When Batman meets Batman - unpacking the meaning of "Legacy" in modern superhero comics

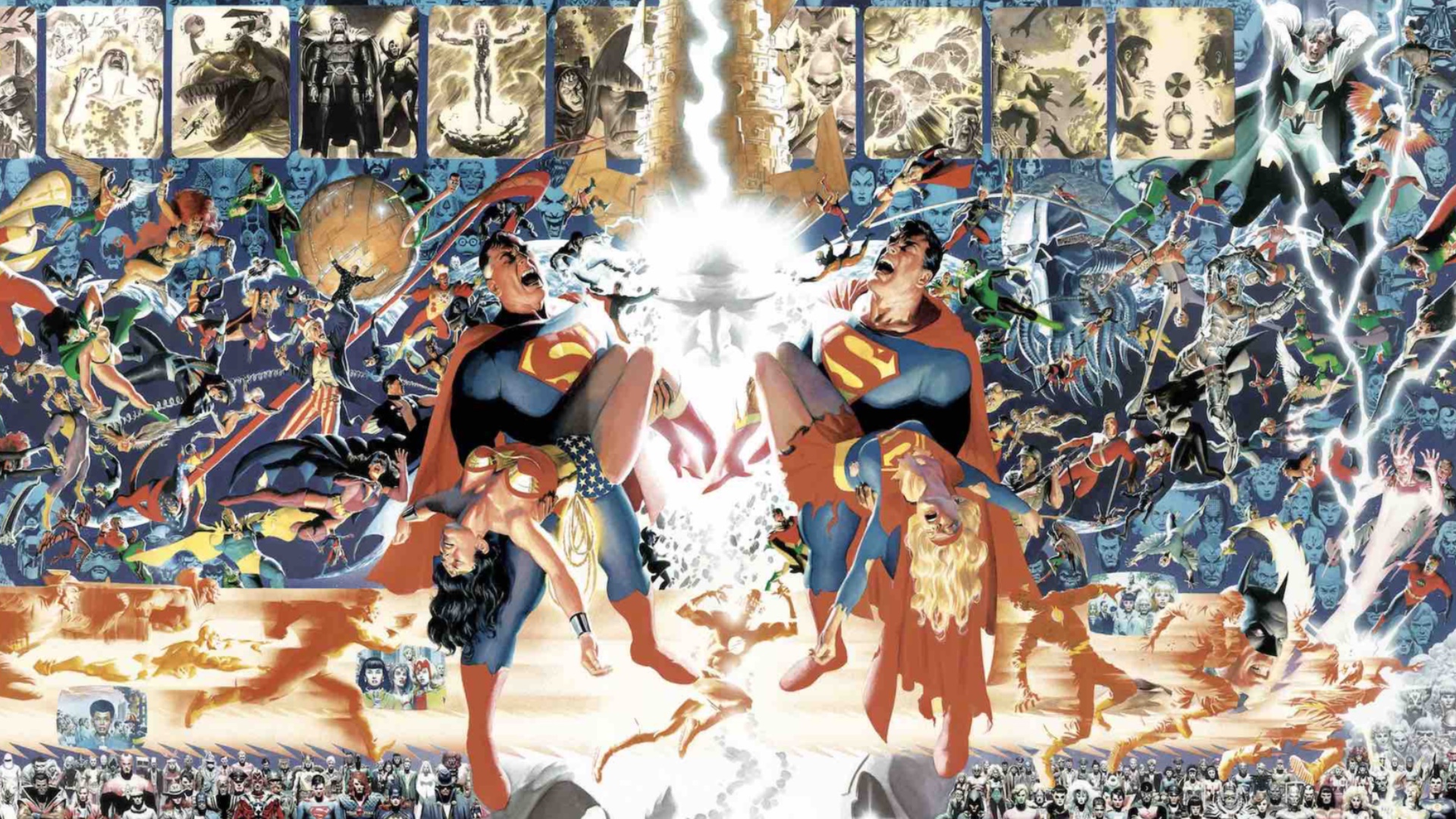

DC says Dark Crisis is "all about legacy," but what does that mean when multiple 'Variants' of heroes co-exist?

"It's about legacy."

