Is Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice really a successor to Dark Souls and Bloodborne, or are those comparisons a mistake?

There are blades, there is bloodshed, and there is Hidetaka Miyazaki. But does that make Sekiro a Soulsborne? Let's dig in.

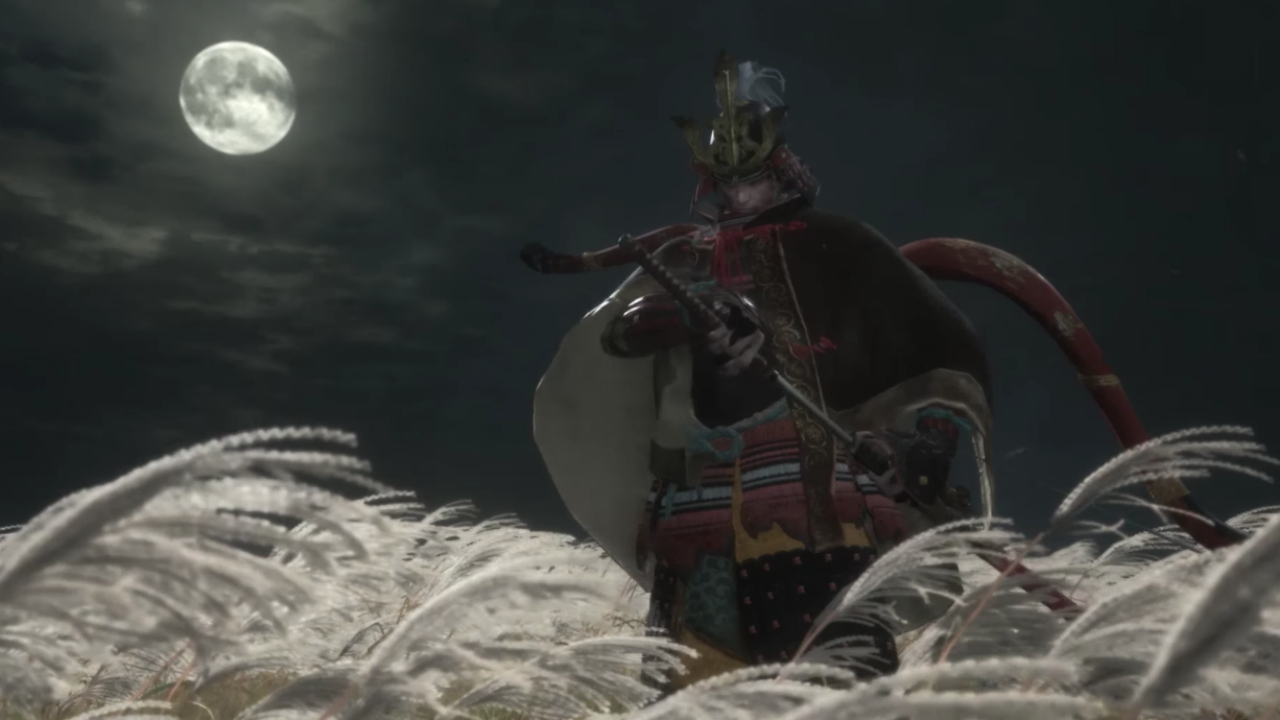

Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice is the new game from Dark Souls and Bloodborne director Hidetaka Miyazaki. Like his most recent and best-known games at From Software, it features demanding melee combat, big monsters, and an imposing, fantasy-historical setting. So, is Sekiro the next of Dark Souls’ spiritual successors? Will the path that led us from Lordran’s bleak, medieval dread to Yarnham’s eldritch, midnight horrors now take us to the blood-drenched fields of 16th century Japan? Will, in fact, Sekiro turn out to be so in-tune with From tradition as to attain the lamented but convenient-to-type label of ‘Soulsborne’? As a big fan of both series, I decided to dig in.

I’ve looked back at Sekiro’s E3 2018 demo, I’ve fine-toothed the gameplay footage, and I’ve compared and contrasted every detail of what we currently know against the intricacies of Dark Souls and Bloodborne. My conclusion: Sekiro is certainly a different game in terms of its systems, but the underpinning spirit and philosophy of Soulsborne looks entirely present, however different the body might be. Read on and I’ll break it all down, starting with the biggest point:

The core of combat: Can a swift, sword-swinging shinobi channel the methodical spirit of Souls?

