Skyrim on Switch is a marvel, but Oblivion made the Elder Scrolls series what it is today

Oblivion's blend of idyllic normality, fantastical drama, living AI and a ludicrously detailed skill system set standards for a genre, and an entire industry.

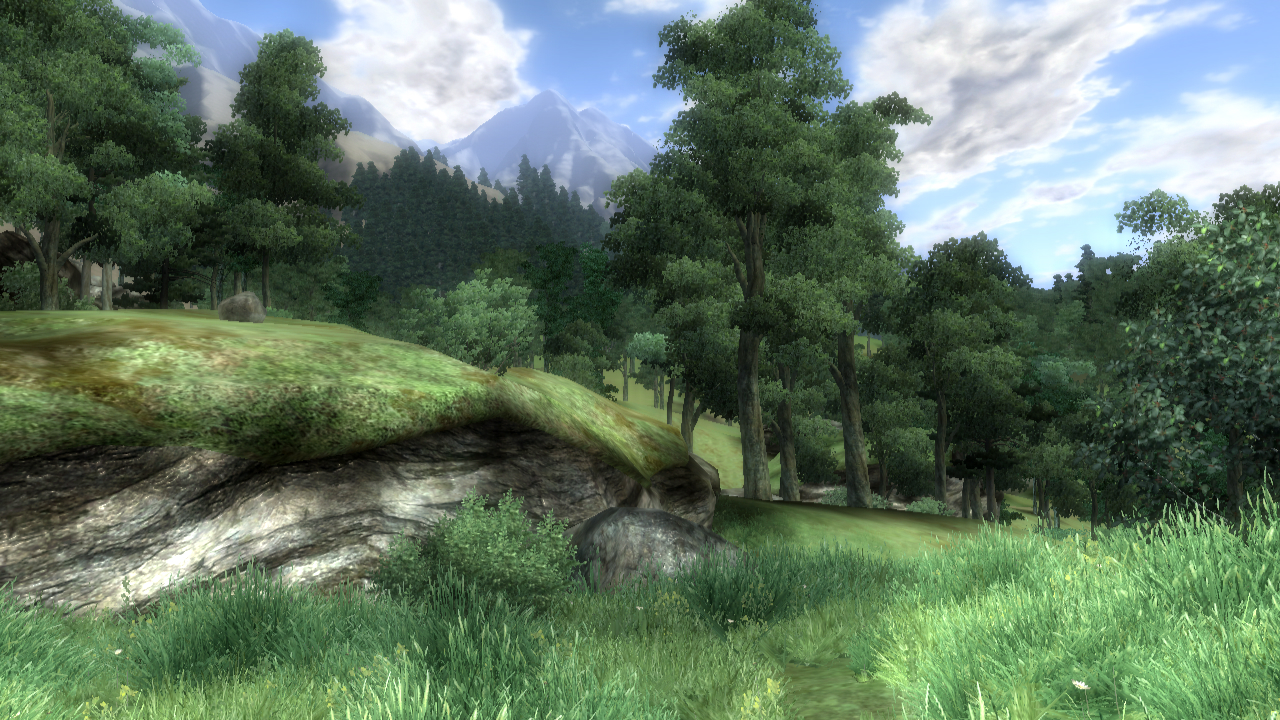

Tamriel, the continent in which Elder Scrolls quests take place, is a diverse and improbable land: tales tell of migratory tree cities in dark Valenwood, impenetrable swamps and assassins in Black Marsh, and supremacist uprisings on the Summerset Isles. Released between Morrowind, a volcanic land of warring elf houses, and Skyrim, an untamed Nordic wilderness, The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion seems positively mundane. The Imperial heartland of Cyrodiil in which it’s set could be confused for Yorkshire.

You’re spat out of a sewer pipe onto the Imperial Isle at the start of the game. Ahead of you is a crumbled old castle – replete with bandits, naturally. Above are birches and elms, and across a placid river lie miles of rolling farmland. At its most exotic, far to the northwest, Cyrodiil begins to resemble the New Forest: a little sandier than the rest, with the occasional rock of note.

This was Bethesda’s first experiment with procedural generation, which producer Gavin Carter would promote with the unflattering statement that the studio could “churn out realistic environments much more quickly and efficiently than we could in Morrowind.” Cyrodiil’s enormous landmass was the product of 50 people and an algorithm ten years before the likes of No Man’s Sky were creating worlds of impossible variation at the press of a button. Vegetation got the procedural treatment, too – new plants and rough forests could be spawned within minutes.

It’s hard to say what came first: the choice of setting or Bethesda’s new tech. Hills and plains were more forgiving to early procedural algorithms than crags, ravines and volcanoes. Modders would step in to give the landscape some spice, introducing gorges and redwood forests to break up the unsullied rural views, but the bulk of Cyrodiil would always be reserved, safe and respectable. It was in stark contrast to the demon-slaying action Bethesda liked to focus on in its trailers.

An everyday setting with wondrous consequences

This quintessential Britishness – the unassuming familiarity of creeks and pastures – is the basis for Oblivion’s strength as an RPG. By immersing you in the everyday, the extraordinary had more impact than in Skyrim’s land of dragons or Morrowind’s alien landscape. It’s a hallmark of British fiction to take a mundane scene and appal, surprise or amuse us (often when we ought not to be amused), and your misadventures in this placid world had the loud ring of MR James or Neil Gaiman. By accident or design, Bethesda’s Maryland team created an exquisitely British game.

Walking along the quaint country road to Cheydinhal, you’re struck by the peace of it all: heather swaying gently, woodland rolling off into morning mist. To the left, you might notice a short flight of wooden steps mantling a hill, upon which sits a small grotto. There’s even a veranda of sorts, sporting a pair of barrels and nothing else. It’s the kind of place to while away time just sitting on a Sunday afternoon. Pop inside the cave, however, and odds are good on you contracting porphyric haemophilia. You will soon become a vampire.

