Keeping politics in games is more important than ever

2016 has been a uniquely terrible year for the world. The discourse of the United States election and Brexit has brought out the worst behaviors of both nations. Unarmed black men and women faced death at the hands of the people who are supposed to protect them; protestors exercising their constitutional rights came up against an increasingly militarized opposition. David Bowie and Prince died. Knack 2 was announced. It's been rough for a variety of increasingly awful reasons.

We don't delve into politics all that much on GamesRadar+, instead opting to dissect design, explore important moments in games, analyze trends, recommend lesser-known titles, and generally celebrate the positivity of how great games can be. Video games can be a powerful tool for escapism, to travel to far off lands, to become someone you're not, to feel in control of something in a world that feels like it's spiraling further and further away from us. These things are important; no one is saying otherwise.

But escapism isn't everything. There's only so far that you can disappear into a video game before you have to come crashing back out of it, into the real world, with all its problems and faults and issues. And to deny video games their ability to tell deeply moving stories that explore varying shades of the human condition is to deny them their very connection to humanity, to the very people who pour their souls into them. Video games can be toys, yes, in the same way that film can be mindless entertainment, but games can also be so much more.

There's a quote from Roger Ebert, noted film (and, to an extent, video game) critic that resonates with me a lot these days:

"We all are born with a certain package. We are who we are: where we were born, who we were born as, how we were raised. We're kind of stuck inside that person, and the purpose of civilization and growth is to be able to reach out and empathize a little bit with other people. And for me, the movies are like a machine that generates empathy. It lets you understand a little bit more about different hopes, aspirations, dreams and fears. It helps us to identify with the people who are sharing this journey with us."

If movies can provide a window into someone else's life, then video games have the ability to do it one better by actually putting us in their shoes. When we play games, we're not just watching characters act out their lines - we move them around, we decide what to interact with, and we decide how the story plays out. Watching Noctis hang out with his best friends is one thing; to actually play Final Fantasy 15, to decide when to set up camp, to decide what meal to eat, to decide what photos to keep and discard, these things bring us closer to the characters and the world. We're not just watching virtual friends interact; these are our virtual friends.

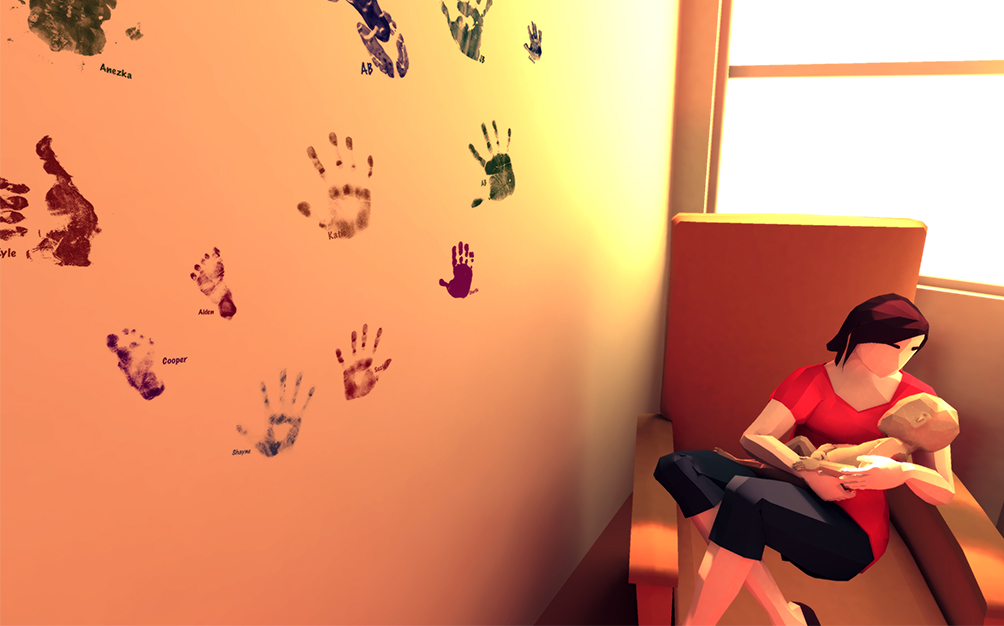

There seems to be a sea change underway, at least in small, initial strokes. Indie games, of course, have been leading the charge. That Dragon, Cancer is an interactive memoir of a family dealing with the gravity of losing a child to a horrific disease. 1979 Revolution: Black Friday is a Telltale-style adventure which explores characters living during the beginning of the Iranian Revolution. And so on. Independent developers telling personal tales and providing unique perspectives isn't new, but as the tools become more ubiquitous and easier to use, those stories will only continue to grow and improve.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Big-budget gaming is a different story - focus testing, market research, and ballooning development costs requiring a return on investment all but guarantee that these games need to appeal to as many people as possible without offending anyone. It's why Deus Ex: Mankind Divided brushes up against many of the issues affecting people in 2016 without actually saying anything about them. There's a lot of talk about 'mechanical apartheid' and oppression and 'augs lives matter' but none of that means anything when your protagonist moves through it all without feeling their effects, or when you realize the story is really about the Illuminati and it ends on a half-assed cliffhanger with no resolution of even rudimentary plotlines. Because it holds no real opinion, there are no stakes, and as such, its message is meaningless.

