The Secret Origin of writer/artist John Allison

Webcomics, print comics... oh the Giant Days

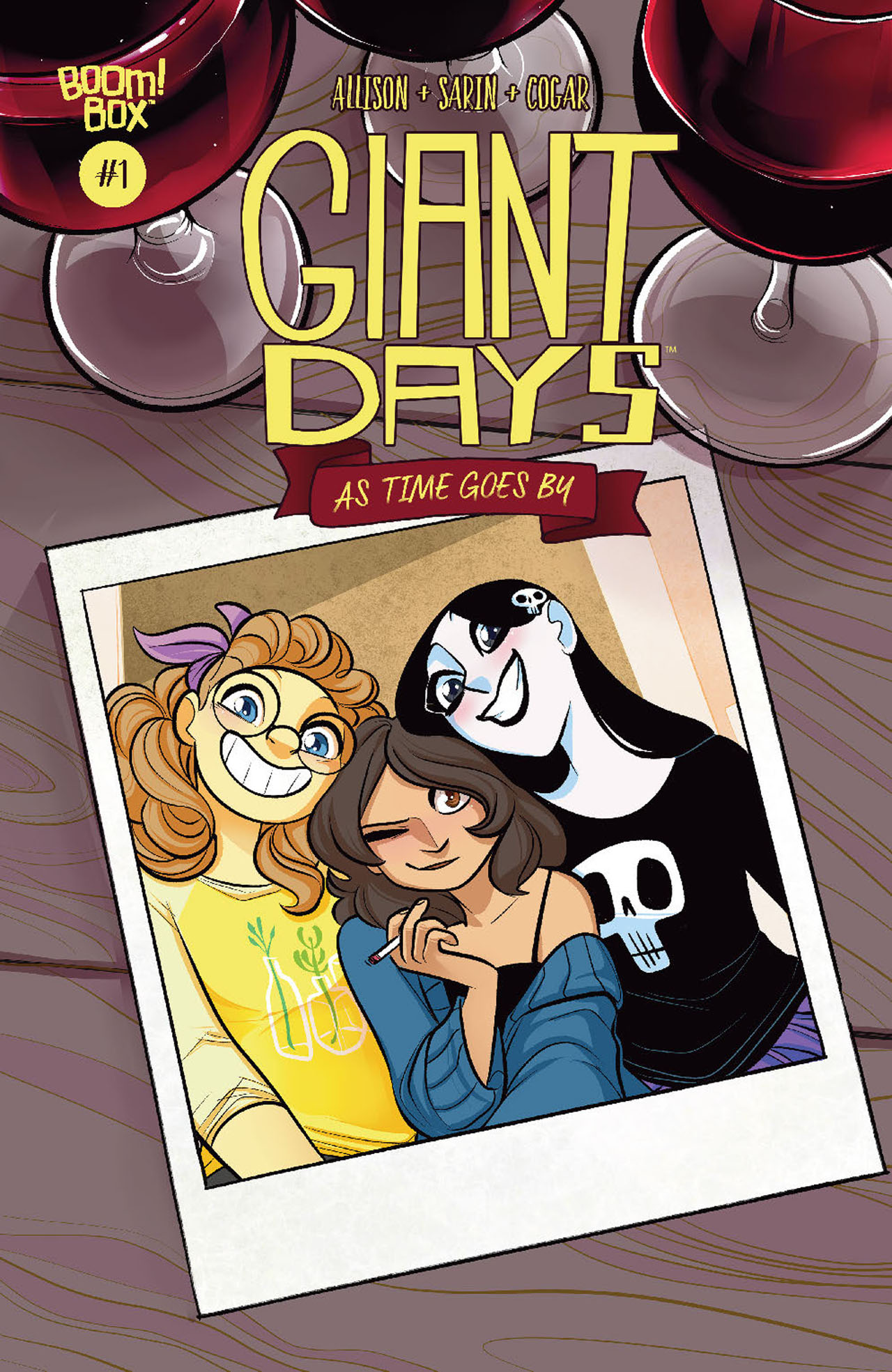

Best known for his work on the comic book series Giant Days, writer/artist John Allison has been on a roll with his current work - By Night and Wicked Things for BOOM! Studios, and Steeple for Dark Horse Comics.

