Alan Wake turns 10: Remedy's game took five years to emerge from the darkness of development, the studio explains how it finally saw the light

As Alan Wake celebrates its 10th anniversary, Edge Magazine tells its extraordinary development story

When Sam Lake was a kid, he spent his summer holidays on an apple farm in Raasepori in the south of Finland. One day, while exploring the rundown outbuildings, he stumbled across a treasure trove of junk. Among it was an old light switch. He called it his "clicker".

"To me, stuff like that always felt particularly mysterious and magical," he tells us. "I love old rusted machine parts that you can't quite figure out, old telephones and radios." The switch became one of his favourite toys, a magical totem with secret powers.

It wasn't until the little boy grew up and became the lead writer at Finnish video game developer Remedy Entertainment that he realised what the clicker was really for. In Alan Wake – a game about a horror novelist's attempts to save his wife from a supernatural power – the clicker becomes a metaphor. Terrorised by an evil force using his own fiction against him, Wake is trapped between waking reality and nightmare.

Follow the light

"A light switch felt like the perfect symbol," Lake explains. "In Alan Wake's world, the monsters that your imagination conjures up in the dark come true, but they are still destroyed when the lights are turned on. Darkness equals madness and terror, nightmares and death; light equals sanity and safety." The clicker had revealed its true power.

"Follow the light" is the most basic instruction in Alan Wake. When Wake's wife disappears, the player goes on a terrifying journey to rescue her. Wandering through dark, empty forests, deserted saw mills and creepy diners, you encounter the Taken – possessed townsfolk who inhabit the shadows and can only be banished by light – flashlights, flares and the odd UV spotlight.

"Lighting is probably the most important technical aspect in Alan Wake," says Oskari Häkkinen, the former head of franchise development at Remedy. "Light is a weapon but it's also thematically important throughout the game.

We wanted the player to really feel different emotions depending on the amount of light that was present – safety, fear, insecurity, resolution – and to have the feeling of being either totally lost or having a sense of direction by following light. There are so many layers to it that there weren't any off-the-shelf solutions for the lighting. Building the tech allowed us to fulfil the creative vision."

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

For Remedy, journeying into the light wasn't simple. Development took five years, with more twists and turns than Wake's stumbling, midnight sprints through the woods. A PC version was started then scrapped, and an episodic XBLA release was mooted then abandoned. Had the team realised how long it would take to escape the darkness, they would have reached for the clicker themselves.

Shifting goals

What really delayed Alan Wake for so long? "The biggest mistake we made," Häkkinen says, "was following a sandbox design. It did not fit with our story-driven focus." Originally, the game was an open-world experience set across a huge map with mist-shrouded forests, an eerie lake, power plants and a Twin Peaks-style town that players could explore.

Like novelists, game designers need to create their worlds and populate them. Unlike novelists, though, game designers also need to create every tree, shrub and rock that world requires. With that in mind, Remedy sent a research team through Oregon and Washington State and across the border into Canada. They took photos of mountains and lakes, diners and motels, visited the Washington locations where horror movie The Ring was shot, and camped out in the Pacific Northwest's woods.

Even after they returned to Finland with 60,000 photos on their hard drive, they still sent the odd request to their publisher's Seattle offices asking Microsoft to fill in some gaps, according to Häkkinen. "We asked them to take reference photos of shrubs and trees, or to go out into the woods to record ambient sounds – at night!"

The research fed into the team's tech, including a proprietary world editor featuring a number of procedural tools that evolved out of Max Payne's MaxEd level editor. With only 55 on-site staff at the peak of production, a surprisingly small number for such a sprawling game, Remedy needed to generate environments quickly.

"In Alan Wake's world, the monsters that your imagination conjures up in the dark come true"

"An unconventional game requires unconventional tools," Häkkinen explains. "We spent lots of effort in the early stages of development creating biotypes that meshed together, based off the research photos we took. Now, if we place a road in the middle of the world, for instance, the system automatically knows not to put trees or grass on the road. It also automatically generates sprouts of grass coming through the edges of the tarmac and [ensures that] the grass type is in line with the vegetation surrounding the road. In addition to that, it'll add gravel and a ditch on the sides of the road. The effort put into making these systems work saved us time later as no post editing was needed, and they allowed our artists to work very efficiently."

