Inside the Image Comics - Marvel Comics break-up, according to Marvel's former top editor

Former Marvel editor-in-chief Tom DeFalco shared secrets about one of the comic book industry's most infamous exoduses

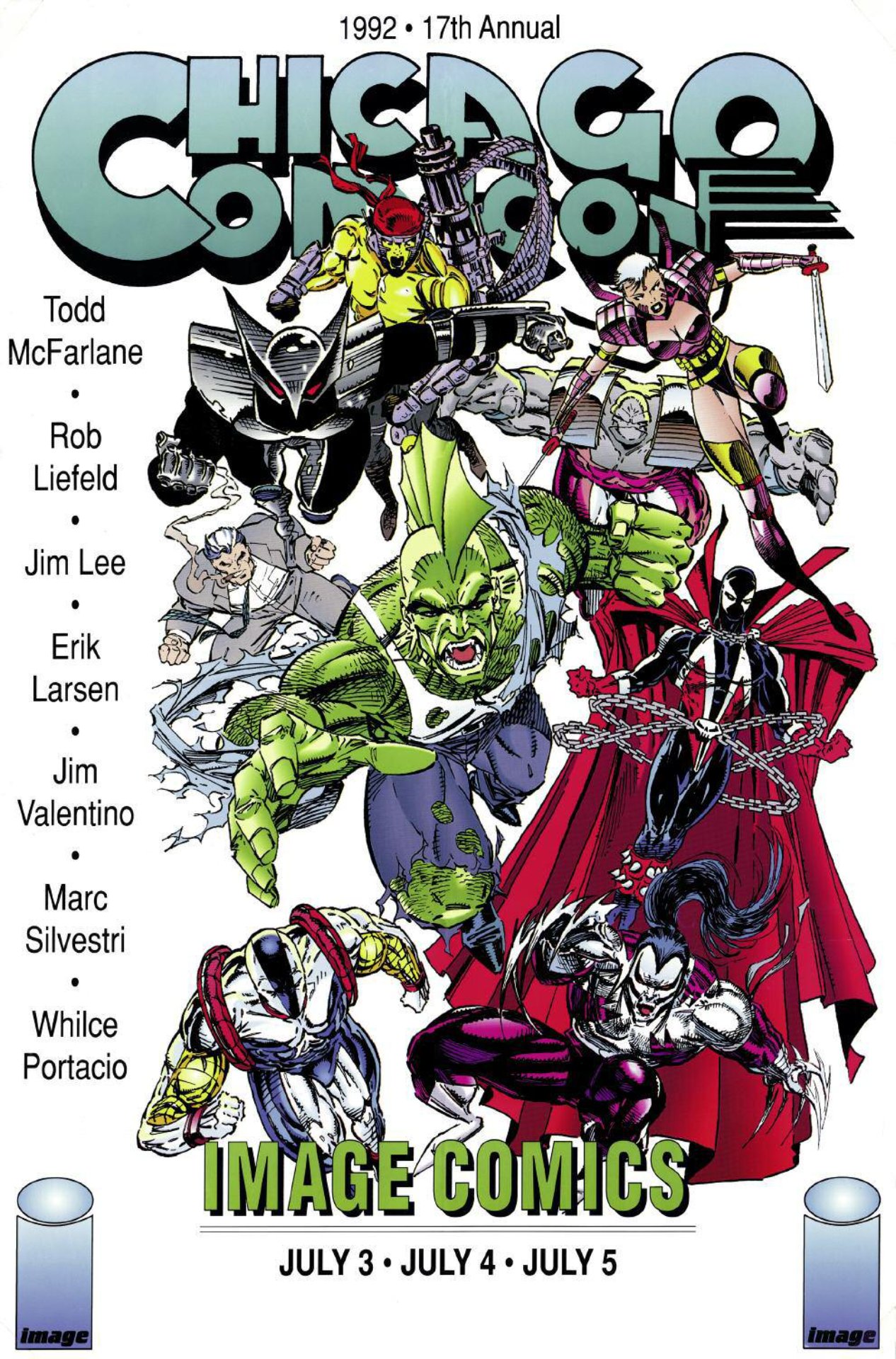

In 1992, seven comic book creators left behind what were very lucrative gigs at Marvel Comics and decided to strike out on their own. The move shocked the industry, but it resulted in the founding of Image Comics.

