The Making of Tunic: How the adventure began life in the pages of a notebook

A game made in the margins

Sitting down with Andrew Shouldice, fresh off the back of a double BAFTA win, conversation immediately wanders away from the topic of how this award-winning game was made, and onto the question of notebooks. Shouldice leans over the table to admire ours, a little black Moleskine affair, and it's only after a good few minutes on the relative benefits of stitched versus ringbound that we actually get back to the point at hand. An unexpected tangent, certainly – but one that, as it turns out, speaks to the important role such apparatus played in Tunic's development.

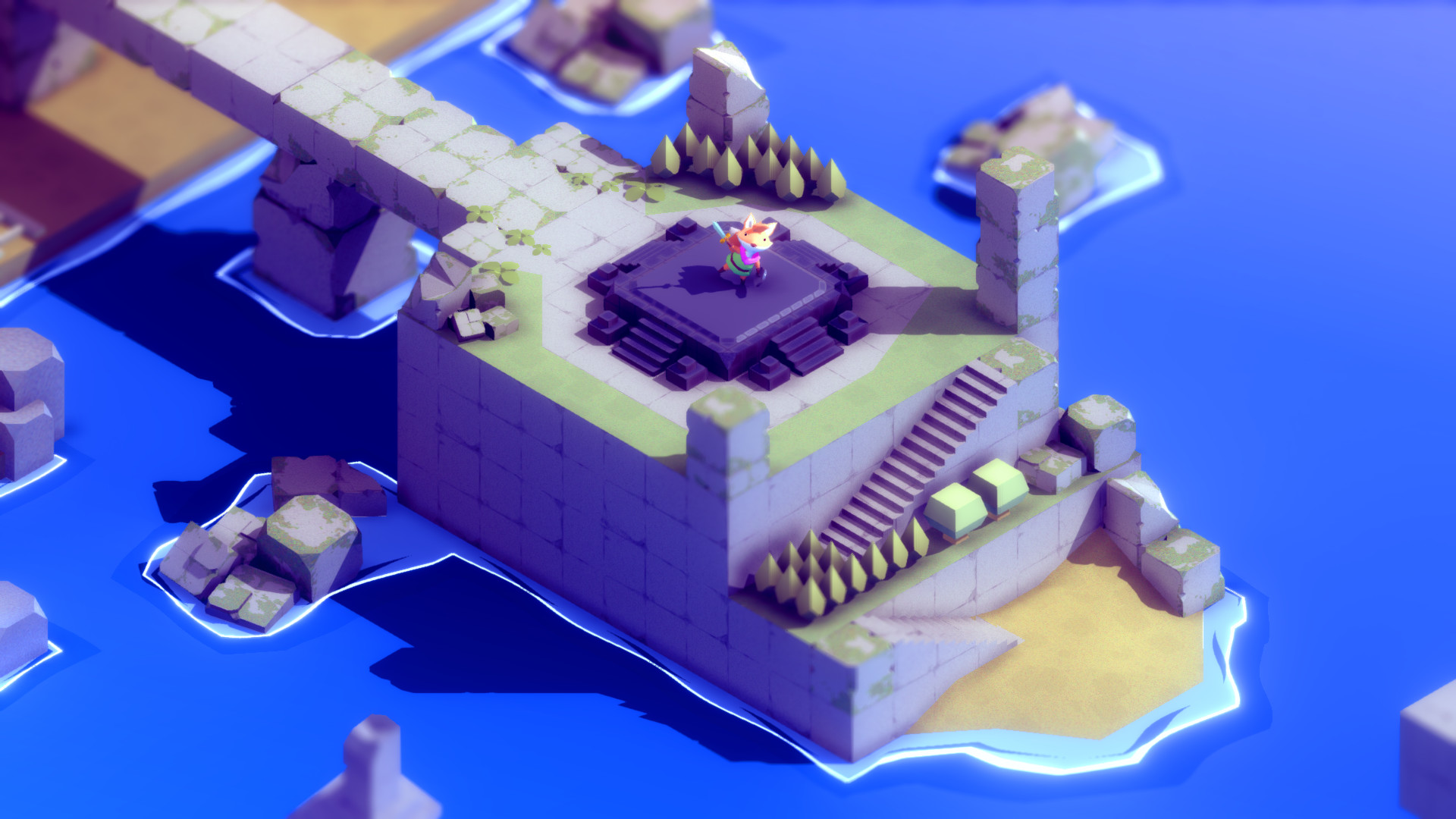

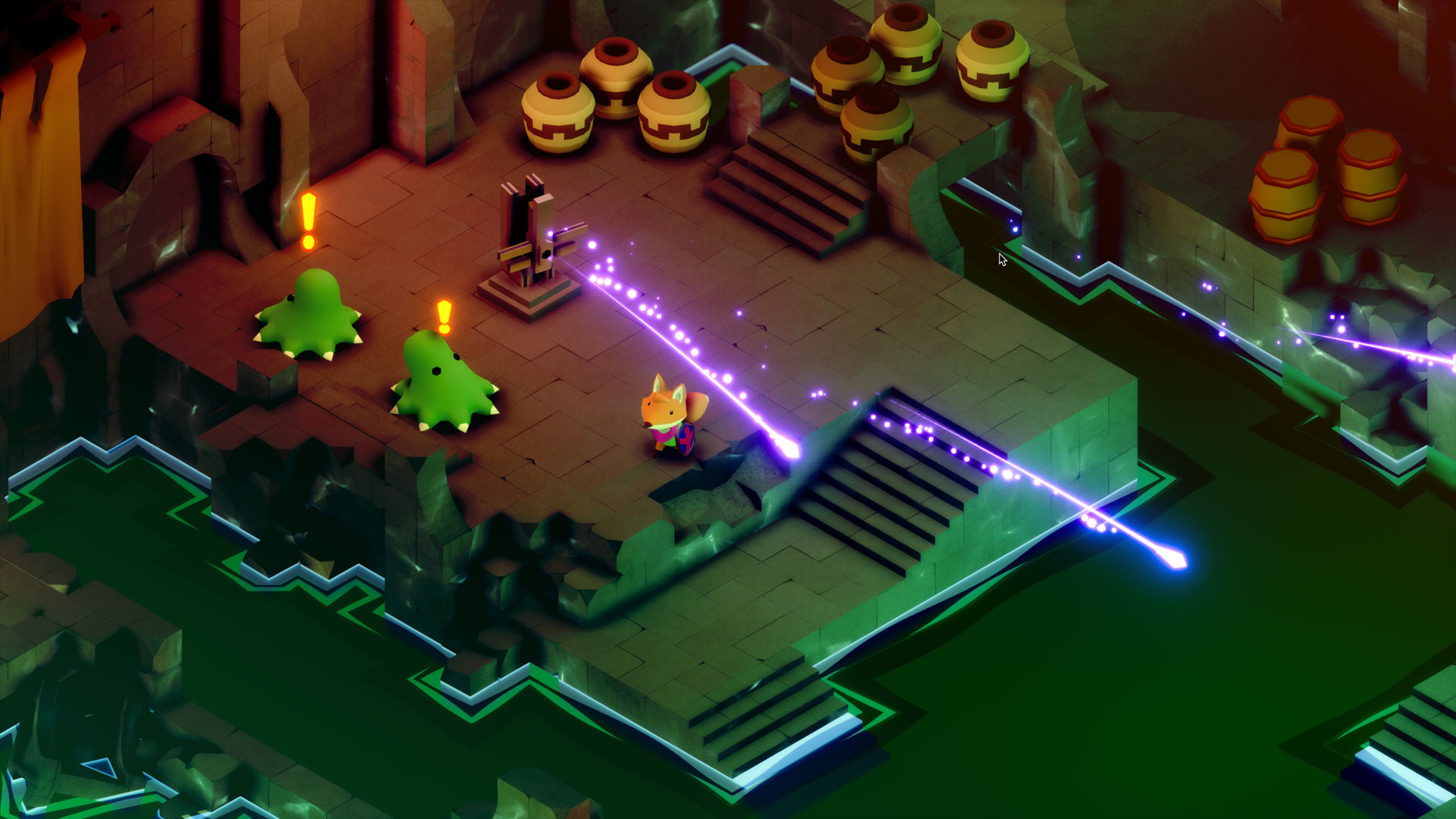

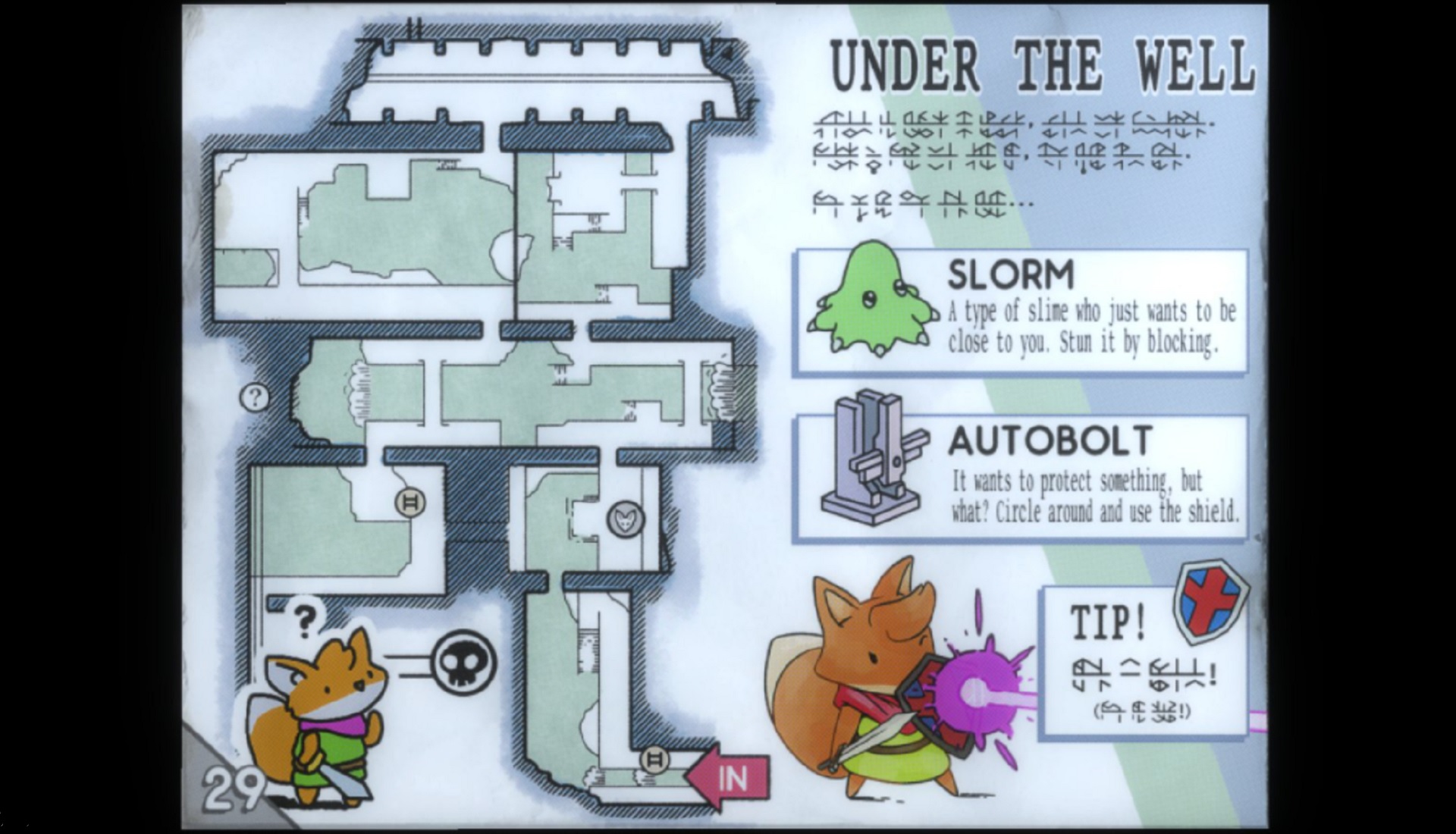

