GamesRadar+ Verdict

A nailed-on awards contender that distills the essence of a legend thanks to a pair of career-best performances. These little ducks are off to the races…

Why you can trust GamesRadar+

At last year’s Venice Film Festival, Cate Blanchett roared into awards contention with her towering performance as a misanthropic conductor in Tár. This year, she can - literally and figuratively - pass the baton to Bradley Cooper, who disappears inside his performance as Leonard Bernstein.

As well as starring in this study of the legendary composer-conductor, Cooper is also director, producer, and - with Josh Singer - co-writer. Maestro’s screenplay eschews the cradle-to-grave biopic template, instead unpicking the fierce love and unconventional marriage at the heart of ‘Lenny’s’ creativity over four decades.

Bookended by a TV interview with Bernstein in old age as he tickles the ivories and declares “a work of art does not answer questions, it provokes them”, Cooper’s lyrical, musical (in terms of its dialogue, as well as Bernstein’s soaring scores) portrait doesn’t offer a finite encapsulation of a man, or spoon-feed us career milestones. Rather, it encourages both Bernstein fans and the uninitiated to spend time with an irrepressible talent, sexually fluid lover, and chain smoker, leaving details of time/place/specific works of art to be googled after the credits.

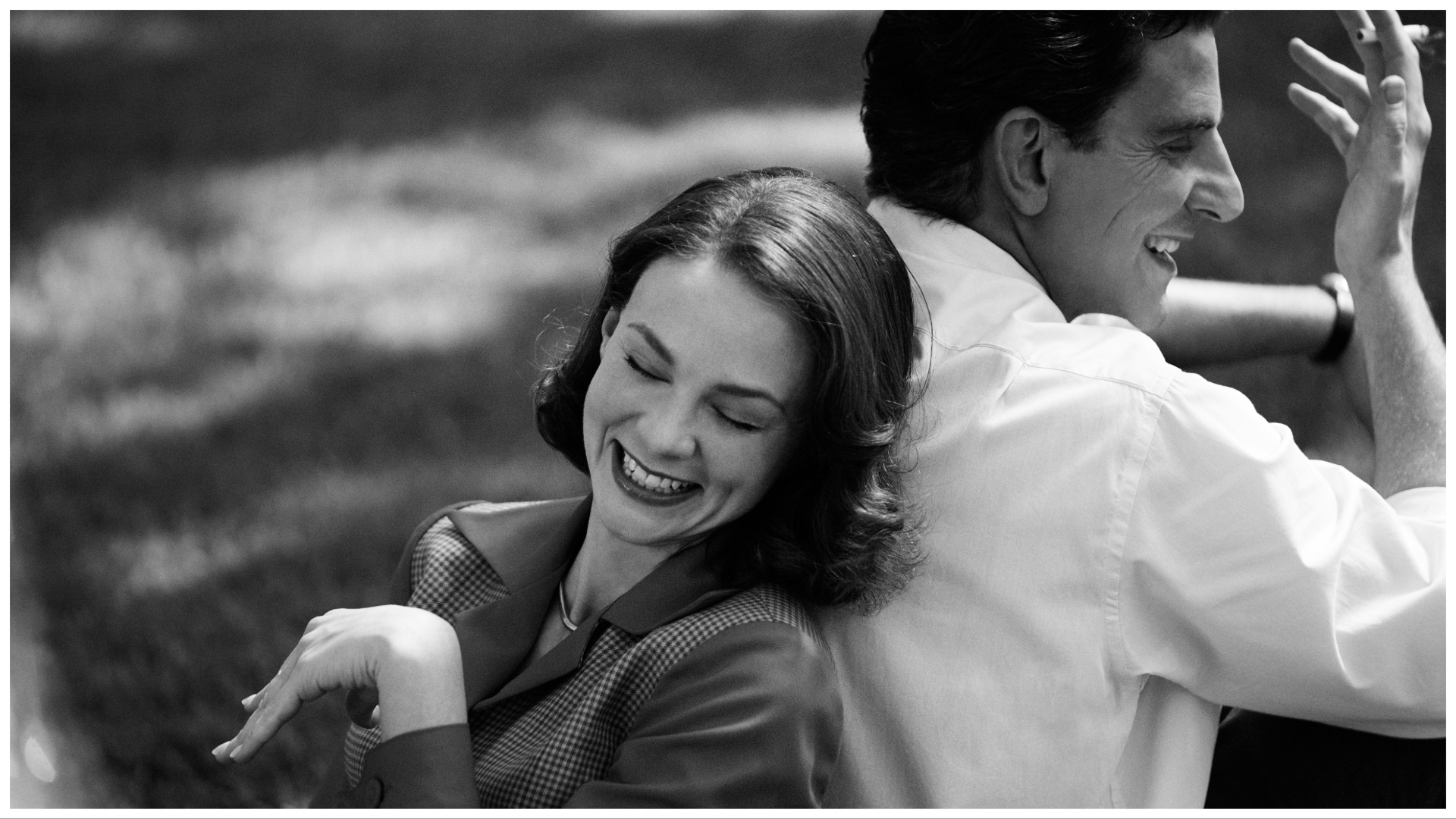

As the older Bernstein plays A Quiet Place and notes the emotion it evokes in him as he reflects on his much-missed wife, Cooper transports us back to Lenny’s big break – stepping up to conduct the New York Philharmonic in 1943. Lensed in monochrome Academy ratio, this segment also sees Bernstein sleeping with men, and Cooper sporting a controversy-stirring prosthetic nose that renders him avian. Before long we meet Maestro’s female lead, Carey Mulligan: and as soon as she appears as Chilean actress Felicia Montealegre, with her clipped transatlantic diction and knowing eyes, the sparks fly.

As Bernstein woos Felicia via an intoxicating On The Town song-and-dance number, the duo chatter like the two little ducks he compares them to. Him with his theatrical sing-song cadence, her with an idiolect forged from British schooling and a career in American talkies, their words overlapping and tumbling, their needs and parameters felt out. “I want a lot of things,” Lenny tells her as he’s whirled from her arms by a hot sailor. His voracious appetite - for people, for touch, for love - becoming the thread that runs through their marriage.

