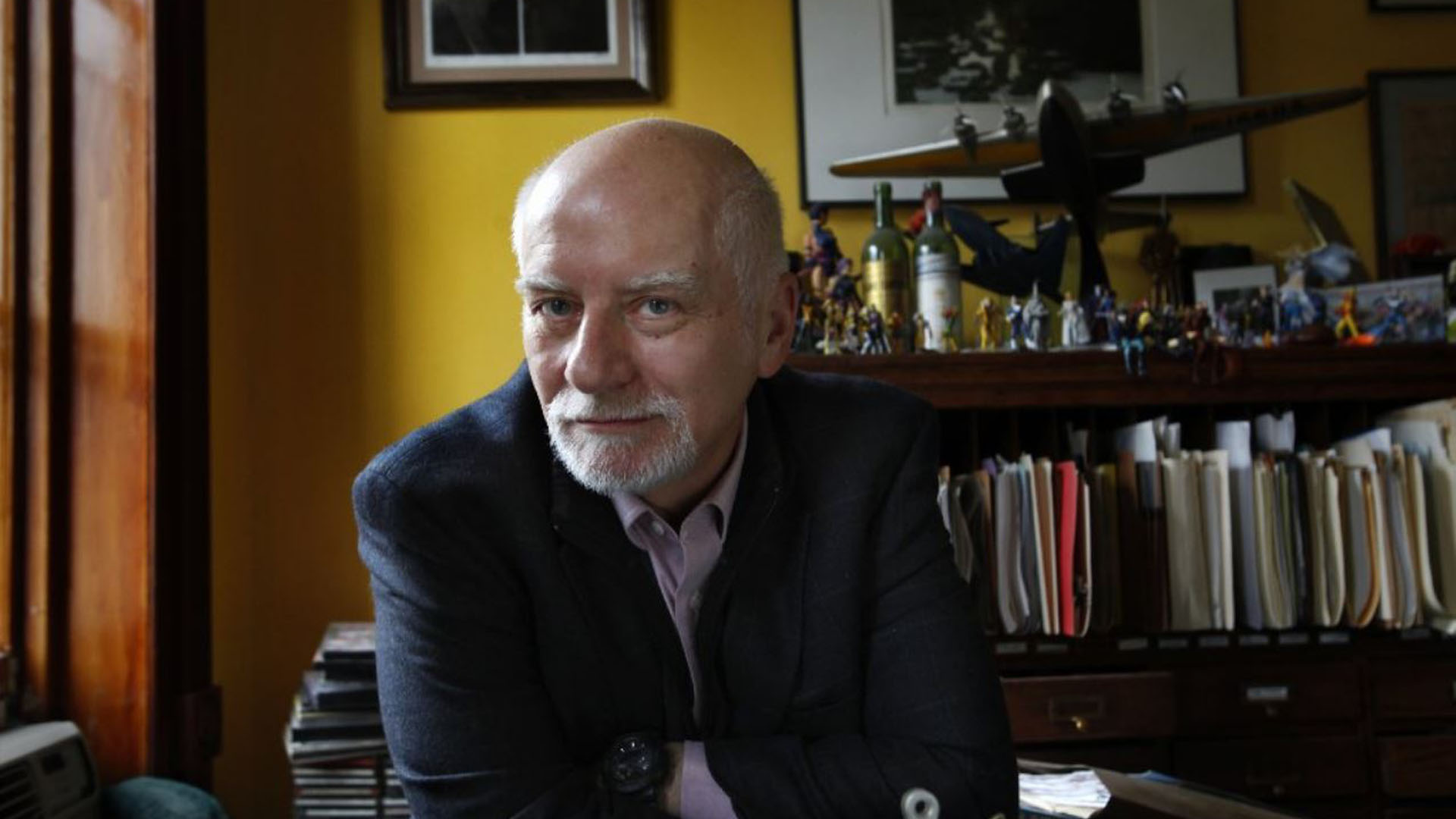

Chris Claremont on why X-Men is "heartbreakingly more relevant than ever"

Chris Claremont ways in on X-Men's past, present, and future

Writer Chris Claremont made his name with the X-Men – and the venerable mutant team was, in turn, defined by Claremont's vision over the course of his initial 16-year run and his subsequent work on X-Men in the decades since.

With the X-Men comics arguably back to heights it hasn't seen this the glory days of Claremont's original run while Marvel Cinematic Universe is developing their introduction to the MCU, this writer is uniquely poised to offer his knowledge of X-Men lore and his take on their place in the Marvel Universe.

Newsarama caught up with Claremont to get the venerable X-Men architect's insight into what this new era could mean for mutantkind.

Newsarama: Chris, the X-Men are riding high on the success of the X-Men comic line relaunched led by Jonathan Hickman, and anxiously talking about what Marvel Studios could do with the movie/tv rights cine they're back in the fold.

As one of the architects of their first huge wave of popularity, what do you think are the keys to making the X-Men the biggest franchise in superhero media again?

Chris Claremont: Probably the fact that a lot of the people that read X-Men in their younger days, 40-odd years ago when I was writing it, are now in a position to make decisions about media.

Everything has its evolution, and in our case, the people who grew up reading the book and loving the story and characters have now become the people making the decisions.

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

Newsarama: You mentioned the way so many of today's creators grew up with the X-Men, and how that's informed their modern trajectory. With the X-Men now on their way to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, what ground do you see that hasn't been covered with the team on the big screen yet?