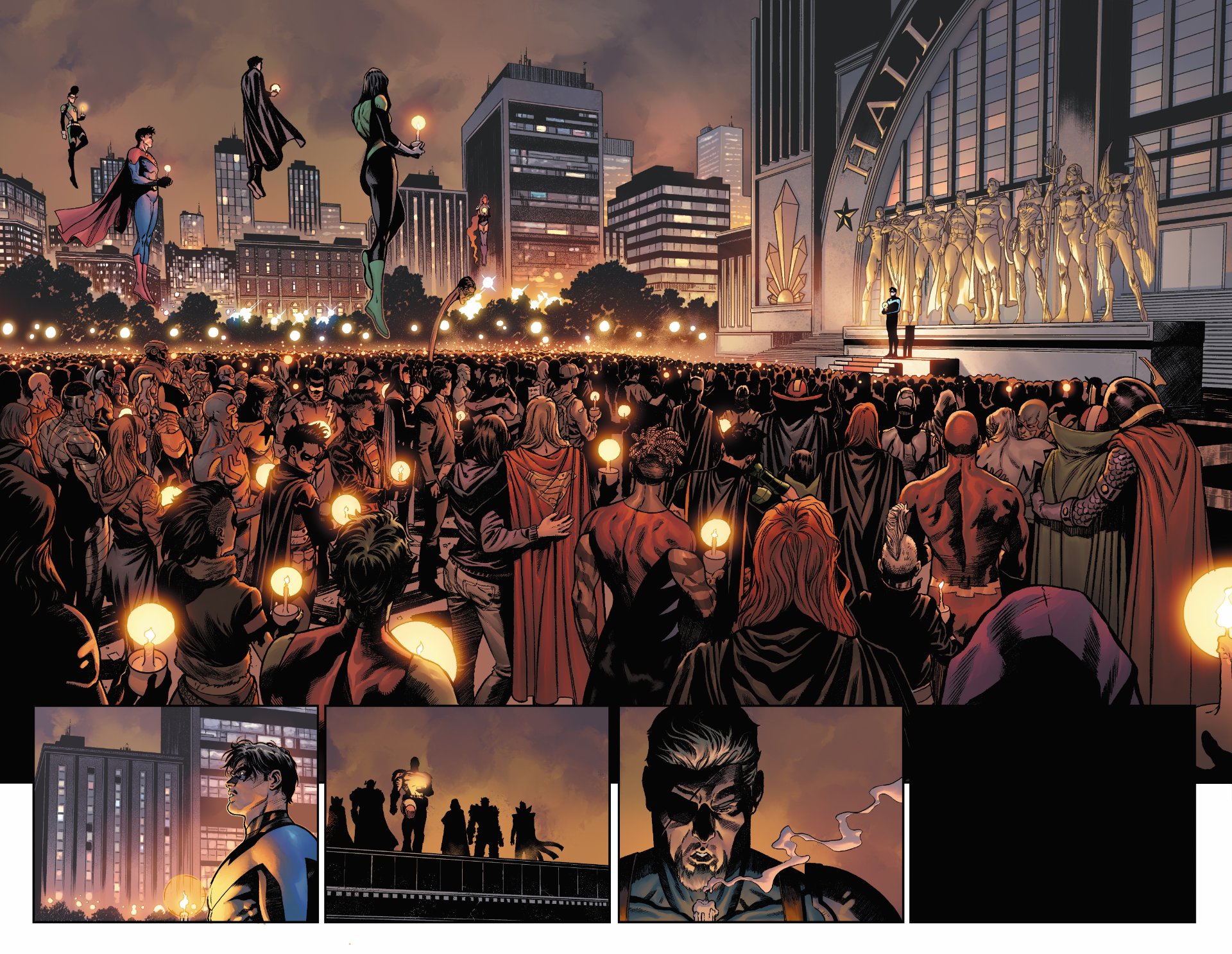

That's how DC's early tease for its now officially announced summer event Dark Crisis spelled out the story's premise, in which a so-called Dark Army will apparently slay the Justice League (though DC has also said they'll be "lost" and must be "saved"), leading into the event story itself.

And though the story's title, 'Dark Crisis,' certainly invokes the legacy of Crisis on Infinite Earths and its subsequent stories as well as 2017/18's Dark Nights: Metal and its 2020/21 sequel Dark Nights: Death Metal that play into the overall Crisis mythos, it's actually the legacy of DC itself and the publisher's core heroes that seem to be the driving factor in Dark Crisis.

Leading into Dark Crisis, 'Death of the Justice League' will seemingly kill off most of the core roster of the team with legacy heroes tied to those who will perish apparently stepping up to protect the DCU in their absence. Nothing new in terms of comics - the League has been replaced before, even en masse.

But killing the League as a whole and even shuttering the entire concept for an indeterminate period - all while simultaneously continuing the individual adventures of the League's members, and in some cases even the team's collective tales in a variety of stories spread across multiple realities and unmoored from the core DC meta-narrative - speaks to a modern idea of how superheroes and superhero continuity should be approached.

A legacy of legacies

Again, legacy heroes are nothing new - especially at DC. And over at Marvel, they're getting in on the action too, embracing 'variant' versions of popular heroes, telling flashback tales to some of their most popular eras, and packing their publishing line to the gills with multiple titles and stories featuring alternate iterations of many of their best-loved characters.

For fans of hardline continuity, keeping up with the many versions of different heroes and how they fit together can be frustrating.

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

But for those more casual fans looking to find new adventures featuring their favorite characters from movies and television, a somewhat bespoke approach to superheroes, where everyone can indulge their preferred version and find something that fits the way they see a given hero, can offer a much easier gateway into the mythos of superhero narratives that have been running, in some cases, as far back as the '30s.

In some ways, the idea that each writer who tells their tale of a given hero also puts their own spin on the hero's story, personality, and powers is a perfect and natural extension of the classical tradition of oral storytelling that dates back to the earliest days of humanity's fascination with gods and monsters - bringing the idea of superheroes who vary slightly from telling to telling even closer to the popular conception of superheroes as our so-called 'modern mythology'.