Taking its name from a 1989 Canon Rebel (that was camera without a phone) commercial starring tennis player Andre Agassi declaring "Image is everything," Image Comics has over three decades as of February 1 offered writers and artists complete ownership of their original properties.

In 2012 when the publisher was celebrating its 20th anniversary, Tom DeFalco, who was editor-in-chief at Marvel Comics in February 1992 remembered the events that led to the formation of Image. After all, he was in then-Marvel president Terry Stewart's office when Stewart met with Todd McFarlane, Jim Lee, and Rob Liefeld, three of the now-legendary group of seven freelance creators that includes Marc Silvestri, Erik Larsen, Jim Valentino, and Whilce Portacio - when Marvel first found out the group was severing ties with the publisher.

In an interview that took place in 2012, DeFalco told Newsarama he resents some of the things that happened in that infamous meeting, but not for things readers might necessarily expect. And as a comic creator himself, DeFalco understood the importance of what Image offered and still offers the comic industry.

Newsarama talked with DeFalco to get his personal side of the story, and to get his ideas on how Image Comics has affected creator rights. In this still relevant interview, DeFalco revealed the secret origin of Todd McFarlane's bestselling Spider-Man title (it wasn't created for McFarlane), reveals the now-infamous exit meeting was a PR stunt (at least according to DeFalco), and somewhat ironically gave his thoughts on the possible unionization of workers in the comic book industry.

Newsarama: Tom, what was the status of the comic book industry at the time, before the Image exodus happened, that not only set the stage for it but maybe even encouraged this kind of thing?

Tom DeFalco: Boy, that's a good question and I don't know if I can sum it all up in one answer.

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

Back when comics first started, a lot of creators had rights to the characters they created. Like Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster with Superman and Bob Kane with Batman. As years went on, other deals for those characters fell into place and other contracts were signed. And far be it from me to understand all these lawsuits over the Superman stuff.

But as time went on, the companies started to own everything.

Nrama: That was influenced somewhat by the Copyright Act of 1976, right?

DeFalco: Yeah, but it had been already starting in the '50s and the '60s, this whole idea of work-for-hire. The company started to approach these things as, you know, they owned it from the get-go. And by the time the '70s came around, that was the norm at the big companies.

Then underground comics started in the late '70s and into the '80s, and creators started to own the material that they were publishing. By the time the comic book Direct Market started to come about, there were established creators like Dave Sim with Cerebus, and Richard and Wendy Pini with ElfQuest. They would self-publish, and they basically owned everything.

As time went on, companies like Eclipse made deals with creators, where the creators would own it and they would publish it. As we got into the '80s, some of the independent publishers sold well, and some didn't. It all depended on the property.

There were other companies too, and I apologize to any of the key players I'm leaving out, but you get the gist of what I'm saying. The stage was being set, as you said, over time, for what we saw with Image. It was a long process, but that set the stage.

Nrama: What was the atmosphere at the major companies?

DeFalco: The major companies, and by that, I mean Marvel and DC, eventually started to react to these developments, and Marvel certainly took some steps in that regard with Epic Comics, which was an imprint Marvel had that, essentially, allowed creators to retain ownership of properties but gave Marvel the publishing rights.

Around the time of the Image guys, a couple of things happened. The first one was that Marvel was in the midst of a winning streak. We were getting a lot of publicity, and sales on a lot of our comics were moving forward and upward. And Marvel was actually paying creative incentives and royalties on the comics. So creators were actually making a decent living. More than a decent living.

I think around the time Marvel went public, the whole universe became aware of comics, and sales took another big leap. And suddenly, the Direct Market was on fire and sales were going up and everything was going terrific. And people started making real, serious money.

