With Nintendo closing 3DS and Wii U digital stores, where does that leave video game preservation?

With less access to older games, we're surely losing a link to the past

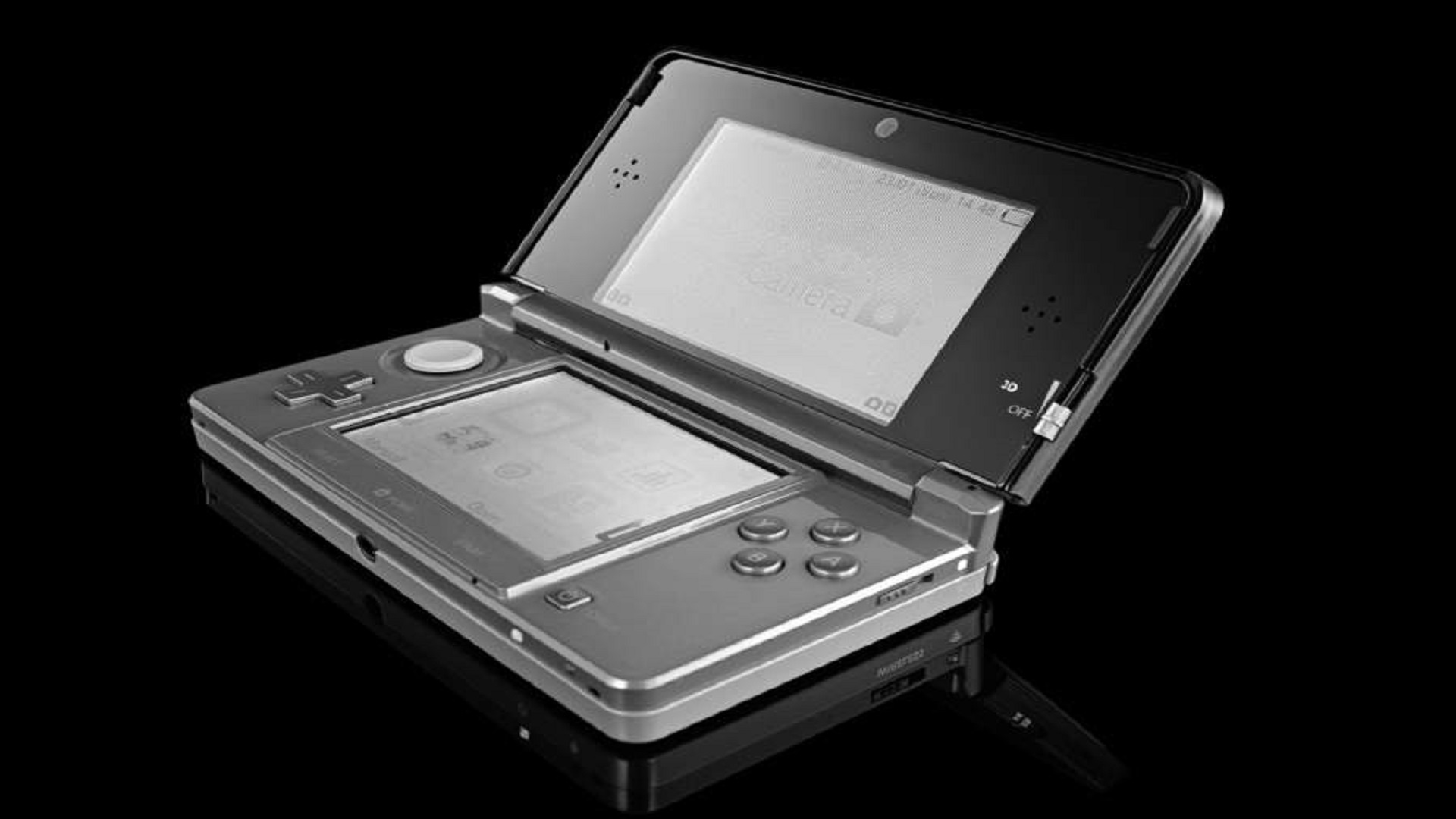

One thousand. That, give or take, is the number of digital-exclusive games estimated to become unavailable for purchase once Nintendo's 3DS and Wii U digital stores are shuttered. For everyone except those who already own affected games – a situation soon to present challenges of its own, given that credit card and eShop Card functionalities will be disabled in May and August respectively – they will effectively vanish in March 2023, unable to be downloaded ever again.

Nintendo has argued that the move is part of the "natural lifecycle for any product line as it becomes less used by consumers over time". In a now-deleted statement, the company pointed to the availability of over 130 "classic games" on its subscription service Switch Online as "an effective way to make classic content easily available to a broad range of players". But that service doesn't include either of these consoles' libraries.

So, how does it feel to the developers of those games which are about to disappear? "Tank Troopers and Steel Diver were actually [two] of the few titles specifically designed for 3DS, so I do find it a shame that the hardware required to play it properly is now discontinued," says Giles Goddard, CEO of Kyoto-based developer Vitei. "But the retro game community is very creative and there's some really cool tech around nowadays, so I think people will find a way to keep playing old games as intended."

