How Marvel's Spider-Man 2 gets to the heart of the character in a way the MCU films can't

Opinion | Insomniac's latest is packed with break-neck superhero action – but its quieter, human moments are just as important

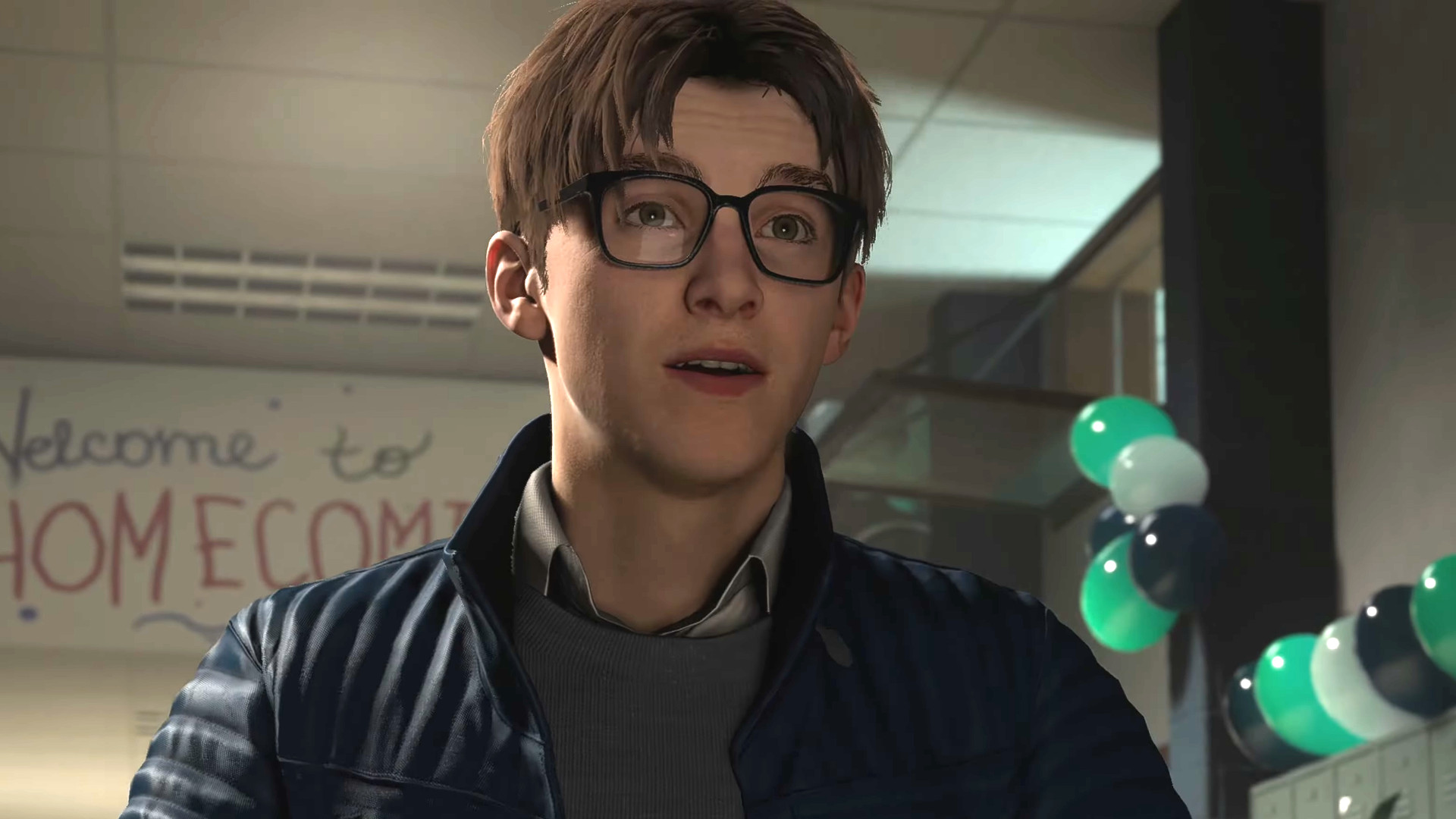

In between the mass brawls with evil henchmen and the epic battles against Venom, Kraven and other villains of comic book lore, there are a lot of quiet moments in Marvel's Spider-Man 2 that are perhaps unexpected. Think about the long nostalgic scene where Harry, Peter and MJ visit the Coney Island amusement park and lark about on a love testing machine. There's Miles stressing over his university application and having to meet his mother's new boyfriend. The whole section where Harry and Peter visit their old high school, reminiscing about their friendship. And that funny bit with Peter frantically tidying his half-empty house before MJ visits.