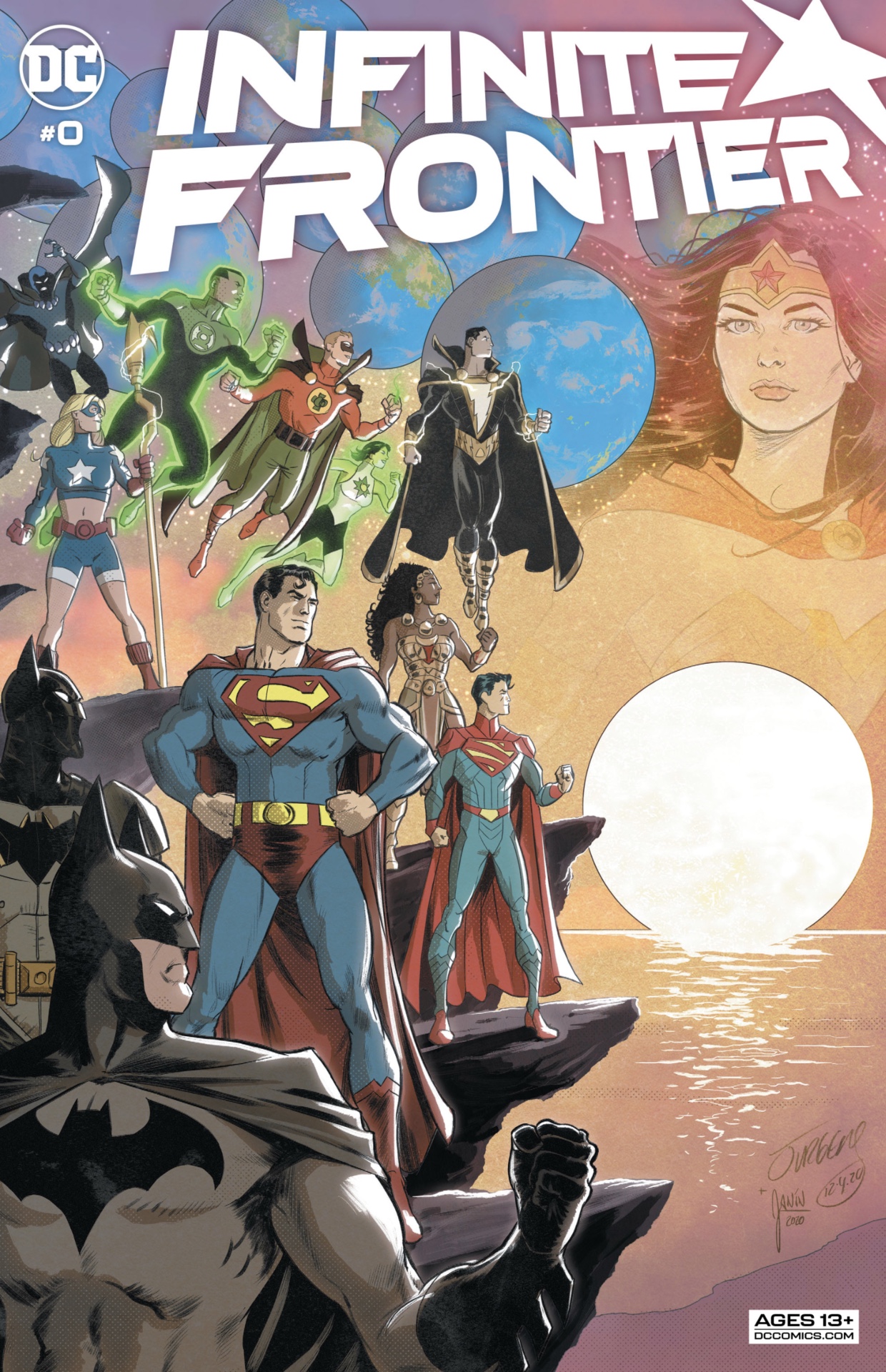

DC has gone so far as to make the idea of disconnecting heroes from their core narratives a literal, spelled-out part of their current 'Infinite Frontier' era, in which writers can pick and choose how they want to address past and even in some cases present tales of their characters, and every iteration and story relating to heroes like Batman, Wonder Woman, and Superman are considered 'real' parts of their story that exist somewhere in the DC Omniverse, to be tapped into at any given moment.

Dark Future

For example, even the timelines of the impending 'Death of the Justice League' and Dark Crisis are somewhat in question, as both stories' writer Josh Williamson has tweeted that the two stories take place somewhere in the nebulous "future of the DCU" - meaning DC is leaving plenty of room to keep publishing comics about Bruce Wayne, Diana, Clark Kent, and the rest of the core League members who will seemingly die in the interim, as mainstream DC continuity catches up to whenever "a bit in the future" actually arrives.

(By the way, we're also still waiting to see how or if previous future-set DC stories such as Future's End and Future State may catch up to the current DC timeline - with those 'Futures' edging further and further away).

For that matter, fans are already being conditioned to expect a return for the League in some fashion, with recent DC marketing pivoting to calling the team "lost" and must be "saved". That death-and-return cycle has been the norm as far back as 'The Death of Superman,' which, incidentally, was itself a massive driver of bringing fans from outside comics into the medium to buy copies of Superman #75 back in the early '90s.