Gone but not forgotten

"This is recognising that games are an absolutely crucial part of our shared popular culture heritage."

While Goddard is sad about the 3DS eShop closure, he also sees it as an inevitability. "It's extremely rare to see a 3DS being played nowadays and the costs of running the service I can imagine are quite high," he says. "Nintendo have to draw the line at some point, and I think ten years for a handheld console is a pretty good lifetime."

Presenting a particular problem for the developers of Wii U and 3DS games are the unique hardware specifications – which, ironically, were exactly what attracted Austrian developer Broken Rules to Wii U in the first place. "I really liked the idea of having two screens and some people in the room not seeing the same thing," says Broken Rules CEO Felix Bohatsch. Its 2D flying game Chasing Aurora was an eShop launch title which embraced these design opportunities with a Hide And Seek mode pitting one GamePad user against multiple Wii Remote players sharing the television screen – a local multiplayer experience that can't be translated to other hardware. "When the Wii U didn't succeed on the marketplace, financially or with the userbase, that's when this design space was lost," Bohatsch laments.

But what about the broader view? In some ways, gaming's past has never been more celebrated than it is right now. Studios including Bluepoint Games are setting the bar with high-quality reimaginings of classics such as Demon's Souls, while the likes of Nier Replicant are redefining what a remaster can be, giving previously overlooked games a second chance in the limelight. A wave of mini consoles has brought us facsimiles of old hardware preloaded with curated libraries of games. But this curation is indicative of the biggest drawback to the current approaches taken towards preservation: they fail to encompass the totality of retro console libraries.

Even Microsoft, which has championed backwards compatibility on its consoles – with head of Xbox Phil Spencer encouraging the industry to adopt "legal emulation" in a 2021 interview – last year topped out its list of Xbox and Xbox 360 games that can be played on current-gen hardware at just over 700. This is the most involved effort by any platform holder, and even that can't quite match the number of Wii U and 3DS titles about to be lost.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

This article first featured in Edge Magazine – check out subscription options at Magazines Direct

For Professor James Newman, co-founder of the Videogame Heritage Society (VHS), these store closures are a reminder of the fragility of digital media. "Without concerted, positive preservation efforts, we are going to lose access to games," he says. "We already have." Led by the Sheffield-based National Videogame Museum (NVM), the VHS aspires to bring together various preservation stakeholders to pool resources under a shared banner, with the likes of the Science Museum Group, the British Library and the BFI among its founding members. This includes everything from 'data forensics' (the process of extracting software from obscure and damaged physical materials) to preserving the material heritage of videogames – think boxes, controllers and consoles. In the face of digital store closures, Newman feels there is an opportunity for heritage organisations such as the VHS to work alongside developers and publishers in order to work out what long-term preservation looks like for video games. It's a process which might require entirely rethinking the question: what exactly do we mean by 'preservation'?

"The most obvious answer to that is: we want to continue to be able to play games in the future," Newman says. "And to some extent preservation then looks like it's harming the bottom line [for developers and publishers], it looks like you are just providing access to games which somebody else could be commercialising at some point in the future." However, Newman proposes a method focusing on preserving games as experiences and cultural heritage objects, rather than solely as playable experiences, hundreds of years into the future. "Then you start to think, well, this maybe isn't only a software and emulation problem: maybe actually we're talking about a documentary approach to this."

For many, the idylls of Animal Crossing: New Horizons provided a much-needed safe space during the height of COVID-19, sparking a surge in popularity for Nintendo's social sim that extended as far as politicians and talk-show hosts. The NVM's Animal Crossing Diaries multimedia exhibit seeks to reflect just that, portraying the "everyday experiences of a historic time". In one section, a scanned handwritten journal documents one person's life through the pandemic, with notes expressing how "Animal Crossing continues to be a safe haven from disaster". In another, a video showcases a fancy-dress birthday party.

"That was basically my full-time work for the majority of six months, going through and making sure all these things were stored correctly digitally, making sure we all had the right permissions. And that's just for a curatorial project," NVM curator Dr Mikey Pennington explains. "That work is amplified exceptionally when we talk about the behind-the-scenes of a development team, because they just deal with masses of data every day."

Newman argues that preserving the ways in which we interact with games – whether through watching or streaming speedruns, using them as templates for creative projects, or simply hanging out in their shared social spaces – is just as important as the games themselves. He likens it to viewing a guitar in a gallery: you might be able to pick it up and strum out a few chords, but that doesn't give you a sense of the compositions created using the instrument, as well as its cultural impact. "If you're going to preserve Minecraft, having a playable version in the future definitely is the valuable thing," he explains. "But also the careers, the new ways of reaching players, new ways of marketing, new forms of celebrity: that's why I'm really interested in that complementary approach, which documents the cultural meaning of those games."

