Why Resident Evil 7 highlights the limitations of VR horror

With or without PS VR, the opening of Resident Evil 7: Biohazard is a masterclass in slow-burn tension. The combination of careful pacing, atmospheric sound design and grisly environmental detail create a sense of place so potent that by the time you’re stepping over the threshold of the Bakers’ Louisiana home, you’re already on edge, instinctively tensing up in anticipation of the horrors to come. With the headset on, the feeling of trepidation as you push up against each door is especially strong. It’s the not knowing that thrills you.

If you haven’t played Resident Evil 7 yet and would like to go in completely cold, it’s time to tap out, because beyond this point lie a few minor spoilers. Suffice to say that your first encounter with another human being in the house sees that expertly cultivated tension start to melt away – assuming, that is, you’re playing in VR.

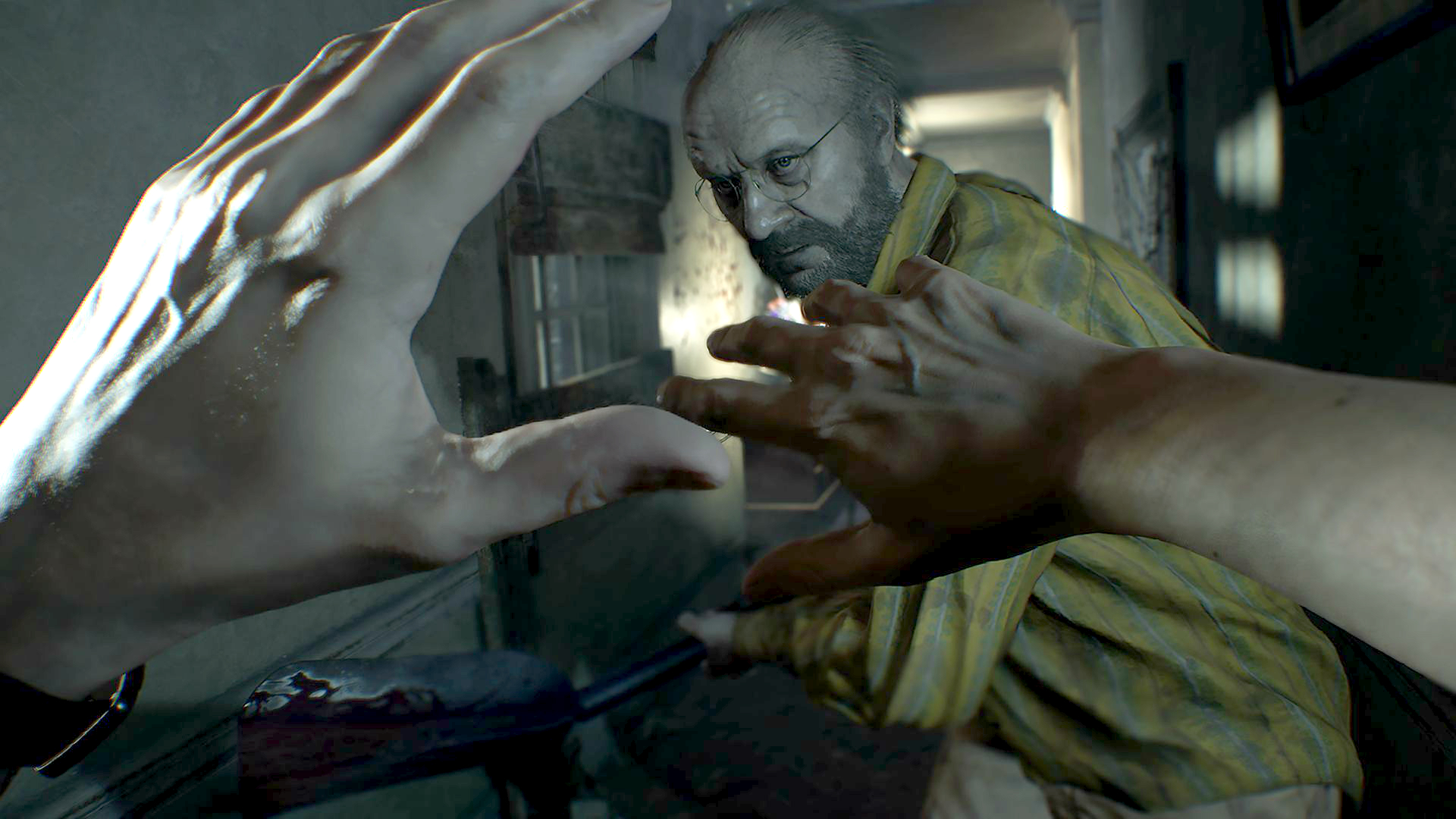

Already you’ll have noticed the flashes of black that replace certain transitional animations – when you’re exiting a car, for example, or picking yourself up from the floor. These are a necessary evil with current VR tech, designed to ease the potential wooziness or nausea that can accompany specific movements, and are thus forgivable. But when Ethan Winters adopts a defensive position, resulting in a pair of arms severed somewhere between the wrist and elbow hovering in mid-air, it’s a distraction too far. Being stabbed through the palm should be disturbing, but these bizarre, disembodied meat gloves lend a note of unintentional comedy to the close-quarters violence.

PS Move compatibility might have solved that issue to some degree. You could mimic Ethan’s actions by holding two motion controllers in front of your face to protect yourself, and keep them by your sides at other times to prevent floaty-hand syndrome from ruining the nervy exploration. Even so, it wouldn’t solve the one intractable problem of VR, which is the absence of physical connection. The moment someone (or something) tries to hit you is VR’s equivalent to the moment in a creature feature when the monster is fully revealed.

Whether it’s Mia swinging a chainsaw or Jack Baker with his giant shovel, as soon as your character is struck without any kind of tangible feedback in the real world, you automatically relax a little. On the TV, however, there’s a layer of abstraction that makes the illusion of violence and the threat of harm more persuasive – you feel trapped within the screen alongside the Bakers and the Molded. VR might convince you that you are there, treading those creaking, bloodied floorboards – but it can’t quite convince you they are.

For me, nothing in Resident Evil 7 came close to the profoundly unsettling final sequence in Arkham VR, where clever use of positional audio and a shifting, claustrophobic environment combined to make me afraid of turning around – and without the immersion-shattering awkwardness of using the right analogue to rotate my body in 30-degree increments. It’s a lesson that games purpose-built for PS VR will always work better than more traditional forms with bonus headset support, but more importantly, it’s a reminder that you can leave players squirming in discomfort without laying a finger on them. Perhaps Resi’s mutants simply aren’t as well-suited to VR as non-corporeal threats – the mere thought of Fatal Frame VR gives me the kind of shivers I wish I’d felt inside the Baker plantation.

This article originally appeared in Official PlayStation Magazine. For more great PlayStation coverage, you can subscribe here.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Chris is Edge's former deputy editor, having previously spent a decade as a freelance critic. With more than 15 years' experience in print and online journalism, he has contributed features, interviews, reviews and more to the likes of PC Gamer, GamesRadar and The Guardian. He is Total Film’s resident game critic, and has a keen interest in cinema. Three (relatively) recent favourites: Hyper Light Drifter, Tetris Effect, Return Of The Obra Dinn.