Launching a new studio with former Forza Horizon and Codemaster devs is like "taking the best singers from the best boy bands in the world," says studio head

Interview | A trip through the Collected Works of simcade savant and Lighthouse Games studio head Gavin Raeburn, who has made a habit out of revolutionizing a genre

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

To the benefit of every racing-game fan in the world, in the early '80s a young boy in England's north east stared at the pixels on the screen of an arcade cabinet and became fixated on discovering how they worked. Today, Gavin Raeburn has as impressive a credits list as anyone in game development might hope to amass, as producer on seminal Codemasters titles such as TOCA and Colin McRae, and as studio head and game director on the Forza Horizon series from its point of origin to the juggernaut Horizon 5 in 2021.

Having left Codemasters in 2010 to co-found Playground Games, Raeburn has recently embarked on that same high-risk move again, leaving the Forza maker to form Lighthouse Games. Launching the new venture, he said that "all the best people I've worked with at Codemasters and Playground" were joining him, likening it to "taking the best singers from the best boy bands in the world".

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more in-depth features and interviews on classic games delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge or buy an issue!

Lighthouse's first project is still under wraps for now, but it's clear that Raeburn remains as enthusiastic about the industry today as he was when he started out, a period he remembers with fondness. "Computing in the very end of the '70s to early '80s, there was something about it that was magical," he reflects. "It was a portal to another world in a time when there was no Internet, no digital anything." In the interim, an entire industry has formed and reformed, the genres within it shifting to match escalating demands for fidelity, immersion and innovation. With Lighthouse now fully formed and its debut game well under way, the stage is set for Raeburn to once again challenge and change the definition of a racing game. Back in 1987, however, all he had was a hardback book about coding, a homebrew Commodore 64 project, and a stack of hopeful letters to publishers…

