Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

Thomas Grip, co-founder of Frictional Games and the designer behind genre icons such as Penumbra, Amnesia and Soma, has a peculiar piece of advice for horror game creators: make it boring. "It's critical it's not too engaging," he says, "because then it's like playing Tetris while you're in the spooky mansion. The ghost is standing behind you, but you don't notice because you're too involved in the game of Tetris. You kind of want gameplay that is dull, repetitive or simplistic."

Brian Clarke, creator of 2022's The Mortuary Assistant (one of the best horror games ever) and now the in-development Paranormal Activity game, has a similar ethos. Explaining the tactics for building an effective scare, he says the goal is to focus the player on something innocuous and then suddenly break the silence.

"The key is that the player has something to do that distracts them from the elephant in the room," Clarke explains. "'I know there's something creepy in here – but I have to make sure that this swipe-card reader works'. The horror is almost secondary to the menial task."

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine #417. For more in-depth features and interviews on classic games delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge or buy an issue!

This approach characterises a certain type of horror game. Think of Slender, where all you do is walk through a (very plain) forest and pick up eight pieces of paper.

The Five Nights At Freddy's series, especially the earlier games, is similarly routine: check the cameras, monitor the power supply and, if you need to, shut the doors. If survival horror dominated the '90s, then this subgenre, which DreadXP head of operations Henry Hoare calls "blue-collar horror", is one of the biggest today. "The player develops expectations in their mind," Hoare says, referencing other examples such as Lethal Company and Repo, "and then you can subvert those expectations."

Unearthing nightmares

The key is that the player has something to do that distracts them from the elephant in the room

Brian Clarke

Towards the end of the '00s and during the early years of the '10s, horror games, in the mainstream at least, fell out of vogue.

Beginning with Resident Evil 4, Capcom transformed its flagship horror series into an over-the-shoulder third-person shooter. While the 'action-horror' hybrid was an exciting prospect in 2005, after the dour responses to both RE6 and Dead Space 3, the subgenre lost some of its power. At the same time, Konami was farming Silent Hill out to third-party developers, with varying results – if Shattered Memories and Origins were mild successes, the prestige of Silent Hill was undermined by Downpour, Homecoming and the widely disparaged HD Collection.

But while horror struggled in the world of triple-A, it was gaining new life elsewhere thanks to an emerging cadre of middle-budget and independent developers.

Amnesia: The Dark Descent wasn't the first game to pit players against an invincible monster, with no weapons to defend themselves, but in 2010 it felt like a statement.

If horror had swung to one extreme, with too many enemies, guns and explosions, Amnesia dragged it back to the opposite pole: no resources, no combat. This purified subgenre – 'run-and-hide horror' – gained further traction thanks to Outlast, Layers Of Fear, Alien: Isolation and dozens more.