I was worried that this was it; this was the future of big-budget games, just a lot of talk with no real message or conviction. Then I played Mafia 3. Even with its mechanical issues - of which there are many - Mafia 3 is a game with purpose. As Lincoln Clay, an African American living in a video game version of 1960s New Orleans, you have to navigate a morass of racial slurs and epithets, bodily threats, and a minefield of general awfulness on your path to revenge.

This isn't just conveyed in the story; the racial politics of 1960s Southern America is embedded in its very design. Cops will respond differently in poor, black neighborhoods than they do in more affluent, white neighborhoods - you can hear the disinterest dripping from the police dispatcher's voice when you commit crimes in Mafia 3's opening sections. The part that got me the most was when I walked into bar where I was clearly not welcome. Confederate flags hung on the walls both inside and out, and the second I stepped inside, it was like hearing a record scratch. All eyes were suddenly on me, the bartender drawls out a "Can I help you?", the words 'TRESPASSING' appear in big bold letters on the top of the screen and now I feel like the smallest person in the world. I couldn't get out of there fast enough.

As a white man, I've never had to experience intolerance on this kind of level. But acting this out in a video game is one of the most deeply unnerving things I've ever played, and I know that the emotions I felt in that moment are a mere fraction of the fear and anxiety many African Americans face on a daily basis. This is what Ebert meant when he spoke about that 'machine to generate empathy', and Mafia 3 can be a perpetual empathy machine for a significant portion of the audience who plays it.

Even recent games like Dishonored 2 and Watch Dogs 2 take approaches at driving empathy, to varying degrees of success. In Watch Dogs 2, you're a young African American programmer living in San Francisco trying to take down Big Tech while finding yourself embroiled in numerous schemes, including bilking a Martin Shkreli-esque pharma exec for millions and uncovering a huge electronic voting fraud scheme. Dishonored 2 puts you in the shoes of a young woman whose throne is usurped by a group of despicable separatists, and must wade through villainy of all kinds to take it back. As she's doing so, she's witnessing the destruction her ineffectual rule has caused on the most vulnerable members of her kingdom. If you're not seeing the parallels to the real world here, you're not looking hard enough. Or at all.

That's not to say games haven't delved into real world conflicts before. I remember finishing Metal Gear Solid years ago, and after the robots and cyborg ninjas and clone nonsense, it closes with a few somber title cards describing how many nuclear weapons are still around, even after the end of the Cold War. Suddenly its hours of ridiculously over-the-top tactical espionage action and government conspiracy theories come crashing into reality. There's a difference, though, between using the politics of our reality as a backdrop and actually using those politics to say something meaningful about them in a way that still entertains as much as it enlightens. This is the challenge creators face as we enter the 21st century.

But even if certain games don't explicitly set out to be more than escapist media, that doesn't mean there isn't meaning to find within them. Sure, you probably won't find some deep connection in Geometry Wars besides feeling good about making your score get really high, but there's subtext to find in even something as outwardly simple as Dead Space, where humanity's relentless thirst for resources causes us to devise technology to destroy entire chunks of planets - effectively fracking taken to its most extreme conclusion - eventually unearthing the necromorph terror our hero fights through the trilogy. These parallels exist because media isn't created in a vacuum, and their creators bring with them opinions, viewpoints, and lived experiences which consciously or subconsciously find their way into the games they make. And not to sound like your old high-school English teacher, but this subtext exists whether you look for it or not. Seeking out that subtext, though, will connect you even closer, not only with the media you enjoy, but with humanity as a whole.

Many games don't always succeed as well as they could, whether the story ends up taking a nose dive in the third act, or their worlds are filled with too much busy work for their intention to shine through the bloat, but the fact remains that big-budget gaming is at least trying. It's realizing the power it has to craft relatable stories combining politics and escapism, and realizing the responsibility of providing an empathetic platform somewhere amidst all the virtual explosions. Big-budget gaming is starting to find that it can have a voice, it can have convictions, and it can do so while still delivering an entertaining product to millions of people. Change will come in fits and starts, but the fact that it's happening at all is a good sign for the future health of games as an art form. Not all games will do this, but some games will. Hopefully many will. These games are special; cling to them.

We live in increasingly uncertain times. It's ok to disengage and disappear into games for a while - our own mental health demands it. But we're all in this together, and rather than seeing games as a way to switch off from the world around you, look at the games you play and examine them for ways to connect with experiences that aren't your own. Seek out games with different perspectives. Read between the lines. Video games can be the greatest 'machine for generating empathy' ever devised - we just have to decide to turn it on and engage with it.