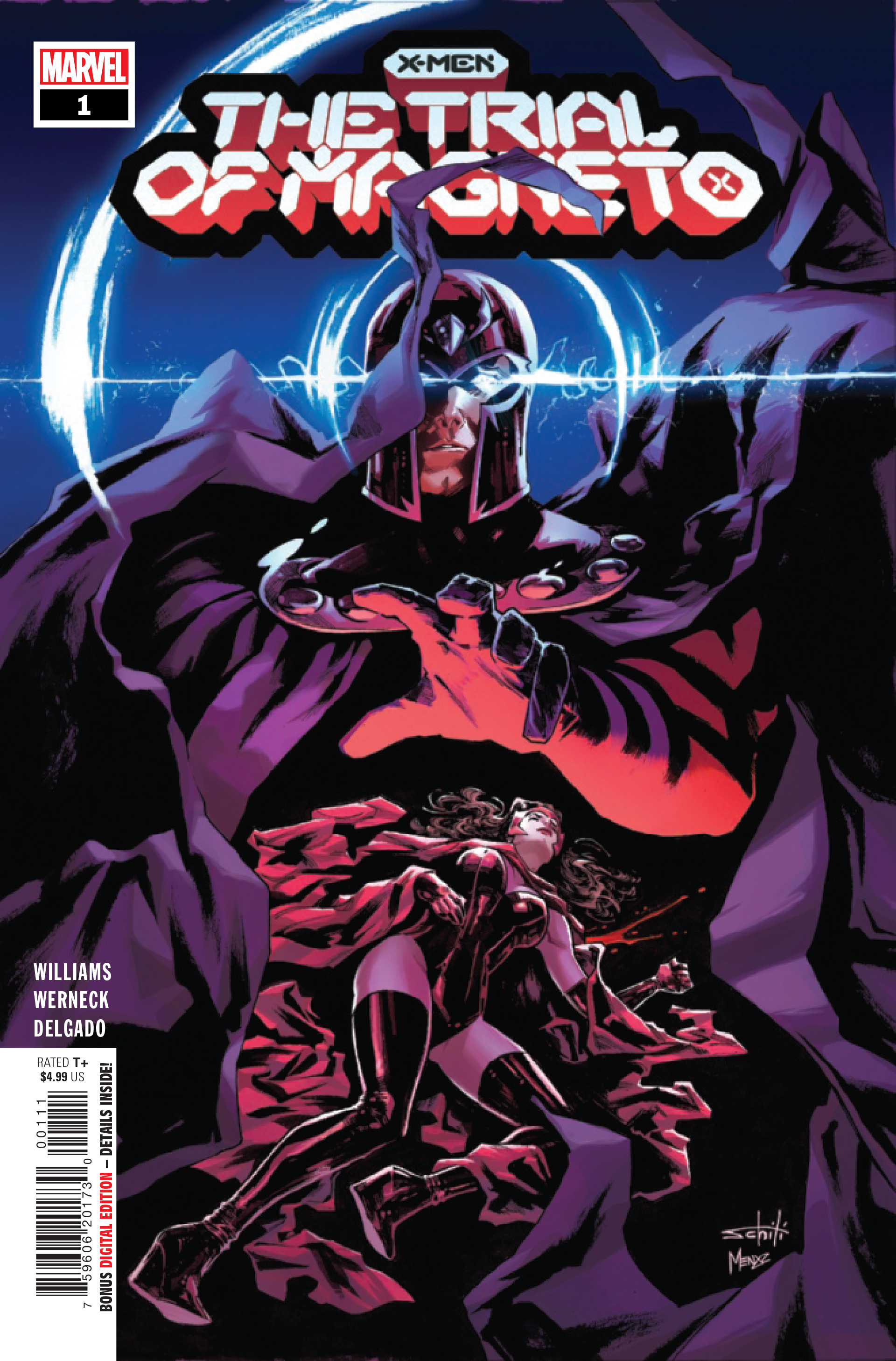

And at Marvel, things are no different, as exemplified by stories such as The Trial of Magneto and Darkhold, which, while both releasing simultaneously and both featuring Wanda Maximoff/Scarlet Witch as a core character, present Wanda in two wildly different status quos, necessitating readers put the pieces together themselves, or at the least accept that Darkhold is a kind of contemporary 'flashback' to a moment just before Trial of Magneto.

Marvel even has three versions of Spider-Man running around right now - Peter Parker, Miles Morales, and Ben Reilly. And the publisher just split Carol Danvers' Binary aspect into its own separate character - effectively making two versions of Carol, too.

Multiverse Multiplicity

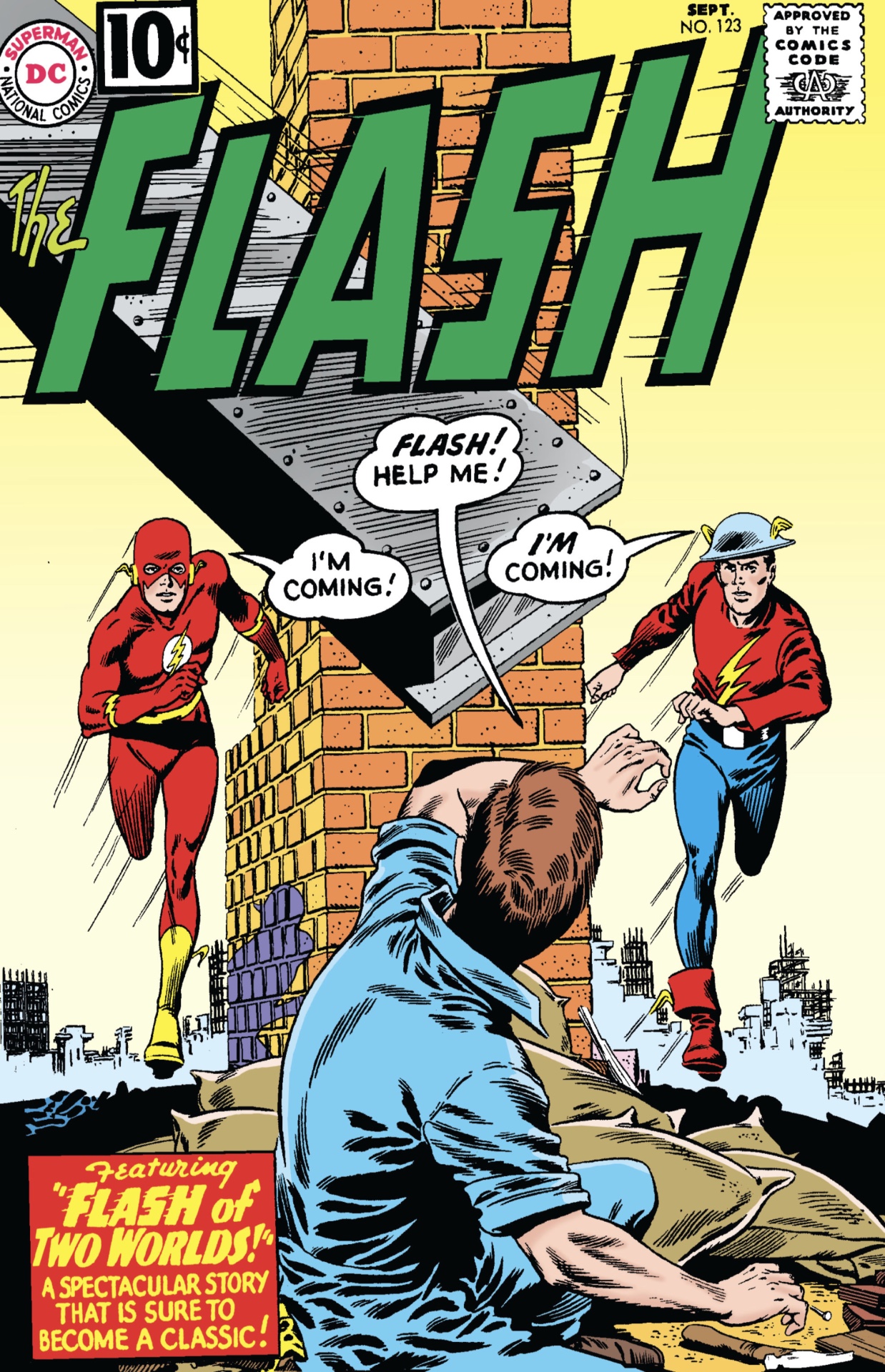

The idea of superheroes having multiple, concurrently active versions of themselves appearing in separate stories goes all the way back to the same roots as DC's multiverse (and therefore the concept of a superhero multiverse in general).