This shouldn't, perhaps, come as a surprise. After all, Tunic makes clear Shouldice's fondness for good old-fashioned paper and ink through its in-game instruction manual. Loaded with beautifully illustrated maps, with hints written in a glyph cipher and biro annotations left by some unseen hand, it feels like a gentle suggestion that you might want to keep your own notetaking equipment to hand, in order to track the game's many secrets, and perhaps even dabble in a little translation if you choose.

Catching up again with Shouldice, now back home in Halifax, Nova Scotia, he produces the notebook that contains the very first inklings of this game, and tells us it dates back to 2010 – five years before Tunic's development began. Not that players would necessarily recognise its contents, he explains: "It's got notes for games that did not end up becoming Tunic. Stuff like, 'What if it was a pixel game where you're just a little guy who's, like, seven pixels tall?'"

As much as any kind of traditional design document, this notebook seems to form a manifesto, as Shouldice attempted to identify an itch that wasn't being scratched by the games he was making in his day job. "I cherish the feeling of getting away with something in a videogame," he says. "Playing something where the story is already written, and I’m just turning the crank or just checking boxes, that can be fun in some ways, if the moment-to-moment is really exciting, but I would much rather feel like I’m really exploring."

Secret Legend

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more in-depth interviews, reviews, features, and more delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge magazine.

