Spacer's Choice: How The Outer Worlds' Edgewater quest reveals the weaknesses of a utilitarian worldview

Warning: This feature contains major spoilers for The Outer Worlds' opening story chapter

Give me a game that offers difficult, lasting choices, and I’ll give you a player base complaining about how inconsequential those story branches really are. We hear it all the time, from Telltale’s throttled plot points to the much maligned, highly controversial ending of Mass Effect 3. Players aren’t so easily impressed with the agency they’re given by video games offering branching stories.

I’m not as harsh as some, but I tend to see their point. After playing The Outer Worlds this week, however, I was moved by how it quickly solidifies itself as one of the more nuanced, thoughtful RPGs I’ve ever played, and you don’t have to play for long to see what makes it so memorable. After touching down in the town of Edgewater on the planet Terra 2, I introduced myself to the many denizens of this nutrient-deficient, Saltuna-fed beehive.

In a world where corporations have claimed entire planets as their own in an uber-competitive capitalist society, the knowingly subpar product manufacturer Spacer’s Choice oversees operations in Edgewater, where they’ve put one Reed Tobson in charge of the town. It’s Tobson’s job to ensure everyone is working in order around the clock, and that’s exactly why a dozen workers, tired of feeling fatigued and malnourished, abandoned their posts and escaped to the wilds beyond the walls of Edgewater.

"The directive of big-picture problem solving is usually not to save everyone, but to do the most good you can."

From there, a classic RPG scenario began to unfold. Tobson needed his workers back, but the deserters have no plans to return. What was I supposed to do? At first glance, and in lesser RPGs, the decision is obvious. Side with the underdogs, the folks who flipped off their corporate overlords and ditched to the woods, where they could rewrite their own rules for how to live — maybe even thrive — and reject their winner-takes-all hellscape. But in The Outer Worlds, it’s not nearly so clean cut, and it took only a few hours before Obsidian’s game challenged my entire worldview.

If you’re unfamiliar with the concept of utilitarianism, it’s a philosophy and ethical theory which argues that the correct and moral choice in any situation is always the one that affects the most people positively. If ever you’ve toyed with the famous trolley problem, that’s a good place to start. It’s regularly a joy to play RPGs and choice-driven games with the Utilitarian worldview, and it makes some finales, like those that dovetail Life is Strange and Mass Effect 3, pretty easy to navigate. But The Outer Worlds’ first major decision point is an affront to the utilitarian school of thought, operating so fervently in greyscale it becomes nearly impossible to measure which choice benefits the most people.

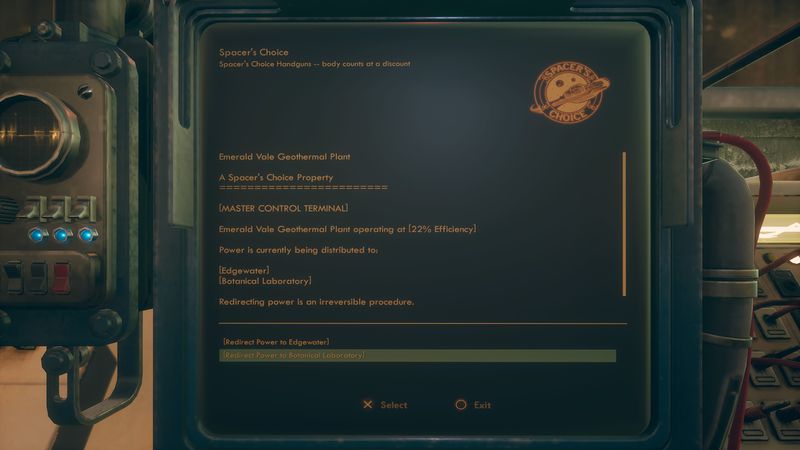

The game demands I cut off the energy supply to either the town or the deserters’ camp, because there’s no longer enough juice to go around. One may quickly side with the deserters, given their brand as righteous protestants of an unjust society. That’s all well and good, though, but there are also very few of them. Thinking in strictly numerical terms, like any good utilitarian would, the town deserves the energy, right? But how does one compare many lives of little happiness against a few lives of exponentially greater joy?

Utilitarianism doesn’t just instruct us to do what helps the most people in a mortal sense; it’s about life satisfaction too, and in that regard, the deserters are much better off. Freed from their never-ending menial jobs and eating well for the first time in years, they were content to live outside of Edgewater for the rest of their days. Does the happiness of 12 people outweigh a town of miserable drone-like workers? The decision left me frozen with choice paralysis.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

I was hopeful to learn more about each group to inform my inevitable, though oft-delayed, decision. Tobson seemed like a decent person, a hapless labourer caught up in the same machine as those who worked for him. He admitted his town’s health and safety concerns, but assured me that without the energy they needed, Edgewater would disappear completely, and then I’d have a heck of a lot more refugees on my hands. Worse, this time none of them would be living in the woods on their own terms.

The deserter’s leader, Adelaide, is a skilled gardener who managed to resuscitate the soil and provide for her band of dissenters, but takes some pleasure in watching Edgewater suffer, and that could mean doom for any future displaced townsfolk. I had hoped the game would hint to me that, should the town fall, Adelaide would embrace them with open arms and everyone would be better for it. Corporate overlords would be driven out, and a new, freer society would rise from its ashes. In reality, the game only ever seemed to suggest the opposite - that the townsfolk would be ruined without their jobs, and the little agency they still had would evaporate once the Saltuna factory was shuttered.

The Outer Worlds Edgewater or Deserters: Should you redirect power to Reed Tobson or Adelaide McDevitt?

After I had spoken to everyone, read every document, and failed to find a happy medium, there was no more room to squirm out of the inevitable decision. The questline’s final choice staring at me from my computer screen, and all I could do was stare back, even turning off the Xbox for a night and allowing myself to sleep on it, before coming back to it with a fresh pair of eyes the next day.

I chose to divert energy to the town. It felt messy and as soon as I hit the button, my choice paralysis was replaced with a sort of buyer’s remorse. The Outer Worlds is pitched as a game that takes capitalism to task, but here I was siding with Big Saltuna. Still, those townsfolk were not going to have a better life if I made them leave, and my hope was for the deserters to return to camp with the promise of a better life.

I did my best to welcome them back by convincing Tobson to step down, placing Adelaide and her green thumb into power as a successor. I envisioned an Edgewater where people were better fed and happier, even if I wasn’t the regime toppler I expected to be when I sauntered into town five hours earlier. In a moment of sobering honesty, Tobson told me he would maybe survive a week in the wild. He knew he would die soon after he was exiled, and had already begun to make peace with that. As the one determining his fate, I also had to do the same.

From the utilitarian perspective, Tobson’s fate is a reminder that the directive of big-picture problem solving is usually not to save everyone, but to do the most good you can. With that comes the stark admission that some people are sacrificed for the greater good, or are simply beyond saving. Tobson’s death was a small price to pay for a utilitarian seeking to repair a broken community, and though I still believe I ultimately did the greatest good I could in Edgewater, Obsidian made my head spin in the process of coming to that uneasy conclusion.

For more, check out the big new games of 2019 and beyond still on the way, or watch our full review of The Outer Worlds below.

Mark Delaney is a prolific copywriter and journalist. Having contributed to publications like GamesRadar+ and Official Xbox Magazine, writing news, features, reviews, and guides, he has since turned his eye to other adventures in the industry. In 2019, Mark became OpenCritic's first in-house staff writer, and in 2021 he became the guides editor over at GameSpot.