Phoenix Point turns XCOM into a terrifying simulation of a climate crisis

A new twist on turn-based tactics comes from the most unlikely of places

When the UK's prime minister didn't turn up for a televised climate debate before Christmas, the producers gave his seat to an ice sculpture. Boris Johnson was replaced by a depiction of Planet Earth, melting under the studio lights while party leaders battled to prove they cared enough to save it. The symbol was potent enough that the government threatened to review the TV channel's broadcast license in retaliation. And I can't help but think of it when I play Phoenix Point – a game that sticks the globe right up in your face and asks you to watch it deteriorate.

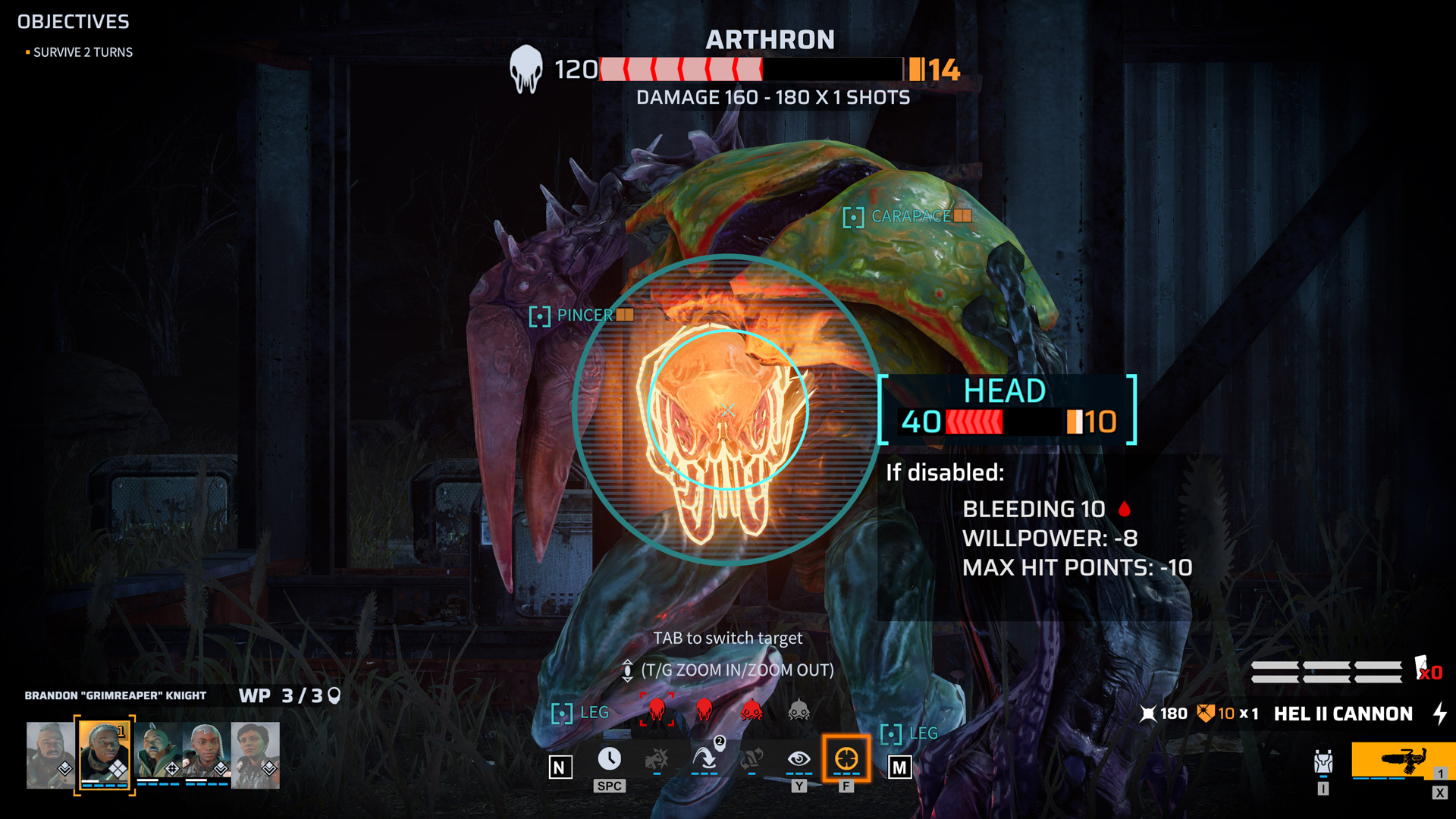

Phoenix Point isn't explicitly about climate change – rather it has a pulpy science fiction premise. This is a game that belongs to the same genre as XCOM, and replaces the alien enemy with Pandorans – crabmen covered in enough crustaceans to keep the seafood restaurants running long after the last government falls.