Shouldice noted down examples from other games that summoned the magic he was chasing. Super Metroid's wall jump, never mentioned in the manual but available to canny players right from the game's beginning; A Link To The Past's Magic Cape, a hidden item that Shouldice admits even he "always forgets about, that always seems somehow separate [to the rest of the game]". In his notes, needing a quick shorthand to refer to this feeling, Shouldice would occasionally deploy an asterisk-like symbol. If it could be translated in the manner of the game's glyph language, it'd surely say something akin to the name of the project Shouldice quit his job to make: Secret Legend.

The journey from Secret Legend's beginnings to Tunic's release would stretch over more than seven years – but the title change, at least, came much sooner. After leaving his job in the new year of 2015, Shouldice turned up at PAX West the following September with a build he'd spent the summer making at Swedish game development retreat Stugan. He remembers players at the show leaving his stand struggling to remember what the game was called, overhearing mumbled variations on "the fox game" and "secret something or other".

He likens the name change to doing your taxes or going to the dentist – something to be put off for as long as possible. But as painful as it might have been, what the game was called was the least of Shouldice's worries at this point. "There were important questions that weren't answered, that I remember spending a lot of time at Stugan thinking about. Like, 'What is the arc of the game – what is the beginning, middle, end of it? What is the overarching goal? What is the secret goal underneath that?' And those were questions that stayed unanswered – or, like, tentatively answered – for a long time. And that will produce sleepless nights, for sure."

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

As the other Stugan projects began to bear fruit (that year's crop included Tom Francis' Heat Signature and the similarly Zelda-inspired Yono And The Celestial Elephants, both of which were released in 2017), Shouldice found himself stuck in a loop. "It was always a year out," he says of development. "Because a year always felt like an amount of time during which you could get anything done, if you worked hard and applied yourself."

Iteration

"Strictly speaking, though, Shouldice didn't entirely erase all this work. In fact, you can play a version of it yourself in the finished game, hidden away behind a couple of the game's many secrets".

The problem, though, was that Shouldice kept making things and then scrapping them. "Every part of the game," he begins, before correcting himself: the C# script for controlling your character remained throughout, and maybe a couple of early art assets. Otherwise, though, "every area of the game, and most mechanics and enemies and stuff, went through at least two iterations."

Power Up Audio creative director Kevin Regamey met Shouldice via a mutual friend. In that first year of development, Shouldice sent over a short combat prototype. "It was all of five minutes long, just basic targeting and circle strafing and stuff," Regamey tells us. "And then two weeks passed, and he sent us what he called a macro prototype of the overworld. He said something like, 'I'm probably going to throw all this in the trash, but I just wanted to get an idea of what it felt like to adventure, to find secrets, to do the whole Metroidvania thing'." Regamey fired up the new build expecting something of similar scope. Hours later, he was still playing. "Our whole team was like, 'Who the hell is this guy? He says he's deleting the whole thing? There's like a whole game here already. What is going on?'"

Strictly speaking, though, Shouldice didn't entirely erase all this work. In fact, you can play a version of it yourself in the finished game, hidden away behind a couple of the game's many secrets. If you do unearth it, you'll be dropped on the south coast of an island with a striking resemblance to Tunic's true starting area – in part because both are modelled on the original Legend Of Zelda. That familiarity quickly fades, however, as you explore areas with no real equivalent in the finished game: dusty cliffs to the west, a handful of unused enemy types to the east.

This might be the nearest we'll come to experiencing the game as Shouldice does. When he looks back at the game's levels, he says, all he can think is: "There were so many old versions of this that got cut." Does he feel any regret about that? "There was a whole area that got rebuilt so many times. It started out as a desert, then a different desert, then a desert with cliffsides, then a dark forest, then a different dark forest. And then it was just removed. There's a place in the game where it is supposed to go – it just isn't there any more. And I sort of regret that area not being in there. Not because I think it would have been a better game if it was in there; it's just, a lot of time was put into it, and it would have been nice if it that effort was realised somehow."

The upshot of this iterative approach, of course, is that what's left in the game is incredibly dense. "In Tunic, the finished product, if I look at the overworld, every element of it – without making it sound like I'm some galaxy-brain design genius or anything – every part was considered," Shouldice says. "This gate is here because it used to be open, but I decided I want people to zigzag through this area and then open it up to shrink the world a little bit." The isometric perspective is used to tuck hidden paths into practically every corner, many available from the very beginning if only you'd spotted them – and when it comes to the secrets Tunic holds, this is just the tip of the iceberg.

Codes and ciphers

"Now, every time I consider making a secret in a game, and someone says, 'Oh, is that too obscure?' No, it's not!"