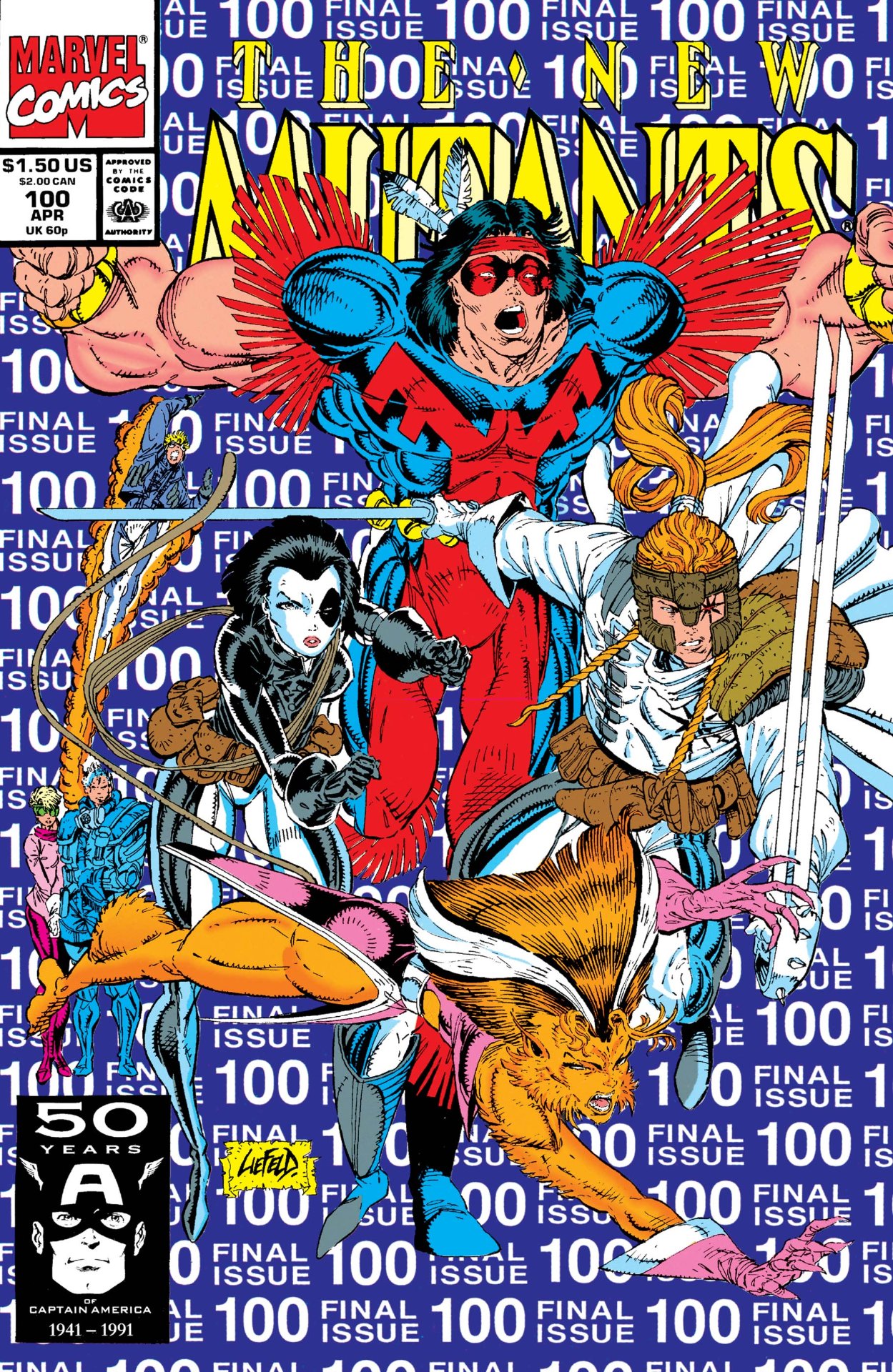

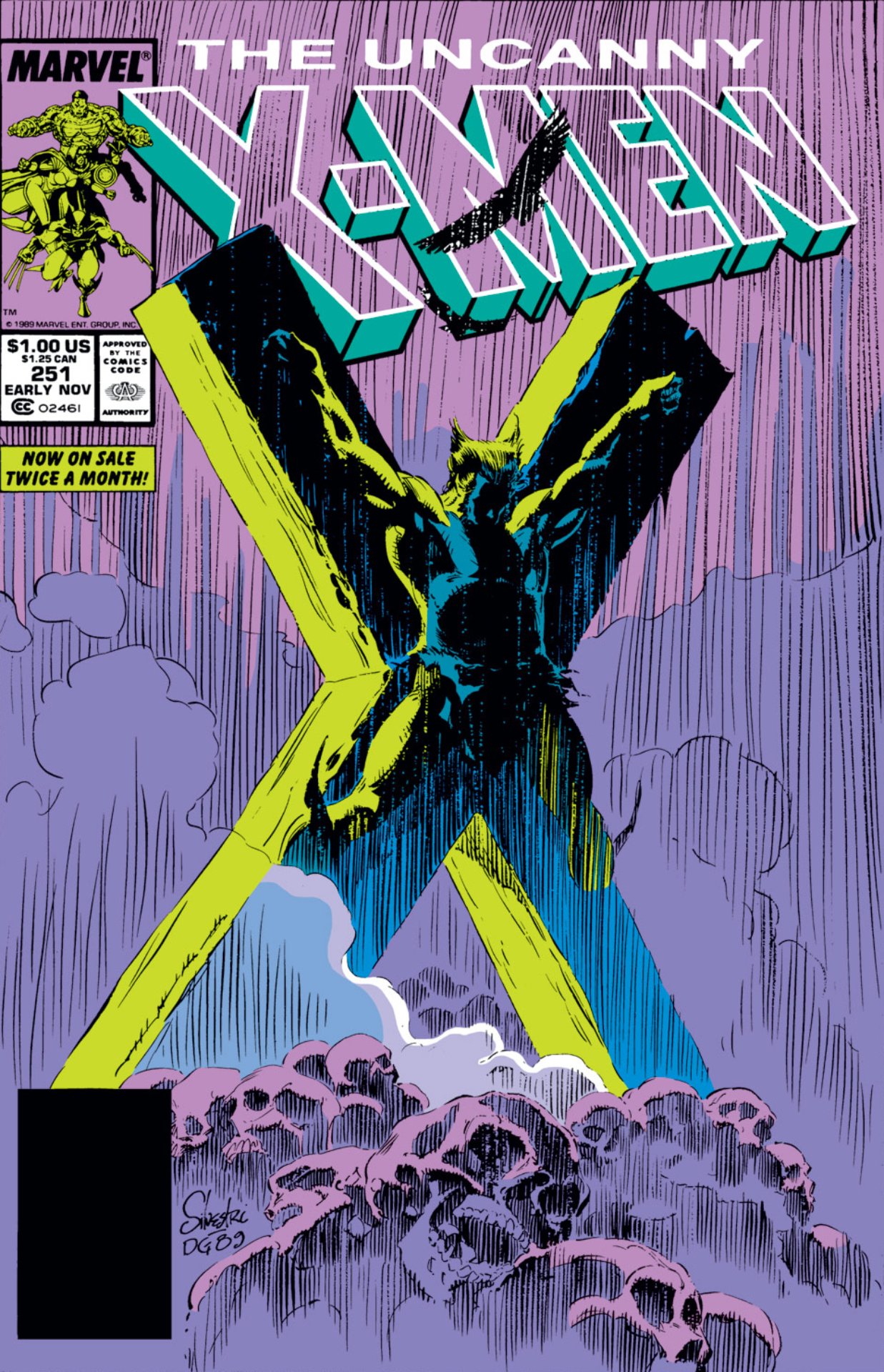

On the publishing end, to our own surprise, we started launching titles that were selling 500,000 copies, a million copies, three million copies — especially X-Men #1 and the Spider-Man title that Todd McFarlane did.

And I'll give you the true back-story of the Spider-Man title. I don't know how much of the truth is out there, but it might surprise you.

I was in Europe, I think at the London Book Fair, and I was talking to all our licensing people. And every one of our licensing people that was publishing Amazing Spider-Man complained that we were not publishing enough Spider-Man material for them. Every one of them.

And I sat down with our licensing person, and I did some quick math, and I realized, "Oh man! I could publish another Spider-Man title, and we'd make a profit even if we didn't publish it in America!"

So when I came back, I went to the editor of Spider-Man, Jim Salicrup, and I said, "Jim, you've got to publish another Spider-Man title."

