7 ways that Netflix's Bodies is different to the original DC comic

Comparing and contrasting the DC Vertigo comic with the hit streaming show

Bodies has been a huge hit for Netflix. The new science fiction-tinged murder mystery takes place across four time periods and follows four very different investigators as they try to unravel the mystery of a series of identical corpses that appear in the same location in every time zone.

The series is based on a fascinating eight-issue 2014-2015 DC Vertigo limited series written by the late Si Spencer and drawn by Phil Winslade, Dean Ormston, Tula Lotay, and Meghan Hetrick.

While the basic plot is similar to the TV show, the tone and some of the choices made are radically different. So join us now as we break down seven of the biggest things that the TV show changed from the original comic.

It should go without saying that we will be discussing major plot points from both versions of the story in great detail here, so consider this your first and last SPOILER WARNING, but know you are loved.

The murders go back much further

In the TV show the first body is found in 1890. That's also the earliest time period shown in the comic, but as DS Hasan discovers in the course of her investigation, there's also a much older body. We learn that an ancient corpse has been preserved in a peat bog for about 3000 years.

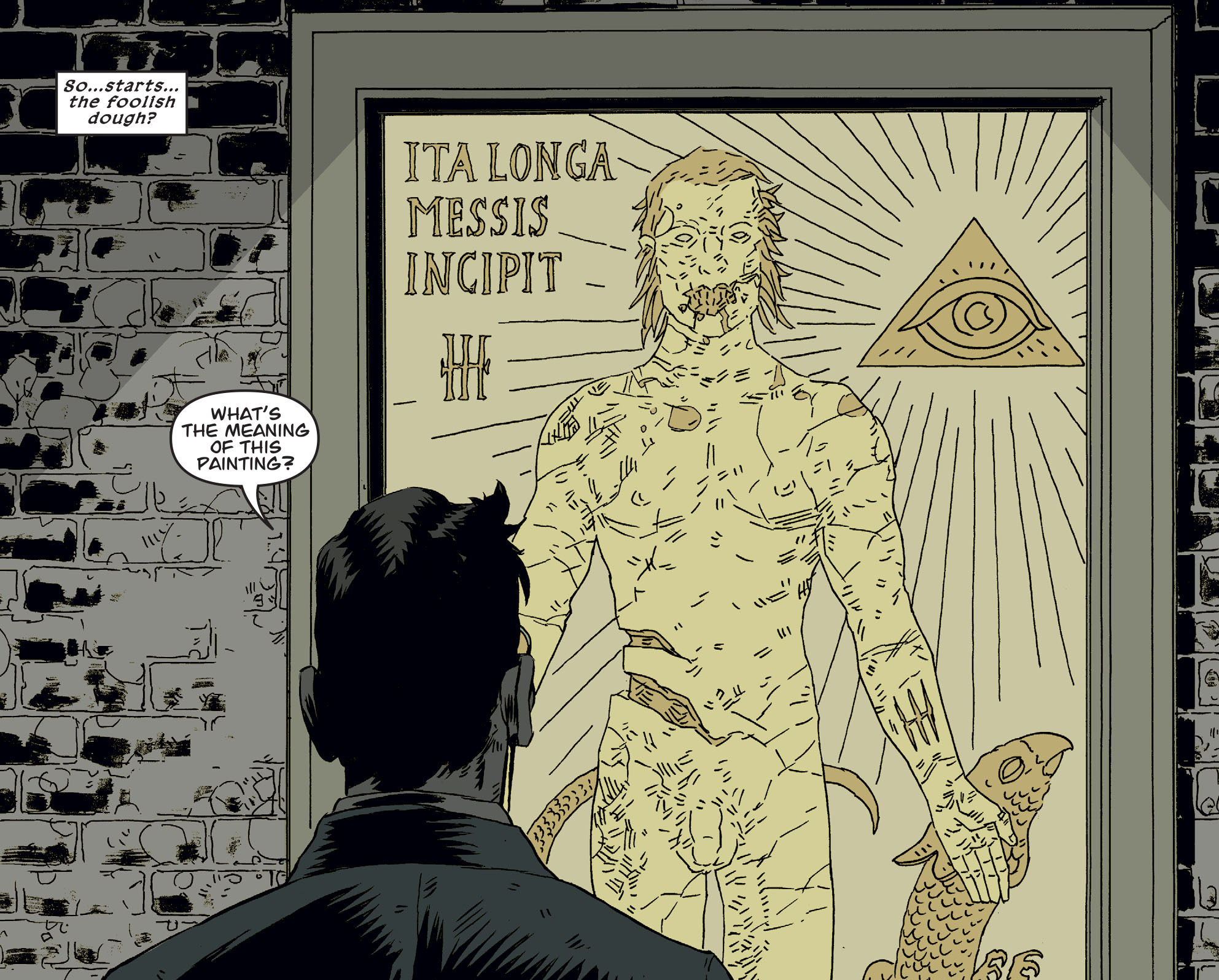

Meanwhile, Inspector Hillinghead discovers a painting from the 14th century of the same corpse hanging in the British Museum, with the inscription, "And so begins the Long Harvest.". Where were the bodies found? Longharvest Lane of course.