Chris Claremont: I think the whole point is, all the characters and the stories that Dave Cockrum and John Byrne and Paul Smith and I told, the surface and structure have barely been touched.

The thing to bear in mind is, the whole current era of superhero films started with 2000's X-Men, and that caught 20th Century Fox totally by surprise. They weren't expecting a nine-figure opening weekend, that was unheard of for comic book movies. I would wager that set the stage for Spider-Man, and then Iron Man a couple years after that, and we all know what Iron Man led to.

If there's any group of characters that are ripe for more exploration, X-Men is it.

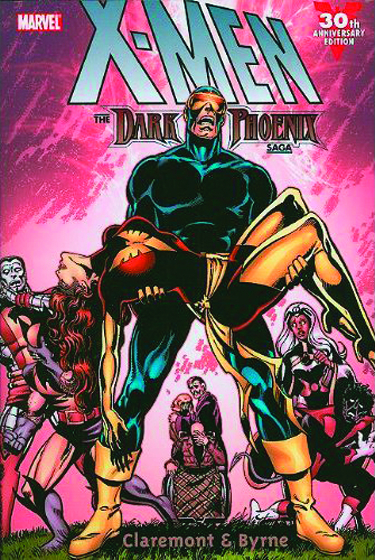

Newsarama: As you said, X-Men movies have only scratched the surface of the stories told in X-Men comic books – especially your own defining run. What story or stories do you want to see in a movie?

Chris Claremont: 'Dark Phoenix.'

Newsarama: And of course there have been attempts at adapting that story.

Chris Claremont: I'll explain. The challenge with X-Men is, if you notice how Marvel produced the Avengers films, they set them in motion with solo films – Iron Man, Thor, Captain America – then you had them come together for Avengers. So the audience gradually fell in love with the characters and the world those characters inhabit over a series of stories.

Hawkeye showed up in Thor. We barely saw him in the background, but he was there. Black Widow had a role in Iron Man 2. Kevin Feige was building and expanding the world piece by piece every step of the way. And with X-Men, that needs to happen as well – except it's one single concept.

You can't really do a solo Cyclops movie, then a Storm movie, then a Nightcrawler movie and so forth. You have to find a way to bring Xavier's school and the X-Men to the screen in a unified concept while also building the world piece-by-piece so the audience falls in love with it the same way.

For me as a storyteller, the ideal way to do that would be following HBO's lead with Game of Thrones, where you take 12 episodes – in other words, 12 issues – and you create the world and introduce the characters, and let the audience fall in love with them as you go along.

My problem with both iterations of Dark Phoenix onscreen, the original by Brett Ratner and the newer version by Simon Kinberg, is, I don't think you can do it effectively in 90 minutes. You can tell a good story in that timeframe, which I think Simon did, but it's not the evocation of the story that Dave and John and Paul and I created, it doesn't have the impact of knowing the characters and their dynamics and building to it conclusively in this narrative way.

The challenge is, in terms of a canon like X-Men, it's more like Harry Potter and Hogwarts, or Game of Thrones. It needs time and space to evolve and to bring the reader or viewer in and give them a result that's worth the investment of that time.

Newsarama: Do you think that kind of story would be better told in a series of films, or as a TV show, maybe something streaming on Disney+?

Chris Claremont: The paradigm I've seen now for telling that kind of story is, you can do it as a TV series and do that kind of evolving narrative justice, like HBO did with adapting Game of Thrones. You do it in those sequential bursts, 8 or 12 issues or episodes.

Newsarama: Right now, what do you see as the fundamental parts of the X-Men mythos that define the team for the modern age?

Chris Claremont: Heartbreakingly, as a concept it feels more necessary and relevant in the zeitgeist than ever.

Not long ago I wrote a story focused on Magneto in which the United States, under the mutant control act, is gathering up mutant families and imprisoning them in New Mexico 'for their own safety.' Kids are put in one facility, parents are put in another, and they'll be held until such time as its determined whether they're a threat to the country, and if they are, they'll be dealt with in accordance with federal policy.

And Magneto is talking about his own experiences as a younger man, gathered around people in a coffee shop who are all learning the news about the mutant control act – some saying 'It's about time, we've got to do something about these mutants." Magneto goes out to the facility, he's recognized as a mutant, they engage, and Magneto of course defeats them and dismantles the facility.

But the point is, if one group can be dealt with in this way by government fiat, what's to stop them from going after any other group?

The thing with mutants is, they've always stood in for the disenfranchised and downtrodden. And no matter how hard they fight, how hard they work to live among humans, the humans always push back with new laws and new ways of hurting mutants.

What I'm saying is, when we take steps forward, they're not irreversible, unfortunately. So how do we address the people that are hurt by that? How do we address our fellow citizens who are caught in the middle?

I don't think there's an easy answer, but it's a question that I think needs to be raised. And for good or ill depending on the circumstances, X-Men is the place in comic books that question always seems to be asked.

Make sure you've read all the best X-Men comics of all time - Claremont is the writer behind many of them.

[Editor's note: This interview was originally published November 7, 2019.]

I've been Newsarama's resident Marvel Comics expert and general comic book historian since 2011. I've also been the on-site reporter at most major comic conventions such as Comic-Con International: San Diego, New York Comic Con, and C2E2. Outside of comic journalism, I am the artist of many weird pictures, and the guitarist of many heavy riffs. (They/Them)