Tom King looks back on Mister Miracle: "What gets us through is just getting through"

Tom King looks back on the brilliant 12-issue series Mister Miracle

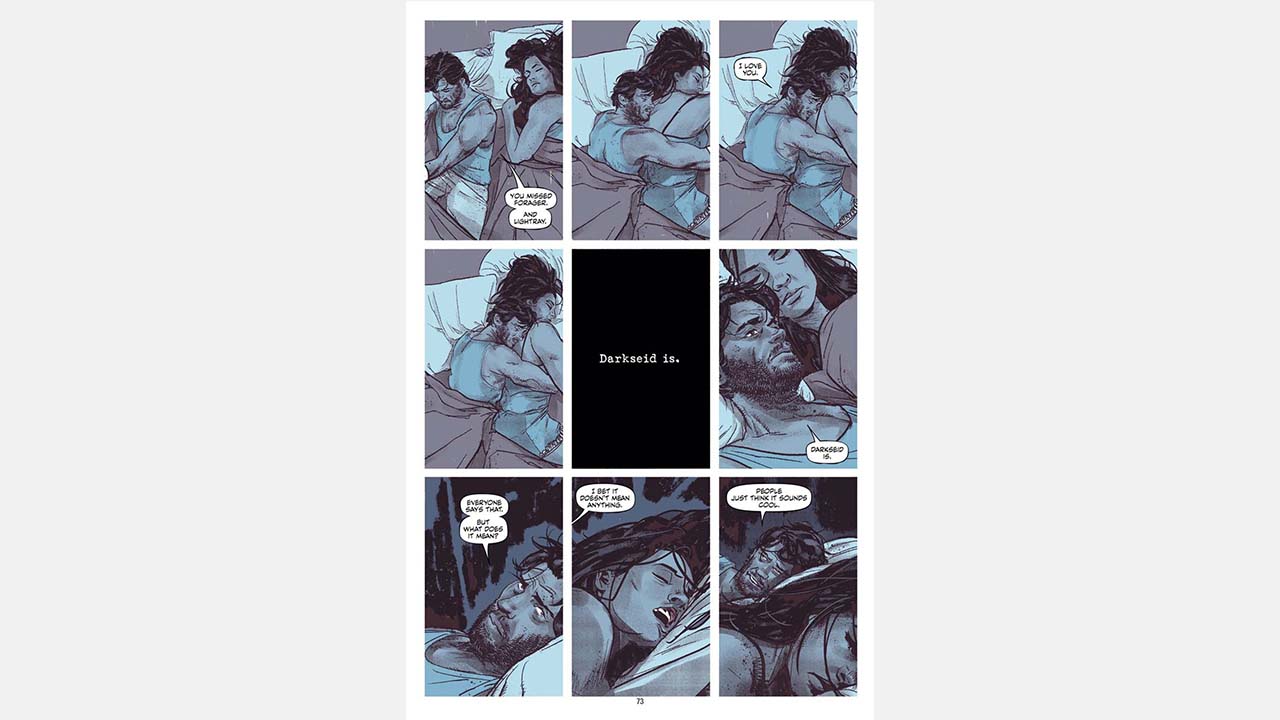

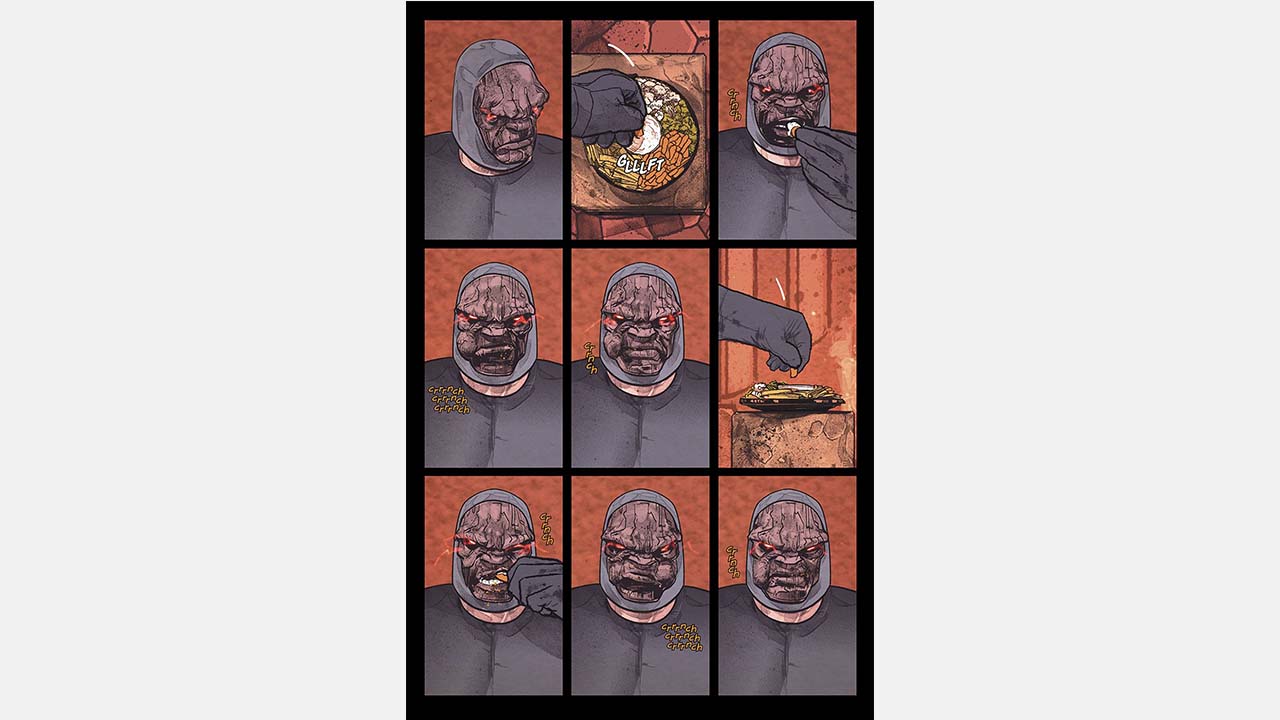

"Darkseid is."