Felicia, supremely talented in her own right and adored by Lenny, works hard to stay out of his personal and professional shadow as black-and-white gives way to colour (and a wider ratio) when we hit the '70s, where we see the maestro juggling family and reputation. This is where the movie is at its best: the Bernsteins established, the nose less distracting in a face now full of prosthetics, the showy directorial flourishes of the first section giving way to long, single takes. There’s the tangible sense of a family unit - but also the first cracks of disharmony.

Cooper and Mulligan, friends off-screen, are organically believable as a partnership, dancing around each other linguistically in a way that’s thrilling to watch. A scene in a Manhattan apartment during Thanksgiving that begins with Cooper tripping over a table leg, then crescendos to a verbal opera as melodic as any of Bernstein’s works, offering two performers at their best; it’s surely the clip that will make the rounds come awards season.

While Cooper captures Bernstein’s softness, tactile, playful nature, and extreme enthusiasm, his performance makes most sense in opposition to and in tandem with Mulligan. And after she leaves the picture in a hugely affecting moment (one framed through a bedroom window), her presence is missed. Cooper’s uncanny depiction of Bernstein’s delirious, full-body conducting style is impressive and affecting as he leads Mahler’s Second Symphony and his own Mass, but it doesn't quite match the emotional whammy of the midsection.

An accomplished and classy follow-up to A Star is Born then, and one that proves Cooper is more than a one-hit wonder. But as an examination of artistic temperament, sexual voracity, and the patient women who love conductors, Maestro’s thunder has been stolen to a degree by Tár. Equally, some viewers might feel Cooper, despite using Bernstein’s diverse music like a Spotify playlist for his soundtrack, doesn’t provide enough career context to truly get a handle on his prodigious output. And those offended by the nasal augmentation, despite the Bernstein family’s blessing, may find it difficult to get past his beak.

Maestro will be released in selected cinemas in November and on Netflix on December 20.

More info

| Genre | Musical |

Jane Crowther is a contributing editor to Total Film magazine, having formerly been the longtime Editor, as well as serving as the Editor-in-Chief of the Film Group here at Future Plc, which covers Total Film, SFX, and numerous TV and women's interest brands. Jane is also the vice-chair of The Critics' Circle and a BAFTA member. You'll find Jane on GamesRadar+ exploring the biggest movies in the world and living up to her reputation as one of the most authoritative voices on film in the industry.