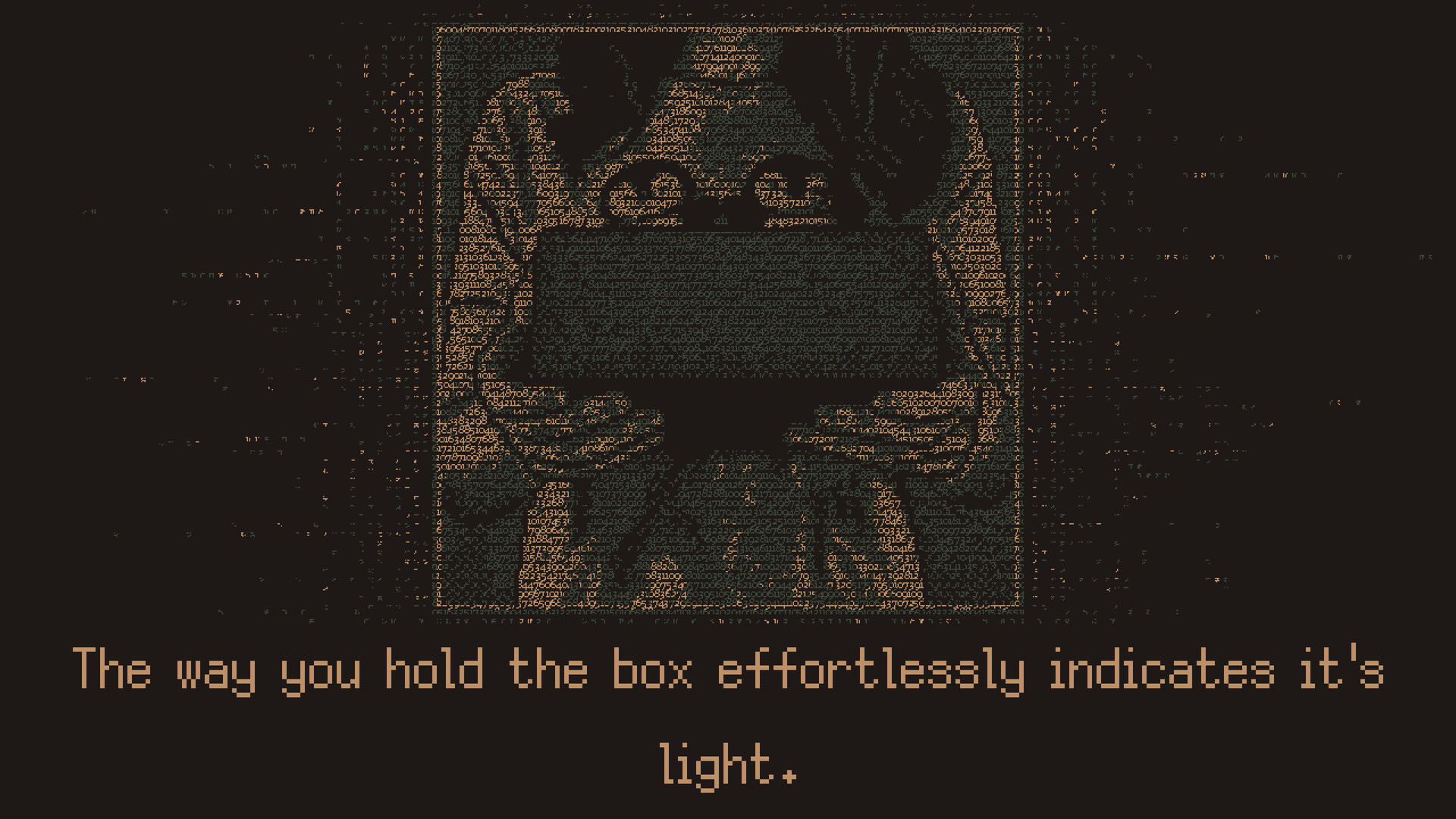

More recently, games such as Poppy Playtime and My Friendly Neighborhood – all inspired by the pioneering FNAF – have helped to settle and formalise another type of horror. The mechanics are straightforward; the story is drip-fed, and deliberately ambiguous.

If Twitch and YouTube Live also hit their strides during the past decade, 'mascot horror' has become the perfect streamer game, simple enough that you can easily talk and perform to the camera while playing, and with plenty of conjecture, lore and 'theorycrafting' to discuss with your viewers.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Combined with throwback horror games such as Crow Country, Back In 1995 and Signalis, and the sleazy splatterhouse work of developers such as Benedetto 'Puppet Combo' Cocuzza and Jordan King, the horror genre in 2025 comprises a rich combination of visual styles, mechanics and conventions – the traditional survival horror that predominated 30 years ago may still exist, but it's now complemented by several other horror types.

The genre's current popularity is the result of more than just range, however. Crow Country creative director Adam Vian puts it down partly to an inherent 'guarantee' that horror provides.

Sure shot

The save room is there for the moment that you have to leave the save room

Adam Vian

"A horror game is a promise of a meaningful, emotional something," he says. "It's saying: 'This is going to try and move you. You're going to be jolted by it'. It's also a counter to a bloated triple-A scene, where games are too long, and have too much 'stuff' in them.

"It's nice to make a game that has the scope of Resident Evil 2, something you can finish in two or three days, then maybe replay a few times. That's a model that we should never have abandoned."

So, how is it done? How do you craft a horror game, or, more specifically, the perfect scary moment? Think of the classics: the dogs smashing through the windows in Resident Evil; the mirror scene in Silent Hill 3; the dreaded Mr Tibbits' dead body fakeout in Condemned: Criminal Origins. Stark, sudden and almost certain to make you shriek out loud, these sequences also have something structurally and philosophically in common: they all catch you when your guard is down.

You might not think it, but rather than grotesque monsters or constant stress, one of the first keys to a successful horror game is creating a sense of calm. Developers need to lower your heart rate and keep you in a sweet spot where you're engaged, but not frustrated. That way, when they finally do spring a big scare, it has the maximum effect.

"You need a sense of place and a sense of tranquillity," Vian says. "The save room is there for the moment that you have to leave the save room. Without that, there would be no up and down, tension-wise – it would just be a flat line." "It's amazing how many 'cozy' places are perfect horror settings," Grip continues. "We spend a lot of our time making sure our environments are beautiful. We want to invite the player to stay there."

The element of surprise is also, of course, fundamental. A sudden stinger – a sharp jump scare, with a big noise and something leaping out onto the screen – may seem like a simple thing to create, but timing is everything. "It's good to ratchet up the tension to where the player expects something," Vian explains, "but don't give it to them at that point. Give it to them just after."