As the team built its sandbox prototype, though, it was apparent that something was missing. The freedom to go anywhere robbed the story of its purpose. As any good horror novelist will tell you, the slow creep of dread requires careful pacing. When players can abandon the search for their wife and go off logging instead, it's hard to maintain the requisite atmosphere.

"A thriller is very much like a rollercoaster," Häkkinen says. "You need those build-ups to make the plunges feel all the more exhilarating. We just weren't getting this in a sandbox design because all the game-istic things you need were detracting from the story being the focal point."

Although ditching the sandbox was frustrating, the game benefited. The open-world engine gave this now-linear horror story an agoraphobic feel. Häkkinen: "Because the environments were naturally much larger, we could make reference to things that could be seen in the distance and so foreshadow events. We could create landmarks so the player always had a sense of direction."

It gave a sense of a unified geographical space rather than a collection of separate levels. "Having flexibility within the environments also gave us the opportunity to make any given path as wide or as narrow as we pleased," Häkkinen explains. "It allowed us to play around with gameplay – narrow stealth areas like when the cops are chasing Wake, and wider areas to allow exploration and that sense of: 'Oh shit, I'm lost... what's in the woods?' So, yeah, it resulted in a much better game and it removed the linear feeling on the whole." It also, on a different level, made perfect dramatic sense: a game about a writer should feel authored rather than emergent.

Tortured soul

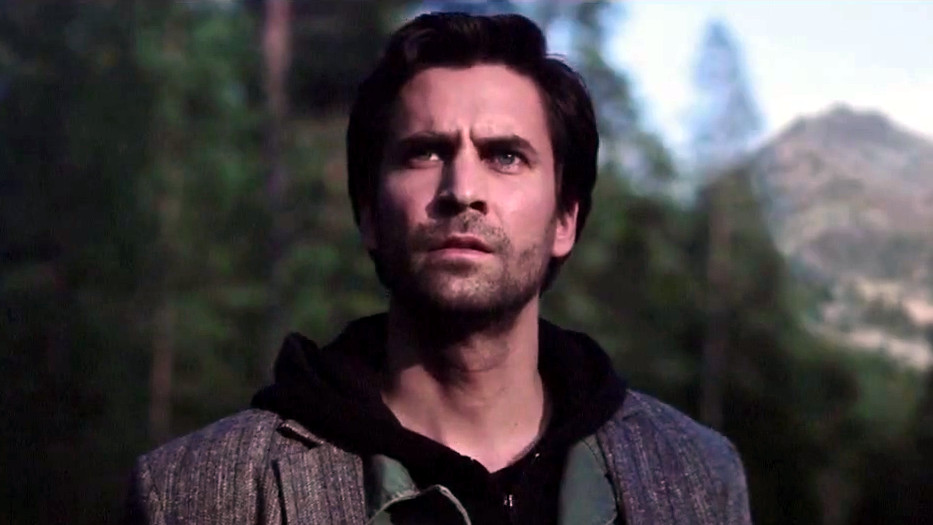

Not many games have an author as their protagonist, let alone a horror novelist suffering writer's block. Dishevelled and unshaven, Wake's an unlikely video game hero. "He's a bit of a rock star," Lake suggests. "He's troubled, he has this darkness inside him; he has a temper, he's not entirely in control. In the earliest drafts he was more of a victim, but along the way he grew stronger, more active; he got some attitude, and clear flaws. That makes a character interesting."

Ignoring the usual process of sketching concept art for the character, Remedy's design team instead hired actor Ilkka Villi to play Wake in a series of photoshoots and the inevitable motion-capture sessions. Yet the character's essential trait wasn't so much his look as his voice.

For Lake, who'd previously written the Max Payne games with their hardboiled monologues, Wake's profession made him unique. "I wanted to find a natural storyteller who could tell his own story, and that made me think about a writer. In a way you are playing the story Wake has written, the mysterious manuscript of a novel, Departure, where he himself is the main character."

With its episodic structure, cliffhangers and 'previously on' recaps, Alan Wake makes more than a few nods to TV shows from Lost to Twin Peaks. But it's also a supremely literary game. Stephen King is an obvious inspiration, although there are other influences including Mark Z Danielewski's House Of Leaves – a disorienting, interleaved novel about a strange house in Virginia that's told by a variety of different voices.

"It's one story, but it's many stories at the same time," says Lake, who counts House Of Leaves among his favourite novels. "While those different stories come in different forms and styles, the book still manages to feel like one whole. That's how I see a game. A game is a large entity, and you can fit many things inside it: manuscript pages, radio shows, TV shows, fictional bands and their music, and so on. And they all mirror each other and the main plot, and form one whole."