There were similar moments in the original Marvel's Spider-Man and Miles Morales titles too, and while it's tempting to write them off as palate cleansers between the big fights, that's not what's going on here at all. It's these important sequences that show how much Insomniac understands the source material, and why the games get closer to the Spider-Man comic books than the MCU movies ever could.

Unmasked

On the Radar: Marvel's Spider-Man 2 – A deep dive into the much-anticipated superhero sequel

When Stan Lee and legendary artist Steve Ditko first conceived Spider-Man in the early 1960s, it was an era of huge change. Teenagers were gaining more financial and social independence in the post-war world, their lives and problems were being explored in TV shows and pop music in ways they never had before. Lee and Ditko wanted a hero who spoke to this new teen demographic – a hero who was young, awkward, a little bit nerdy, and beset with worries over girls and money. The launch of The Amazing Spider-Man issue one in 1963 was the first time an adolescent hero had led a major comic book instead of being consigned to sidekick status, and Marvel wanted to explore that aspect of his identity. He had more in common with the cast of the hugely popular Archie comics than he did with other superheroes.

In many ways, the original Spider-Man stories were more like soap operas than typical superhero adventures. Peter's interior life was as important as his web slinging antics, the ups and downs of his relationships with Aunt May, MJ and Gwen Stacy were central to the plot lines. Look at some of the most iconic Spider-Man covers: his marriage to MJ in 1987 (the comic is even billed as a Special Wedding Issue), the death of Gwen Stacy, the classic issue 75 image of Spider-Man stumbling down an alley, lost in grief. These are vital beats in the Spider-Man story. The approach was hugely successful, broadening the audience beyond children, appealing to teenagers and twenty-somethings who engaged with the relatable personal stories.

This element came to the fore when artist John Romita Sr took over from Ditko in 1967. Romito Sr came to Marvel after seven years at DC drawing romance comics with titles such as Young Love and Our Love Story. He brought this sensibility to Spider-Man, working with Lee to introduce Mary Jane in issue 42 and making that relationship a key element. From 1977, Romito Sr also drew the wildly successful Amazing Spider-Man newspaper strips, which ran for 40 years in a number of publications. Discussing those stories in the book Comics Creators on Spider-Man, Stan Lee said: "I would pace the strip like a soap opera and focus on Peter Parker. I would include super-villains and give the strip a real Spider-Man feel, but try to pace it like [Newspaper soap opera strips] Mary Worth or Rex Morgan."

"We're so used to seeing grounded relatable comic book characters now, we forget that Spider-Man came into a world of God-like superheroes and fictitious mega cities."

While the films simply don't have the time or space to really explore Spider-Man's relationships beyond a few cute scenes, the games really build on them. Over the 30 or so hours of Marvel's Spider-Man 2 (the equivalent to several months of TV soap opera episodes), we get a full arc of Peter and Harry's relationship breaking down and recovering; we get Miles's self-doubt explored in multiple scenes and moments, as well as his love of the Harlem community he lives in and the stories that surround him there. This isn't just backstory, it's crucial to the main narrative of the game. It's Miles's self-doubt that the villains in Spider-Man 2 exploit during boss battle sequences. Peter's love of MJ is exploited by Venom in one of the most emotionally gruelling fight scenes in superhero gaming history.

We're so used to seeing grounded relatable comic book characters now, we forget that Spider-Man came into a world of God-like superheroes and fictitious mega cities. He was a direct challenge to that, a scrappy kid in a dodgy neighbourhood – the world outside your window, as Lee used to put it. The Marvel movies understand his youth, his friendships, his home life, but it's the games that really explore those elements in the way Lee and Ditko intended. There's a whole story at the beginning of Marvel's Spider-Man 2 about Peter getting fired from his job as a teacher, and how concerned he is about paying the rent, and it reminded me of another Lee quote about Spider-Man: "I wanted to write about a character that worried about money – just like I did."

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

So if you raced through Marvel's Spider-Man 2 concentrating on the climactic boss fights, the street crimes and the raids on Hunter bases, go back and play again. Do the emotional side quests, listen to the dialogue – notice how a lot of the stories play out over multiple hours, just like soap opera plots. This is the stuff of Spider-Man, as much as the explosive battles with Venom and Kraven. This is who Peter and Miles are.

Check out the best superhero games saving the (virtual) world right now

Keith Stuart is an experienced journalist and editor. While Keith's byline can often be found here at GamesRadar+, where he writes about video games and the business that surrounds them, you'll most often find his words on how gaming intersects with technology and digital culture over at The Guardian. He's also the author of best-selling and critically acclaimed books, such as 'A Boy Made of Blocks', 'Days of Wonder', and 'The Frequency of Us'.