Not by any means the be-all and end-all of Dark Souls and Bloodborne, but certainly the glue that holds the whole, complex experience together, combat is the first thing we tend to think about when we ponder From’s games. While things shift and evolve between games – and, more starkly, between series – a certain core ethos defines how Soulsborne combat operates. Really, it’s all about awareness.

I deliberately use that word instead of ‘difficulty’. Reason being that the ‘Dark Souls is hard lol’ encapsulation, while not inaccurate, is deeply reductive. What matters are the reasons that From games are difficult. These are games that demand focus, care, foresight, and an attentive willingness to learn, above all else. For all their harsh punishments for failure, they’re entirely fair, and present all of the answers to their stern combat challenges up front, for the observant at least. If you die – and you will – it will be because you messed up. You rushed in without understanding what you were up against, or you got impatient, or you got greedy, or you tried to brute-force a win rather than carefully carving a path to victory using insight and finesse. The most important weapons are always the player’s awareness and composure. Maintain those, and you really can handle anything.

How does Sekiro look to play into this? Really well, actually. Appearing to blend Bloodborne’s spirit of aggressive defence with Dark Souls’ focus on more immediately parseable, low-numbers encounters, the lineage is clear upon viewing just a few seconds’ footage. Dig a little deeper though, and the connections become even firmer.

The move from Souls to Bloodborne was typified by a ‘nowhere to hide’ shift away from slow-paced, defensive, reactionary play and toward the assertive aggression of more active counterattacks and pre-emptive movements. Thus, Sekiro’s emphasis on ‘push forward’ parries, knockbacks, and counter-stuns feels like a combat system evolved from Bloodborne in a similar fashion to how Bloodborne grew from Dark Souls. It’s all just the next link in the chain.

Take a look at the more nuanced means by which Sekiro crafts its combat flow. The overarching system governing Sekiro’s duels is Posture. Like the Dark Souls mechanics of Stamina and Poise it appears to be descended from, Posture acts as an intangible, background concern that must be dutifully managed in order to maintain efficient offence. Where Stamina governed the number of attacks, blocks, and evasions that could be performed before needing to pause for recovery, and Poise defined the number of hits that could be blocked with a shield before being staggered – thus vetoing overly passive play – Posture pushes both concepts forward in tandem.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Sekiro seems to balance its fights on a seesaw of Posture dominance. The stat is increased by perfectly timed blocks and offensive parries and by landing hits (a slight nod to Bloodborne’s ‘regain health by counterattacking’ system there), and is lost by taking damage and blocking unnecessarily. High posture means a dominant position, low posture puts you closer to a gory deathblow, and is vital to inflict upon bigger enemies. In that respect, you can also see the system as a more involved evolution of Dark Souls’ massive back-stab and shield-parry hits, and Bloodborne’s post-stun Visceral Attacks.

