Quake turns 25: John Romero looks back on the legendary FPS that almost tore id Software apart

The making of Quake is a story of messy, ambitious development that changed the Doom and Wolfenstein creators forever

Following the news that Quake is being enhanced and re-released for modern platforms to celebrate the 25th anniversary of this legendary shooter from id Software, we thought some of you might like a little history lesson. This making of Quake from the pages of Retro Gamer explores the turbulent development of an FPS classic.

While many gamers didn't become aware of id Software until the release of the firm's genre defining IP Doom in 1993, it had actually been developing first-person shooters for several years before the arrival of its breakthrough title. Furthermore, prior to id's formation the company's founders had spent close to a decade in games development honing their respective skills on an impressive number of releases.

After conquering mainstream gaming with Doom, id next produced a well-received sequel in 1994 with Doom 2 and, buoyed by the follow-up's success, the nine-man team moved on to their next project – Quake – with a belief that they were unstoppable, as id co-founder John Romero recalls. "We had been making games for over 10 years before Wolfenstein, so we were already experts before we got together," Romero beams. "We used to make games in two months – we made 11 games in 1991. so we were fast. Wolfenstein was four people, and it took us four months to make. We got Doom done mostly with only five people, and then we got a sixth person during the last few months. With Quake, there were only nine of us, but by that time everyone on the team was awesome."

Lovecraft calling

"When that decision was made, I basically decided that I was going to be leaving when the game was over"

John Romero

Beyond Quake's striking name, the well-oiled machine known as id further differentiated its latest concept from the Doom franchise when one of Romero's fellow designers introduced him to the Gothic horror writings of cult author H. P. Lovecraft. "Sandy Petersen was a huge H. P. Lovecraft fan," Romero remembers. "I had heard his name, but I thought he was just a classic writer. Sandy basically said: 'Oh, no, no.' He gave me these Chaosium books, and when I read them I was mind-destroyed; I was just blown away by the monsters. so Quake was very inspired by H.P. Lovecraft, as I'd just been exposed to him."

But in order to do justice to Lovecraft's nightmarish fiction, Quake's newfound aesthetic would need to be underpinned by cutting-edge tech, as Romero and his Quake team soon became aware of. "The idea was that we were going to have a full-3D engine that was on the internet and was scriptable in its own language," Romero explains. "We had never done this before, so it was a big technical undertaking, and since we were doing so much new with this engine we thought: 'Well, what can we do that's new in game design? Let's not tie ourselves to what we've done in the past with military themes, but maybe get closer to D&D with Quake'."

However, the sheer complexity of building the tech for Quake resulted in a situation where its engine continually evolved over the course of a year, which hardly helped Romero's efforts to manage the game's design process. "There were ideas of abstract environments – medieval type stuff – but there wasn't any written-down design for Quake during its first year," Romero says of the game's initial design push. "So by November the team was really burned out trying to make a game that didn't really have an identity. They were making a lot of levels and having to delete them and start over because the engine was getting better. But when we got to the end of November, the engine was ready, and so now we could actually design a game around it."

With Quake's underlying tech finally in place, Romero was ready to move on from what he viewed as R&D into full development and to create a game design that matched the innovation of id's recently completed engine. Unfortunately, his exhausted design team felt otherwise. "We had a big company meeting to decide whether we were going to slap Doom-style weapons in and make it a classic FPS, or experiment with some new game design ideas," says Romero. "Some people in the team just said: 'You know what? I'm broken, and I can't do it anymore.' They wanted to just throw Doom-style weapons in there and call it a day. I mean, obviously we were going to make them as good as we could, but we weren't going to be pushing game design in a new direction. So, when that decision was made, I basically decided that I was going to be leaving when the game was over."

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

One last ride

But far from letting this decision sour his approach to Quake's design, Romero instead tried to inject the maximum innovation possible into the project's best level designs, all while respecting the framework established by previous id first-person shooters. "Basically my job after that meeting was to design the game around what we had at that point that made sense and was good," Romero considers. "The guiding light was that we had four 'dimensions' – each one designed by one of the designers. so i designed something very similar to what the game came out to, but a more complex version that had more story elements. But after a month or two of us cranking out levels, I had to simplify it even further because of how long it was taking us. So I basically had to ditch the RPG stuff and just make it a pure shooter."