In Crow Country, Vian puts this theory into practice. One puzzle involves turning four gravestones so that each faces a specific direction.

While you're moving them, a grandfather clock is ticking loudly in the background, implying that, once the riddle is complete, something awful will be unleashed. Nervously, then, you align the headstones. The clock stops. And… nothing happens. But then, just before you leave the room – as you're still basking in a sense of relief – a giant monster bursts through the wall.

But this is a contained set-piece. If videogames are premised on freedom of exploration and player agency, and a good scare has to be carefully choreographed and authored, horror developers face an inherent challenge: how do you build the tension and then deliver the payoff at just the right moment if you also have to let the player roam? The Mortuary Assistant, with its bespoke 'Haunt System' created by Clarke, illustrates a convincing solution to the problem.

Clarke designed approximately 100 different possible scares, which reside in what he calls "a bucket" behind the scenes. As you're playing, depending on certain in-game factors such as your location, how far into the story you are and which scares you have or haven't seen already, these sequences may be pulled out of the bucket and "fire" on screen. As well as making each subsequent replay feel unpredictable, The Mortuary Assistant's Haunt System means players find the frights for themselves.

"In most horror games, you'll be doing something and then the camera is taken away from you, and that's the jump," Clarke says. "I wanted it to be like watching a movie and noticing something in the background. At the beginning of the game I'm pulling on small events, then I go to medium, then large, so you also have this growth. And there are other subsystems: even if two players get the same event, for one it might happen under the desk and for another it might be in the corner of the room. That's what gives it mystique."

Fear of the unknown

I wanted it to be like watching a movie and noticing something in the background.

Brian Clarke

Which brings us to another pillar of horror – and perhaps the greatest creative challenge for horror developers.

Once again, they have to reconcile an essential conflict between the nature and language of videogames and what we traditionally find scary. Games are built on systems and mechanics: press X to jump; earn 10,000 XP to gain a new level; defeat the boss to get to the next world. If the rules are too loose or ill-defined, a game might feel frustrating.

But horror, in contrast, is often rooted in the unknown and unknowable. We fear what we don't understand and can't see – the bogeyman is scary precisely because he exists in our heads, where we can project onto him all our darkest, subjective, imagined terrors. Once the abstract becomes tangible, it loses its grip on our psyche. "You know there's something hiding behind the door," Grip explains, paraphrasing a famous quote from Stephen King. "You open the door and it's a ten-metre bug! And then you're like, 'Oh my god! I'm glad it wasn't a 30-metre bug!'"

So, how do developers balance the systemic with the speculative? How can you build a playable, non-frustrating videogame, with firm mechanics, while also stoking players' fears of the incomprehensible?

"You should put in systems so that players have something to push up against," Grip continues, "but you should never make them so clear and defined that it takes away the player's imagination. Players want to be immersed, and want to feel like 'This is a big monster and I'm really being chased', but also they want to optimise their play style and 'win' the game. When it works best, the player is achieving the most optimized gameplay by acting like they're immersed."

