Captain America dials in on "the challenges of being a hero in a world that needs so much fixing" with Marvels Snapshot

Writer Mark Russell explains his view on the 'world outside your window.'

Marvel Comics is 'the world outside your window' – or so the old adage goes, though the publisher is usually given to center its stories on the superheroes that populate their universe. But Kurt Busiek and Alex Ross's Marvels goes the other route, placing a specific focus on the human point of view in the Marvel Universe through the lens of "regular people". That point of view, established in the original 1994 limited series now informs a series of one-shots titled Snapshots which dial in on what happens when Marvel heroes seemingly beat the bad guy and leave the scene.

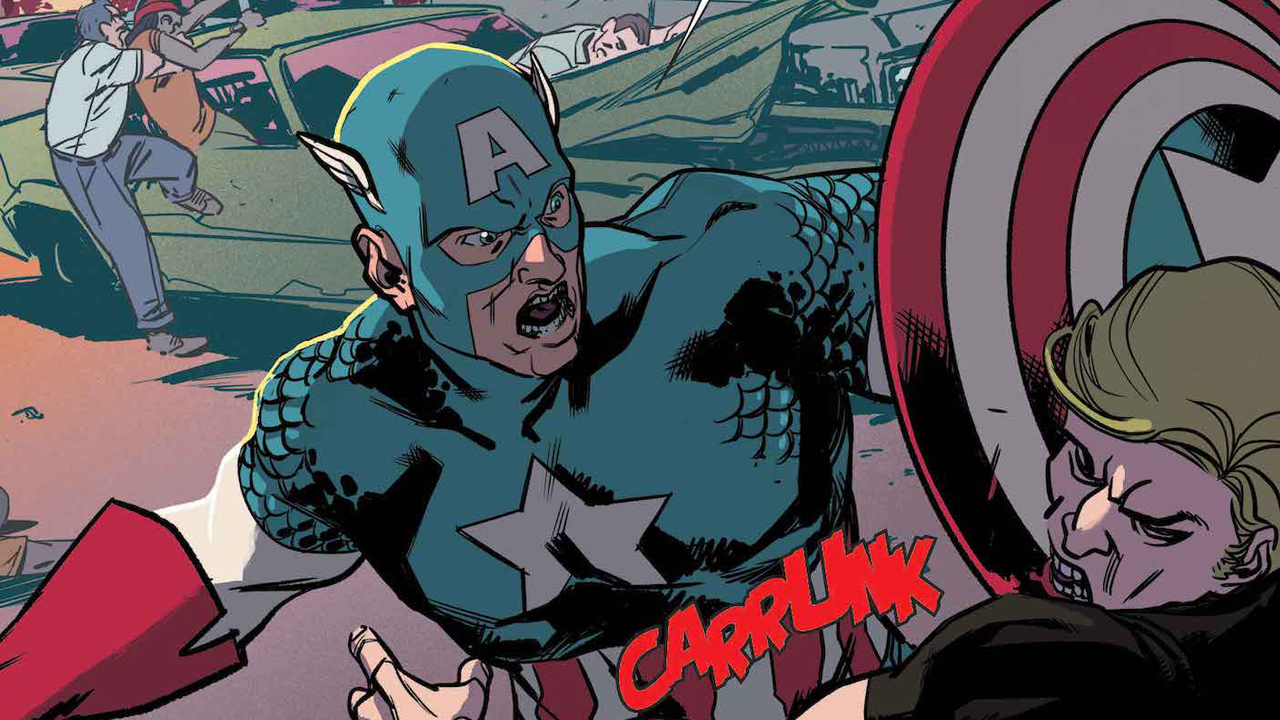

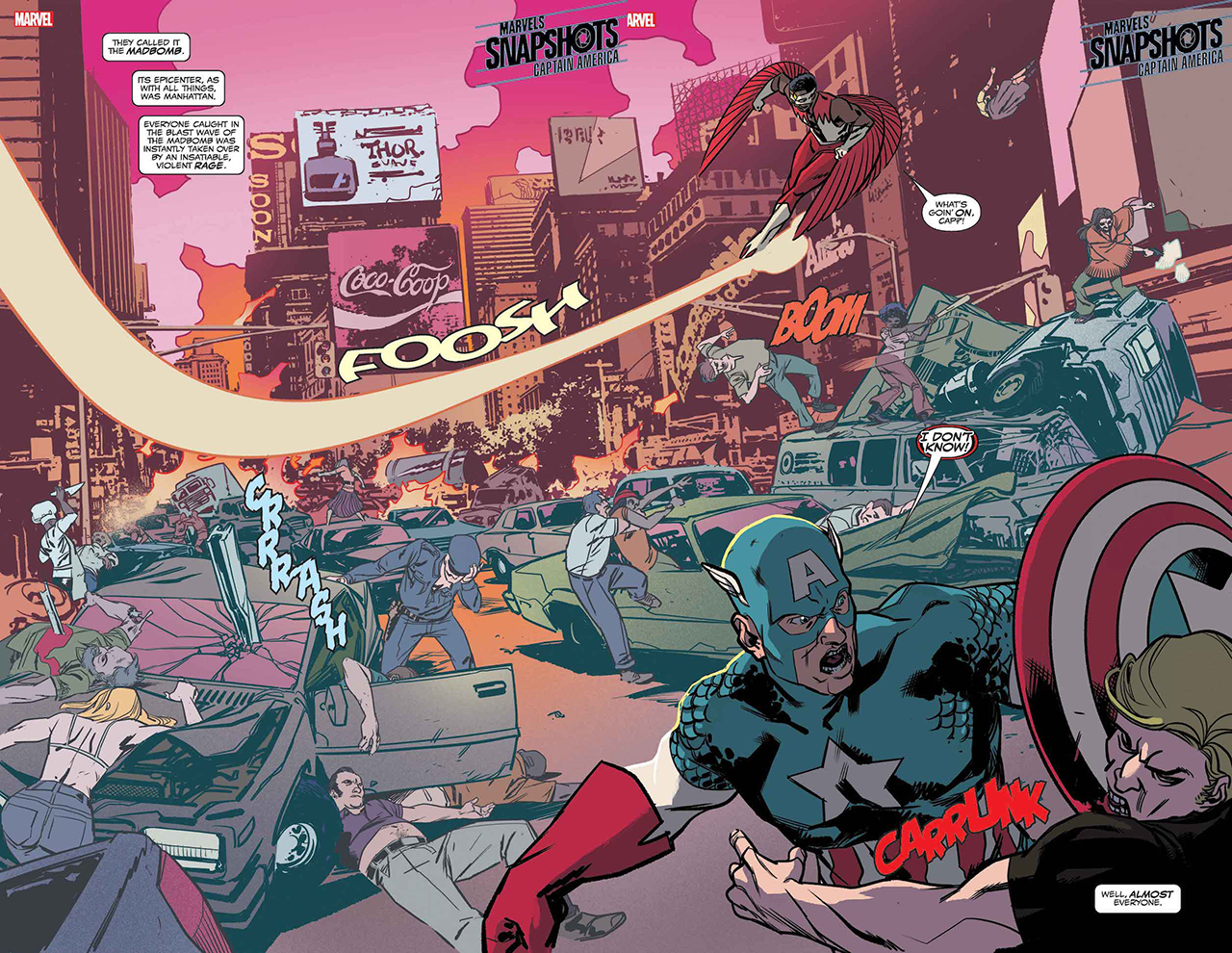

With Marvels: Snapshots now returning on June 24 after an industry-wide publishing hiatus due to COVID-19, writer Mark Russell is telling the tale of what happened after a classic Captain America story, Jack Kirby's Madbomb, with artist Ramon K. Pérez.

Though written and originally intended for publication months ago, Russell's own words on the theme in his story – "how you can only neglect other people's problems for so long until they become your own " - seem almost prophetic given the current sociopolitical climate of the United States when he elaborates on it.

Speaking to Newsarama ahead of Marvels Snapshot: Captain America #1, Russell dialed in on that theme, on how the concept of following Jack Kirby's Madbomb came around, and how this tale relates to the overall Marvels and Captain America mythos.

Newsarama: Mark, this Marvels Snapshot shows the aftermath of a classic Captain America story - The Madbomb, by Jack Kirby. What’s the tale being told here?