Of course, without the story elements that Romero had intended to connect Quake's wildly differing levels together with, the developer was left with something of a design challenge, which he ultimately resolved by making his game's hero an inter-dimensional, time-travelling soldier. "I was like: 'Ok, we need to tie all these episodes together somehow; somehow you're going between episodes,'" he says. "'Well, why aren't you a military dude?' and if you were a military dude you needed to be in a military environment and to leave that military environment to enter these 'dimensions.' So I was like: 'I need to come up with a teleporter for this game that doesn't just take you to somewhere in space, but somewhere in time to different dimensions.' So I came up with the name 'slipgate,' and told the artists: 'this is what i'm building. Can you make textures that fit this?'"

Undeterred by the back-to-basics approach forced on Quake's design process, Romero opted to focus on the innovations made possible by the game's highly impressive engine, and in particular its ability to render truly three-dimensional environments. "The goal of Quake's level design was that we needed to explore verticality as much as possible," Romero enthuses, "so you could be under a bridge but be on top of that bridge later. That was a massive change from anything that we had done before, so designing vertically was really important. I had a rule for the designers that if they created a room in Quake and it could be replicated in Doom then they had failed. Every room needed to show the dimensionality of the engine. We were forcing the player to worry more about the environment on multiple planes, instead of like with Doom where your plane was always the horizontal. We were pushing players into the next dimension by enforcing a vertical design."