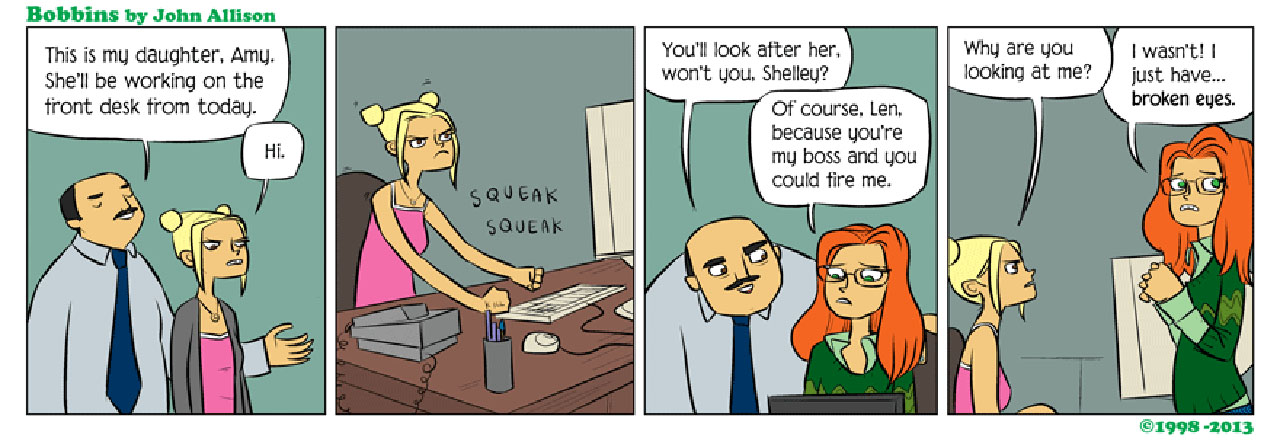

But before Allison was a prolific creator in comic books, he made his mark in webcomics - first with Bobbins, followed by Scary Go Round and Bad Machinery - the latter of which is still underway.

Allison has carved a space in print and webcomics with 'slice of life' storytelling and refreshing narratives - along with a signature art style. And now in the latest of our “Year One”-style interview series The Secret Origin Of…, Newsarama talks with the English writer about his career so far, how he broke into comics to begin with, and the differences between working on webcomics and print comic books.

Newsarama: John, to jump in, what made you want to work in comics?

John Allison: I genuinely have no idea. If you look at the comics I made as a child, I clearly wasn’t any kind of savant artist and storyteller. The UK scene is so small that I was never going to be able to work in UK comics, so I didn’t take things particularly seriously - the USA seemed incredibly out of reach. I think being on the internet when it first kicked off, in the late '90s, made the world feel suddenly much smaller, like these things were worth having a go at.

Nrama: Do you remember the first comic book you read?

Allison: This is quite hard. I remember my Dad bringing me a couple of DC comics - one was an issue of Superman where he rubs some alien pollen on his head so he can have a haircut at a normal barber. I think he has to escape a gorilla who doesn’t like his black hair. You will have to trust me on this. Another was an issue of Arion. I think this was about 1982, so I was probably six.

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

Nrama: What inspired you to create your first webcomic, Bobbins?

Allison: When I finished university, it took me a few months to get a job, so I spent the summer trying to look busy at my parents’ house so they wouldn’t get “restless” shall we say. I decided to put a submission packet together for US comic syndicates - that was how I started making the strips that I called Bobbins. I put the strips online and the rest is history.

Nrama: What attracted you to the webcomic form of storytelling?

Allison: A strip is a manageable unit of production, especially early on if, like me, you'd never successfully made a longer comic. The ease-of-access for readers and relationship with the audience were also two things that I perhaps took for granted until I moved to working in print.

Nrama: Did you always want to work in webcomics or was it a stepping stone to get into traditional publishing?

