I might die exploring Elite: Dangerous, and I'm totally OK with that

I am a total sucker for game maps. I like to peer at them, spool around them, afford them the furrow-browed curiosity most people reserve for pre-release GTA screenshots, or barely legible food use-by dates, or the first genitals you’ve ever seen up close. More than anything else, I love filling them in, most often ignoring the main thrust of a game to do so. I’ll head to every far-flung corner just to see the feathered edges of an unfilled chart disappear, replaced by solid, pleasing topographical detail.

I’m not entirely sure why.

- Vote for Elite: Dangeous in the Best Xbox One Game category at the upcoming Golden Joystick Awards 2016 and claim three games for $1 / £1 for taking part.

It’s not because I want to find every Easter Egg, or every lazily hidden artefact – that’s a twinkling by-product of my virtual hobby, but I’m not much of a looter – nor is it a desperate need for completion (the last game I 100%-ed was quite probably Dynasty Warriors 3).

It might be ownership, that creakingly colonial view that if there is a blank space on a map, it ought to be coloured-in in one’s own country’s colours. It might be a babyish pleasure at the simplest of the medium’s interactions – I went here, and the invisible cartographer that follows me around in most of my games means I can prove it. I’m not even sure it matters – I just love it.

It turns out, game designers must feel the same way as me – there’s never been a better time for mapping in games. Dragon Age: Inquisition contains beautifully scrawled, ink-stained jobs for sub-areas, couched within grand (and often indecipherable) maps for every one of its hubs, themselves couched within a gigantic global view. None-more-hardcore JRPG series Etrian Odyssey has you drawing your own maps, meaning it’s entirely your fault if you accidentally mistake the icon for “door” with the one for “furious bear”. Hell, Ubisoft has made revealing chunks of charts a central mechanic across all of its AAA games.

