Is the JRPG in danger of leaning too far into its niche?

Games such as Bravely Default 2 give fans everything they want, but don't offer much in the way of surprise

The best games give players something they didn't know they needed. But there's always a market for those that provide precisely what their target audience wants. Currently, it's the ones that try to be all things to all people that are struggling. Development on BioWare's Anthem – a game with several good ideas in dire need of a hook – has been discontinued. And the servers for Gearbox's hero shooter Battleborn (lest we forget, an "FPS; hobby-grade co-op campaign; genre-blended, multi-mode competitive e-sports; meta-growth, choice + epic Battleborn Heroes!") were switched off in January.

It pays to specialise, in other words, and that partly explains why the JRPG increasingly seems to be leaning into its niche, and is enjoying plenty of success in the process.

It's not the only reason it makes sense. The kinds of progression systems that were once the foundation stones of the genre have been cropping up in more and more mainstream games: these days, it's hard to find a popular online FPS that doesn't have some sort of RPG mechanics. So it makes sense that JRPGs might want to go back to their roots in an effort to distinguish themselves, rather than risk alienating existing fans by trying to actively appeal to a broader global audience.

Indeed, some series are enjoying their healthiest sales by celebrating their Japaneseness. Think how Yakuza originally stumbled at the first hurdle, its expensively assembled English-language voice cast mostly failing to convince (we still have a soft spot for Mark Hamill's take on Goro Majima) as members of the Tokyo underworld. Now it's bigger than it's ever been, largely by sticking to its guns – not to mention benefitting from vastly improved localisation efforts. In the past, publishers might have balked at games such as Nier: Automata and Persona 5, but their rougher, weirder edges were left intact, their uncompromised identities actively welcomed by western and Japanese players alike.

When it comes to the traditional JRPG, however, there's a risk that developers are looking too far inwards – which, in most cases, also means looking back. We'll leave Final Fantasy VII Remake out of the equation (even if, as radical a reinvention as it is, it still trades somewhat on nostalgia), but the likes of I Am Setsuna and Lost Sphear both struggled to offer anything more than prettied-up takes on well-worn ideas. Octopath Traveler fared better with its multi-stranded story structure and striking presentation – yet that, too, was a little too reliant on old-fashioned thinking, not least with its equally old-school difficulty.

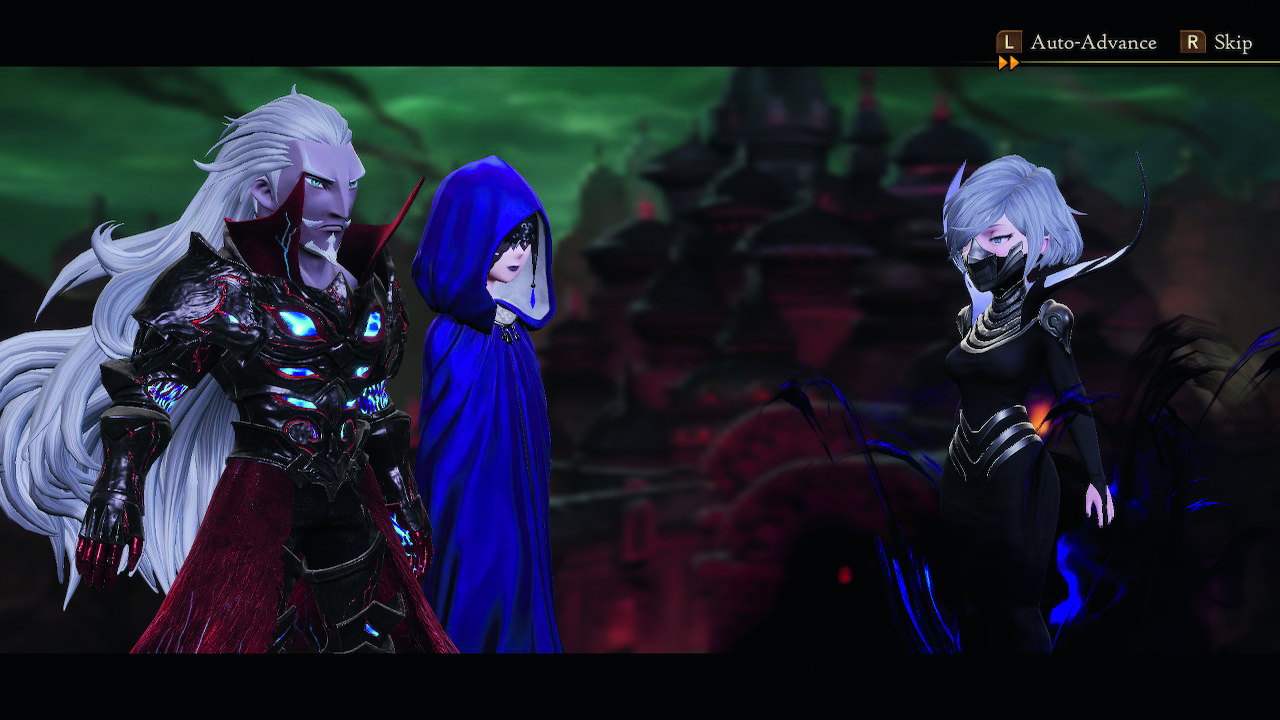

Despite the quality of its battle system, Bravely Default 2 doesn't get away with what is ostensibly a very similar approach. That's partly because any JRPG is only ever as good as its numbers game, and Claytechworks hasn't quite got its sums right.

We relish a challenge, but the bosses here are often little more than brick walls, not so much a test of what you've learned as an exam for which you discover you've been studying the wrong syllabus. But it's also because its aesthetic doesn't have Octopath's contemporary trimmings: without the accompanying lightshow, the fights lack visual flair, with that terrific battle theme doing all the dramatic heavy lifting on its own.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Still, for a certain type of player, the turn-based RPG offers comforts no other genre can provide. It's clear from the likes of Octopath Traveler – and, for that matter, the gleefully orthodox Dragon Quest 11 – that there's still an audience satisfied with the kind of nostalgic wallow that Bravely Default 2 undoubtedly delivers.

Even so, we're surely not asking too much by hoping to see more of the kind of unconventional thinking that brought us Chrono Trigger and Earthbound: era-defining games that reached beyond genre archetypes. Surely the JRPG can still embrace its unique qualities – giving us what we want, yes, but something we never knew we needed, too.

This feature first appeared in Edge magazine. For more like it, subscribe to Edge and get the magazine delivered straight to your door or to a digital device.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.