DS Whiteman is a real piece of work

DS Whiteman in the series, as played by the superb Jacob Fortune-Lloyd, is initially a fairly dislikable figure and one who is certainly not afraid of breaking the law to get his way. Still, he softens as the show goes on, especially when he forms a bond with young Esther (Chloe Raphael) whose life he tries to save, only for her to later be murdered. By the end of the show he's the character who has arguably gone on the biggest emotional journey.

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

Whiteman in the comic is entirely different, with none of his TV counterpart's redeeming features. Although they share the same backstory, this Whiteman (birth name Karl Weissman) is a gangster and an unrepentant killer who murdered his niece Esther in cold blood and who gleefully tortures his enemies. At one point he glibly says, "Karl Weissman looks after number one - let the whole world burn for all I care". Yep, that pretty much sums him up.

Elias Mannix does not exist

Whether he's going by Elias Mannix or Julian Harker, the character played by Gabriel Howell and Stephen Graham is at the heart of the TV show's plot. His plan to remake the world in his own image is central to everything that happens in Bodies - so it's pretty wild that he's not in the comic at all. There's a spiritualist called Henry Harker, but they are not the same character.

Instead, the motivating factor that links the multiple time zones of the comic is the recurring corpse that appears in each time zone. Don't worry, we'll get to him in a moment.

Future London is entirely different

On TV Iris Maplewood lives in a future London rebuilt following the nuclear attack in 2023 and ruled over by Commander Mannix. Visually it looks clean, stable, safe - but it's very clear that this is a pretty dystopian vision of the future.