Kevin Regamey

While Shouldice mined ideas from his old notebooks, his collaborators contributed some secrets of their own. Regamey is a cryptography enthusiast who once upon a time made Phonopath, a Flash puzzle game that consisted entirely of sound files, challenging players to use audio manipulation, music theory and other skills to find the passwords hidden within. He clocked Tunic's language right from that early build, and spent one sleepless night cracking the code. When Power Up delivered a 30-second sample video to Shouldice in 2015, to show what it could bring to the project, it ended with a screen full of glyphs. "It said, in his cipher, 'Sound treatment by Power Up Audio' – and in the corner, 'Cool game bro'," Regamey recalls with a grin. "It was the first time that he'd ever had to decipher his own cipher."

Naturally, then, Regamey was keen to find some equivalent of the cipher that could be worked into the game's audio. "We landed on this idea of it being musically based," Regamey says. "And I had a lot of different ideas about what that might look like – if it was going to be quarter-[tone]based, or based in rhythm or time, kind of like Morse code but more musical."

The challenge was coming up with something that wouldn't creatively stifle Terence Lee, aka Lifeformed, composer of the game's soundtrack. "It needed to be designed and structured in a way that makes sense with Terence's pre-existing compositional style," Regamey says. "And I knew that Terence loves his arpeggios." His solution took Tunic's phoneme-based language, where each glyph represents a single unit of sound, and converted those into sequences of notes played in ascending or descending order. When you unlock a door, for example, a chime will play that contains the arpeggio for 'key'; others reference phrases you'd only know if you'd decoded the entire manual.

It's a staggering amount of work for what both developers refer to, semi-jokingly, as "content for no one". "We would have been totally fine had players never found this, but they actually found it pretty quickly," Regamey says. "Now, every time I consider making a secret in a game, and someone says, 'Oh, is that too obscure?' No, it's not!" Still, though, the line had to be drawn somewhere. "Someone asked me one time: did you consider localising the arpeggios? Like, making the cipher such that it would accommodate for different languages phonetically? And the answer is yes, we did consider that," Regamey says. "But, I mean, it was seven years in development – we had to ship this thing eventually."

Shouldice credits Finji, the publisher that had signed Tunic early in development, with a lot of patience. "I remember [Finji director] Adam Saltsman coming to me at some point, like, 'Hey, just so you know, in a few months, I'm going to start asking you about the possibility of us beginning to schedule time to think about deciding on a release date'. Very gentle, very accommodating, very respectful of my poor fragile psyche."

The manuel

Over the course of development, Shouldice had learned to work "sloppy and fast", knowing that he was likely to end up rebuilding anything he made. It's less painful to scrap "garbage", he says – the trick is to "keep it in the garbage phase for as long as possible". In the last few months, it was a case of pulling everything together into a polished final product. And so Shouldice figured out what tasks were remaining ("all these important features that just didn’t exist yet"), estimated how long each would take, and created a spreadsheet named 'Tunic Content Complete Before Andrew Turns 36'.

Surprisingly, given how pivotal it is to the game, the manual was saved for last. "The game came out in March – we were still working on manual pages in, maybe, January." Its contents existed before that, but only as rough sketches, with just enough detail that playtesters could follow along. "Because things were gonna be in a state of flux, much like geometry of the overworld, it made sense to keep it extremely rough," Shouldice says. It was a "risky" choice, he admits, but it worked out – and it's how he wishes he'd approached development from the start.

"I don't know if this is good advice, but this is the advice I am giving myself after a seven-year project: be sketchy, when you need to be sketchy. Because one of the main reasons the game took so long was trashing work that I spent too much time on, when I shouldn't have." So, as his mind starts to turn to whatever's coming next, will he apply that thinking to development of his next game?

"I think the fact of the matter is, as good as it would be to keep that philosophy in mind when working on a new project, in the end game design is always sort of reinventing the wheel. Games are about novelty – you want something that is new and fresh, otherwise you can just play the old one."

If he were simply to make "another game like Tunic, where there's action-adventure and fighting and a bunch of secrets," he says, "most of the good ideas are in the game." Shouldice has emptied all his notebooks, at least of the ideas that fit this framework. He doesn't seem to know yet where he's headed next. But it's hard not to suspect that somewhere within all those idea-filled pages, there's an answer just waiting to be found.

This feature first appeared in Edge Magazine issue 386, which you can pick up right now here.

Alex is Edge's features editor, with a background writing about film, TV, technology, music, comics and of course videogames, contributing to publications such as PC Gamer, Official PlayStation Magazine and Polygon. In a previous life he was managing editor of Mobile Marketing Magazine. Spelunky and XCOM gave him a taste for permadeath that's still not sated, and he's been known to talk people's ears off about Dishonored, Prey and the general brilliance of Arkane's output. You can probably guess which forthcoming games are his most anticipated.