Love GTA, Heavy Rain and Resident Evil? Well Deadly Premonition is better than all of them. Here's why

You probably haven't played one of the best games of this generation so far. Here's why you should

"So bad it's good". That's the cliche you'll often hear trotted out to describe Deadly Premonition, the open-world, survival-horror, supernatural (or is it?) murder-mystery epic from Access Games. The game has built a cult following since its release last year, gaining plaudits and derision in equal measure for itsunique characterwriting, shaky, last-gen production values, 'idiosynchratic' game mechanics and general strangeness. It's garnered review scores ranging from a miserable 2 all the way to a perfect 10, and if you listen to ourTalkRadar UK podcastyou've probably heard me banging on about it a great deal.

The thing is, that "so bad it's good" appraisal is deeply inaccurate. Naive, even. Because while Deadly Premonition in many ways veers far from the currently accepted standards of modern game production, it is in no wayan ironic guilty pleasure. It's actually "so good it's brilliant". Play the game, get to know it, really understand it, and you'll realise that in many ways it's actually one of this generation's most inspired and cleverly-designed works. But before you do that,read on. Because I'm going to try to explain why. We never reviewed it, you see, so I've decided to make up for that with a whole lot of beard-stroking discourse.

It has one of the most believable open-worlds around. Fact

What makes a believable video game world?A terrifyingly life-like physics system?An ultra-sophisticated damage model? Mega-resolution textures sharper than the eye can see, and twelvety-billion polygon models across the board, right down to the tiniest fledgling petunia?

No. And additionally, no, no and no.

The sense of an environment being a real, living, functioning place is what makes a believable game world, and creating that feeling is all about the people and social workings you put in it. Shenmue’s Tokyo and Hong Kong? Felt real, because every character populating them was an individual, and all had their own simulated lives, seemingly going on independently from your quest. Gears of War’s Sera? Feels like a bunch of corridors full of waist-high walls and things to shoot, because it is. Unreal 3 rendering and decades of back-story or not, that whole world is just a shooting gallery punctuated with dialogue, and populated by about ten people. Deadly Premonition takes Shenume’s example, opting for a ‘less is more’ approachwhile focusing onthe really important things. ie. the small, human details. It also looks a bit like an HD Dreamcast game, but that’s just a coincidence.

Deadly Premonition, you see, makes every person count. There’s a sparsity of population compared to something like GTA, but that’s all very plausible for the setting.Its setting of Greenvaleisn’t a huge, thriving metropolis with a million people wandering the streets. It’s a small, rural, Pacific North-Western town. You’ll often drive for a couple of miles without seeing anyone walking the streets, and vehicular traffic isn’t much more frequent. But the game wouldn't work anywhere near as well if the place was packed with people, because that sparsity is used brilliantly as a narrative device.

Deadly Premonition’s visible population is made up almost entirely of its large cast of characters. And everyone, from major NPC to crazy old lady, has an important part to play. And you’ll run into them a lot. Because everyone has their own daily routine, involving home-life, work, travel, and general pottering around town. And everyone is available to form a relationship with right from the start.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

You see that’s the eternal irony with open-world games. They usually aren’t open at all. Even if certain areas of the map aren’t locked down by plot-specific timing (as is almost invariably the case), then their inhabitants definitely are. Try as you might to find them, main characters just don’t make an appearance in a sandbox game’s reality until the main storyline dictates that they will. Until then you’re stuck with Billy-Joe and Mary-Kate Scenery-Filler, and their fourteen interchangeable faces. The characters who matter just don’t exist until the game says it’s convenient for them to. It feels horribly artificial.

Deadly Premonition’s world and its people though, are all there waitingfor you from the start. The whole map is open. The people are going about their day-to-day business. Want to follow the main story missions until they all turn up in their conventional, plot-specificplace? Fine. But if you want, you can ignore the story for a couple of days and start exploring and investigating the place in your own time and on your own terms. You know, in character, like an FBI agent would.

Because that’s the other irony with the supposed freedom of open-world games. Not only is exploration of the worldlargely restrictive of your own personal input, your character’s personal development and journeythrough that world is prettylocked down as well. Yeah, you can pump iron or change your hair sometimes, but that doesn’t really mean anything. At the end of the day, you’re still looking at a bunch of pre-set missions and pre-set actions and pre-set times in pre-set places. It's a linear game with the illusion of freedom tacked on by way of someunrelated sandboxcarnagestapled tothe side. Want things another way? Want to really play a role in this ultra-detailed simulation of reality? Tough. The game doesn’t work that way.

