Myth in games

The timeless origins of 10 gaming tropes

Basically, they’re both out to get you.

Most games are about Good and Evil, right? Yes and no. Since Asteroids and Robotron, designers have been dumping the player into a Chaotic shitstorm and forcing them to lay down heavy-artillery Order. As games develop increasingly sophisticated morals, characters like Niko Bellic and FFXII’s Ashe are increasingly asked to choose between an Order that doesn’t feel right and a Chaos that doesn’t bear thinking about…

Hallmarks:

- Orders take their design cues from Blade Runner, the Renaissance and Nazi Germany.

- Chaos tends to look like a direct-to-video HR Giger, Guillermo del Toro or a ‘90s serial killer flick.

- Either way, someone’s going to end up making an interminable speech.

Above: Yes, but why don’t you shut up?

Some Examples:

The DOW vs the Firstborn (Clive Barker’s Jericho), JC Denton vs Majestic 12 (Deus Ex), You vs Everyone Else (Smash TV).

Where’s This Come From, Then?

The Gnostics of early Christianity, influenced by Classical mythology, suggested a world of imperfect Order corrupted by Chaos. Later thinkers like Nietzsche and Marx revived the debate with pointed questioning of all of civilisation’s structures. This dichotomy of human thought reached full fruition when Condemned: Criminal Origins allowed you to bash homeless people in the face with a 2x4.

How Do Games Do It?

The nerd community (many of whom may be gamers) doesn’t have a lot of love for societal order, so plenty of games (Hitman, Final Fantasy IV) see the heroes rebel against a corrupt Establishment. But the motif can also be seen in Resident Evil’s viral outbreaks or BioShock’s Rapture, whose Objectivist creed sent amateur philosophers all into a tizzy.

The Trickster

Also known as the “Fan Favourite.”

The Trickster is in it for Number One, and will help whoever best serves their ends. Instead of muscle, this showy type uses inventiveness and deception to confound their enemies. Whether enemy, ally or protagonist, The Trickster is in the game to challenge players to stretch their brain-muscles.

Hallmarks:

- A tendency toward the theatrical.

- A penchant for gimmicks (playing cards, hula-hoops, miscellaneous circus crap).

- Most likely to be “creatively” interpreted in Deviantart galleries.

Some Examples:

Mr. Riddick, Mr. Kratos, Mr. Cait Sith (boo hiss).

Where’s This Come From, Then?

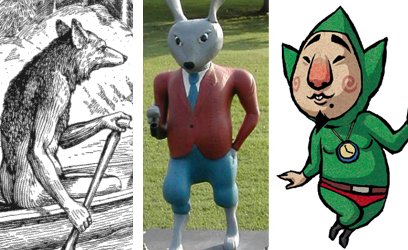

While the Trickster is often shown as dark and distrustful in Western tales – Loki, Shylock and much-maligned Pan – world myths showcase the character’s clownish side. Brer Anansi, Hermes, and Monkey showcase the playful bravado that has garnered the Trickster their treasured place in storytelling.

How Do Games Do It?

Early games boasted no end of playful Tricksters. That innocent notion was put to death about the time this giggling wanker showed up:

Above: The jeers of a clown

Around this time, comic books had a thing called a “dark anti-hero” that was going off like gangbusters. Games were inspired! Thus commenced an age of selfish jerks without even the decency to come out for an honest brawl.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Above: Oh, man up

Modern games are finally starting to get their heads around the potential of the Trickster: Hideo Kojima, in particular, uses characters from the celebrated Psycho Mantis to the bewilderingly debonair Drebin to bring wryness to games that could otherwise run the risk of taking themselves too seriously.

Above: Crisis averted