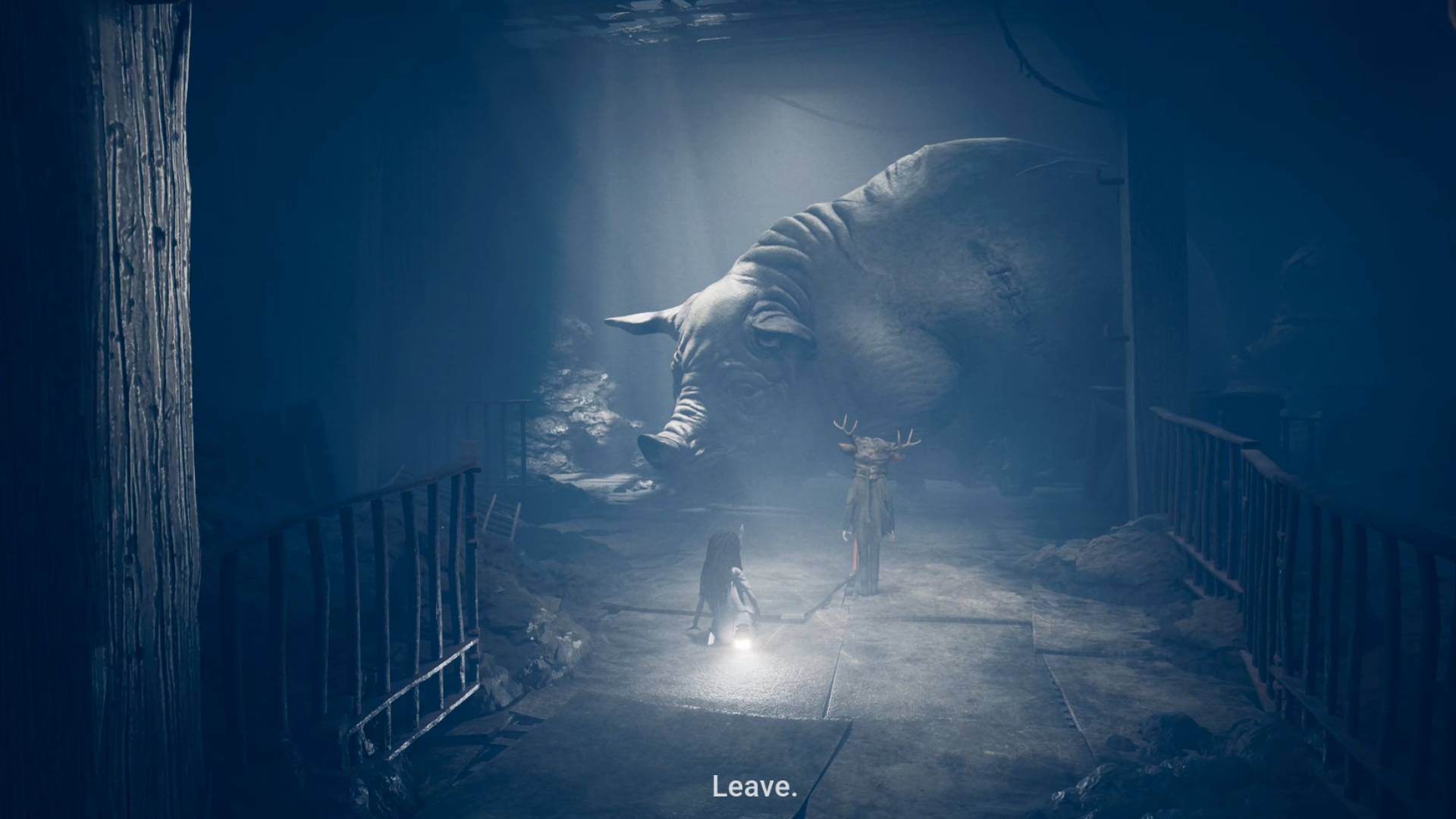

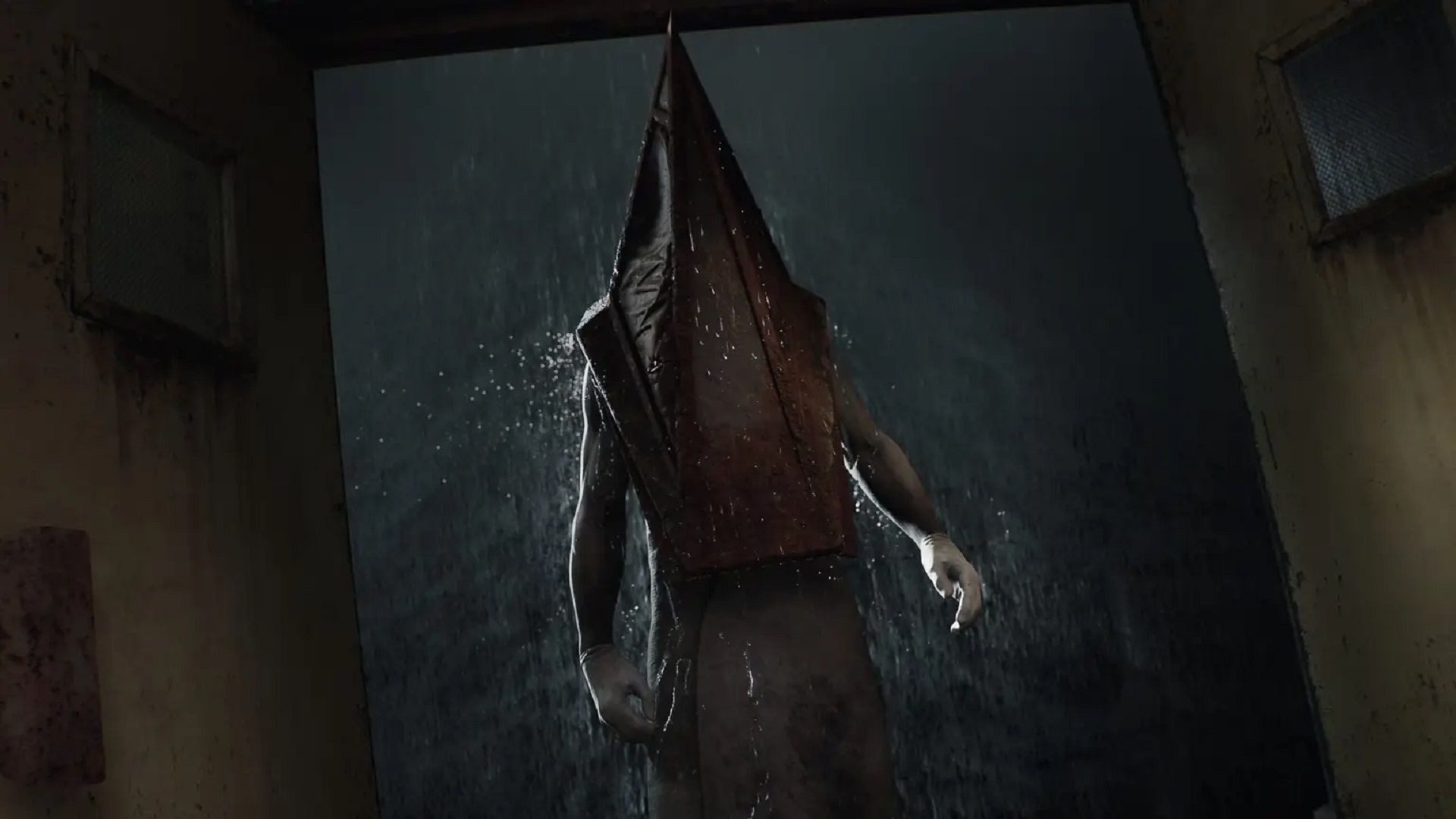

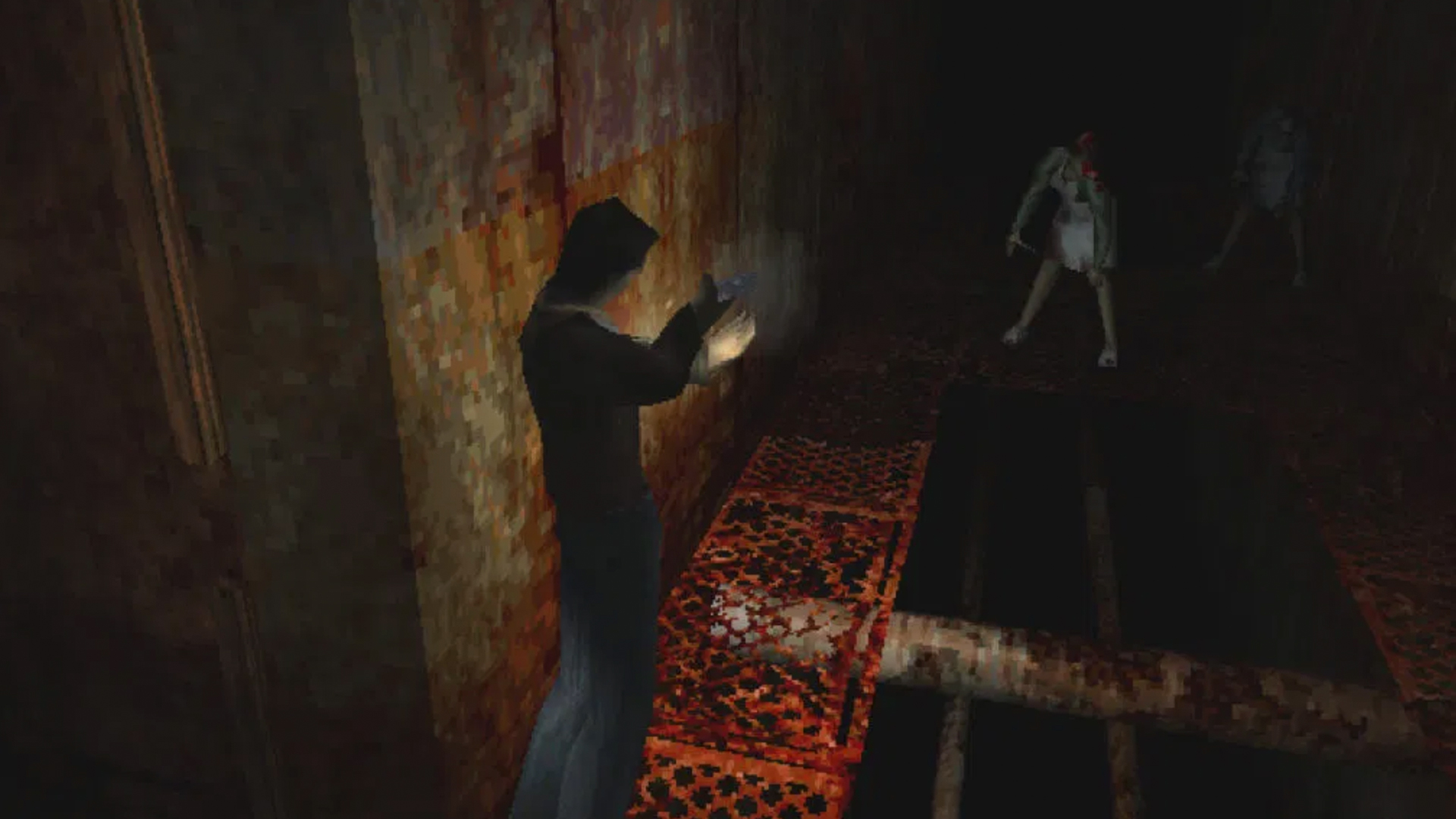

Grip uses the example of the first fight with Pyramid Head in the original Silent Hill 2.