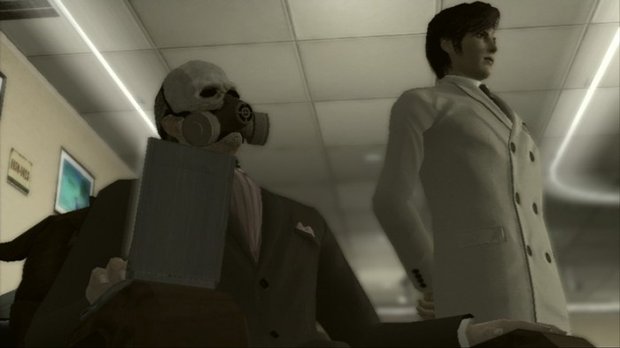

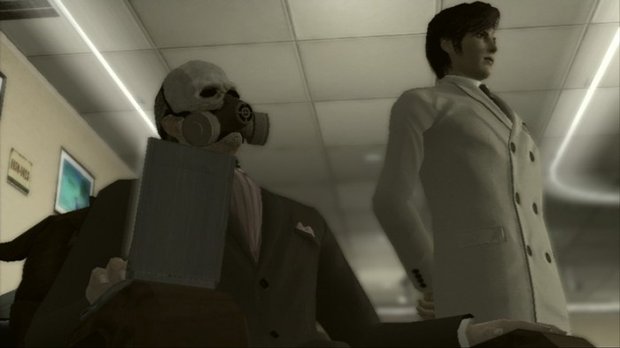

Above: Just to prove I'm not lying

But Deadly Premonition does. Opening exposition established, you’re let loose to get to know the world in any way you want. Every cast member is flagged up on the map as they move around, initially labelled simply “Suspect”. Track them down though, interrogate them, find out who they are and theorise on how they fit into the overall plot, and they’ll show up on the map – and in the game world – labelled with their real name.

It’s impossible to stress how important this is. The seemingly innocuous process of seeing someone you’ve got to know on your own terms pottering around town on their day-to-day business creates an immense bond with them as a character. They’re not NPCs you’ve seen in a prescribed, time-released cut-scene. They’re real people you’ve met and formed a relationship with. And the way those relationships develop is something you have power over as well. Meet someone for the first time at their home, before they’re ‘supposed’ to appear in the main story missions, and you’ll get different dialogue, different initial reactions to each other, and different versions of your later scenes with them further down the line.

With all of this combined with a living, breathing society going on independently from your investigation, the sense of place can become mesmerising at times. Whether it’s little details likenoticing the townsfolk allstart to maketheir own way to a town meeting at the same time as you drive there yourself, or more overt occurrences like monitoring a particular NPC’s movements on the map so that you can track them to trigger a side-mission (while cross-referencing the time of day, and whether they’ll be accessible, or busy with work or home-life), Deadly Premonition feels more real than any other open-world I’ve played. Forget the looks. This place feels alive. Greenvale is a real town, and once you get there you will not want to leave.

Next: Making you love a schizophrenic weirdo

The thing is, that "so bad it's good" appraisal is deeply inaccurate. Naive, even. Because while Deadly Premonition in many ways veers far from the currently accepted standards of modern game production, it is in no wayan ironic guilty pleasure. It's actually "so good it's brilliant". Play the game, get to know it, really understand it, and you'll realise that in many ways it's actually one of this generation's most inspired and cleverly-designed works. But before you do that,read on. Because I'm going to try to explain why. We never reviewed it, you see, so I've decided to make up for that with a whole lot of beard-stroking discourse.

It has one of the most believable open-worlds around. Fact

What makes a believable video game world?A terrifyingly life-like physics system?An ultra-sophisticated damage model? Mega-resolution textures sharper than the eye can see, and twelvety-billion polygon models across the board, right down to the tiniest fledgling petunia?

No. And additionally, no, no and no.