This is an archivist's way of looking at things, of course, not necessarily the focus for these games' creators. While Bohatsch acknowledges the importance of the culture surrounding games, he feels that keeping Chasing Aurora playable is the ideal. "I make games because I want them to be played," he says. "For me, the ideal form to experience my creation is that it be played."

"Nintendo have to draw the line at some point, and I think ten years is a pretty good lifetime."

Ensuring this remains possible, though, might require straying beyond the neat lines of officially sanctioned emulation. While platform holders (Nintendo in particular) are known for taking a rather less charitable approach to the topic, Bohatsch is fairly relaxed about emulation of his own games. "I'm not going to go after kids or teenagers who are getting our games to be played on platforms without paying." He's not necessarily talking about piracy of more recent releases, on whose sales Broken Rules relies in order to stay afloat. "[But] as soon as the main years of income from our games are out, it's a totally different picture. It would be great to see that Chasing Aurora can run on an emulated Wii U on a modern desktop. That would be really great for us, because then we know our game can be played for longer than Nintendo cares for it."

For Pennington, one of the goals of the VHS is to serve as a bridge between preservation institutions and individuals already involved in DIY game preservation, including grassroots emulation projects. "A lot of the knowledge that people potentially have about preserving source code and digital games lies in individuals that, at the current moment – although the VHS has tried to bridge this gap – it's largely left untapped," he says. "Fans of games, specifically, hold the key to being able to preserve this work and preserve these materials."

Newman also notes the possibilities emulation opens up for exhibiting games in a museum setting. Such an approach would allow curators to utilise save states to exhibit specific moments of larger games – for example, a boss battle 20 hours into an RPG – or to enable consistent access to a noteworthy glitch, in a similar manner to displaying specific scenes and frames of a film. "There's some really interesting discussions to be had around emulation," he says, "and shifting the focus away from emulation as being a piracy-enabler to a way of offering innovative access to games which are not particularly conducive to being accessed in gallery spaces."

Not that platform holders necessarily see it the same way. In 2021, American researchers were denied a copyright exemption appeal for "off-premises access to software", something that the Entertainment Software Association – which includes Nintendo as a member – stated would "risk the possibility of substantial market harm". The Video Game History Foundation criticised Nintendo's ESA membership in light of its store closure announcements, stating that "not providing commercial access is understandable, but preventing institutional work to preserve these titles on top of that is actively destructive to videogame history".

Ultimately, Pennington feels the game industry's approach to preservation has been overly wary, a result both of harm caused by potential leaks and the desire to rerelease and thus monetise older titles. As for preserving the experience of playing Wii U and 3DS games on their original hardware, he theorises that "bespoke packages" could be released for modern platforms – re-released Wii games on Switch coming bundled with a Wii Sensor Bar, for instance. However, even this approach would fail to replicate the various idiosyncrasies of something like a 3DS, and would again limit access to publisher-curated lists. "It's a real challenge to try and think about how practically you could re-monetise [3DS] and also still preserve the original sense of playing," Pennington says. "I think that's why you just see remasters being a more straightforward way of making [games] playable."

Pennington also calls for a system to be implemented for games in a similar manner to the legal deposit system, which requires publishers to provide six named libraries (including the British Library) with copies of all print and digital works published in the UK. "But that doesn't account for all the games previously that have been released and that have just disappeared," Pennington says, noting the impact of the withdrawal of Adobe's Flash player from web browsers in December 2020. While notice of its removal was flagged back in 2017, games using it are now essentially impossible to access, except through community preservation projects such as Flashpoint.

For Newman, the looming spectre of Nintendo's store closures makes creating, and funding, historical archives for games even more important. The NVM is operated by the BGI charity, with certain projects supported by grants – the Animal Crossing Diaries received the Museum Association-run Esmé Fairbairn Collections Fund, for example. Newman would like to see an increase in both industry support and government funding for preservation projects, emphasising the importance of maintaining access to the likes of Nintendo's eShop games to inspire future generations of game developers.

"This isn't just nostalgia, this is recognising that games are an absolutely crucial part of our shared popular culture heritage," Newman says. "And if we do lose access to, and understanding of, them, then I think we lose a really important part of our ability to tell the story of the late 20th [and] early 21st century. Recognising how significant they are should immediately tell us that this kind of work needs to be quite urgently funded."

Bohatsch agrees, calling for an increased focus on preservation from the industry itself in the absence of Nintendo keeping its storefronts alive. "The more games that have been made, the more important it is for younger designers to know what came before them and to have some form of curation and selection that is not based on business, which is what is happening in the [Wii U and 3DS] storefronts," he says. "It's very important that there's preservation, that there's curation from an artistic, creative, or even historical viewpoint. We have this for art, for books, for movies, for music – of course we need this for games as well."

This feature first appeared in issue #370 of Edge Magazine. For more great articles like this one, check out all of Edge's subscription offers at Magazines Direct.

Niall O'Donoghue is a freelance writer and editor, with bylines across the industry including Edge magazine, The Washington Post, The Loadout, GamesIndustry.biz, RPS, and the Irish Times.