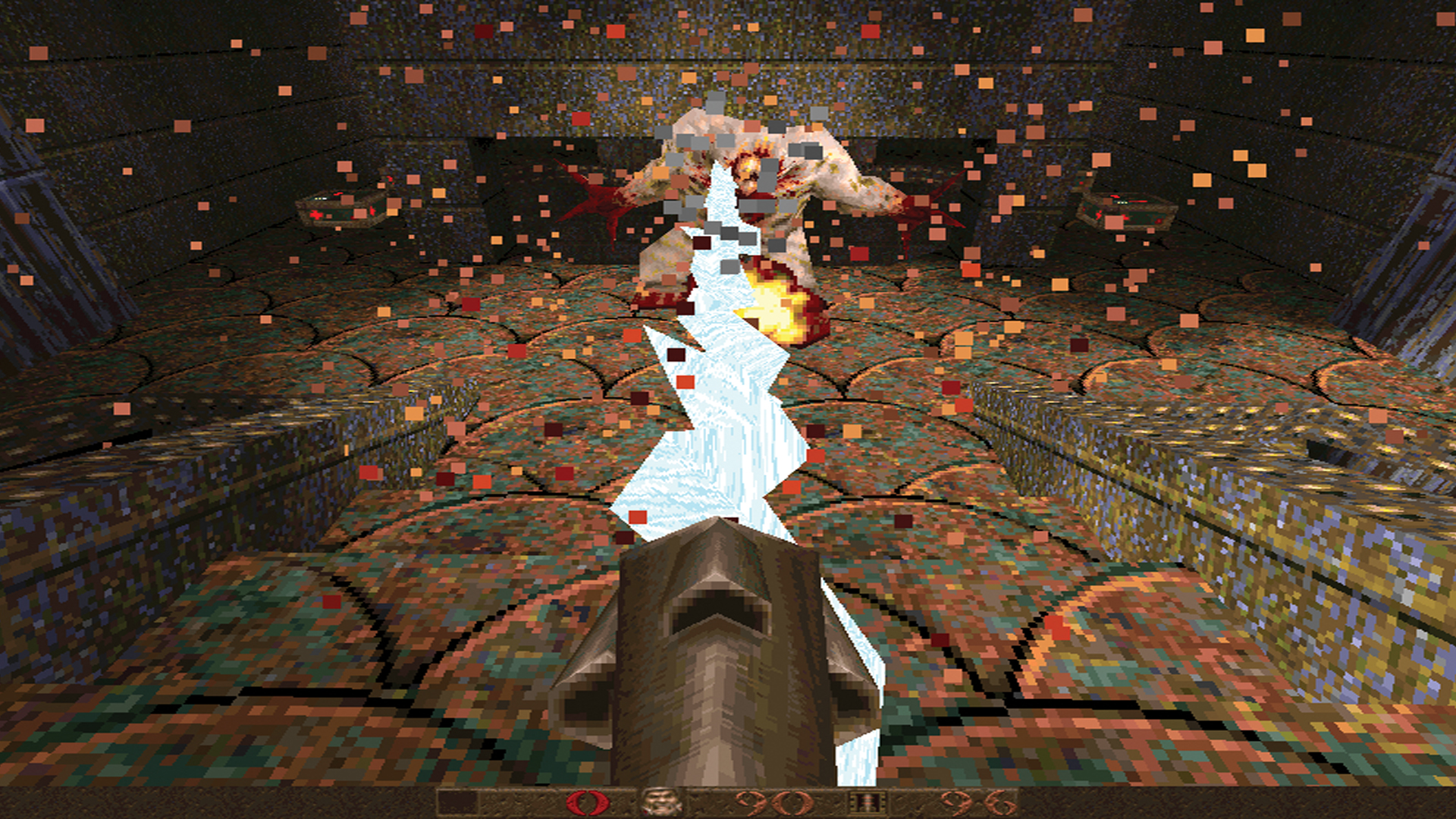

Equally cool creatures were also being created for Quake, with aesthetics inspired by the macabre imagination of author H.P. Lovecraft, including a living thunderstorm that id dubbed the shambler. "We likened it to an arch-vile in Doom," Romero continues. "He was basically a really tough monster in the first episode – the real boss was Chthon at the end. The shambler was still really tough in the other episodes, but we gave him away in the first episode, not as a boss but as a mini-boss. We gave the player the shambler to go against because maybe they would think that it was the boss, but then we really showed them what a boss was in Chthon."

"I had a rule for the designers that if they created a room in Quake and it could be replicated in Doom then they had failed"

John Romero

One of the most obvious outcomes of Quake's vertical level design came in the form of platforming challenges, which Romero and his team integrated into their game's core objectives of continually powering-up and completing levels by finding their exits. "Even on the very first level, you got into a dark room where you were coming down ramps, and there was one hundred health up there. the only way to get it was to do some crazy platform-hopping," Romero says of an early vertical challenge in Quake.

"There were little pegs sticking out of the walls, and if you could jump from peg to peg and get all the way up there you could get the health. There was another level with a room that had these pieces of stone that came out of the wall that you had to jump up the sides of the wall on. It was like going up stairs, but you had to platform jump to get up and out of the room."

More sophisticated platforming standards followed as the Quake team implemented impressive set pieces spanning everything from retracting drawbridges to deadly elevators. "One of the things that we got to do in Quake was take the player on a ride," says Romero. "So they could walk onto a platform and it would just start moving. One thing that I did was take them in an elevator. When they pressed the button they were locked in, it started going down and it took them underwater, and all of a sudden they started dying. It was perfectly timed for them to come up out of the water at the end and pick up health, but they were panicking the whole time because they didn't know what was going to happen!"

Romero's elevator ride was far from Quake's only use of an underwater environment; in fact, the Quake team filled their game with sub-aquatic challenges. These favoured gameplay over realism and allowed players to be as trigger-happy underwater as on land. "The only limitation was that if you had the Lightning Gun underwater you were dead if you used it – unless you were invulnerable," he says. "Gameplay was totally a priority. The only difference was that you moved a little slower than on land. But no one would have wanted to go in the water if we had lessened their ability to shoot the weapons. So it made it way more fun to be able to just do what you did on land."

This thinking also followed through to Quake's hidden areas and levels, which were as likely to be found at the bottom of murky lakes as in equally obscure above-water locations. "Putting secret areas in the game made it replayable," argues Romero. "It made it so players would search all over the place and spend more time on the levels, which would help them understand them more. Typically, we hid the next most powerful weapon in a secret area so that you could get it early. There was also an exit to a whole secret level somewhere, and if you could find that exit then you had found an entire level of cool stuff."