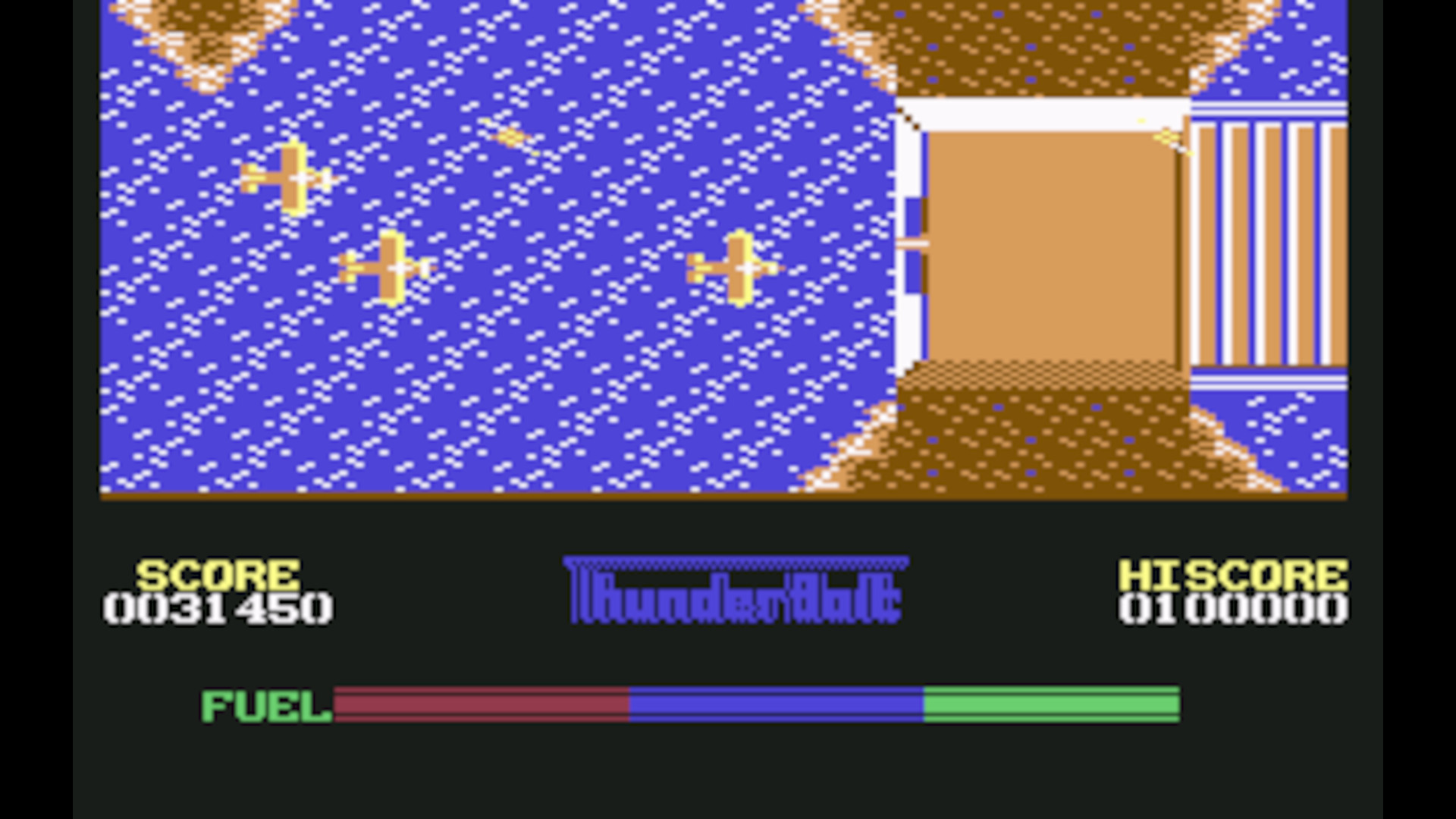

ThunderBolt (C64, Codemasters, 1987)

I loved the whole process of just getting something together and moving on to the next thing. It was always the next idea that was driving me forward. But the quality of the games I was building – technically, at least – was getting better.

Thunderbolt was the first game that I made as a package. It was pretty decent. It had decent music. Technically, it was strong. Well, the game design was what it was, but as a package, it worked. And it was in the vein of lots of other scrolling shooters at the time – so I was just trying to see if I could make a scrolling shooter. Now, as was the case back in the day with all the games that I built, I would look at the back of gaming magazines, just find companies to send these off to. And I had a pile of rejection letters when I was 14, 15, 16, as you might expect. But then that started to change. I sent Thunderbolt to Mastertronic and also Codemasters.

Mastertronic came back to me first and they said, "Wow, we'd like to publish this – we'll offer you £2,000." I think I was 17 at the time. That was astonishing back in the '80s. I couldn't believe it. I thought, "Right, yeah, I'll do that. Let's go." But then the Darlings came back. David Darling says, "Right, well, we'd like this and we'll give you £3,000 for it."

So it was sold to Codemasters and that was my foot into Codemasters, which really was the start of my career. And I remember going down to pick up the advance cheque for that game and to say hello to the Darlings down in Leamington Spa. I went to their farmhouse, as it was then, and I remember seeing David Darling in his MR2 in the distance just driving towards us. As he pulled up, he was waving this cheque out the window.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

TOCA: Touring Car Championship (PC, PlayStation, Codemasters, 1997)

We could visit all of the local circuits – I wanted to get as accurate circuits as I could.

I wanted to make it authentic. This is when PlayStation had just come into being and it was all new. It was astonishing. It was a real period of learning about new technology and creating new techniques. That was what really gave me the buzz at the time. With TOCA, obviously it was a licence of a British motorsports series. A lot of the design was done for you, so it was the authenticity we wanted to get into that game – just translate what you saw on the TV. I was not into driving games too much at the time, but what I loved about the BTCC [British Touring Car Championship] was that it gave me what I didn't see in other driving games. Other driving games were really clean. There were no mistakes. It was all timing-based. But here was BTCC where collisions were not frowned upon, damage was not frowned upon. Close racing – it was the excitement of that.