Players have weapons, first-aid kits and a defined and consistent set of combat mechanics. When Pyramid Head attacks, you know how to defend yourself – press one button to aim, another to fire, and watch your ammo and health gauges. This constitutes the concrete, immovable, mechanical part of the scare.

But Team Silent also creates gaps in your understanding, gaps that your imagination can't help but fill with fear. Pyramid Head doesn't have a life bar. Though shooting it seems to have some effect, at the end of the 'battle' the monster doesn't run away; there's the sound of an air-raid siren, the bottom half of the room fills with a dark liquid, and Pyramid Head turns away from you and slowly walks into it until it's fully submerged, then vanishes. "The next time you meet Pyramid Head, it's like, 'Should I shoot it?'" Grip explains. "And dynamic choices make you the most anxious."

Do you leave the door open and pray Foxy doesn't kill you, or play it safe, burn through some power and risk a blackout before 6am? Should you go back and get some gasoline from the safe room, and maybe get chewed up by the zombies on the way, or just hope that you can get everything done in this area before this dead ghoul comes back as a Crimson Head? When you have to make a decision – when you have to act on something – you naturally feel more apprehensive and more scared.

Fifteen years ago, one of the most frightening things that horror developers could imagine was a monster that was unkillable; a game that flatly did not equip you to protect yourself or fight back in some way. But that creates a strange contradiction.

When you don't have any weapons and there isn't any kind of combat system, you also know, fundamentally, that you're never going to have to make an active decision – when confronted with an enemy, the only thing you'll ever be expected to do is to run away. If players only have a single choice, they're protected from any responsibility. Paradoxically, if you give players a weapon, it can make them feel a lot more vulnerable.

Where's my oar?

What makes cosmic horror scary is the idea that you have all the agency in the world, but good luck, because it won't help

Hunter Bond

"If you don't have a gun, you kind of know, 'Well, I'll be fine'," Vian explains. "There's this bit in The Last Of Us Part II. There's no combat, but then the tension starts to increase and you start finding ammo pickups. You're thinking, 'The rules of video games mean I'm about to be attacked, because why else would they be giving me ammo?' You don't get attacked. But the fact they start giving you ammo makes it better."

"What makes cosmic horror scary is the idea that you have all the agency in the world, but good luck, because it won't help," DreadXP director Hunter Bond continues. "If you have all the tools you need to interact with the environment and we haven't obfuscated your abilities at all, and yet you still find yourself up against something that you can't reckon with, that feels like cosmic horror."

Perhaps run-and-hide horror, of the type popularised by Frictional Games, is less fashionable or subversive now. Lunar Software's Routine gives you a taser-style weapon for defending yourself. Even Amnesia has a gun these days, used to great effect in 2023's The Bunker. Other horror trends, however, are still going strong.

Although Dead By Daylight dominates the world of asymmetrical PvP horror, knocking to the wayside would-be rivals such as Killer Klowns From Outer Space and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, the broader concept of co-op horror is being continually refined thanks to games such as Content Warning and The Outlast Trials. Mascot horror also appears to be alive and well: Five Nights At Freddy's: Secret Of The Mimic came out in June and chapter five of Poppy Playtime is ostensibly due in the near future.