And he said, "What are we going to call it?"

I said, "I don't know! Call it Spider-Man. I don't care what you call it. But you're going to publish another Spider-Man title."

And then later on, at some point, he came to me and said, "You know what? Todd McFarlane would like to try writing. What do you think if we let him write and draw it?"

I said, you know, "if you think he'll do a good job, go for it!"

I know people think we created the title for Todd, but he was kind of an afterthought.

Now he was a great afterthought. Because it was Todd, and Todd was really very hot at that particular time, I think the first issue of that Spider-Man title sold something like two million copies. I thought, "We didn't even have to sell a copy in America -- what a bonus!"

Those comic books made some very serious money. Very serious money.

I'm a student of history. I always knew what was coming down the pike. The history at Marvel is, people become superstars, and then they leave. Some guys go off into advertising. Some guys go off to television. Some guys go to DC. And some guys just go off. But if anybody becomes a big superstar, chances are, they're going to leave.

Nrama: So you saw it coming.

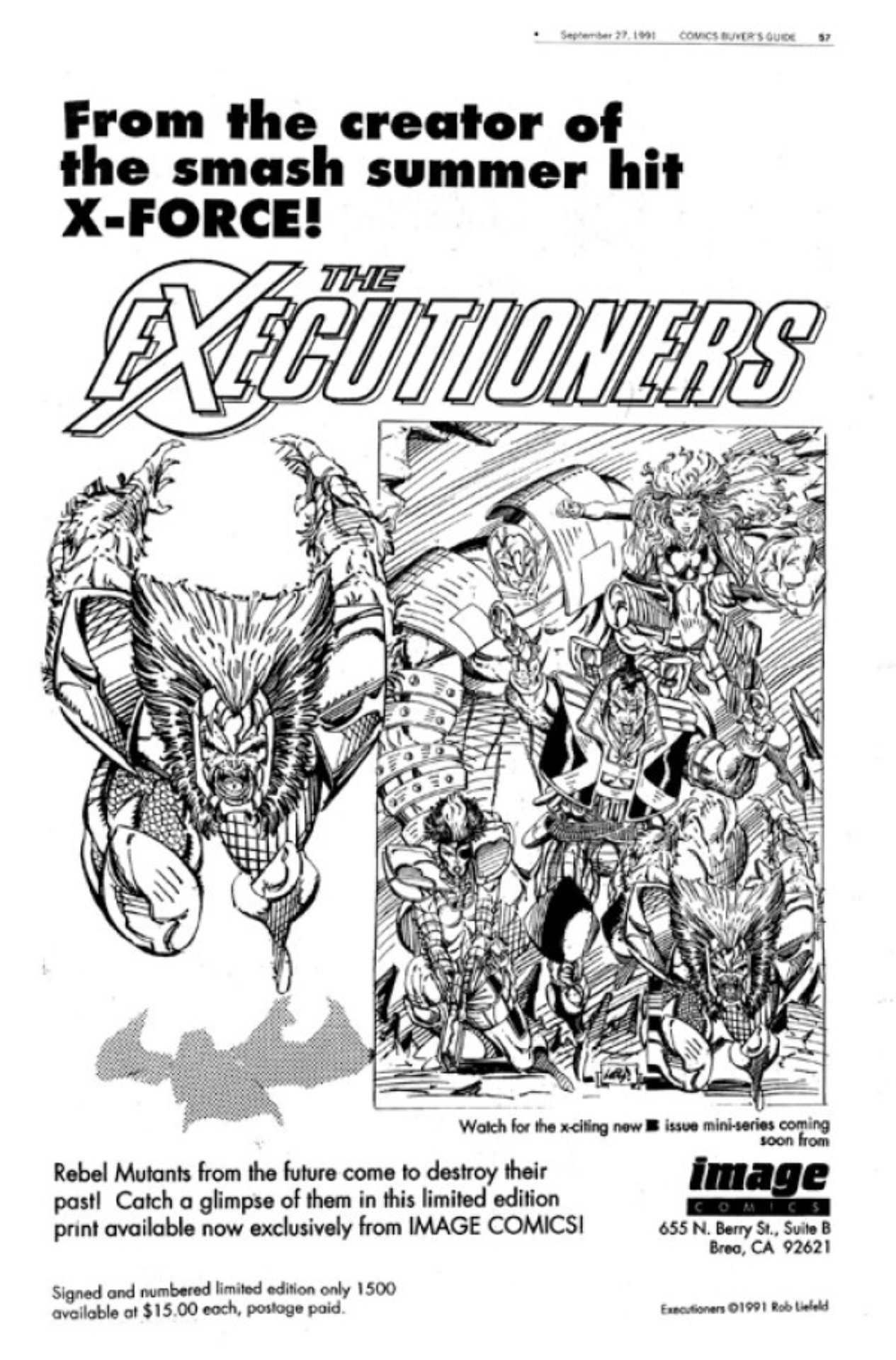

DeFalco: I knew they would leave. But what surprised me — the good thing that surprised me — they stayed in the industry and they created a new company. And not just a small studio, but it's been a major company. It's made up of creative people, and it's like United Artists that way. It actually happened, and I honestly thought it was a pretty terrific thing.

And what ended up happening was that the industry was big enough at that time, and the support for Image was strong enough, that they became a company that could publish other people's comics and gives other people the same chance they gave themselves. That's the good news.

The bad news was, for the first year, the publicity was all about how they had been mistreated at Marvel. And most people at Marvel were aware of how much money these guys made. We were walking around saying, "Boy, I wish they mistreated us the way they mistreated those guys."

But you know, publicity is publicity, and you've got to go with what works. In our industry, there's always a hero and there's always a villain. And Marvel was cast as the villain because if you were going to be the hero, you needed a villain.

Nrama: McFarlane has said he felt like he didn't have creative control over what he had to do in the comics he made. He said it wasn't just about the money, but it was about creative freedom.

Do creators have more freedom at the big publishers nowadays? Or is it pretty much the same way it's always been, where work-for-hire required that creative person to follow what the publisher wants?