I think trying to transcribe what we saw, and the fact that it was a British series, helped as well. We could visit all of the local circuits – I wanted to get as accurate circuits as I could, so we used Ordnance Survey. We went all the way down to visit them, and they could provide us with accurate, detailed height maps of the tracks. So, even on the PlayStation 1, with the few polys you had, we could get that in, and it did translate reasonably well. You got some of the bumps where people would expect bumps to be; the hills were correct. Car physics was a different thing, though. Back in the day, you couldn't have physics for every single tyre. So, I think for the main player car, we had two-point physics. You had one point that had to represent the front axle, and the back one of the tyres. And for the AI, you only had one point. It was as simple as that, and even then it was a struggle. So it was a fine balance between trying to offer something that was authentic but still playable. And it was an ongoing battle. You know, the cars would spin out too easily. You have to find that fine line between risk and reward. I think we just about got there. But it was a hard game, looking back. I think all of my early driving games are too hard. Maybe that was OK for the audience then, but I would have made them a lot easier, I think, certainly if they were released now.

TOCA 2: Touring Cars (PC, PlayStation, Codemasters, 1998)

You're never quite sure how long a licence is going to last in the public's eye. Not the game, but the actual sport itself. We can't just offer what players have seen before because it's largely the same tracks, largely the same cars and drivers. We need to do something else. And that's where we started looking at the support series, again with very limited budgets.

Team sizes were growing, complexity was growing. TOCA 2 was not that much different to TOCA 1 except that we had the learnings that a car takes this long to build; a track takes roughly this long. But again, without prototyping, when you're injecting new ideas and new techniques, that will always cause problems, and it continued to do so. But after that we moved on to Microsoft Project, which helped a lot. But Microsoft Project is really built for building ships and motorway bridges and houses – it's not meant for what we do with videogames. There's no flexibility built into it, so that continued to be a challenge for us, I would say.

For good or for bad, [there was a rivalry between the TOCA and Colin McRae teams]. I'm not sure it was good, but the way Codemasters was set up, they liked teams to try and better each other, and I think, well, that's fine. There was definitely rivalry there over the years, but both games did well. They were both successful, so the winner was Codemasters.

Throughout the '90s, Codemasters were doing better and better. Colin McRae was just knocking it out the park. TOCA was knocking it out the park. They still had Micro Machines. They had lots of wins, and the old model of basically giving full autonomy to the individual teams to build what they wanted still worked. That was the model that they started with at Codemasters. The problem later on, of course, was that, when those projects failed, the budgets were larger and had a much bigger impact on Codemasters.

TOCA Race Driver (PC, PS2, Xbox, Codemasters, 2002)

Every generational leap offered challenges, but on the upside, things like physics could get a lot better because the base power was there.

For Race Driver, we'd moved to the next generation. Every generational leap offered challenges, but on the upside, things like physics could get a lot better because the base power was there to allow it. Essentially, all of these driving games were another game in a long series, so you're learning things from just the nature of driving, having cars in a field and also the game design which you want to evolve as well. I think TOCA Race Driver was that. [Previously] the success we had was that we gave people a reason to race, a reason to want to drive. You had naturally great opposition. There were certain drivers, opposing drivers, that were very skilled and they became almost entities within themselves, and we wanted to expand upon that in the next Race Driver series. So, one [way to do that] was to add a narrative, to give a purpose for why you were driving. Not just: 'Here's another race, here's another car – off you go'. It was: 'This is why you're doing this; this is what you're trying to achieve', and that worked to an extent. I think it was another learning process, and the game design as well was about giving choice as you progress through the championship rather than just doing the next single race. We knew players liked to do different types of racing – some people might want to race their trucks, and one might rather be in a touring car. So we always gave those options as you were progressing through the career structure.

We did it all ourselves. We did all the auditions. We found the actors, we wrote the scripts – with help from others, I think – but that was relatively straightforward. But just the basics of getting FMV into the game at the time was still quite challenging. Even things like lip syncing was quite a challenge. Just putting the FMVs together and storing them on the disc was quite complex.