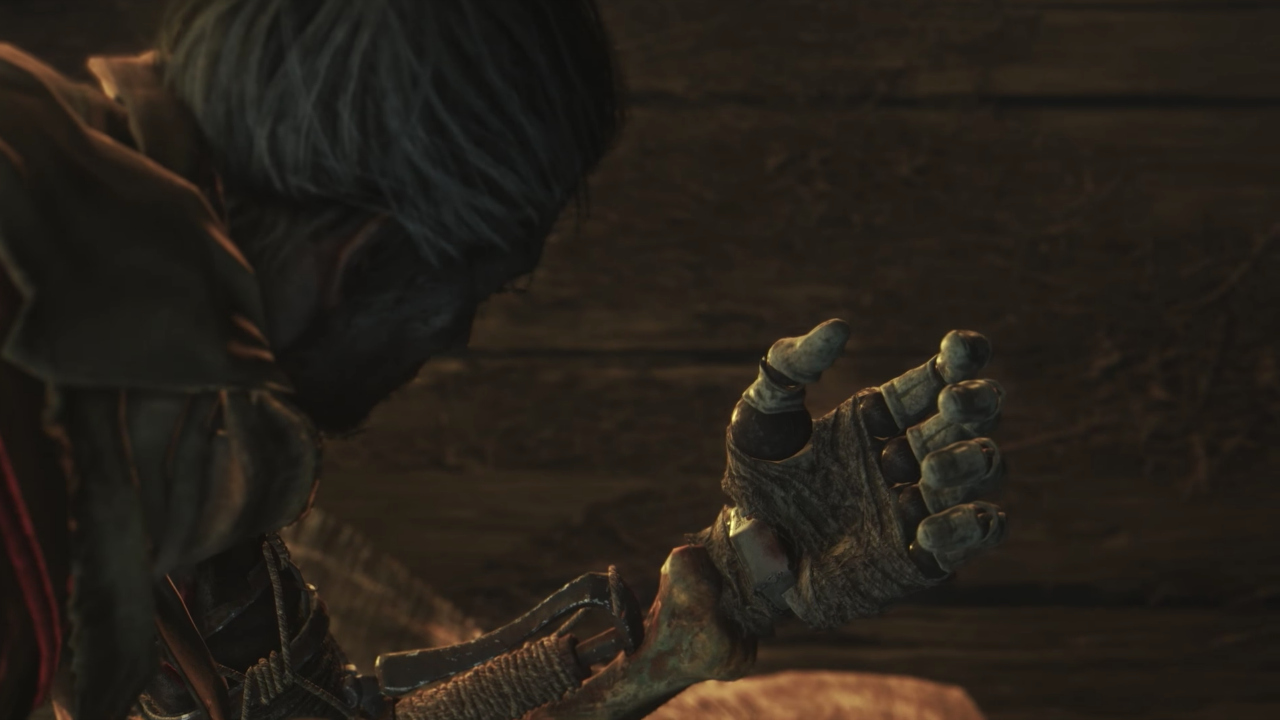

Beyond this, there are also different combat stances (confirmed, but yet to be revealed), multiple prosthetic gadget attachments for our protagonist’s left arm, and the ability to jump-evade and grapple our way around battles. With certain enemy strikes and actions also coming with special threat warnings, it sounds like Sekiro’s combat is being built with more than enough options and demands to recreate the spirit of methodical, sandbox depth that Soulsborne thrives on.

The world: How does historical Japan stack up against the intricate nightmares of Lordran and Yarnham?

Okay, onto the other glue that holds a Souls game together. It’s a hackneyed cliché to the point of white noise to describe the setting of anything as being ‘like a character itself’, so of course I won’t do that here. But few games have ever made their environments so fundamental to their storytelling and tone as Miyazaki’s previous works. Dense with almost subliminal clues and indicators, richly intertwined with half-glimpsed, half-details littered throughout item descriptions and loading screen annotations, Miyazaki’s game-worlds are lavishly details sources of atmosphere and meaning. And that’s before you even get near the intricately connected anatomy of their looping, moebius-strip architecture.

Most of that seems to be making its way through to Sekiro. From is promising a more openly explorable world this time around, which possibly speaks to the game’s reduced RPG emphasis and a less pronounced difficulty-gating system. The addition of a vertical element, grappling hook, and stealth play should give us a whole new toolset with which to appreciate, interpret, and explore the world, both physically and in terms of its hidden meaning. Indeed, we already know that stealthily passing enemies will reveal illicit information by way of overheard conversations – a first for From – which has huge potential to deliver both navigational clues and lore in a expanded and more dynamic fashion than we’ve seen before.

Stealth (and that grappling hook): Can Bloodborne really go Batman?

Here’s where things might look to take a massive swerve away from the Soulsborne approach. Sekiro’s stealth kills, jumping, and grapple-based, vertical evasion appear, at least superficially, to be anathema to From’s philosophy of ‘Face this threat, learn its ways, and adapt to overcome it’. But really, I think we’re looking at another evolution rather than a departure.

Dark Souls has always had optional combat. Sometimes these non-compulsory battles have come about by way of hidden areas and secret or non-vital bosses – looking at you, Painted World of Ariamis – while at other times, observation and exploitation of tough enemy patrol routes has been advantageous in initiating a duel at the right time, or even dodging the fight altogether in order to come back later, stronger and better equipped. At the very least, the act of getting an enemy’s attention and then ‘kiting’ them away from the pack, for a safer encounter on more favourable terrain, has long been a smart move within Dark Souls’ wider meta-strategy. If anything, Bloodborne expanded on this in places, through its use of wider, rangier environments and the increased intricacy of its pathways and roaming enemy placements. And let’s not forget that gun turret section in Old Yarnham. Yikes.