Creature comforts

Best Year in Gaming 1996: the year video games were entrenched as the future of entertainment

Given the threat posed by Chthon, not to mention Quake's other nightmarish bosses, it must have been tempting to demand legendary firefights of players in order to defeat them but, as with previous design decisions, Romero chose innovation over expectation. "Chthon was unlike any boss that we'd had in any of our games," he says. "He was a huge lava creature that you couldn't just shoot to death, you know, you had to actually use lightning against him. so you were using the environment against the boss. Shub-Niggurath was the ultimate 'how do i kill that thing?', which you did just by paying attention to the environment and what was going on, and trying to figure out how you would kill him."

Unlike Quake's bosses, the game's less challenging opponents could be shot to death, although the weapons Romero's team designed for their game included a couple of particularly visceral bullet-free options. "The nail-gun was one of the first weapons that we created," Romero reveals. "We hadn't seen one in a game, and we were joking around that it would be hilarious to just shoot nails at people! The axe was basically because in the first design you were going to be hatcheting characters. So the axe was a holdover from the medieval design, and the nail-gun was a holdover from the experimentation during the medieval phase."

An equally gruesome but more elemental instrument of death followed, as Quake's medieval origins prompted Romero to dream up a gun that fired bolts of lightning. "I thought it was different and powerful because of the way that you could hold people up in the air with it," he continues, "and you could use it really fast. The really cool thing for me was how it could be like a BFG as well. I thought: 'Well, if it affects everyone in the room, what if you jump in the water and discharge and that blows up everyone in the water?' We didn't have anything like that, and it felt like a really good way to make a multi-function weapon."

In order to compliment Quake's imaginative set of weapons, Romero and his design team also devised a range of power-ups, including one to enhance the weaponry that subsequently became synonymous with Quake thanks to the arrival of the game's box-art. "Originally, it was just going to be a rune that had 4X on it," he says. "It gave you whatever your weapon's damage was times-four for 30 seconds, and that was it. Then when we got the Quake logo it obviously had to be 'Quad Damage' because of the 'Q.' So we made that model. The Quad was like: 'What if we could do the Berserk from Doom, but on everything?' With Doom, you picked up the Berserk pack, and from the time you picked it up until you were dead your fist would destroy stuff. So my thought was: 'What if you could pick up something that gave you crazy amounts of power like the Berserk for every weapon you had, but on a 30-second timer?'"

Tearing id apart

"I'm super proud of Quake; I think it's a great game. It's just too bad that it tore id apart because it was so hard to make"

John Romero

In the months following id's final changes to Quake, the game released to positive reviews that only fell slightly short of the dizzy expectations created by the pre-release buzz that had surrounded the game. Quake did go on to sell in its millions, however, regardless of the critical response, although Romero stuck to his decision to part ways with id Software, and so didn't see a penny of profit for his work on the title.

"I knew the game was going to do really well," says Romero. "For a whole year before it came out, there were articles all over the place and magazine covers – everyone was waiting for Quake. People knew it was going to be the next thing. So it was great to have that kind of hype. When it came out and everybody was playing it, it was great for me because I was putting together a new company, and you always want to have a success when you're trying to do that. The negatives were that I didn't actually get any money from Quake because I was gone, but the positives were that I got to leave after making a really successful game."

John Romero remains equally philosophical about his last, and arguably greatest, id FPS when asked for his thoughts on Quake now, although the fact that the developer's hopes for the game were repeatedly scaled back is still a matter of some regret, as is the knowledge that Quake was essentially responsible for breaking up the original id team. "I would have had a more cohesive design and spent more time during 1995 getting a design down that was more solid and could have improved upon the FPS instead of just making another FPS," Romero admits. "It also really needed to have better weapon balance, with more focus on the weak weapons. But I'm super proud of Quake; I think it's a great game. It's just too bad that it tore id apart because it was so hard to make. After Quake, within six months of its release, half the company was gone."

Rory is a long-time contributor to Retro Gamer Magazine, and has contributed to the publication for over 10 years. He also contributed to GamesTM magazine, and once interviewed Hunt Emerson.