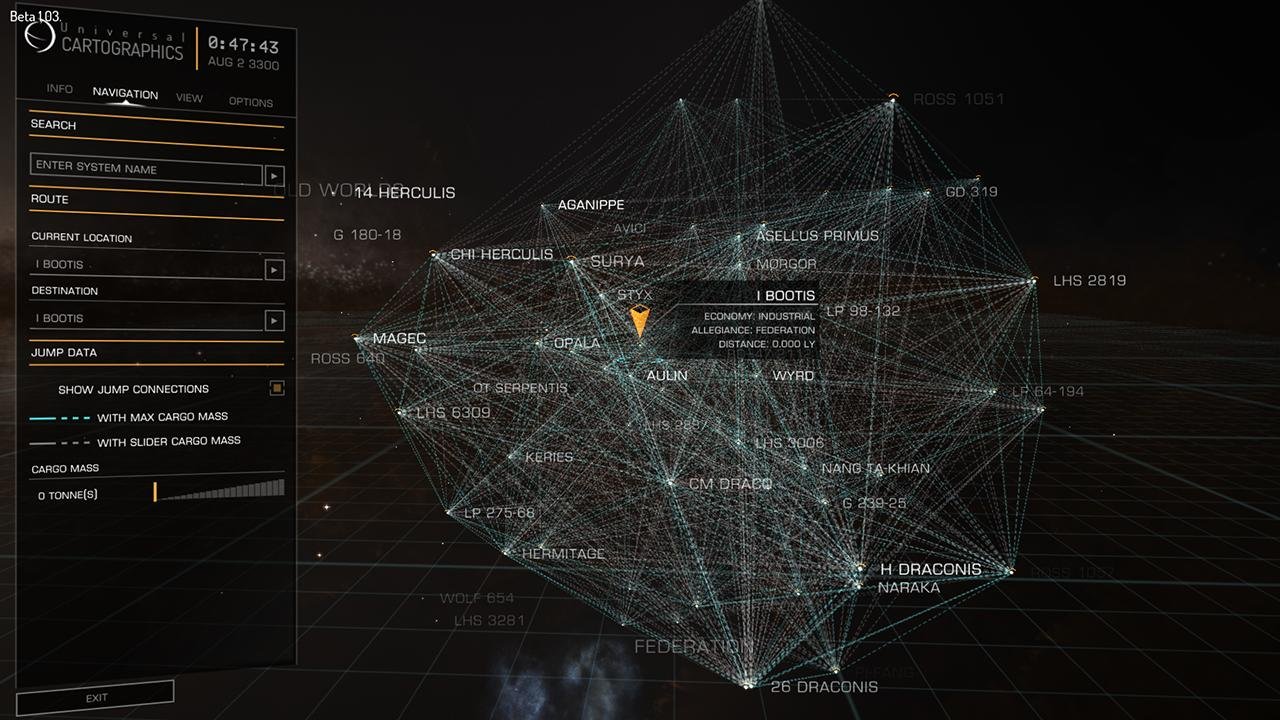

And then there’s upcoming Xbox One (and already-released PC) prospect, Elite: Dangerous, which presents me with something altogether newer, and amazingly exciting. But I’ll get to that in a bit.

Let's talk about a weird, achingly pretentious philosophical field called Psychogeography. At its simplest level (and, believe me, it gets horrifyingly complex), it attempts to connect human experience with the landscape around you, both natural and man-made. Being surrounded by tall buildings can make you feel small; standing atop a hill can make you feel invigorated, even powerful.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

And it cuts both ways - unassuming places become important because of what you experience in and around them. For instance, I once had a catastrophic date in a Cineworld in Islington, the long (and, I’ll admit, slightly drunken) walk and slight upward incline coming from Kings Cross Station contributing to me falling asleep during the crap second act of Maleficent.

For most, this is a place where you go to watch John Wick and eat nachos. For me, it comes loaded with phantom cringing and an odd thankfulness that my total failure to impress a girl meant I ended up with someone far cooler (and more willing/able to cope with me snoring in public places).

It’s easy to see how Psychogeography applies to game design – Skyrim’s wide-open spaces make you keen to explore even its most barren Nordic stretches, where Dishonored’s cramped streets give you a sense of being trapped even before you’re being hunted by men on enormous metal grasshopper leg-mechs. Similarly, a single dead tree in Red Dead Redemption can become the source of a memory about one of its ambient events – saving a hanging man silhouetted by sunset or some such dusty reverie.

But there’s little natural about this. Design is just that – designed. Someone wanted you to feel these things about a game’s landscape, and even when you’re imprinting your own memories on an in-game location, it’s almost always because of a confluence of systems, all put there to allow for just such an occasion where an eagle attacks a man who steps on a honey badger and then falls off a cliff.