Soulsborne games have always been as much about combat preparation as combat itself, with careful positioning and timing fundamental to the whole enterprise. These games are about taking full responsibility for your violent interactions, and the precise means and circumstances by which they play out. The influx of more formal stealth systems, and more options for observation and positioning through tactical verticality, actually feels like a natural extension of that philosophy, however radical the new gameplay additions might seem.

The RPG side of things: How much control do really we have over our character?

Okay, here’s the biggie. Sekiro does not have an explicit RPG element. There are no stats to modify, no complex armour sets to hunt down and level up, and there’s much less overt focus on builds and personalisation in general. This might send many Dark Souls players screaming for the wistfully rendered, cherry blossom-coated hills, but I’m not too worried. Let’s not forget that Bloodborne itself very much streamlined the numbers side of things in order to put a greater emphasis on immediate in-game action. Further finessing the focus onto active combat options rather than statistical background work doesn’t necessarily mean that Sekiro is going to be a shallower game.

While we play a set character in Sekiro – and as such, don’t have the same ludicrous scope for versatile RPG class-building seen in Dark Souls – the extra layers of world interaction and combat preparation look like they might well compensate for the removal of farmed upgrade materials and ultra-specific armour buffs. And that said, we still don’t even know how the various gadget attachments for our hero’s arm will work. With their functionality seen so far ranging from a giant umbrella shield, to a firecracker distraction, to a heavy demolition axe, there’s clearly a lot of versatility to play with here, even without hundreds of pieces of kit to hunt down.

With the depth of basic sword combat already offering a huge amount of nuance to keep track of, it feels like, with all of Sekiro’s gameplay elements combined, there might well be more than enough personalised depth of approach here to maintain that distinct sense of experience ownership that makes From’s previous games so vital. The specific execution certainly swings in a fresh, new direction, but the essence feels familiar.

Multiplayer: How much will other players help and hinder us?

Apparently they won’t. There is no multiplayer element of Sekiro. No invasions, no co-op takedowns of bosses, no online notes passed through the space between players’ worlds, like so many cosmic, classroom jibes. Clearly that is a major departure, no two ways about it. The ever-present air of unseen assistance and attack, of unknowable and unpredictable player presence, creates a very specific tension throughout Dark Souls and Bloodborne. Sekiro will not have it. This time it will be you, on your own, versus the game-world.

How you feel about that will likely depend on your tolerance for invasions and your reliance on helpers to smash through tough bosses. Given Sekiro’s penchant for precise, sword-combat purity, the lack of PvP perhaps feels like a missed opportunity, but I can’t help feeling a certain – perhaps elitist – satisfaction, knowing that every player will now get the full benefit of From’s immaculate boss design without the option to call in a friend and bluntly streamroll through those standout battles.

Death: How does it work?

We don’t yet know exactly, but we do know that, in the spirit of its ancestors, Sekiro will keep death interesting. We’re almost definitely not looking at a reproduction of the exact same systems, mind, whereby currently held currency is dropped at the point of death, and can be recovered with careful play. Sekiro’s removal of the RPG elements that make those Souls and Blood Echoes so important will likely see to that. That possibly means that there will be no direct replacement for the bonfire/lamp-based checkpoint system either, though I’m absolutely speculating here.

But we do know that, in Sekiro as in Soulsborne, death is not really the end, but rather an opportunity for new action. Under certain circumstances, it is possible to self-resurrect upon death, and it’s also possible to delay that surprise-Lazarus in order to gain a tactical advantage. Leap straight back up, and you’ll launch right back into the fight that downed you. But wait a little while, and your killers will return to their previous business, allowing you to reappraise and restrategise how you wish to tackle them on the return attempt.

Certainly not the same as the traditional Souls method then, but there is a definite philosophical through-line. We know that resurrection in Sekiro will come with ‘consequences’, implying some sort of heavy cost for thumbing one’s nose at the Reaper. That means that, like with Souls’ hazardous runs to save lost loot, you’ll have to be very careful to make your second lives count. In much the same way that redeeming a Soulsborne death means committing to stepping up your game with increased care and caution, Sekiro looks to incentivise players who take the time to cool off after a death and regroup before responding. The hotheaded might be tempted to leap straight back into the fray for revenge, but the more patient might reap greater rewards. And if that’s not a new-school distillation of the Dark Souls mantra – ‘Keep calm, pay attention, don’t get greedy’ – then, well, it basically just is.