Yes, we Cannes

For all the glitz and glamour of Cannes, a fest where attendees are treated to champagne parties and scarily pricy hors-d'oeuvres, the single object on everyones wish list is a shiny Palme dOr. The 24-carat trophy, awarded each year to the best film in competition, is one of the mediums most prestigious accolades. The judges are also pretty starry; this years jury includes the Coens, Xavier Dolan and Guillermo del Toro. Cannes may be famous for audiences who proudly boo at screenings, but its also a place that recognises or at least sparks debate on the accomplishments of world cinema. And by tracking each Palme dOr winner, you can follow the development of film since 1954. The prize has gone to arthouse landmarks like Taste Of Cherry and Rosetta, but also to mainstream fare such as Pulp Fiction and Apocalypse Now. (And If you didnt pay attention at school, Palme dOr is French for Golden Palm.)

1955: Marty (Delbert Mann)

Although the festival launched in 1946, the first Palme dOr wasnt awarded until 1955. That honour fell to Marty, an American romantic drama with Ernest Borgnine as a 34-year-old bachelor butcher pressured by his family into finding a wife. The sentimental crowdpleaser isnt a typical auteuristic Cannes winner, and to this date is the only Palme dOr winner to also bag a Best Picture Oscar.

1956: Le Monde Du Silence (Jacques-Yves Cousteau, Louis Malle)

One of only two docs so far to win the Palme dOr, Cousteau and Malles dazzling sunken adventure took viewers across the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea, amongst its many watery delights. The French duo dived below the surface into a deep blue world full of sharks and whales, and shot with what was then an innovative form of ocean cinematography. It heavily influenced Wes Anderson for The Life Aquatic, and is at the very least more educational than a typical afternoon watching yachts depart Canness beaches.

1957: Friendly Persuasion (William Wyler)

It will pleasure you in a hundred ways! said the films tagline, not really indicating it was for a period drama about a family of Quakers caught up in the American Civil War. Jess and Eliza Birdwell, played by Gary Cooper and Dorothy McGuire, wish to run a staunchly anti-violence household, but are forced to reconsider their pacifism when caught in the wrong place at wrong time Indiana in 1862.

1958: The Cranes Are Flying (Mikhail Kalatozov)

Kalatozovs black-and-white Soviet drama details the hardship of World War 2 upon a young couple, Veronika and Boris, who separate when the latter is drafted. When Boris dies in action, Veronika is none the wiser, but is already a victim of her own growing stack of personal tragedies. The film is still admired to this day for its focus on the more human aspects of war and the longstanding effects upon its sufferers.

1959: Black Orpheus (Marcel Camus)

Adapted from a Brazilian play, Black Orpheus took the stories of Eurydice and Orpheus from classic Greek mythology, and relocated them to a 20th Century favela during Carnival. Marcel Camus (no relation to Albert) added samba beats and a bossa nova score for a cultural talking point Barack Obamas memoir mentions nearly leaving the cinema mid-film when suspecting his mother admired its depiction of black children as simple fantasies that had been forbidden to a white, middle-class girl from Kansas.

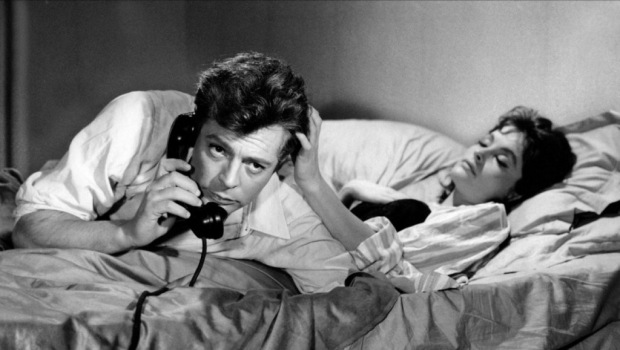

1960: La Dolce Vita (Federico Fellini)

The term Felliniesque obviously wouldnt exist without Fellini, but it was with La Dolce Vita (the good life) that he introduced the word paparazzi stemming from an invasive journalist called Paparazzo. However, told in seven chapters, the film belongs to Marcello Mastroianni, who spends an existential week in Rome going through the motions: he swings like a stylish metronome between wild parties and extreme loneliness, while making a living by chasing news stories around the European city. Who knows why Cannes audiences identified with it...

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

1961: The Long Absence (Henri Colpi), Viridiana (Luis Buuel)

A year after the Vatican condemned La Dolce Vita, the same treatment awaited Viridiana for its story of a nun reconsidering her Catholic vows the reason being a visit to her uncle that ends us becoming not quite a routine catch-up. Sharing the prize (and less of the controversy) was Colpis The Long Absence, a simpler drama about a woman who rediscovers her long-lost husband after a 16-year disappearance. Just one problem: he has amnesia.

1962: Keeper Of Promises (Anselmo Duarte)

The main character of Keeper Of Promises (also known as The Given Word) may be best friends with a donkey, but similarities with Shrek end there. Instead, Duartes fable concerns a poverty-stricken man who prays for his dying donkey to recover; in return, he promises to carry a large cross to a church in Salvador. When the donkey survives, will the man stick to his word? (The titles a bit of a giveaway here.)

1963: The Leopard (Luchino Visconti)

The 195-minute version of The Leopard that played Cannes was, believe it or not, edited down from a longer cut. Its not that surprising considering its a weighty crime period drama about a Sicilian family attempting to maintain its aristocratic lifestyle. Furthermore, the grand nature is part of the appeal, and was named by Martin Scorsese as a major influence.