DeFalco: There's always a conflict because creators tend to think short-term, and editors and the company have to think long-term. How does that story affect the character for the future?

When I was editor-in-chief, and when I was editor on Spider-Man, at least once a week, someone would come and say, "I've got this great idea for a story! Aunt May dies!!" When I was the editor of Spider-Man, I heard that pitch at least once a week, from somebody different. And I'd say, "Ok, and then..??"

From the creator's point of view, they can do a great emotional story where Aunt May dies. But editors have to think, what happens the issue after that? And the issue after that? Is it good for the franchise and the character? And that's what an editor has to do.

Nrama: You're working as a writer in a shared universe now. Do you feel like there's any more creative input than there was in, say, 1985? Has the editorial-creator relationship changed at all?

DeFalco: I'm not sure. Every once in a while I hear about somebody having a tantrum, and I wonder, what were their expectations? I haven't really noticed a change from where I sit. I think that as creative people, we've got to toss a lot of ideas at the editors. And some ideas they'll accept, and some ideas they won't accept. It's been that way since I can remember.

And if you have a lot of good ideas, then you have a lot of creative control. If you have ideas that the editor doesn't like, you have no creative control. It always depends on the individual creative person and the individual editor.

Nrama: We also heard from a few of the founders that there was a meeting where a few of these Image guys came in to talk to the powers that be at Marvel. Were they demanding anything? Or were they just saying goodbye?

DeFalco: I'll always remember this because there was supposed to be a big auction at, I think, Sotheby's. And I went to Terry Stewart, and he said, "you and I should go to that tomorrow." And I said, okay, we'll go to it.

Then about 6 o'clock that night, a lot of people were in town, and the Image guys were there, and I thought, "I haven't talked to Terry about whether we're going to meet here to go to Sotheby's, or if we're meeting there."

So, like a big jerk, I go up to Terry's office, and I just wanted to stick my head in and ask him where we were going to meet. And he was meeting with these artists - the guys who became the Image guys.

And I said, "Sorry to interrupt, but I just have one question."

And Terry says, "No, no, no, come on in. Come on in."

Nrama: Uh oh.

DeFalco: Yeah. Three hours of my life disappeared [laughs].

Basically, they were up there because they had decided that they didn't want to work on the Marvel characters anymore unless the company gave them certain concessions, and they wanted to create some things of their own. And it became just a big discussion.