In Flash #123's story 'The Flash of Two Worlds,' Barry Allen teams up with Jay Garrick, his Golden Age predecessor, across dimensions in a story that established DC's Golden Age heroes as operating simultaneously with their updated, Silver Age counterparts on a separate Earth, aptly named Earth-2.

From there, DC's multiverse ballooned out with counterparts for nearly every DC hero on some alt-Earth somewhere, and an ongoing parallel narrative set on Earth-2 with multiple titles in its oeuvre - a kind of Ultimate Universe decades before Marvel set onto that idea.

But the multiverse came with a double-edged sword, at least in DC's perception, that the publisher's growing audience of readers would have a difficult time separating which adventures took place on which worlds, and which versions of the characters and their stories really 'counted' as a given hero's core history.

The result was 1984-85's original Crisis on Infinite Earths, in which the DC Multiverse collapsed into a single timeline with one narrative tying it all together, and stories set in alt-realities were retconned to accommodate the new status quo, with some aspects of the DC mythos - including entire characters and stories - intended to be jettisoned altogether.

It's worth noting that, around this time, the generation of readers that were kids in the '60s and who had been the first to grow up with the Marvel and DC universes as we know them were breaking into comic books and becoming driving forces in the industry - naturally skewing mainstream superhero comics more and more toward an idea of a shared, core continuity that would satisfy the long-held aspirations of what the narratives and characters the creators of the '80s grew up with could be.

Comics are for everyone

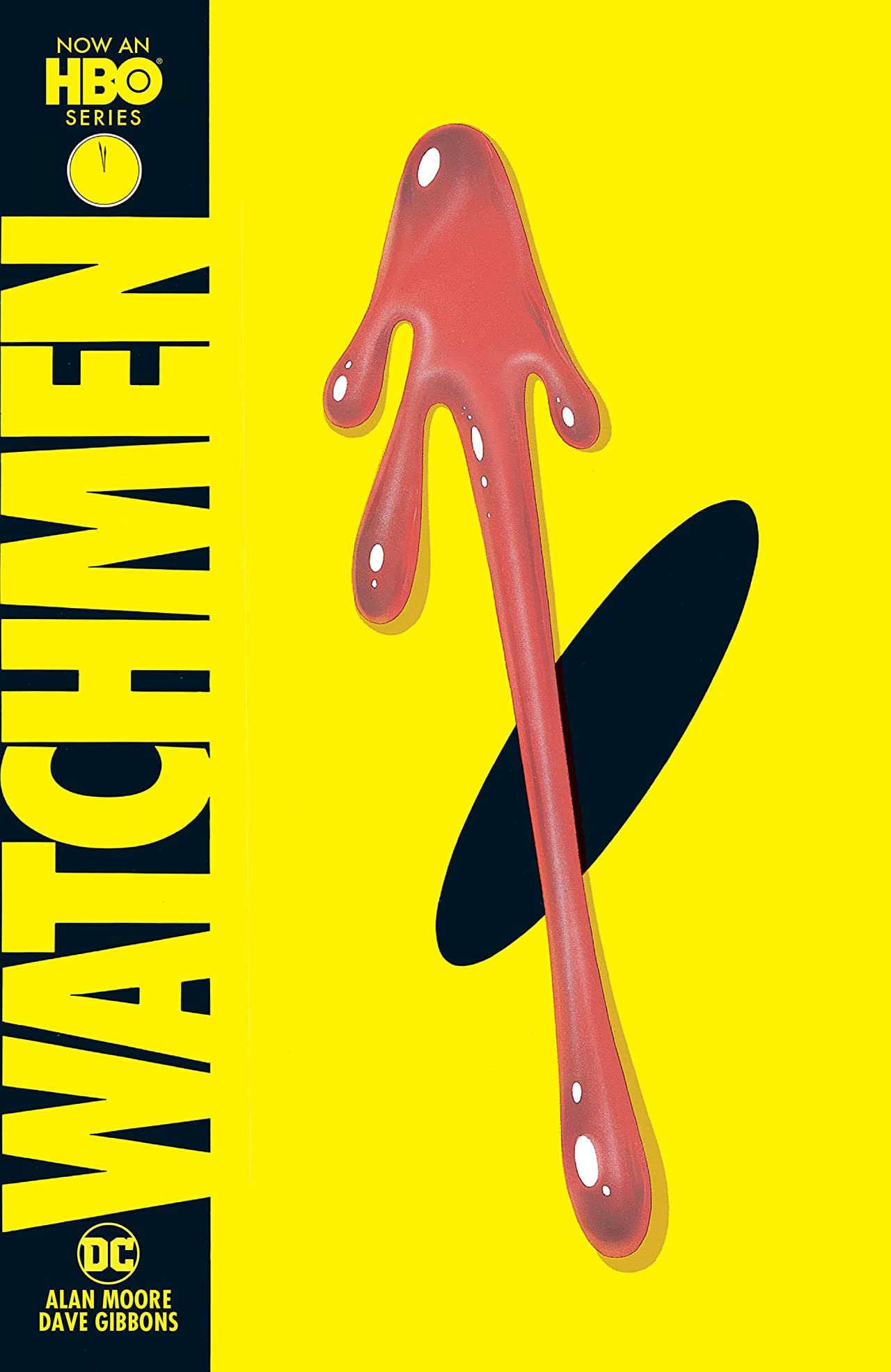

Curiously though, at the same time, as superhero comics were breaking into the mainstream more than ever, the stories that began driving consumership and readership of comic books increasingly became those stories that could stand apart from continuity as their own sort of individual works.

(This is also when the term 'graphic novel' started to become popular, not coincidentally).

Works such as Frank Miller and Lynn Varley's Dark Knight Returns and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen (both of which starred casts of heroes that, in modern terms, would likely be considered 'variants') caught the eye and wallet of readers outside the core comic book audience.