Colin McRae: Dirt (PC, PS3, Xbox 360, Codemasters, 2007)

Colin McRae as a series had been falling off. They weren't selling quite as well, so there was a desire to try and do something new. We needed to broaden the audience. I thought, 'Let's not just offer rally – let's offer rallycross and a few other components as well'. And that did work. The choice was there as well with the first Dirt, with the [Career Mode] pyramid, which gave a lot more meaning to the progression through the game. So they did work well, along with the improved physics. We had a dedicated physics engineer as well, which helped.

For Dirt, [our headcount was] probably around 50 or 60. Codemasters was growing in size, and we developed games like Dirt and Grid in about a year. I think for Colin McRae: Dirt it probably took a little bit over a year. It's all very, very compressed. You're learning a lot. You're moving forward at quite a pace, and with console generational changes back then, you were looking at fivefold increases, sixfold increases in power. Now you're lucky if you get twice the power. It's definitely slowed down.

I was really keen to push forward the realism. That was a driving force, and then the design became increasingly important as the technical limitations started to fall away. We looked more towards the design and the immersion of the player, and that really came to pass with Dirt, which was a crossover between the Colin McRaes that had come before and what you could do with the new hardware, like the new 3D menus.

Race Driver: Grid (PC, PS3, Xbox 360, Codemasters, 2008)

During Grid's development, we were getting more from the engine – the PhyreEngine, as it was then, which became Ego. It felt like we were rocking it. It felt like we were travelling on a train at 200mph, laying the track in front of us as we went. We just knew how to build driving games quickly, with few mistakes, but also to innovate as we went. I wanted Grid to have a structure that other driving games still didn't. Gran Turismo didn't and Forza Motorsport didn't – you just did one set of races, did another set of races, on and on until you got bored and then you walked away. I wanted to have a start and an end with real chapter points as you went through.

We had the first hour or so of the game mapped out [and decided] when you unlocked a lot of things that you could do. Basically, we took those elements and just stretched them out over the span of the game, and that made a big difference. It meant that when you did unlock the ability to hire drivers, it was a real moment.

There were other elements, riffing on what we knew worked. We had Rewind, which allowed you to look at damage and also correct mistakes. It was more forgiving. We had difficulty levels. Anyone could play the game quite easily, and they had choices. You could do whatever you wanted.

The whole game just seemed to come together with a sense of fun. We had fun making it and you can just hear it, even if you listen to the lady who's saying the names at the start of the game. I always call myself Spanky, just for fun, and you can hear when she says the word 'Spanky', she's got this little giggle, because she was having fun reading out the names. I think you can always tell when the developers have had fun making a game, and that was one where you could really tell we had fun.

Forza Horizon (Xbox 360, Playground Games, 2012)

Dirt 2 was where we probably had the most fun, because the tools and tech were just absolutely nailed. But, for me, it felt like the end of the journey. I was Codemasters through and through. I was its biggest supporter, but I felt, 'I can't take these games any further. I just don't know what I'll do with them. They're essentially still linear'. I played Test Drive Unlimited, which had a big influence on me. I played Midnight Club: LA, which had an influence as well. It was a masterpiece, and I thought, 'What do I really want to do?' Well, there were several things I wanted to do. I wanted to take Grid, probably roll it in with Dirt and make an open-world version of that game.

Right, OK, if I'm ever going to leave Codemasters, now's the time to do it.

Even though I really liked working on the first F1, setting the team up, it's not where I wanted to continue. I knew the first one would be fun. Did I want to work on a yearly iteration? No, I did not. I thought, 'Right, OK, if I'm ever going to leave Codemasters, now's the time to do it'. It was a really, really challenging time to set up a new team as well, because there was the 2008 crash, and a real push for mobile games – console was dead and mobile was taking over. So all the publishers were reining back. We found it quite hard to actually find a publishing deal.

We were about a week away from me having to say, 'Look, I'm out of money'. It was really, really tough. But we stayed with Xbox. We kept talking to them. What we didn't realise at the time was that we were one of 17 companies pitching for the second [Forza series, to go alongside Turn 10's]. When we got the deal, it was such a moment. I was in Pizza Express with my daughter at the time. I shouted so loud when I learned. Everyone in that restaurant was looking at me but it was a real moment, a real achievement.