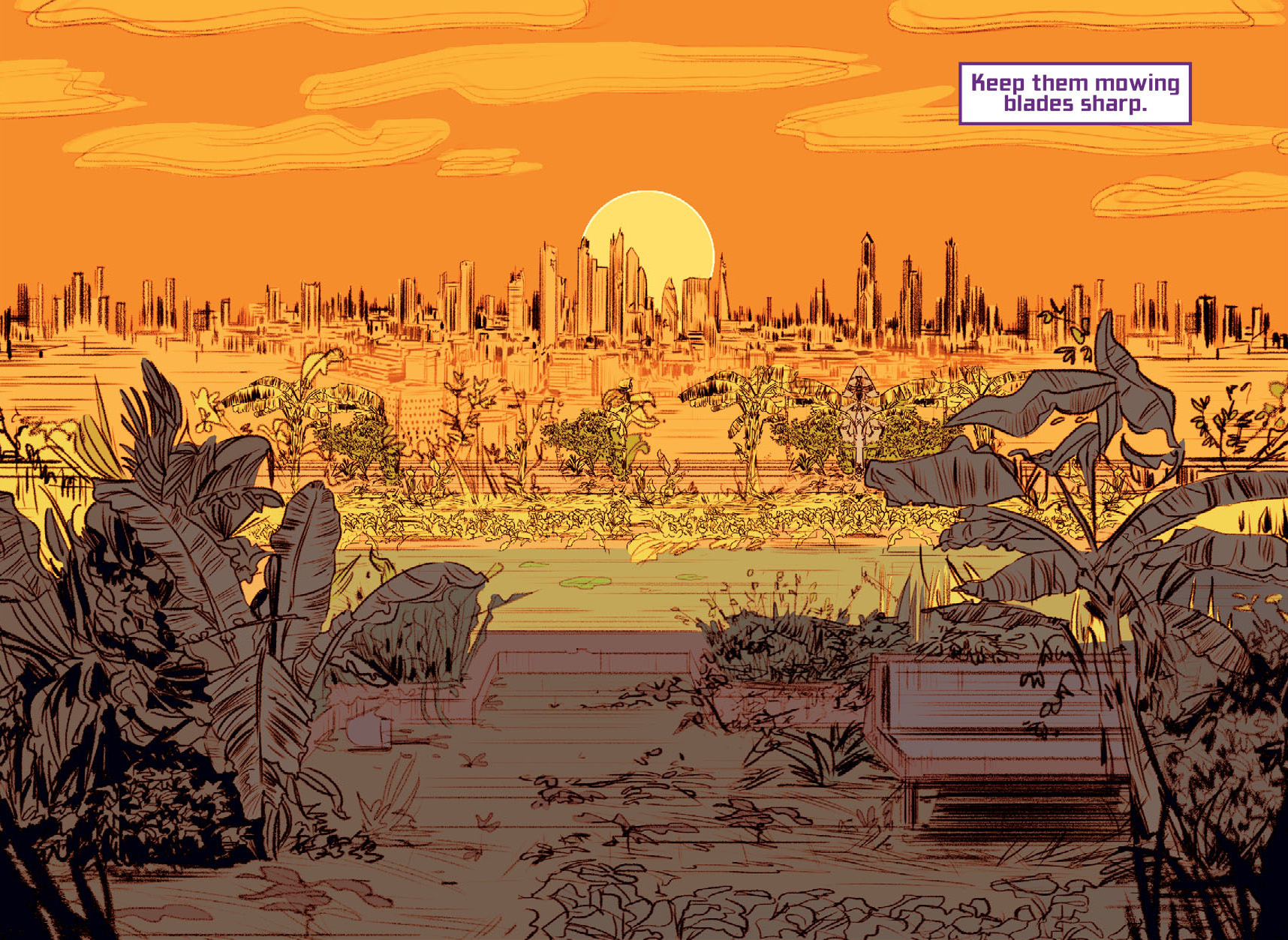

In the comic Maplewood still lives in London, but there's been no nuclear attack here. Instead, in this future a mysterious "pulse wave" has turned most of the surviving population into amnesiacs. The sky is also a permanent and unsettling shade of yellow.

In Bodies #7 we learn that Maplewood's mother was one of a team of scientists at KYAL Research who were experimenting with the dangerous pulse wave, using live human prisoners as their test subjects. Iris is furious and tries to intervene but ends up accidentally activating the pulse wave herself, causing the disaster. Whoops.

Time travel is not really a thing

Although the mechanism of how time travel works in the TV show is vague, we know that it has to do with the "Deutsch Particle". The older Elias Mannix uses a machine bafflingly called The Throat to travel back in time to 1889 where he steals the identity of the dead Julian Harker, wins over the dead man's mother, and begins (in a chronological sense) his plan to change the world that will eventually come to fruition when his younger self detonates a nuke in 2023. Got that? Good.

In the comics, however, time travel in the traditional sense simply doesn't exist. The only person who moves throughout the different time periods is the mysterious entity known as "Frank" - the body that keeps showing up. We should probably try and explain who that is now...

That's not Defoe's body...

Let's address the body in the room - or rather in Longharvest Lane. This is possibly the most significant change made for the screen and it gets to the heart of all the major differences between the two versions of the story.

In the TV show the bodies belong to the time-hopping scientist Gabriel Defoe. He is travelling into the past in an attempt to prevent Mannix's nuclear attack when Maplewood (at that time still more-or-less loyal to her Commander) shoots him in the eye. His body is splintered across time setting this whole mystery in motion.

In the comics the body is revealed to be that of a supernatural being who goes "by many names" but prefers to be called Frank. He exists throughout history appearing at different points and, well, murdering himself.

It's pretty complicated, but this is how he explains it to Whiteman: "For the briefest of times, there are two of us, arriving in tandem in the sacred place... the slayer and the slain, unwitnessed, unknown. And when the death rattle sounds, only one remains - the victim."

That implies that Killer Frank simply blips out of existence while Victim Frank's body is then found by an investigator (Hillinghead, Whiteman, Hasan, Maplewood, whoever) before later resurrecting. It's a cyclical cosmic self-sacrifice intended to effect change in people and the world.

In the comic Frank's actions force Hillinghead to accept that he is gay, allow Maplewood to undo the effects of the pulse wave, and lead to Hasan being promoted, which in turn allows her to stamp out the racist hate groups in London. Whiteman's fate is rather bleaker, due to his dreadful actions over the course of the comic.

Jack the Ripper is in the comic... kind of

Hillinghead encounters Victorian London's most infamous serial killer late in the comic, or so he thinks. In fact this appears to be one of Frank's tricks combined with a jar full of tentacles. The Ripper is distinctly absent from the TV show.

So, there you have it. The Bodies comic is altogether weirder and wilder than the Netflix show, but both are thrilling and fascinating stories in their own right. If you've seen the show then it's well worth seeking out the comic to see where it all started and enjoy some gorgeous art and witty dialogue. And handily it's getting a much-needed reprint in just a few days.

Bodies is streaming now on Netflix. The original comic by writer Si Spencer and artists Phil Winslade, Dean Ormston, Tula Lotay, and Meghan Hetrick, is republished by DC Comics in trade paperback on October 31.

Bodies is available to watch now on Netflix. For what else to watch on the streaming platform, check out our guides to the best Netflix shows and the best Netflix movies too.

Will Salmon is the Streaming Editor for GamesRadar+. He has been writing about film, TV, comics, and music for more than 15 years, which is quite a long time if you stop and think about it. At Future he launched the scary movie magazine Horrorville, relaunched Comic Heroes, and has written for every issue of SFX magazine for well over a decade. His music writing has appeared in The Quietus, MOJO, Electronic Sound, Clash, and loads of other places too.