And along with Marvel's high-profile launches of new volumes of Spider-Man and X-Men with new #1 issues which invited brand new readers to hop right on board, the idea of superheroes as mainstream entertainment began to spread - thanks in large part to stories and titles that catered specifically to folks who hadn't already been reading about Batman and Spider-Man their entire lives.

Maybe even more curious, DC almost immediately began backtracking on its post-Crisis 'all-in' philosophy of a single unifying timeline, first by letting many of its stories contradict each others' new story status quos with individualized explanations and solutions for the changes to their subjects' continuity, and then by full-on publishing stories set specifically in alternate universes or timelines, such as the aforementioned Dark Knight Returns.

This also led straight into the launch of DC's Elseworlds with Gotham By Gaslight (RIP Brian Augustyn) and even the separation of Vertigo titles such as Hellblazer, Swamp Thing, and Sandman from mainstream DC continuity - with many of those titles again becoming among the most popular and enduring in DC's entire history, thanks in large part to their accessibility.

Variant-Verse

Nowadays, a more common practice is to increasingly embrace and incorporate all the different versions and aspects of characters into one massive storytelling soup that creators can ladle out as they please, with stories such as Marvel's Spider-Verse and modern Secret Wars, and DC's Dark Nights: Death Metal scooping straight from the bottom of the pot for a goulash of characters from across different worlds of their respective multiverses, with multiple versions of the same character teaming up together.

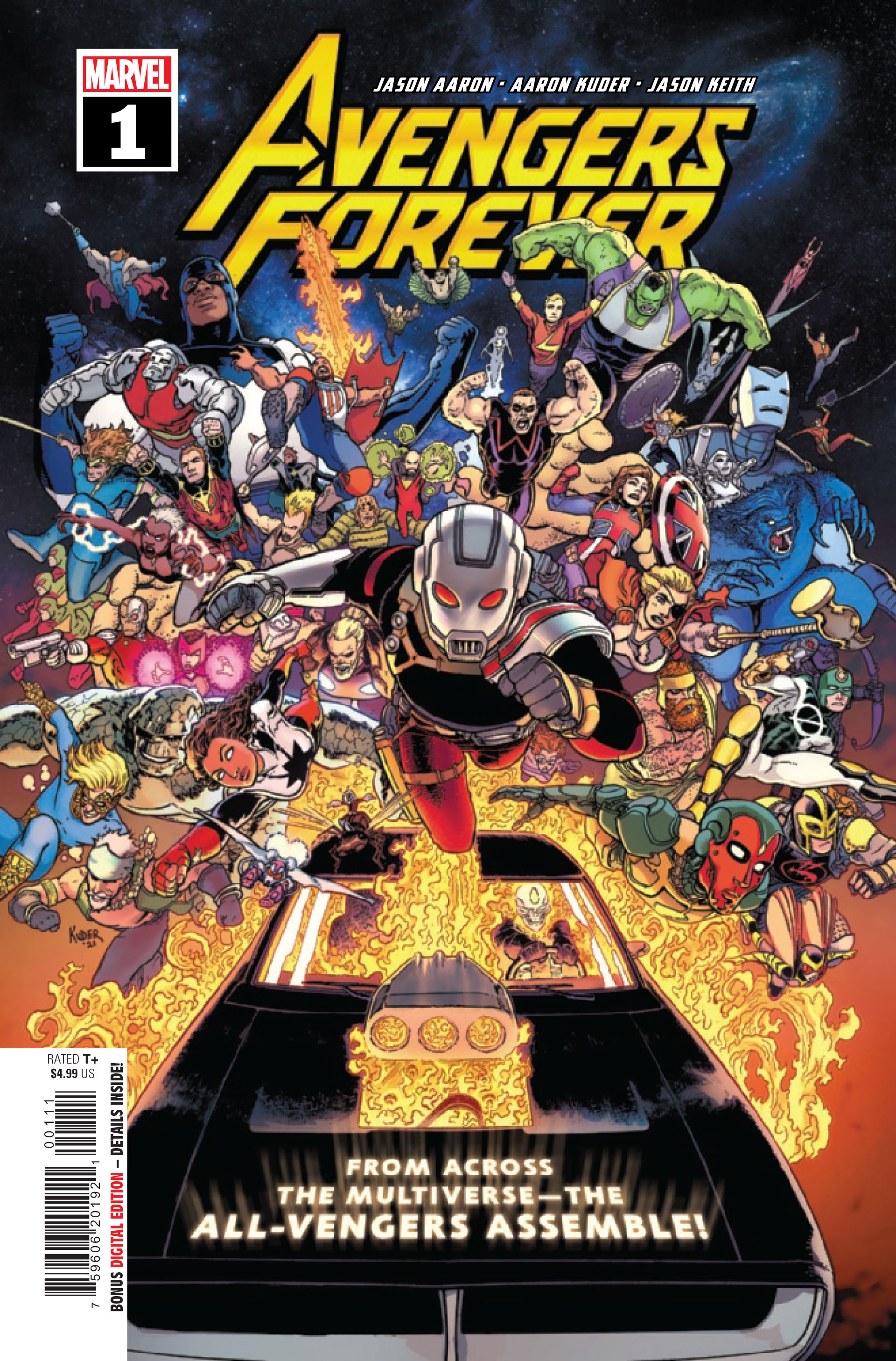

And this trend is spreading. In comic books, Marvel is currently embracing a multiverse model as much as they have since the conclusion of their aforementioned Ultimate Universe line, which collapsed under the weight of its own ballooning continuity - leading to characters such as Miles Morales, the second Spider-Man, to become part of the mainstream Marvel Universe alongside Peter Parker.

Marvel is currently publishing Avengers Forever, an ongoing title featuring team-ups between whole squads of 'variant' versions of popular heroes, and it's also setting up Kang the Conqueror, whose history is chock-full of alt-timelines, alt-identities, and weird continuity puzzles, as one of the Marvel Universe's next big villains.