Back to basics

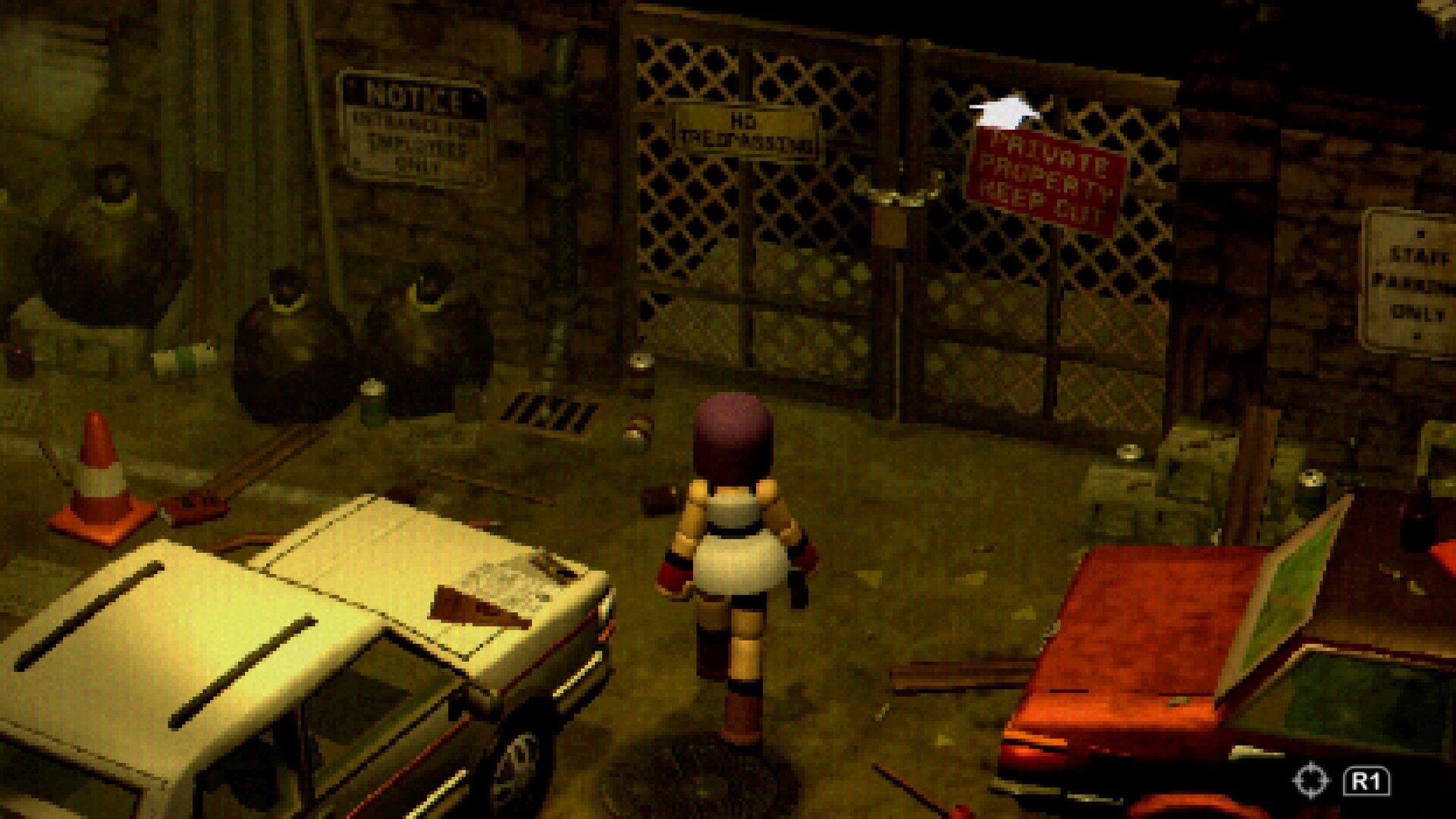

Another horror subgenre is also still thriving. You might call it throwback horror, the 'Resident Evil-alike' or 'boomer' horror – think of Heartworm, Conscript, You Will Die Here Tonight, Hollowbody and, of course, Crow Country, games that have PS1-inspired visuals and make use of classic conceits such as fixed camera angles and limited inventory space.

At least to some extent, the success of these types of games is a byproduct of players' and developers' nostalgia. But there's more to this trend than hollow sentimentality. For some developers, making a game that looks like Resident Evil is just the setup for a bigger twist.

"I don't think that the wave of stuff inspired by the '90s is about replicating so much as following personal inspirations," Hoare says. "But it also speaks to something that horror is good at, which is subverting expectations. If players have nostalgia, they also have expectations for games of that time, and you can subvert those."

Jordan Mochi's Conscript may use the mechanical rudiments of survival horror, but they're redeployed for a story about World War I. Signalis, by Rose Engine, also has a lot in common with old-school Resident Evil and Silent Hill, but what we might derisively describe as the game's nostalgia baiting is really just the feed line for a more complex, and frightening, cautionary tale about dwelling on the past.

If one of the fundamentals of horror is taking something familiar and comforting (say, a nice suburban house) and turning it into a grotesque of itself (making it haunted by the ghosts of the family that was murdered there), the beloved games of our collective childhoods make fertile soil. It's what you remember fondly – but with rows of hidden teeth.

It's achieving the most with the least

Hunter Bond

Looking beyond nostalgia and the throwback subgenre, however, there is a deeper and more complex 'need' for lo-fi or (apparently) low-budget visuals in horror games.

We go back to that idea of the power of the imagination. It's not about what we can see; we're scared of what we can't see. Modern, big-budget, quasi-photorealistic graphics fill in the details for us. Visuals that are lower in resolution or more abstract create cracks in our comprehension.