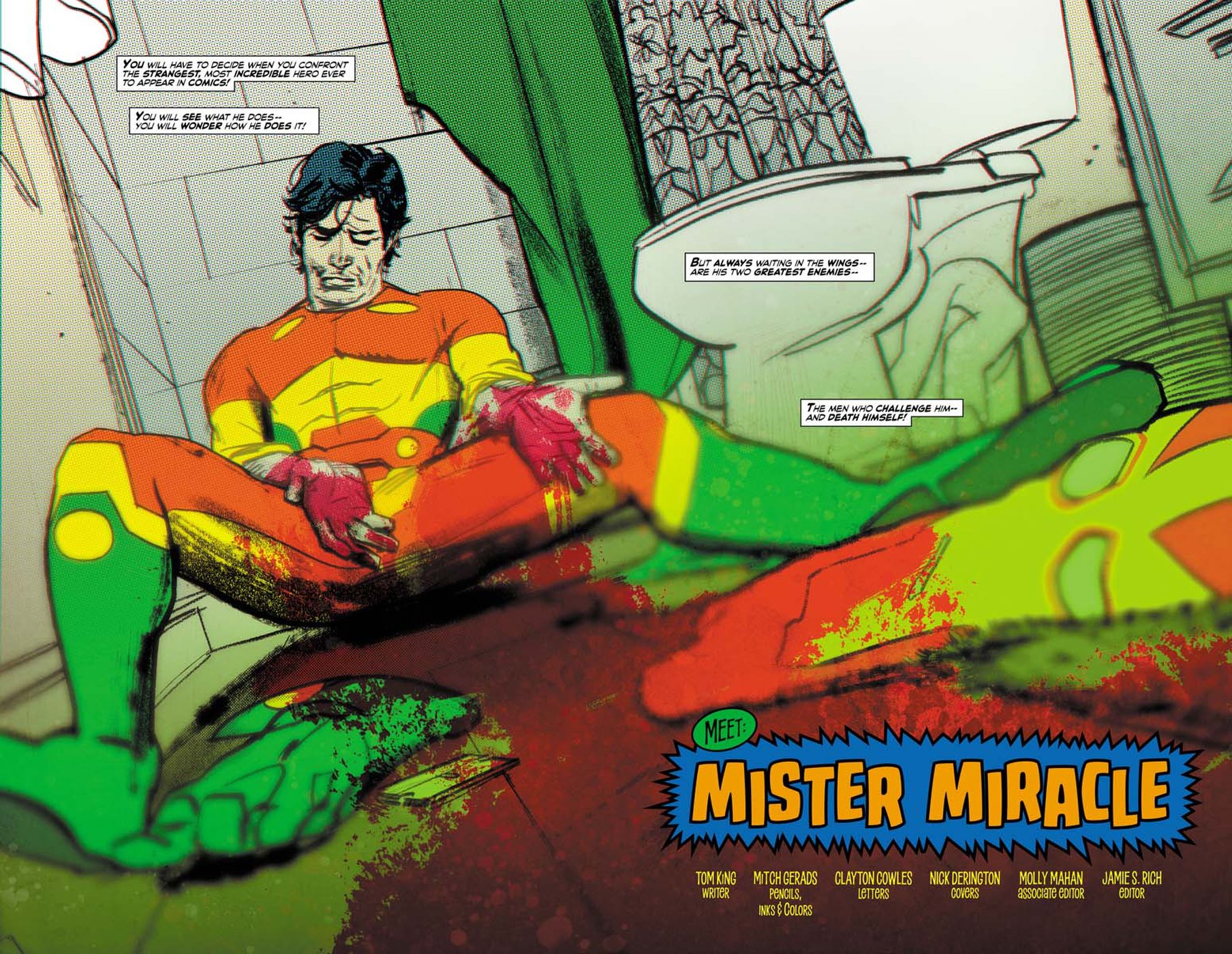

These two words, uttered throughout DC comics book in reference to the heroes’ biggest bad, never seemed more unsettling than in the recent 12-issue series Mister Miracle. Constantly interrupting the narrative of the story, they became a chilling metaphor for mental illness, the pressures of daily life, and the constant temptation to give up.