That emphasis on Kang translates to the Marvel Cinematic Universe as well, which has been almost entirely focused on the concept of legacy heroes and 'Variant' characters since 2021's WandaVision, which overwrote reality and involved two warring versions of the Vision.

WandaVision's follow-up Captain America and the Falcon dove into the idea in a more straightforward way, showing Sam Wilson's path to becoming Captain America (a trick later repeated by subsequent streaming series Hawkeye, in which Clint Barton trains his own apprentice Kate Bishop).

But it's the third MCU streaming series, Loki, that fully embraced the idea of numerous alt-versions of Marvel heroes, specifically Loki, even coining the term 'Variant' that's become common parlance for superhero stories since, and introducing multiple versions of Kang in its finale.

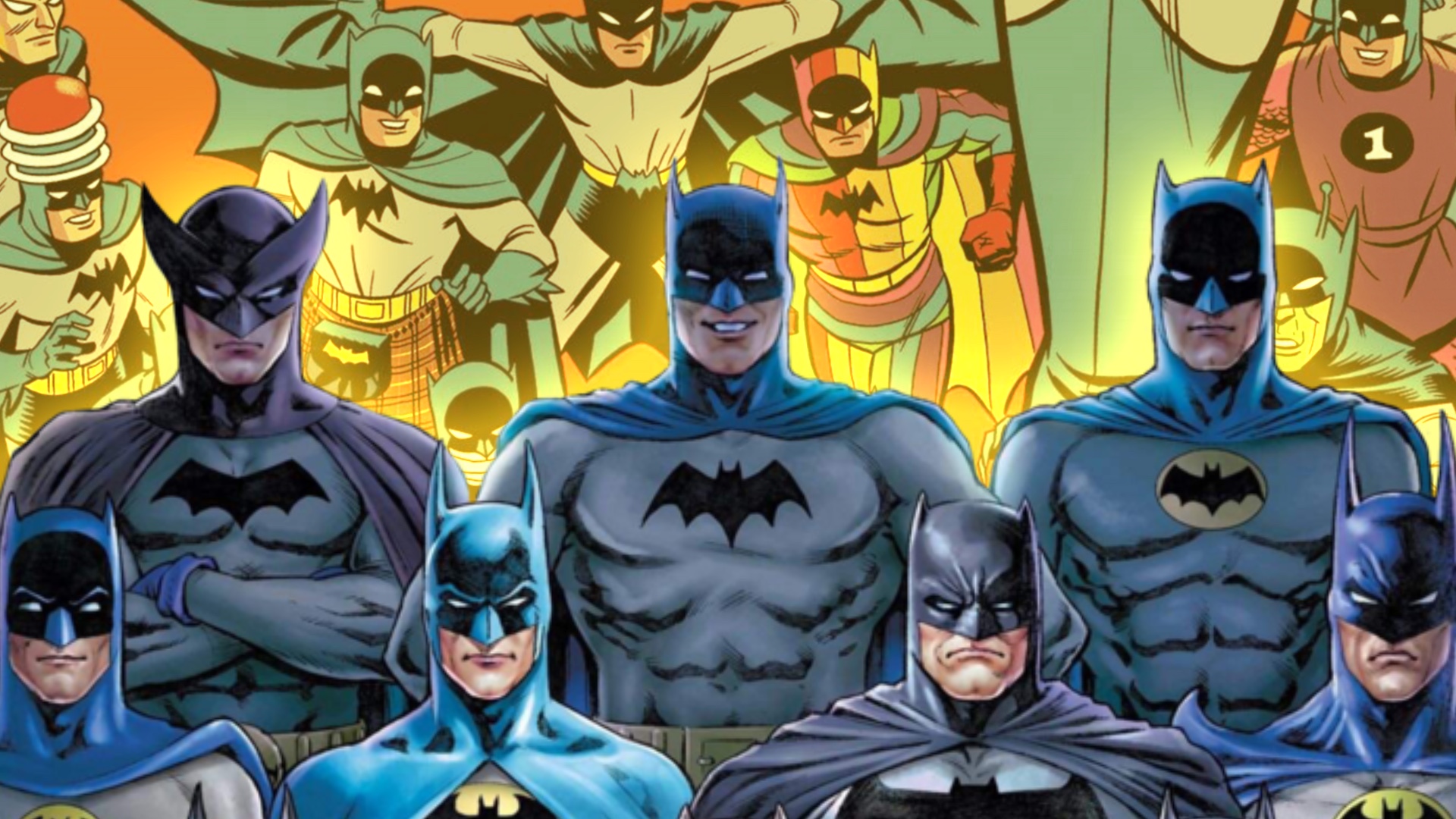

Council of Cross-Time Batmen

At the same time, on the big screen, the current MCU blockbuster Spider-Man: No Way Home features a crossover between multiple versions of Spider-Man from throughout his film franchises, and it's garnered great praise from critics and fans alike - as well as record-breaking box office numbers to boot.

And that will all come to a head in the upcoming Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, which is rumored to again feature multiple versions of heroes we already know - with at least one 'Variant' of Doctor Strange already shown in the trailer.