Or perhaps, wandering the deep forests south of Chorrol, you might come across Hackdirt. It’s a self-contained settlement reminiscent of Cotswold hamlets, with chapel, town square and a few dwellings. The people are rude, but that’s country folk for you. Or maybe not – spend more than a day or so in town and rudeness will escalate to aggression. Investigate the source of their hostility, and you’ll find yourself plunged into a Lovecraftian nightmare.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

This isn’t to give unbridled praise to a procedural landscape, though. Sometimes the countryside became samey and empty – it was often monotony that made finding an unexpected quest a delight by contrast, and many of Bethesda’s grander ambitions never made the final cut. Take the much-lauded Radiant AI, the star of Oblivion’s E3 in 2005. This was the system that was supposed to give life to Cyrodiil unlike any seen in an RPG. To an extent it worked: NPCs had a daily routine that they would follow until something else took precedence. They would meet and talk to each other, even if those conversations seemed to concern nothing but mud crabs.

By comparison, Morrowind’s NPCs would stand in the same spot waiting to dispense a quest or some vital dialogue. But the complex behaviours touted in pre-release presentations, such as an NPC realising its inadequacy at target practice and heading off to buy a marksman potion, never materialised. The official ‘making of’ documentary features an anecdote about the early days of Radiant in which one NPC bought every piece of armour in the city, driven by some crazed concern for his safety. In another example, by the time players encountered the local skooma dealer he would always be dead – NPC demand for the good stuff was so high that they were willing to kill him to get their hit. These behaviours weren’t so much fixed as sanitised.

Elsewhere, Oblivion was rougher. The skill system was a hodgepodge of stats, major skills and minor skills that were so minor as to include Athletics and Acrobatics – or running and jumping. You could become a master acrobat by standing on a table and spamming jump (the ceiling curtailed the jump animation but not the XP gain; Cirque du Soleil would weep). Perks, awarded at milestones within each skill, were similarly flawed: a master in the Heavy Armour skill, for example, suffers no encumbrance from all the Daedric steel they lug about, making light armour redundant.

An RPG purity never bettered

However rickety the skill system was, its unwieldy sprawl spoke to a game secure in its identity as an RPG – something Bethesda has wrestled with since. During the introduction, you could design your own class from scratch, if you chose, and the useful options extended to five separate schools of magic, bladed and blunt weapons, hand-to-hand combat and more. Playing a stealthy marksman with a splash of Illusion magic on the side was a wildly different experience to a stealthy marksman who could conjure familiars. Choosing your major skills meant letting something vital lag behind for many hours. Here, it was much harder to become a Swiss army knife than it was with Skyrim’s perk-centric levelling pathways or Fallout 4’s wholly perk-based experience, which feels like it would frankly rather not be there at all.

It’s hard to give Bethesda full credit for the understated, disruptive tone that resulted from Oblivion’s familiar world and nods to RPG tradition when the main story conflicts so keenly with the self-restraint elsewhere. Morrowind threw you into the middle of a near-incomprehensible political tangle. You were predestined to resolve it, obviously, but that didn’t make events easy or even especially important. Its main quest often sent you on sabbatical to get more levels and adventure under your belt – kicking back with perennial distractions such as the Fighters Guild was sanctioned by the story. Oblivion was dozy and idyllic, but your main objective – imparted by none other than bombast king Sir Patrick Stewart as Emperor Uriel Septim VII – insisted that you save the world quick smart.

From the off, the Emperor is slain, a city destroyed and a bored-sounding Sean Bean rescued as portals to Hell begin springing up across the country. However, this was still a game that allowed you to go and do whatever you pleased, so while your quest log read something like Nostradamus on downers, you were off picking mushrooms in the cave of Goblin Jim (a human, it’s revealed – what laughs were had). You wanted to be investigating neighbours for a paranoid wood elf in Skingrad, but the story wanted you dungeon crawling through repetitious demonic planes.

Bizarrely, the decision to set the player’s objective out of pace with the laidback, expansive world has persisted in every Bethesda adventure released since. In Skyrim, you’re meant to be defeating the harbinger of Armageddon, but you’d rather be stealing everyone’s cutlery. In Fallout 4, your son has been kidnapped and your wife shot dead – what better time to build a scrap fortress on top of a fuel station?

In light of Bethesda games’ recurring issues, it’s easy to forget that Oblivion was an innovator. Bethesda now sticks to its formula so closely that it hardly seems possible that it once set genre standards. What triple-A fantasy RPG these days would launch without daily routines for its NPCs? And surely nothing but nostalgic throwbacks such as Pillars Of Eternity could get away without fully voiced dialogue with a few impressive thespian names on board. NPCs were universally potato-faced, and the distant level of detail was so low as to make faraway hills look finger-painted, but Oblivion was unprecedented in its scale and technological ambition.

The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion launched just months after the arrival of Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3. Its size and beauty were ample advertisement for the power of the new generation; its relentless high-stakes story in keeping with the growing public love of action, if not its own world. But the limitations of its new procedural generation tech and the presence of a fulsome RPG skill system forced Oblivion into a peculiar middle ground characterised – outside of the main story, at least – by restraint and emptiness, punctuated by disruptive intrigue. Its sleepy fields, forests and villages are inherently relatable, lulling you into character. When it suddenly turns black – when you’re finding the corpses of Mages Guild initiates in the depths of a well, say – the drama and heroics that result feel more real than anything that Bethesda has done since.

This article originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more great coverage, you can subscribe here.