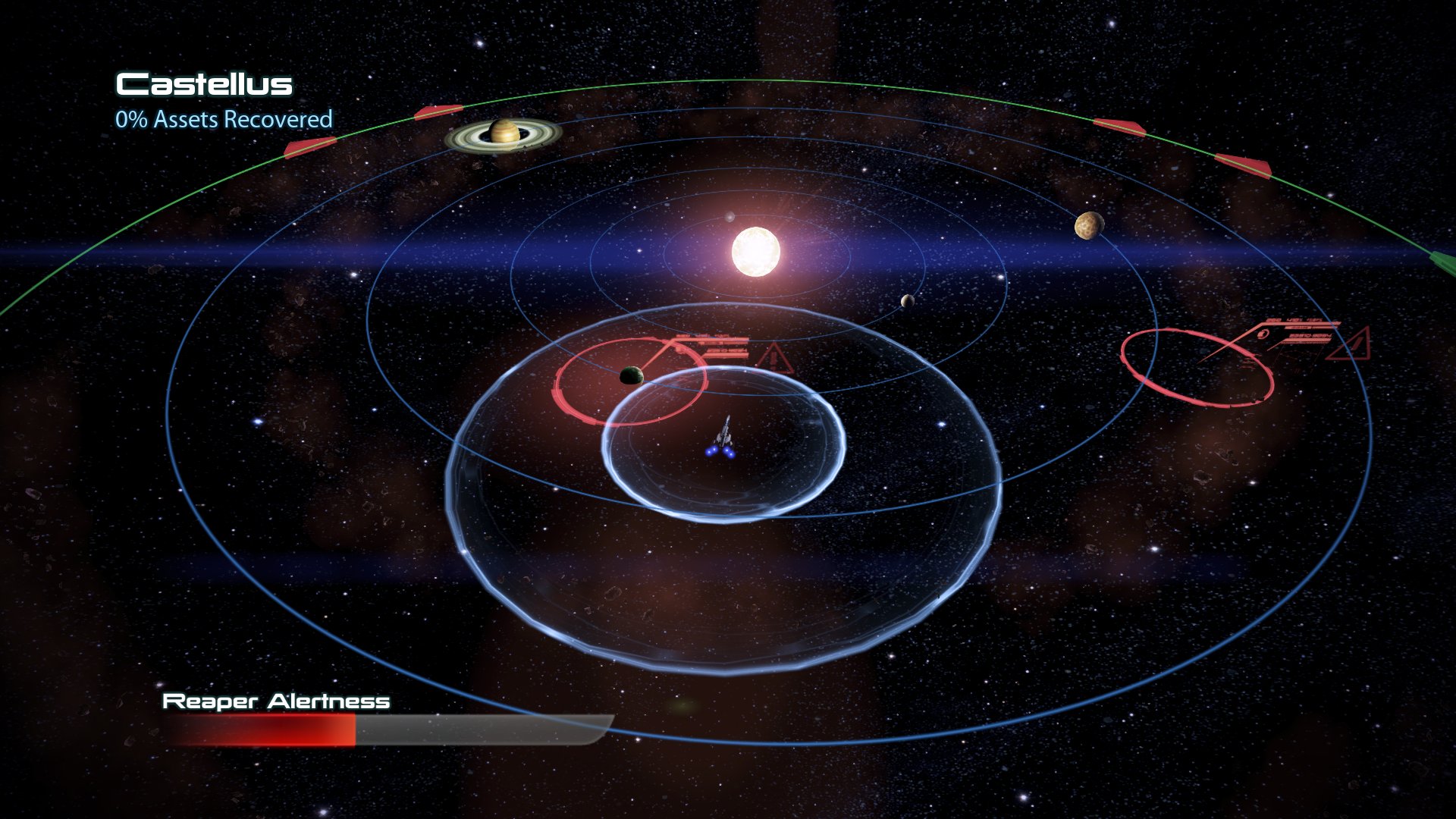

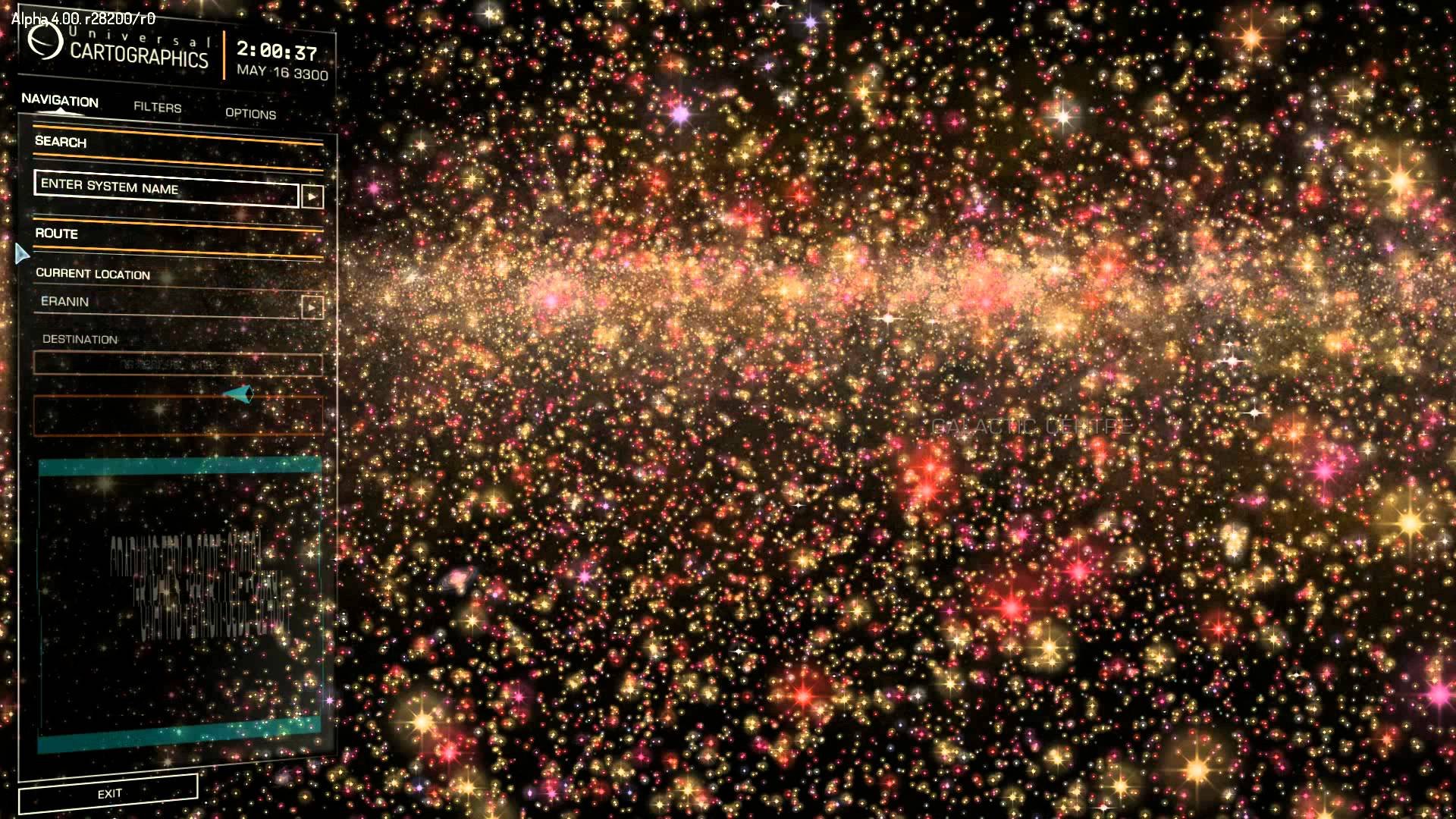

Elite: Dangerous is different. It’s offering something almost entirely new, particularly on console. It’s bordering on a truly natural world, inside a game. At its literal core, it’s a real-life star chart, a painstaking recreation of the 140,000-odd solar systems we’ve discovered as a species. That leaves, oh, about 399,999,860,000 other systems that have been procedurally generated, spun into digital existence through a cocktail of real-life physics, astronomical data and good old-fashioned random number generators.

The landscape of Elite’s galaxy has appeared in about as natural a way as games can manage. Which means when it makes you feel something – awe at a twin-sun system, or even humdrum boredom at another gas giant - you’re not being manipulated by it, you’re reacting in the same way you would to, say, a tree shaped like a penis (which is to say, most trees – I find trees hilarious).

On the flipside, it means that that sense of ownership, that you’re imprinting something on the world by simply being there, is more truthful than ever before. The opportunity for traditionally game-y ambient fun is there – manipulating a galactic economy using the game’s trading systems is possible, as is the ability to target, track and hunt down another player with a bounty on their head across the entirety of the Milky Way – but to me the most exciting system here is the simplest. Mapping.

Pare down your ship to its most basic parts, install a powerful engine, stock up on fuel and go somewhere literally no one has been before. Not a player, not a designer, no one. If you’re the first to discover a system, it’s yours – right down to having your name bolted onto the end of its title, proudly displayed to every other player in the game.

It’s the greatest map in gaming’s history, the opportunity for dorks like me to feel like they’re actually making a mark, a race for the stars that can feel personal and universal all at once. Best of all, I’ll never be able to finish this map – no one will – meaning that simple pleasure of finding a place, proving it’s there, never needs to stop.

Oh god. I’m probably going to die playing this thing.