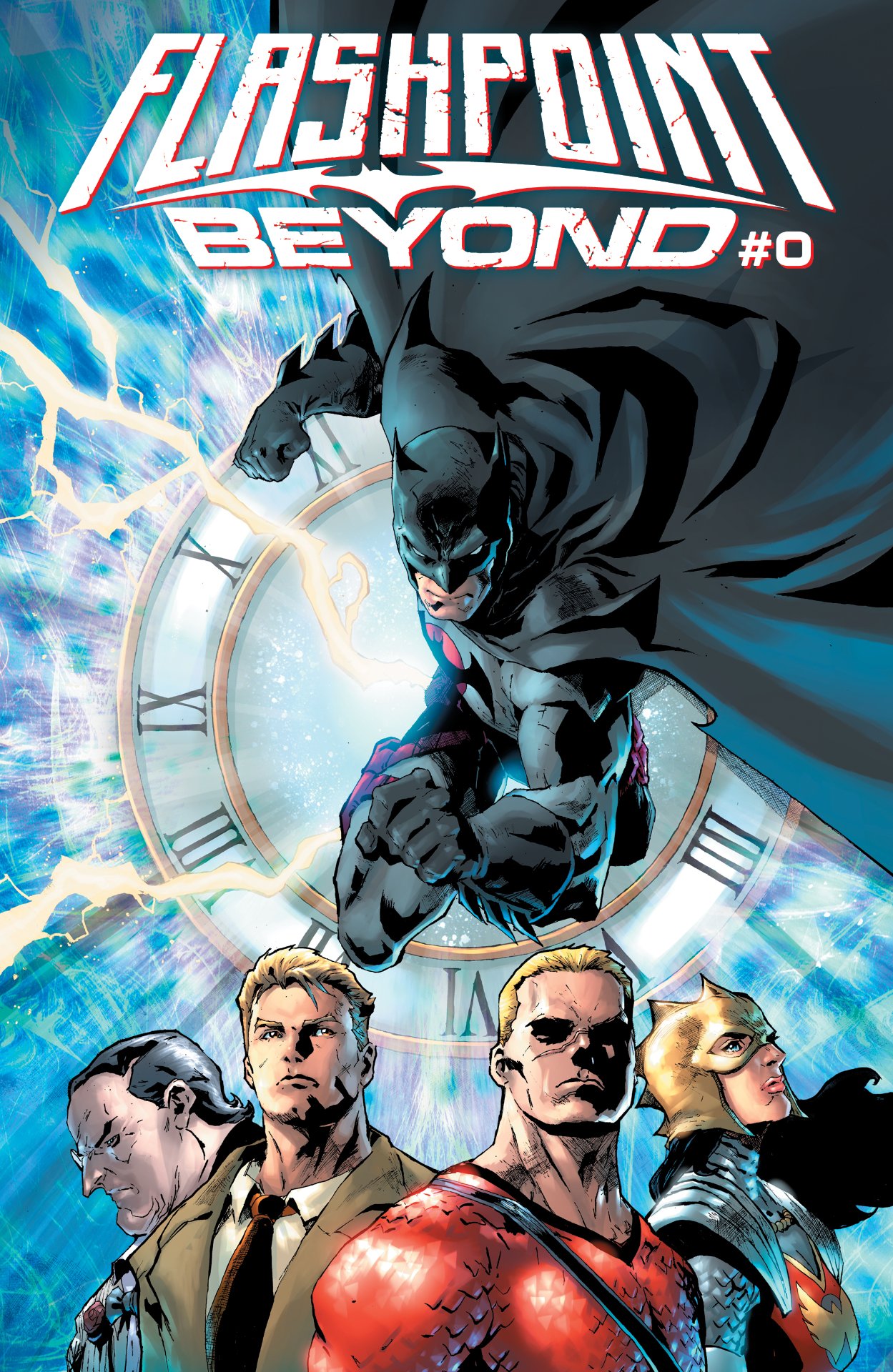

DC's following this cinematic formula as well with who else but Batman, who has enough alt-versions of himself leading their own comic books right now to form a whole team of Bruce Wayne Variants, not to mention his co-Batmen Jace Fox and Thomas Wayne (his own father from an alt-reality who will return in the upcoming Flashpoint Beyond).

Speaking of Flashpoint, the Flash movie, which follows the story of the comic book Flashpoint in which DC's reality was once again remade, will reportedly feature appearances by multiple cinematic versions of Batman including appearances from Ben Affleck's recent version, and Michael Keaton's classic Batman, who himself will stick around to mentor Batgirl in her upcoming movie.

And that's not even mentioning The Batman, which beats Flashpoint to theaters, and which features yet another Batman, played by Robert Pattinson, that won't crossover with other DC properties (yet, anyway) while spinning off its own follow-ups, such as a reported Penguin streaming series on HBO Max.

Modern myths

What this all adds up to is a version of superhero media where everyone gets what they want. Hardcore readers get the satisfaction and intrigue of an ongoing narrative that spreads across their favorite superhero universe (or multiverse, or omniverse), while those who like to pick and choose which stories they buy into or who are coming to the media for the first time have almost as many options to find the version of a character they like best.

And eventually, thanks to the increasingly interconnected and overlapping nature of the current trend of stories that feature multiple incarnations of the same hero, either two separate people sharing an identity or two versions of the same character from different worlds, it's just a matter of time before something happens to make any reader's preferred version of Batman, Spider-Man, or the rest 'count' as part of the bigger tapestry of their shared universe.

To harken back to the concept of superheroes as modern myths, the idea that Batman in his core titles and Batman in his alt-reality titles are separate but parallel characters with similar but diverging stories is no different from the way oral tradition carried myths of old between different cultures, resulting in the existence of both Greece's Herakles and Rome's Hercules, to name a common example.

(And of course, there's a comic book Hercules... and a comic book Thor... and about a million other superhero versions of real mythological heroes, fully taking the reins of the tradition).

Other well-known stories such as the folklore of Robin Hood or the mythology of King Arthur follow similar courses, in which different authors and scholars and even oral storytellers put their own twists on the origins and adventures of the characters they loved. Even in popular modern media, characters such as James Bond are constantly shifting in portrayal, while characters like the Flash have separate incarnations on both TV and movies - and fans have quite easily come to understand and accept those concepts.

In other words, the idea of superheroes teaming up with themselves, and of multiple iterations of characters co-existing in separate but sometimes overlapping narratives, is nothing new in terms of storytelling and hero myths. In fact, the evolving, overlapping nature of storytelling is one of the oldest and most important aspects of cultural story sharing - so in many ways, it's actually about time that superheroes caught up.

Dark Crisis picks up the legacies of some of the best DC stories ever.

I've been Newsarama's resident Marvel Comics expert and general comic book historian since 2011. I've also been the on-site reporter at most major comic conventions such as Comic-Con International: San Diego, New York Comic Con, and C2E2. Outside of comic journalism, I am the artist of many weird pictures, and the guitarist of many heavy riffs. (They/Them)