Allison: When I started, webcomics weren’t really a thing. It was an accident that I ended up part of the first wave. It was much easier to make money as a one-man operation than eking a tiny advance or maybe a feeble royalty from one of the indie publishers. My work wasn’t right for them anyway, not for a long time. Inevitably I became a self-publisher, which was a route into the traditional world anyway. It felt organic.

Nrama: Would you like to do more webcomics? Do you see a future in combining the traditional form of comic storytelling with webcomics?

Allison: I’m still making webcomics - I think it’s important to keep my hand in. Launching indie comics series is a hard lift through the direct market, the world is very unpredictable at the moment, and there is value in being able to do everything oneself. I’m unlikely to launch a new, long-running comic like Scary Go Round - it's harder to build an audience now than it was. I’m not sure I’m a good fit for Tapas or Webtoon, where there are a lot of young readers.

I think my hybrid webcomic/traditional approach has worked well for a few people - Molly Ostertag and Noelle Stevenson are two people who come to mind as having had great results. It’s a balancing act, getting your comics to do two jobs. It’s not particularly easy. Your print books can end up a bit dense, or your strips a bit sparse - there are two masters to serve. It creates pacing issues.

Nrama: What was your reaction to Giant Days' overnight success?

Allison: Relief. It was a relief to work on something that went beyond the readers I’d cultivated with my webcomics.

Nrama: How has your work on Giant Days helped you with your other projects?

Allison: It’s made it a little bit easier to pitch projects, but the structure of Giant Days isn’t actually something you can transpose onto other projects.

The luxury of a simple setup and an old-fashioned long run of issues made a lot of things possible that I (personally) can’t do with a six-issue limited series. You have two choices there: cram it in or fall short and hope they give you more. I read Little Bird (Image) and couldn’t believe what they achieved in five issues. I don’t have that gift.

Nrama: How was working on a book like Giants Days different from working in webcomics?

Allison: There’s a lack of feedback, I had to get used to that, because I always knew what people thought of my webcomics, from the comments section. But I enjoyed the ceremony of the monthly release - I like periodicals. I like waiting.

I like working with talented people like I did on Giant Days.

There were trade-offs. Part of me would have liked to have drawn it all myself - though I know it wouldn’t have been as good. I worked with genius artists and I am not a genius artist.

Nrama: What made you want to work on more slice of life storytelling compared to the traditional superhero comics?

Allison: Around 1996 I remember being alienated by the wall of cheesecake Image covers in my comic shop. Maybe I felt embarrassed by them in front of a friend. I don’t think I went in one again for five years. After the cheesecake wall experience, I got interested in slice-of-life, and comic strips, comics as a light, adult, entertainment form. I have been asked to write superhero comics and one day maybe I will, but it isn’t why I make comics, it feels like something I have to do, not a job.

Nrama: Why do you think slice of life is an important genre to explore not just in webcomics, but in mainstream comics as well?

Allison: It goes to my previous answer. I think superhero comics are fine, and I love so many of the artists who have worked in that genre, but the storytelling is inherently juvenile, yet the comics are designed to appeal to an aging audience. To truly understand them requires the monomania of a seven-year-old. They are not priced, or written, or drawn, for seven-year-olds. Slice of life, but more importantly, humor, is super-accessible.

Garfield was, for a long time, the second most borrowed book in US libraries behind the Bible. This is a form people just like - why is so much work done at the periphery?

Adults seem to love superhero movies to the exclusion of everything else but superhero comics don’t make sense to them - what they contain, how they’re sold, what it means to be seen reading one. Surely there’s a lesson there.

Kat has been working in the comic book industry as a critic for over a decade with her YouTube channel, Comic Uno. She’s been writing for Newsarama since 2017 and also currently writes for DC Comics’ DC Universe - bylines include IGN, Fandom, and TV Guide. She writes her own comics with her titles Like Father, Like Daughter and They Call Her…The Dancer. Calamia has a Bachelor’s degree in Communications and minor in Journalism through Marymount Manhattan and a MFA in Writing and Producing Television from LIU Brooklyn.