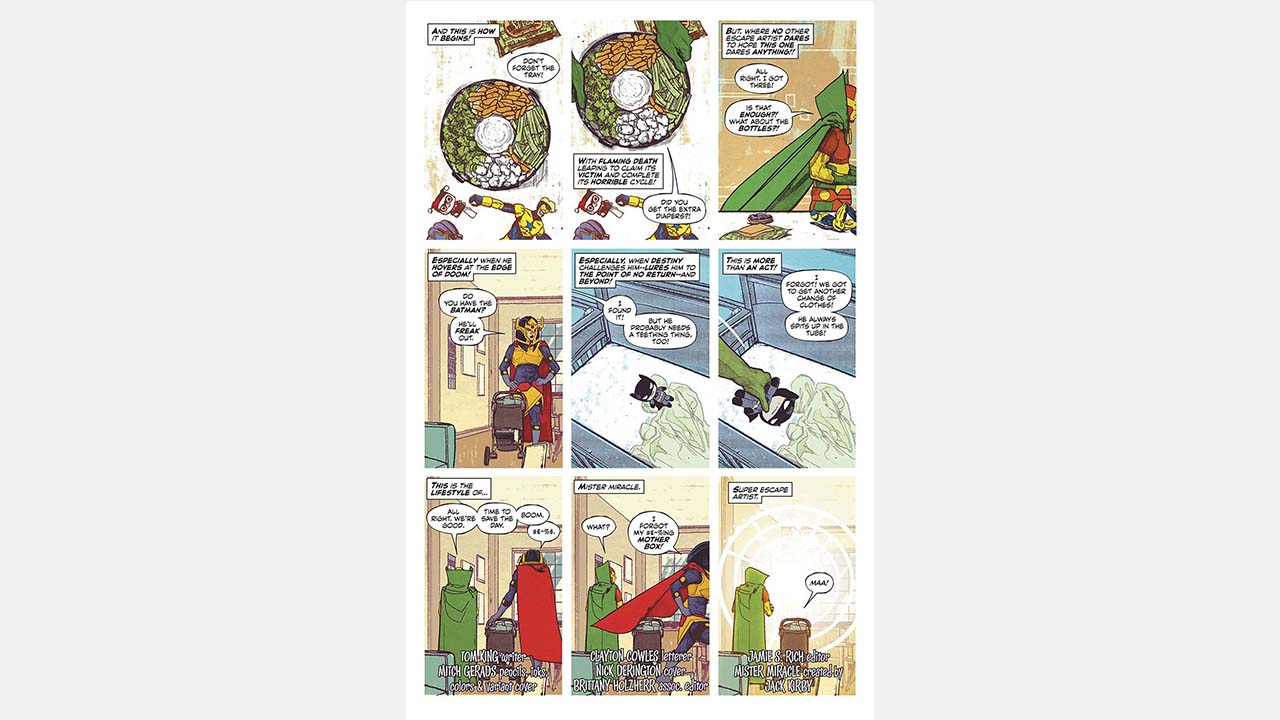

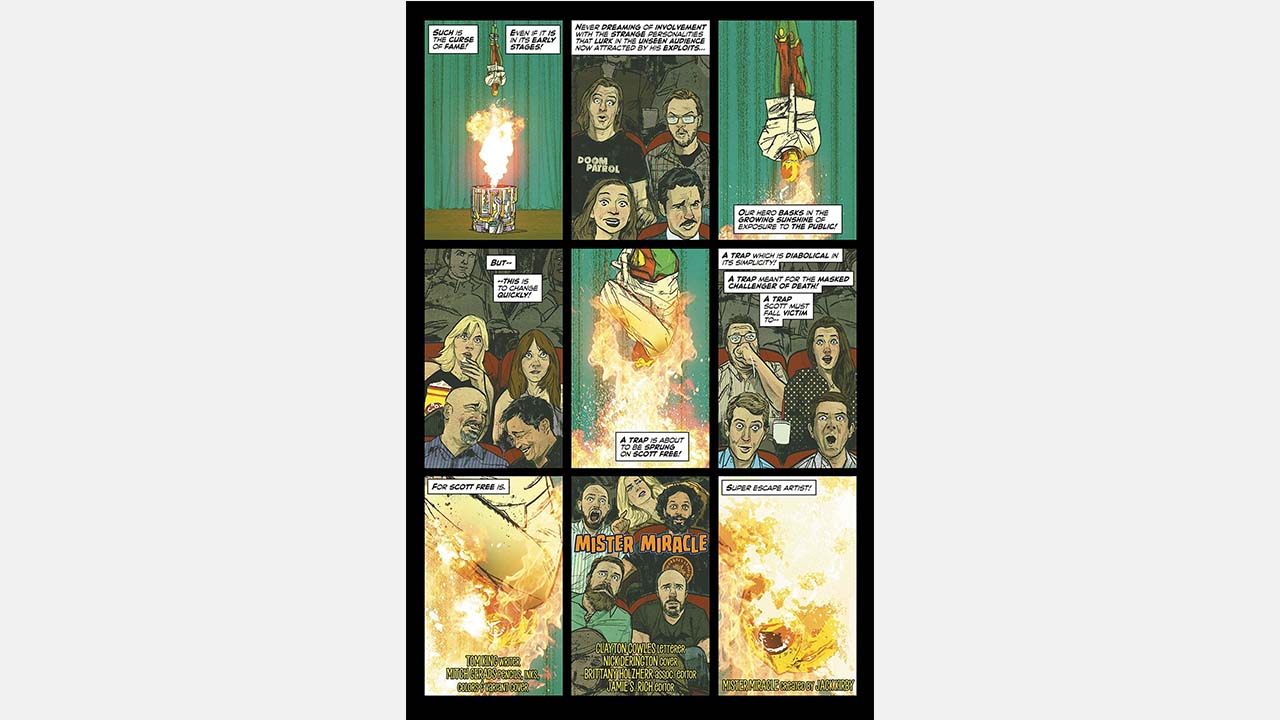

Picking up from the storyline in the original 1970s series by Jack Kirby, Mister Miracle took the character of Scott Free - son of Highfather of New Genesis, traded to Darkseid for an end to war, escaped to Earth and became a crime-fighting escape artist married to fellow refugee Big Barda - and grounded him in a world that was equal parts realistic and unreal. In the aftermath of a suicide attempt to “escape life,” Scott found himself wondering if he could trust his own senses - or was even still alive - as the war against Darkseid escalated, the traumas of the past weighed on him, and the only way to end the bloodshed seemed to be to repeat the tragedies of the past.

Also, there were veggie plates.