The problem with the discussion - and I'm really simplifying it - is there was no united consensus. They wanted a better deal, but they didn't know what kind of deal they wanted. Did they want 80% of profits? Or did they want 80% of gross? Or did they want 80% of net? You know, what did they want?

And Terry and I had a very rocky relationship, but I'll tell you, he handled this thing perfectly. After three hours, during which I think I chewed off at least one of my arms, Terry turned to the guys and said to them, "Guys, you're obviously conflicted. You aren't sure what you want. Why don't you guys go and have a meeting, decide exactly what you want, and then tell us what that is? Then we'll either be able to give you what you want or give a counter-offer or just discuss it. But figure out what you want first, then we can negotiate. But it's hard to negotiate when you're not exactly sure what it is you want."

And they said okay. And everybody shook hands and went off.

Then I finally got my question answered about where I was going to meet Terry. And I went home.

The next morning, I go to Sotheby's. And I see one of the Image guys talking to a gentleman of the press. And I go over to him, intending to basically say, you know, "what was the purpose of that meeting last night?"

But as I get over there, he's explaining to this press guy how they're announcing Image Comics later on in the week. And that they had already signed a deal. And that sort of thing.

So I got a hold of him, and I won't say who it was, but I said, "Hey! If you already had a deal, why were you wasting our time last night for three hours?"

And he said, "Well, we thought it would be good publicity if we could tell the world that we went to Marvel Comics and they wouldn't give us a deal."

And I said, "If you already knew that, you should have clued me in and I could have gotten the hell out of there!" [laughs]

You know? I said, "Did you have to include me?" And he said, "Well, you weren't supposed to be there!"

That was really the only thing I kind of resented about the whole Image thing.

We were friends. And we remained friends.

Here's an example. There was one time at a convention where we were walking down the hall, and one of the Image guys was coming down the hall with his wife and his baby, and we all stood around, you know, playing with the baby and asking, how's it going? How's life? And all that other stuff. And a couple of panels opened up around us, and suddenly all the fans came out. And we suddenly realized, "Oh no! They'll see us fraternizing with the enemy!" And we started moving away from each other.

So, the Image guy says, really loudly, "And I'll never work for Marvel again!!"

And I said, "We don't want you anymore anyway!!" [laughs]

But you have to play the audience.

Nrama: I know that back then, there was some talk about some kind of unionization. And that's something that obviously hasn't happened at all. Do you think it ever could, or does it not make sense at this point?

DeFalco: You know, I don't know enough about unions and guilds and that stuff. But yes, for many years there was talk about a comic book writers guild or comic book writers union.

I have always thought that when the industry was making lots of money and everybody was doing well, that was the time to form it. And I always hoped the industry would form something like that.

But the trouble was, when things were really good, nobody was interested.

These days, where sales are not the greatest and guys are struggling to get assignments, it would be tough to form something like that. Everybody is competing with each other.

I've always thought that setting up some sort of real professional organization where you could get a group health insurance policy, which I think is something the industry has desperately needed for years, would be a great thing. And maybe have someone on hand to offer tax advice and that sort of thing.

[Newsarama note: In November 2021, workers at Image Comics announced their intention to unionize.]

Nrama: As the final question, Tom, what do you think the legacy of Image Comics is? It's probably never going to happen again quite like that, but how do you think the industry as a whole benefitted?

DeFalco: To me, the wonderful thing that Image brought is these guys - the original group of partners - put their money where their mouths were.

They championed the idea that creators should own their creations. And they created a company where that was possible.

I think that in itself is an amazing legacy. I applaud them for that.

It's no big secret that there's always been a question out there about Image: "How long will it last?" Certainly, in the early days, there were all sorts of betting pools and that sort of thing. Six months? A year?

Well, look at this. Twenty years! Image has outlasted a lot of major companies. They set out to prove a bunch of things. And they did.

Image Comics turns 30 in 2022: Newsarama looks ahead at what's coming including Saga, Astro City, Prophet, more.

Vaneta has been a freelance writer for Newsarama for over 17 years, covering Marvel and DC, and everything in between. She also works in marketing.