine began including spotlights of their artists. These one-page, usually humorous pieces would contain a short biography of their life before comics, how they came into the business, and what they were working on at that moment. These one-pagers, labeled the 'Creepy Fan Club,' were placed in between the magazine's stories. However, to really appreciate their effectiveness, you’d have to look in the fan letters' section.

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

In Creepy #2, the first to feature a 'Dear Uncle Creepy' letters page, a total of 15 fan letters were printed. Only two of them praised one of Creepy's artists by name. Of the 15 published in Creepy #3, only five mentioned them. In #5, the numbers from #2 were repeated, and that low percentage of letters that praised artists by name held for the earliest issues of the magazine. Then came Creepy #7, and with it, the Creepy Fan Club page.

Praise for artists by name in Creepy began to climb. In #9, five out of ten letters gave specific artists shout-outs. In #12, of the twelve letters, seven of them gave credit to the artists' work. In #15, of the eight letters that were printed, all but one called out the work of one particular artist. Compare that to the numbers in Marvel's The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl. Of the forty-three fan letters published in the first volume's trade paperback, only four mentioned artist Erica Henderson's work.

This is not to say artists are the only people who are overlooked in the comic world. Research colorists and especially letterers for proof. Nor is it to say that Creepy completely solved the problem in how it handled its artists. But Creepy did manage to send a message that some current comics do not. That message is, to quote Gibbons, that comics are not stories that have illustrations, but that comics are illustrations. By putting those illustrator’s names in the first spot on the page, by dedicating physical space to celebrating them within the magazine, Creepy made sure that was a truth readers of their comics magazine wouldn't forget.

Grant DeArmitt is a NYC-based writer and editor who regularly contributes bylines to Newsarama. Grant is a horror aficionado, writing about the genre for Nightmare on Film Street, and has written features, reviews, and interviews for the likes of PanelxPanel and Monkeys Fighting Robots. Grant says he probably isn't a werewolf… but you can never be too careful.