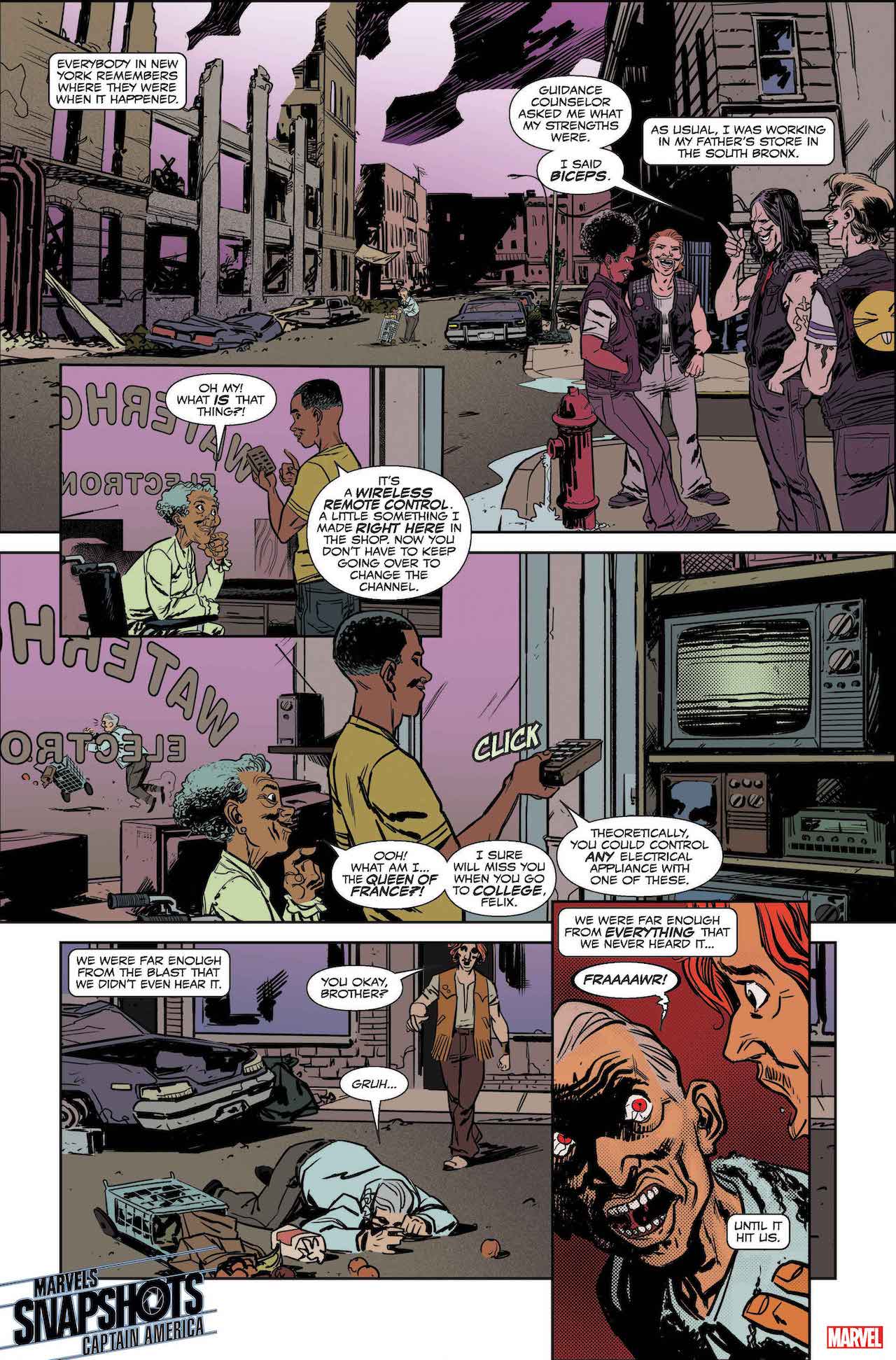

Mark Russell: It tells the story of the aftermath of the Madbomb and, in particular, about one kid in the South Bronx who tries to rebuild after the Madbomb destroyed his neighborhood and killed his brother. It's largely based on how the South Bronx was abandoned in the mid-70s, how it became easier for landlords to arson their own buildings than make them habitable, for the police to respond occasionally to riots than actually protect the people who lived there.