Microsoft originally planned to release Alan Wake as episodic content in two-hour gameplay increments over a series of ten weeks via XBLA, each one 'airing' at the same time each week. Back then, with Lost riding high in the TV ratings, it was a tempting proposition, but sadly the publisher's conservatism eventually trumped innovation. "We played around with various models of delivery," Häkkinen explains. "But, of course, these are business decisions which even Remedy, as the IP holder, doesn't control. I think we were already carrying a lot of risk with Wake exclusive on one platform only, plus it was also a new IP. It would have required balls of steel to take on the risks of introducing a new episodic business model too." Microsoft instead followed a traditional retail route, with 'The Signal' and 'The Writer' released as DLC. Nearly two years after its debut, Alan Wake was also released on PC.

What difference does it make to have a writer as the hero? Apart from the late sequence where we journey into Wake's imagination, nouns replacing objects onscreen with surreal menace, the game is less about the act of writing than simply surviving. Wake isn't a soldier or space marine; he wears hoodies and elbow-patched tweed jackets, not power armour. He's vulnerable, and that ups the horror stakes. Encounters with the Taken – inky shades that whisper menacing nonsense such as "You're going to miss your DEADline!" – frequently demand flight, not fight.

As you're sprinting blindly towards the next light, the camera often pulls back to reveal a Taken hot on your heels. No wonder Wake's most useful response is his duck'n'dodge move, a slow-mo animation that reinforces how much danger the hero's in. It gives the player an incredible sense of physical peril. Even when you master the core combat mechanics – an innovative combo of using light and projectile weapons – to kick some ass, you rarely feel as powerful as, say, the Master Chief.

The game's horror is more than just visceral chills, however. It's character-driven, too, with a cast of memorable Bright Falls residents emerging from the cutscenes and in-game narrative, from Rose, the over-eager diner waitress with a thing for writers, to the Anderson Brothers, former heavy-metal rockers suffering from dementia.

Then there's Barry, Wake's agent, who's never less than utterly OTT. "We had a saying at the office while working on the game," Lake explains. "'Adding Barry to any scene will make it better.'"

He's a fantastic piece of comic relief, a character who can flag up all the craziness that's happening within the game. "It gets awfully gloomy for the player to be stuck in Thrillerville for ten or more hours, and the same is true for the developers," Häkkinen suggests. "Barry is Wake's sidekick, his friend, his literary agent and a New Yorker who hates small towns. On top of that he's got allergies to dust, pollen and grass, so you already see how we created this fish out of water by putting him in Bright Falls. He's a character that you either hate or absolutely love." The Remedy team loved the character so much that they named one of their HQ's meeting rooms in his honour.

Reflecting on release

Alan Wake was released in May 2010, an Xbox 360 exclusive that billed itself as a psychological action thriller. Its release slot was scarier than anything Stephen King could come up with, hitting shelves on the same day as Red Dead Redemption in the US. Initial sales reports showed it selling just 145,000 copies in North America in its first two weeks – compared to RDR's May sales of 1.51 million – a fact described by one online news outlet as a "US sales nightmare".

Was it really that bad? "It certainly was a competitive [release] window," Häkkinen says. "We talk about 'bloodbaths' all the time when referring to a window, but there were about six titles that launched on the same day as Wake."

But Alan Wake eventually crept over the one million worldwide sales mark, a progression paced at much the same speed as its slow-burn narrative. "Word of mouth definitely carried Wake through, and it's nice to see people still talk about it as a must-play," Häkkinen notes. It's a game that, like its hero, has survived despite the odds.

Remedy isn't a company willing to run from its fears. After all, as Lake believes, legging it never solves anything. "Whether it's writer's block or some other crisis in your life, it doesn't really matter where you go or don't go, because that old log cabin is your head and the dark waters of the lake that surrounds it are the depths of your subconscious mind," he tells us. "The demons that surface from the lake will come knocking and the only way to banish them is to face them and shine a light on them." With Alan Wake's American Nightmare following in February 2012, Remedy demonstrated that it was willing to step back into the darkness again, ready to light it up.

This feature was first published in Edge Magazine #236. Subscribe to Edge Magazine for only $9 for three digital issues and show your support for long-form game journalism.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.