Yet the sea rising up to reclaim the planet from its irresponsible human occupants is an eerily familiar concept. A report from America's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, compiled by around 450 scientists, found that 93% of heat energy trapped by greenhouse gases winds up in the ocean. That heat accelerates the melting of glaciers and pushes sea levels to extreme highs. In Phoenix Point, the in-game threat is represented by a spreading mist that heralds Pandoran attacks, but the effects are strikingly similar: huge damage to cities and the mass displacement of people living in coastal areas.

Pushing back a tangible manifestation of climate change might have been, by itself, a satisfying enough prospect to fuel Phoenix Point. Think of the Godzilla and zombie movies that helped previous generations process the ever-present threat of nuclear annihilation. It suits our terror-lashed brains, built for problem-solving, to imagine a world in which we might learn to navigate or conquer a threat of extraordinary magnitude. But Phoenix Point goes beyond that simple purpose to model something much more complicated: the myriad ways humankind reacts to existential menace. It simulates denial, squabbling, self-reckoning and faith.

One World

Snapshot Games breaks from XCOM tradition by depicting humanity not as nations broadly united in Earth's defence, but as a set of factionalised survivors huddled in walled cities. These factions represent divergent opinions on how to tackle the Pandoran invasion, or whether it should be tackled at all. Even when you're not interacting with them, their lives play out in the background – they build economies, conduct research, and fight to keep their coastal outposts standing.

The Phoenix Project is scrappy at best, and you're compelled by your precarious position to engage other groups in diplomatic relations. Before long, they're publicly denouncing each other and asking you where you stand. The most familiar position is that of New Jericho, the faction founded by a billionaire CEO of the old world, Tobias West.

"Pushing back a tangible manifestation of climate change might have been, by itself, a satisfying enough prospect to fuel Phoenix Point"

There's an obvious comfort in looking to the most successful people on Earth to save it. If they pulled it off, we'd be partially redeemed for rewarding just 26 people with as much material wealth as the poorest half of the world put together. Wouldn't it be wonderful if Elon Musk's batteries became the answer to climate emergency? We wouldn't have to fundamentally change how we live. We'd get to keep our cars, and our consoles.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

But, as Tesla's shareholders have discovered, the risk of a cult of personality is the personality at the centre of it. Like Musk, Tobias West has a weakness for flamethrowers and controversial pronouncements. By midway through my campaign in Phoenix Project, West was at war with everybody. It's possible to lift New Jericho to ultimate victory, but only by softening some of the blows West has inflicted on himself. If the game takes a position on the super rich in a climate emergency, it's that they need us as much as we need them.

Factions at war

Theists are represented by the Disciples of Anu, who embrace the spreading mist as both a punishment for humanity's hubris and a test that will see it reach new heights, a la Noah's Ark. They've discovered one weird trick that lets them take on mutations without losing their sentience – Tobias West hates them!

Then there are those who view climate change – sorry, the Pandoravirus – as an opportunity to scrap the deeply flawed systems that led us to it. The people of Synedrion reject market rule and the private ownership of basic resources. What particularly speaks to me is their distaste for hierarchy, and the way it extends to the environment.

The Polyphonic Tendency, a political party within Synedrion, believes that humanity has to accept a newly humble position on the planet. That means respecting the global ecology, rather than dominating it, no matter how weird it might have got. Hence their mist repellers, which keep the Pandorans at bay without destroying them. The galaxy brain moment is realising the crabmen might have as much right to exist as you do.

You start Phoenix Point with practical concerns, like where your next landing craft is going to come from, or whether New Jericho can be persuaded to share their really big guns. But before long, it's clear the game wants you to hash out a philosophical position. Play the game for long enough and you might just work out how you feel about climate change. As mechanically traditional as it undoubtedly is, Phoenix Point has made the old XCOM formula all too relevant.

Looking for more on the way that games reflect the problems we face on Planet Earth? Here's an exploration of why video games are better at recognising the dangers of climate change than politicians.

Jeremy is a freelance editor and writer with a decade’s experience across publications like GamesRadar, Rock Paper Shotgun, PC Gamer and Edge. He specialises in features and interviews, and gets a special kick out of meeting the word count exactly. He missed the golden age of magazines, so is making up for lost time while maintaining a healthy modern guilt over the paper waste. Jeremy was once told off by the director of Dishonored 2 for not having played Dishonored 2, an error he has since corrected.