It's really about how you can only neglect other people's problems for so long until they become your own. Which seems like a lesson we never fully learn.

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

Nrama: Marvels Snapshots are about reframing big Marvel moments from another point of view - what’s the PoV we’re getting here? How did that ethos inform your story?

Russell: The point of view here is from Felix Waterhouse, a sort of electronics wunderkind who watches as the rest of New York is rebuilt after the Madbomb except for his neighborhood, which is mostly poor and black.

He's a very introspective young man and he tells his story and his thoughts about what's happening almost as if in a diary. He tells, not only his own story, but that of his family and his neighborhood and how people internalize guilt for their own victimhood and how this is the real "madbomb" we simply expect people to live with.

Nrama: What made you want to tell this specific story?

Russell: Kurt Busiek approached me with the idea of writing a Snapshots story set in the aftermath of the Madbomb, which was written and took place in 1975. He also had a general idea for a story involving a kid who wanted to go to college but couldn't because of the Madbomb. This was a more than generous starting point for me.

When writing a story set in a specific time and place, I like to think about what is going on in the world at that time and how it relates to what the world is going through now. So, for me, it just seemed natural to set the story against the backdrop of the Burning Bronx, which was going on at the same time as the Madbomb and seems to be a relevant analogy for how we prefer to prefer to profit off people's misery than fund the services that make our cities livable.

Nrama: Political and social allegory is one of the hallmarks of your work. What are themes and metaphors you’re drawing on here?

Russell: I suppose the big one is that we do not exist in isolation. That when institutions ignore the people they're supposed to serve, it's only natural for people to find a way to make themselves impossible to ignore. Which I believe we're seeing now in no uncertain terms.

Nrama: As you mentioned, you worked alongside Kurt Busiek and Alex Ross, the original Marvels creative team, for this story. What was that process like?

Russell: Kurt was a great collaborator. The process was mostly us talking on the phone, me sending him a script, and then him calling back to tell me what I did wrong.

I thought I knew how to write a comic book script before, but working with Kurt sort of disabuses you of that illusion. He has great instincts for what works and what doesn't. And he’s super knowledgeable about the minutiae, the little but important details that go into making a comic.

One time, he called me to tell me to take all the punctuation out of my sound effects. "They're not actually words," he explained. "They're sounds. They don't need punctuation."

Maybe this is the sort of thing everyone in comics knew except for me, but my mind was blown. A lot of times, we'd talk on the phone for about ten or fifteen minutes about the script and then for an hour about comics and our own weird writing philosophies. Whatever else comes of this series, I will always treasure those conversations.

Nrama: On that note, you’ve got Ramon Perez drawing this one-shot in his classically informed comic style. What makes him the perfect collaborator for this story?

Russell: For me, the thing that really drew me to Ramon was how well he handled the human emotion of the scenes. It's one thing to handle the super hero action scenes and the bizarre Kirby-tech, all of which he does well, but what really makes a story work is the emotional resonance of the characters. What we can tell from what's going on inside them from a simple glance or a lowered head. Especially in a story like this that is told mostly as the internal monologue of one character, handling his emotions and his sense of loss was really key to the art. And Ramon just really nailed that.

Nrama: What are the principles you’re keeping in mind to get an idea across in a single issue versus going into a longer series?

Russell: In a one-shot like this, everything has to be immediate. Don't save anything up. Spill your guts on the page while you have them. If you set something up in the first half of the story, it better have a reason for being there. If you're not going to move a piece, it shouldn't be on the board. Space is precious in a single issue, so save every panel for things that matter.

Nrama: Bottom line, what can readers expect from this one of a kind Captain America story?

Russell: I hope they'll find a thoughtful story about what heroism means in the real world. One of the challenging aspects of this story was to write a Captain America story in which Captain America isn't really the main character. But, in taking a back seat, it gives Cap a chance to be a little more vulnerable than usual. To be more man than hero, to listen to what others need from Captain America, and to address the challenges of being a hero in a world that needs so much fixing.

I've been Newsarama's resident Marvel Comics expert and general comic book historian since 2011. I've also been the on-site reporter at most major comic conventions such as Comic-Con International: San Diego, New York Comic Con, and C2E2. Outside of comic journalism, I am the artist of many weird pictures, and the guitarist of many heavy riffs. (They/Them)