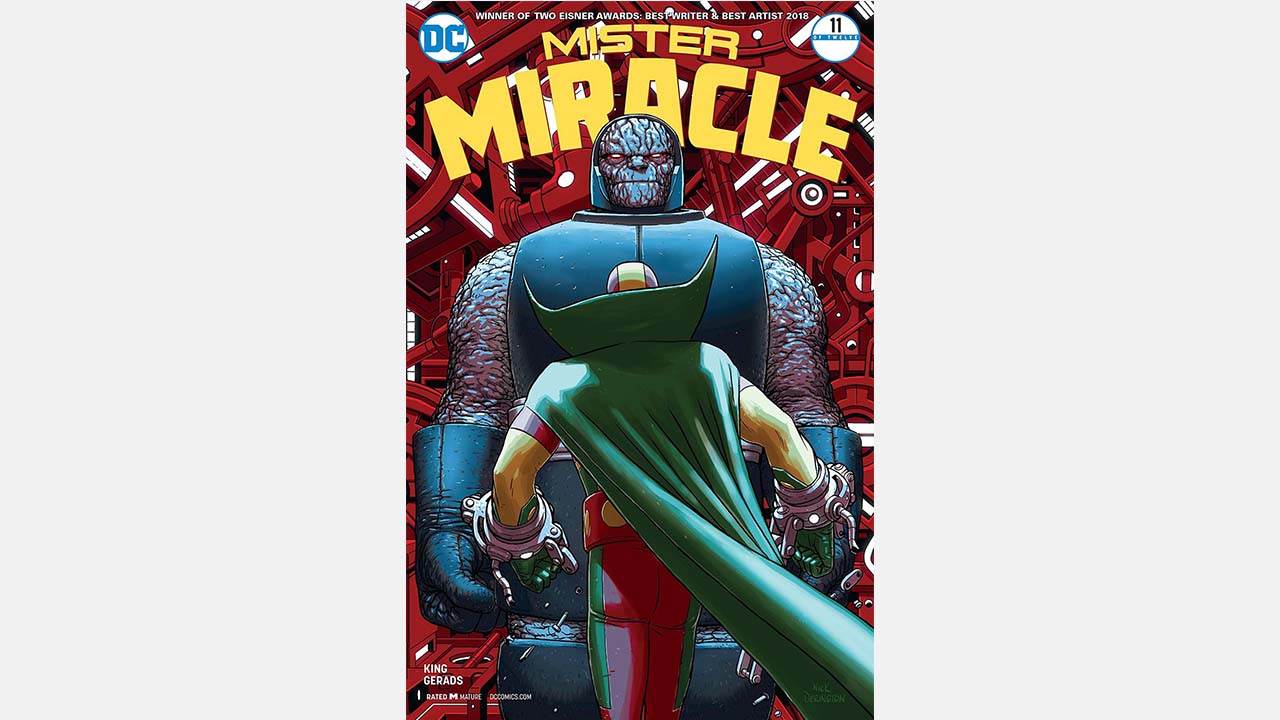

Mister Miracle proved an unexpected hit for DC, winning two Eisner awards and going through multiple reprints as the series moved toward its surreal, moving conclusion. With the collection of the series hitting stores this week, Newsarama spoke with series writer Tom King, who reteamed with his The Sheriff of Babylon artist Mitch Gerads for the book, on the phone for a look back.

Newsarama: Tom, what were some of the origins of the Mister Miracle title? What kind of setup or logline did you use to pitch your take on the character?

Tom King: I think the beginning idea was, and it evolved from there, was, “Here’s a guy who can escape anything, and so he says, ‘I can escape any challenge you can throw at me,’ so he decides to escape life, and he kills himself. And then the book goes on from there.”

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

Obviously, it evolved a lot, and became something a lot more personal, and political.

Nrama: What were some elements from the original Jack Kirby series that were most important to you, and how did you want to depict those elements? While it’s from a different perspective, they’re still very present in your version.

King: Yeah, absolutely. The whole idea was that no one can Out-Kirby Kirby - if you try to make it more cosmic and more epic, you’re going to fail. You can’t play any louder than Kirby is playing, so instead, we’re going to try to harmonize - play different notes, and try to fit them in with his notes.

So, the way to do that was to take Kirby’s ideas - which are these huge ideas that affect mankind and the world - and try to internalize them and turn them into sort of a metaphor for one family’s struggle to just through this world. Which I think is something that Kirby himself originated, and I’m just kind of standing on his shoulders and shouting a bit.