The sense of an environment being a real, living, functioning place is what makes a believable game world, and creating that feeling is all about the people and social workings you put in it. Shenmue’s Tokyo and Hong Kong? Felt real, because every character populating them was an individual, and all had their own simulated lives, seemingly going on independently from your quest. Gears of War’s Sera? Feels like a bunch of corridors full of waist-high walls and things to shoot, because it is. Unreal 3 rendering and decades of back-story or not, that whole world is just a shooting gallery punctuated with dialogue, and populated by about ten people. Deadly Premonition takes Shenume’s example, opting for a ‘less is more’ approachwhile focusing onthe really important things. ie. the small, human details. It also looks a bit like an HD Dreamcast game, but that’s just a coincidence.

Deadly Premonition, you see, makes every person count. There’s a sparsity of population compared to something like GTA, but that’s all very plausible for the setting.Its setting of Greenvaleisn’t a huge, thriving metropolis with a million people wandering the streets. It’s a small, rural, Pacific North-Western town. You’ll often drive for a couple of miles without seeing anyone walking the streets, and vehicular traffic isn’t much more frequent. But the game wouldn't work anywhere near as well if the place was packed with people, because that sparsity is used brilliantly as a narrative device.

Deadly Premonition’s visible population is made up almost entirely of its large cast of characters. And everyone, from major NPC to crazy old lady, has an important part to play. And you’ll run into them a lot. Because everyone has their own daily routine, involving home-life, work, travel, and general pottering around town. And everyone is available to form a relationship with right from the start.

You see that’s the eternal irony with open-world games. They usually aren’t open at all. Even if certain areas of the map aren’t locked down by plot-specific timing (as is almost invariably the case), then their inhabitants definitely are. Try as you might to find them, main characters just don’t make an appearance in a sandbox game’s reality until the main storyline dictates that they will. Until then you’re stuck with Billy-Joe and Mary-Kate Scenery-Filler, and their fourteen interchangeable faces. The characters who matter just don’t exist until the game says it’s convenient for them to. It feels horribly artificial.

Deadly Premonition’s world and its people though, are all there waitingfor you from the start. The whole map is open. The people are going about their day-to-day business. Want to follow the main story missions until they all turn up in their conventional, plot-specificplace? Fine. But if you want, you can ignore the story for a couple of days and start exploring and investigating the place in your own time and on your own terms. You know, in character, like an FBI agent would.

Because that’s the other irony with the supposed freedom of open-world games. Not only is exploration of the worldlargely restrictive of your own personal input, your character’s personal development and journeythrough that world is prettylocked down as well. Yeah, you can pump iron or change your hair sometimes, but that doesn’t really mean anything. At the end of the day, you’re still looking at a bunch of pre-set missions and pre-set actions and pre-set times in pre-set places. It's a linear game with the illusion of freedom tacked on by way of someunrelated sandboxcarnagestapled tothe side. Want things another way? Want to really play a role in this ultra-detailed simulation of reality? Tough. The game doesn’t work that way.

Above: Just to prove I'm not lying

But Deadly Premonition does. Opening exposition established, you’re let loose to get to know the world in any way you want. Every cast member is flagged up on the map as they move around, initially labelled simply “Suspect”. Track them down though, interrogate them, find out who they are and theorise on how they fit into the overall plot, and they’ll show up on the map – and in the game world – labelled with their real name.

It’s impossible to stress how important this is. The seemingly innocuous process of seeing someone you’ve got to know on your own terms pottering around town on their day-to-day business creates an immense bond with them as a character. They’re not NPCs you’ve seen in a prescribed, time-released cut-scene. They’re real people you’ve met and formed a relationship with. And the way those relationships develop is something you have power over as well. Meet someone for the first time at their home, before they’re ‘supposed’ to appear in the main story missions, and you’ll get different dialogue, different initial reactions to each other, and different versions of your later scenes with them further down the line.

With all of this combined with a living, breathing society going on independently from your investigation, the sense of place can become mesmerising at times. Whether it’s little details likenoticing the townsfolk allstart to maketheir own way to a town meeting at the same time as you drive there yourself, or more overt occurrences like monitoring a particular NPC’s movements on the map so that you can track them to trigger a side-mission (while cross-referencing the time of day, and whether they’ll be accessible, or busy with work or home-life), Deadly Premonition feels more real than any other open-world I’ve played. Forget the looks. This place feels alive. Greenvale is a real town, and once you get there you will not want to leave.

Next: Making you love a schizophrenic weirdo