"I think when we hit PS3 graphics, all the mystery was gone," Vian says. "On the PS1 and PS2, things are kind of flickering and you can't see what it is exactly, and that's just scarier." "Those dogs, man," Bond says, thinking back to the first Resident Evil. "It's a dog-shaped blob. It's not rendered sharply. But it's achieving the most with the least."

Perhaps this is why there are so many independent and solo-produced horror games: if you don't have much money, or even much game-making experience, horror naturally lends itself to a rough and raw kind of design. You can play on the fond, childhood memories of players and also stir their imaginations with a low-res art style.

"Imagination drives horror," Sniper Killer and Night At The Gates Of Hell developer Jordan King says. "When describing my style, I just use the term 'low poly'. It's a quick and messy style but I think thematically it fits with the experience being presented."

Hoare has another way of explaining this. When we ask why horror is one of the most accessible genres for budding developers, and why players, more than forgiving them, actually relish and identify with certain technical eccentricities, he puts it simply: "Horror as a genre is more forgiving of the seams."

Guess who's back

Imagination drives horror

Jordan King

Almost 30 years since Resident Evil formalized its most recognizable tropes, and a decade and a half after Amnesia gave the entire genre a soft, spiritual reboot, the horror game seems to be back in favour with gaming's mainstream.

Beginning with Resident Evil 7, a more traditionally designed survival-horror game, and following it with a trio of crowd-pleasing remakes, Capcom has carefully reestablished the core of Resident Evil – if Village strayed too far from the series' fundamental principles, the next upcoming horror game in the franchise, Resident Evil Requiem, already feels like an attempt at recentring things.

Silent Hill is also back, courtesy of The Short Message, the Silent Hill 2 remake and Silent Hill f, and there are even cautious attempts in the mainstream space to launch new horror properties, such as Cronos and Reanimal. If the general audience lost faith in the horror genre during the mid 2010s, it seems the successes of medium-budget and independent titles have incentivised a comeback.

"We released Crow Country in May 2024," Vian says, "and I'm not saying we caused anything, at all, but it feels like since then the floodgates have opened. It's happened on both sides of the coin. Indie horror is doing great and triple-A horror is doing great."

Alongside that optimism, though, Vian has cause for concern. Reflecting on how many horror games have been released in recent years – or even during the past 12 months – he's worried that Crow Country and its developer SFB Games may have been "on the last helicopter out of Saigon", and that the current popularity of horror games might not last much longer.

Indie horror is doing great and triple-A horror is doing great

Adam Vian

Jesse Makkonen, a solo developer whose work includes the trippy 2D adventure Afterdream and psychological horror series Distraint, is similarly cautious.

Despite receiving glowing reviews on Steam, his latest game, visual horror novel Without A Dawn, has struggled to find an audience since it was released in May. Though he has no illusions that the game is "a heavy experience, which surely puts many people off," Makkonen also says that it's getting harder for new titles to be noticed in an increasingly crowded horror genre.

"Since there are so many games coming out, making a successful one requires market research and a design tailored to the market, which I find incredibly uninspiring," he explains. "I've been just making the best games I can and trying to market them to the best of my ability. It's increasingly difficult to survive this way, though."

And is big-budget horror really 'back', or are triple-A developers still playing things comparatively safe?

I don't know if I would call it a resurgence – yet.

Brian Clarke

In 1999, Silent Hill felt unusual, dark and experimental. It had a distinctive visual style and offered a fresh take on terror: where Resident Evil had been rooted in body horror and monsters, Konami's effort was psychological and surreal, and played on the twisted illogic of bad dreams.

It was a mainstream game, certainly, but one with bold ideas. We may be seeing positive signals from the likes of Capcom, Konami and the other major horror names right now, but some developers have yet to be convinced of the genre's big comeback.

Dull, repetitive or simplistic mechanics might be a good way to lull players into a false sense of security, but if we're talking about the long-term success and ultimate survival of the broader horror game genre, Thomas Grip thinks it's going to take more unconventional ideas to keep things alive. "I feel like we have a lot of lizard-brain stuff," he says. "Playing a lot of horror games now, they're fun, but not really saying anything. I would like to see more horror games where it's not just scary, but it's interesting."

"It's awesome to see more Resident Evil and Silent Hill, but they're all safe spaces that these developers have already established," Clarke concludes. "It lies dangerously close to remake after remake after remake. Until I see a big company make a brand-new horror IP that feels like it's really out there and trying to do something, I'll feel like we're heading down the same route and rehashing the classics. I don't know if I would call it a resurgence – yet."

Explore the best survival horror games of all-time if you're hungry for more chills and thrills (and inventory management(

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.