Nrama: There’s a lot of intimacy in his work that’s often overlooked because of the cosmic elements – the Fantastic Four stories really brought soap opera interaction to comics, and there are many moments of introspection in the original Fourth World books.

King: Oh yeah. When I read the Fourth World stuff, to me it reads like an incredibly personal work. It reads to me as a guy who’d been through war and come back from it; it reads to me as a guy who’d achieved his greatest dream in life, which was to become this sort of comic creator for his family and then lost it, and was trying to recover it when he moved from Marvel to DC. It’s known that he originally developed the Fourth World for Marvel as this kind of Asgardian world, then he brought it over to DC when he felt disrespected how Marvel treated him.

To me, when I read it, I see all of that mixed up - all that anger at Stan Lee, Marvel, all of that combined with a guy who grew up in the Jewish ghettos of the Lower East Side and had to scrap for everything he ever had, and fought his way through World War II – to me, it reads as an entirely personal work.

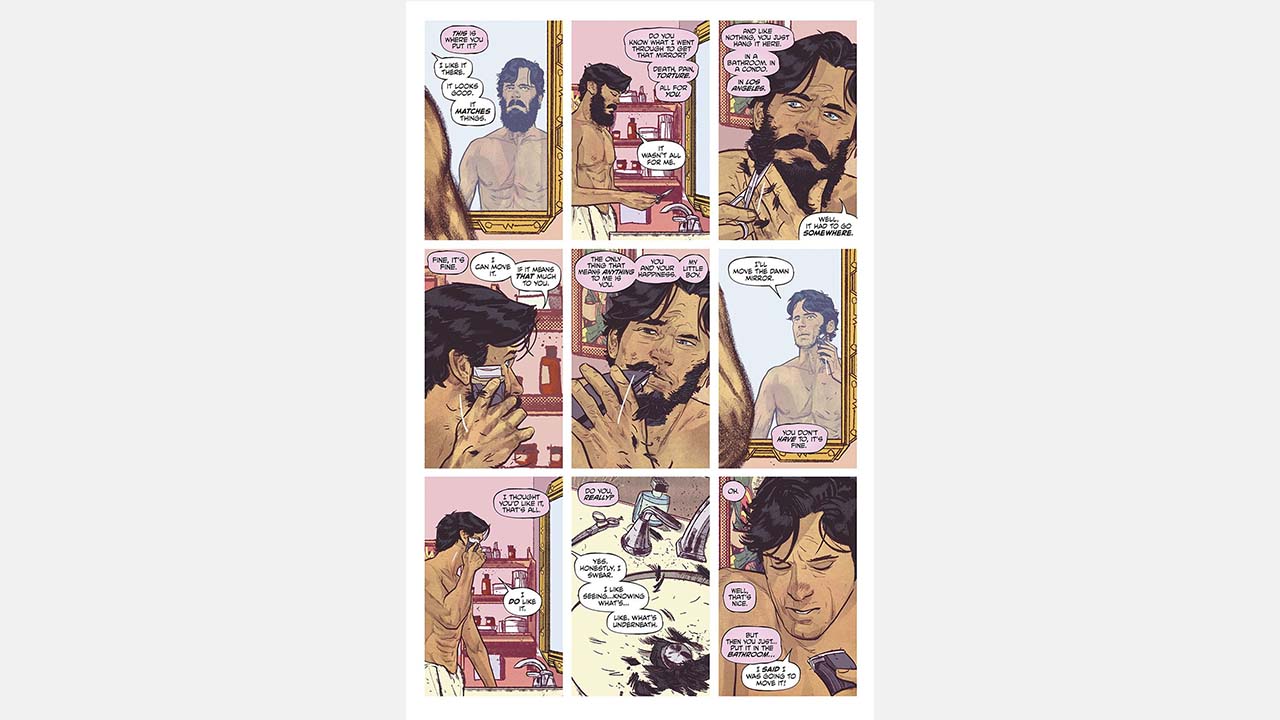

Most of all, of course, there’s the treatment of Big Barda, who’s clearly based on his wife Roz Kirby, and their relationship.

Nrama: There’s also an undercurrent of religion and religious dogma as part of that work, and that’s something I’ve seen in Mister Miracle and other things you’ve written – The Sheriff of Babylon, the use of William James and the alien religions in The Omega Men, for example. How did you interpret the use of religion and of the New Gods as capital-G Gods in this particular work?