Forza Horizon 4 (PC, Xbox One, Xbox Series, Playground Games, 2018)

The UK [providing the setting for Forza Horizon 4] was a surprise. We ran a process where we assess potential locations for things like biome diversity, opportunities for new racing, visual differences between the current and the previous game, and I think Australia was a surprise in Horizon 3 because you think there is not a lot of biome diversity: 'It's just another hot country'. But when you investigate it, it's so wonderfully diverse. You've got lagoons, you've got wonderful forests, deserts, mountains – you've got so much diversity there, so it works. In the UK, you think the same: 'What's in the UK? What's there? It's just a few rolling hills'. Then you investigate and you find, actually, no, there's a lot going on here. So it appeared at the top of our list. It was right for Horizon 4.

Everything else [in Horizon 4] is about constant iteration. Games are not the one or two big decisions you make at the start of development. They are the hundreds of thousands of small decisions, each one trying to make the game better in a little way. All these things add up to the whole. And that's what we always tried to do: 'How do you make the lighting better? How do you make the skies better?' It was just constant push, push, push.

As studio head and game director, from a development point of view, my role was pretty much the same. I got involved in the areas I like to get involved in or where I thought I could add value. I bolstered the production team so I didn't have to worry so much about product delivery – I could focus more on the art and the tech and the design. But, from a business perspective, when you're running your own company, that takes up a large amount of mind share.

Forza Horizon 5 (PC, PS5, Xbox One, Xbox Series, Playground Games, 2021)

As developers, you think you need to make changes. But you have to be very careful that you're not making changes for the sake of it. If there's an audience there who really love the game, you have to tread very carefully. But we did iterate throughout the series, led by what we knew our audience liked doing. Forza Horizon 4 was [the moment when] the series was really taking off. We were mid-development on Forza Horizon 5 by then, but yeah, you felt a little bit of pressure – don't rock the boat.

This was during COVID, which just changed everything for us as a team. We really needed to be together to do our best work, and we were working from home for a large portion of development, and that impacted us. I had to take a lot of my key creative and technical leads and move them over to Fable, partly because of COVID, but also I found that you just can't split the mind share between two titles and do a great job in both.

That meant I had to promote a lot of junior staff in the Forza Horizon team into quite senior positions. That meant I had to focus all my time on Forza Horizon away from Fable, which is where I wanted to spend some time. This all meant that the risk-taking was a little bit lower than we would have liked because we just couldn't afford to take it on, not through COVID, and not with a younger team. But we're proud of the game we delivered. I think it is a great game, but for me, Forza Horizon 4 was my favourite game. It felt like my Dirt 2 moment. That was the game that I really enjoyed, where I thought everything came together. I love the subtle lighting that you get in the UK setting – it was brilliant. I'm very proud of Forza Horizon 5, but that was definitely the last Forza Horizon I had in me.

Unannounced Lighthouse Games Project (Platforms and release date TBC)

I missed that blue sky, as I had with Dirt 2. There was a game I would have liked to have built that I couldn't at Codemasters. That's what seeded Playground. And again, there was a game that I wanted to build at Playground, a driving game, that I could not make. I couldn't transform Forza Horizon into it for many reasons, and shouldn't have done so. It was a different driving game.

I thought, 'Right, well, if I'm going to leave, I've got two choices: I can either retire, or I can go again'. And I left. I spent two months thinking about this, and it was itching away at me. I thought, 'No, I've got to go and build this. I've got to build this game'. That was the seed. I've been very, very lucky that I've managed to hire a lot of great people from Codemasters. Some people who didn't join me back in the day, who felt they missed out, they've joined me now, but also a lot of people from Playground Games who've come to join me on this journey. It is genuinely the best team I could ever have hoped to have assembled. I'm really pleased with that.

Check out the best racing games for more quick escapes!

Phil Iwaniuk is a multi-faceted journalist, video producer, presenter, and reviewer. Specialising in PC hardware and gaming, he's written for publications including PCGamesN, PC Gamer, GamesRadar, The Guardian, Tom's Hardware, TechRadar, Eurogamer, Trusted Reviews, VG247, Yallo, IGN, and Rolling Stone, among others.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.