King: Yeah, I think that’s a central factor of both the original work and my work – Mister Miracle himself is this Christ-like figure, he’s literally the son of God --

Nrama: I noticed the structure of your story echoes some elements of The Last Temptation of Christ.

King: Yeah, that’s actually true. But of course, the son of God sacrifices himself for our sins, and Mister Miracle does that, but he didn’t do it by choice – his father chose it for him. The man who can only do good in this world decided to do a horrible, evil thing, to give his only son to a torturer.

And you have it so Scott is able to correct that sacrifice and escape and be reborn, but he still has to go on and live his life. And I find that fascinating, and in many ways that’s the center of the book.

Nrama: You also have this theme of family in it, and the concept of familial loyalty and abuse. There’s been a lot of focus, and rightly so, on the book’s themes of fatherhood and the fear of bringing children into the world, but the focus is very heavily on the aftermath of being an abused child, and a fear of being unable to properly give love and to protect a child as a result of what you’ve experienced yourself.

King: Yeah – I personally didn’t have the happiest childhood, and I think a lot of nerds like me, a lot of people who are attracted to this story, are products of a similar experience. I think comics reach out to a lot of people who’ve experienced alienation in their youth.

But then, I found myself raising children and having that experience – how do you both avoid what was done to you and give the next generation something a little better, but not deny who you are as a person, and deal with the temptations of (the experiences that) ground you?

The revelation of having children is that you start to understand your parents a little more, for better and for worse. So that stuff with the family, that’s very personal to me.

Nrama: When you and Mitch were working together to try and visually depict those thematic elements of depression, alienation, questioning reality, “Darkseid Is” – what was that creative process like?

King: Mitch is my favorite artist in comics, and the story is as much him as it is me. It’s no coincidence that Mitch had his first child in the middle of drawing this, and almost as soon as young West appeared, young Jacob appeared.

It’s hard not to embrace clichés when writers talk about their artists. For me, Mitch makes writing as easy as possible. I can close my eyes and see what he’ll draw, and then he’ll draw that but a little better, which is the best way to write. And he’s also one of my best friends, so it feels like we’re partners in an old TV cop show, like we got each other’s backs, things like that.

Nrama: King and Gerads, Wednesdays at 9.

King: [Laughs] Mitch is kind of a quiet innovator. He comes more from the Alex Toth school, as opposed to the Jack Kirby school, and he’s sort of quietly revolutionizing comics, finding new ways of moving comics forward, of making them more realistic without losing the cartooning of it. I think he’s tearing down barriers in the field right now.

Nrama: A lot of the book focuses on - very subversively, toward the end - the nature of continuity, the circular nature of comics history and the DC Universe in particular. It seems to be saying, “Whatever’s going to happen is going to happen, but we’re sticking with this version of the characters.” Again, I was curious about your thoughts on continuity and the difficulty of tying things into a larger continuity base, especially given what you’re doing right now with Heroes in Crisis – Mister Miracle is very consciously poking at that “everything is going to reset” or “everything is going to come around again” mentality.

King: Yeah, there’s a little post-modernity to the whole thing, but also in the service of the emotional stakes of the story. Alan Moore said it best, right? “This is an imaginary story, but then aren’t they all?”

Nrama: And “Nothing ever ends,” from Watchmen.

King: Exactly. The idea at the end, not to spoil too much for people who haven’t read it, is that he has to decide whether he’s in-continuity or not, and that’s dealing with whether he can accept his life or not, or whether there’s something better out there that’s more ideal, and the idea of what’s real and what’s not is metaphorically put into this idea of what’s continuity and what’s not.

And of course it kind of relates to the idea of how you and I relate to the real world - just looking at our own reality and going, “What’s real and what’s not? What fits into continuity?” I kind of feel like the last three years of American life don’t fit into continuity. [Laughs] Continuity is broken.

Nrama: Well, there was that Astro City story where the guy finds out the woman he’s been dreaming about is his wife who was never born because she was erased in the last time-bending crisis…

King: That’s the famous one, Issue #½. Beautiful story.

Nrama: But what you just said about reality reminds me of the perspective that series has, and what you do in Mister Miracle, which is to provide this kind of, “looking in through the keyhole” perspective on the Fourth World and the DC Universe itself. The other heroes are off doing their own things, and Scott and Barda have this whole crazy war, which is on a cosmic scale but mostly keeps finding its way into their living room.

King: Yeah, and at the end, Scott has to choose - to embrace this crazy life that he built, or go back to “reality.” The cliché answer and the cliché scene would be to choose reality, but I don’t think that’s what the book is about.

Nrama: And by the end, you explore the idea that family, that the challenges of everyday life, can be seen as both Heaven and Hell…

King: Well, I wouldn’t put it exactly that way, because my wife might… [Laughs]

It’s tough for me to talk about any of this stuff, because I know what the book means to me, and what I intended with it, and I could lay it all out on this 1:1 ratio.

But for me, the magic of the book, or what makes the book good if it is good, is that it interacts with the audience and that the audience is involved in it and becomes part of it, the way Mister Miracle sort of becomes part of his own reality. So, if I give you the 1:1 answers, I feel like I’m kind of robbing the audience of the experience…

Nrama: And I don’t want to do that, or try to pull those answers from you – but it’s an interesting thing, sometimes, not to necessarily answer a question but to raise it in the first place.

King: Oh, I don’t think you’re doing that! But my defenses go up whenever I talk about the book. [Laughs]

I don’t want to take those questions from the audience.

[Pause]

Wait, what was the question again?

Nrama: I didn’t quite get to it! [Laughs]

But you’re exploring these concepts of family and this very intimate perspective of a larger, chaotic universe where everything’s shifting around you constantly - where there’s war, there’s death, and you’re just trying to get though the challenge of being a person each day. And that seems to be the larger point of the book, that the real world can be as challenging as a fantastic one.

King: Absolutely. I think when comics work best, or at least they work best for me, it’s on two levels. One level is these big, bombastic awesome story that you’re kind of trapped inside of and can’t get out, and another level, you have that crazy story as a kind of analogy or metaphor for what happens in life.

So, when you read the original Galactus story by Kirby and Lee, you’re like, “Oh, this is a cool story, there’s this huge monster from space.” But then there’s also all this religious symbolism, and symbolism from the perspective of Silver Surfer, and you start to see what it’s like to have a mentor that’s not quite right and you have to rebel against him but you can’t. It works on all those levels.

We’re trying to do that with Mister Miracle. On the one level, it’s a story about a guy with a family who has to fight these huge demons and everything, but it’s also like what it’s like to just live with a family. Everyone I know lives in two worlds. There’s one world with their family trying to keep themselves together, and there’s the professional world, where they’re trying to build themselves into who they’ve always wanted to be. And sometimes, those two worlds clash.

Nrama: And I think that’s very similar to some of your other works, where you show these successful domestic partnerships – at least things where the concept of “It’s you and I against the world” makes more sense than, “Here are a lot of melodramatic obstacles coming between us.” You genuinely understand why Scott and Barda are together, and what bonds them.

King: Ah man, that’s true with Mister Miracle, but I’m also the guy who’s infamous for not letting Batman and Catwoman find their happy ending yet, so… [Laughs] I can’t say that I haven’t gone to the melodramatic pull-the-rug-out-from-under-you place yet in my work

Nrama: Well, that book’s less self-contained, so…

Any general thoughts about the response to the series and what it’s meant to you personally as we wrap up?

King: I started the series in a real bad place in my life. Not objectively; I was doing well, my family was happy and healthy, my job was going great, and it was my dream job. But somehow, there was something inside of me that was just driving me insane, and it had to do with my childhood, but also due to external events, what was going on with the country and the world.

And I wanted to write about that; I wanted to write about that contrast, about living in the moment right now. And when I look at the book, I think I did it. I’m insanely proud of it. I write a lot of stuff on a deadline; I write about a book a week, and sometimes I accomplish what I want, and sometimes I don’t. But with Mister Miracle, I’m really proud about how it came out. That’s all.

Nrama: Well, I hope you found some catharsis through doing this story.

King: [Laughs] I’m not sure if I believe in catharsis. If you read my work, it’s almost the opposite of catharsis! It’s like, catharsis isn’t what gets us through. What gets us through is just getting through. But I will say – I’ve gotten through.

Zack is a comics journalist, who has written primarily for Newsarama, GamesRadar, and Indy Week. His words have also appeared in The Washington Post, AXS, VOX, The Sports Network, Gambit, and more.