Aztek: remembering the DC "hero for the new millennium"

Grant Morrison and Mark Millar talk about their Aztek series and their aborted plans for more

It's time to go back-issue diving for Aztek: The Ultimate Man.

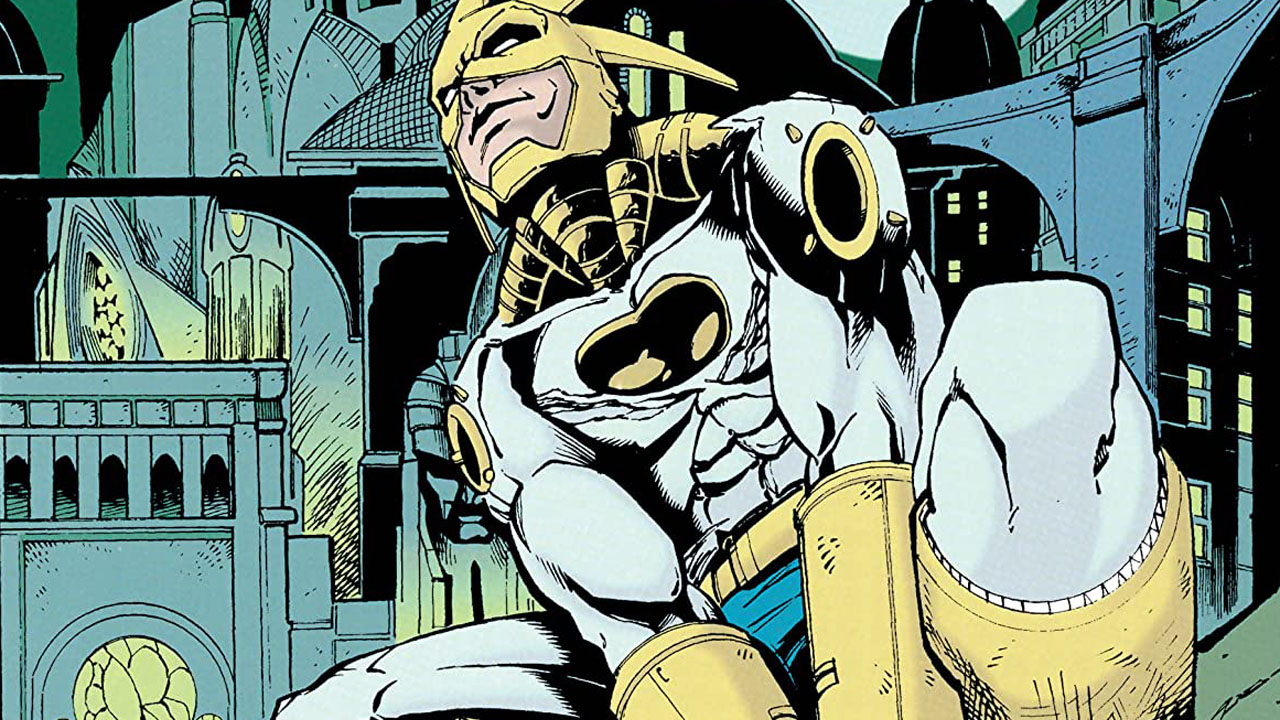

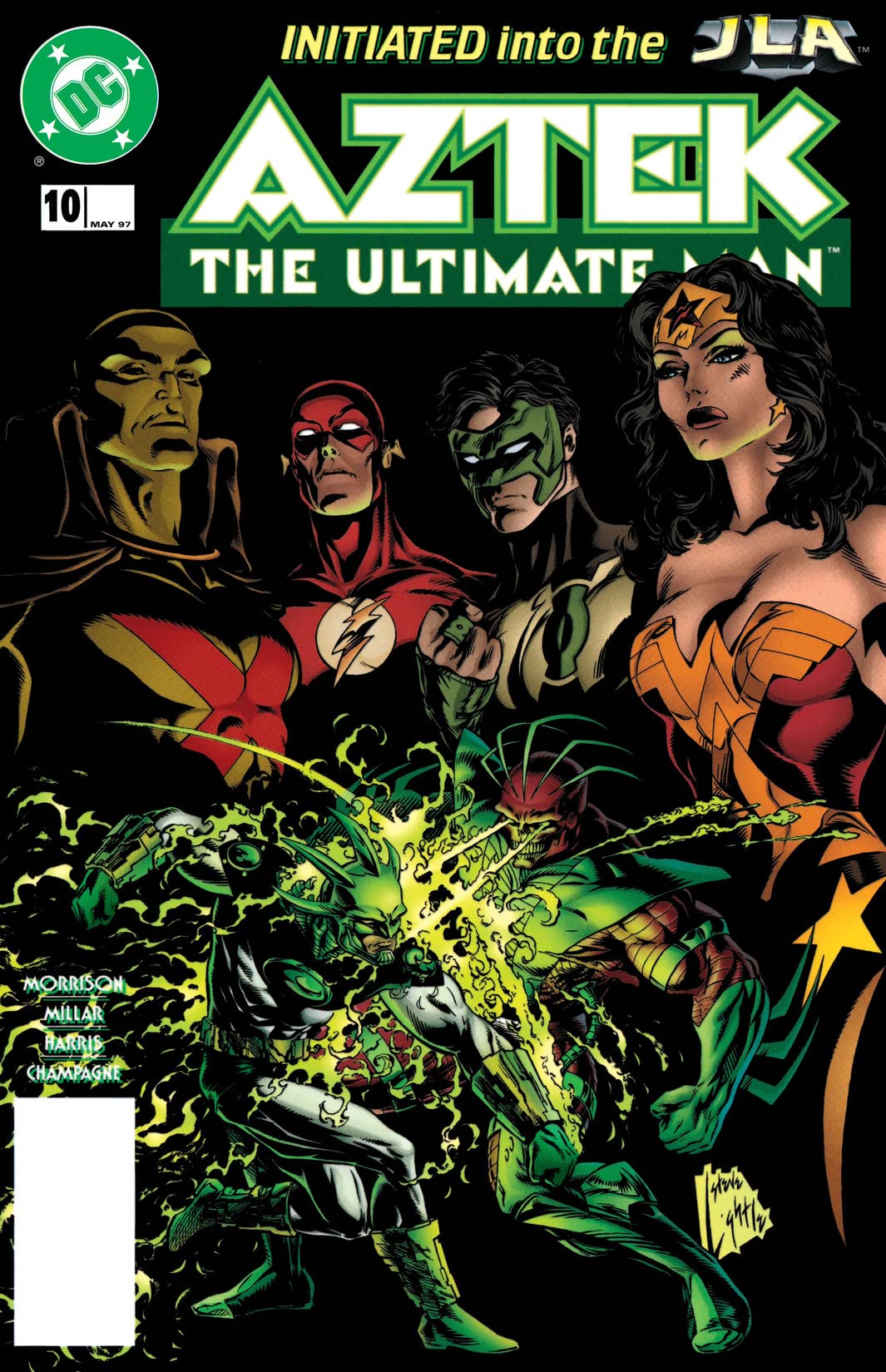

Published for 10 issues by DC from 1996 to early 1997 as a series, Aztek contained much of the quirkiness and mad unpredictability that flavored Grant Morrison's Doom Patrol a few years before, while at the same time, carried a through-line of Silver Age-style heroics from Morrison, co-writer Mark Millar, and artist N. Steven Harris.

Looking back on it now, the series and the character are as fresh as anything coming from DC, and a little more accessible than Morrison and Mark MIllar's Skrull Kill Krew at Marvel, which brought a true British punk feel to comics. No, Aztek was a series with a cool hero, a cool setting, with worlds of potential that felt somehow… different.

Looking back at Aztek, you can see strains of themes and ideas that are often used and became well-accepted in in the early '00s titles – the beginnings of Morrison's 'widescreen' approach to heroes is here, as well as heroes taking a no-nonsense approach to villains. Heck, it feels just like a modern book.

But it came out in 1996, so of course, it was canceled.

Like DC's Captain Comet, Aztek: The Ultimate Man was ahead of its time, pushed out on a market that had just seen its sales sliced roughly by half during the previous year, sending many fans into the familiar and, well, predictable arms of the traditional, mainline superheroes, and away from titles like Aztek. While his series ended with issue #10, Aztek was moved into the JLA from issues #10 - #15 (he left after the 'Rock of Ages' storyline), and returned for Morrison's final arc, 'World War III.'

The following quotes from Morrison and Millar come from an interview that, unfortunately, never saw the light of day, due to the title's cancelation back in 1997. It's a fascinating look at where both the creators were near the series' end, and their thoughts on how this series could help to lift comics up again.

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

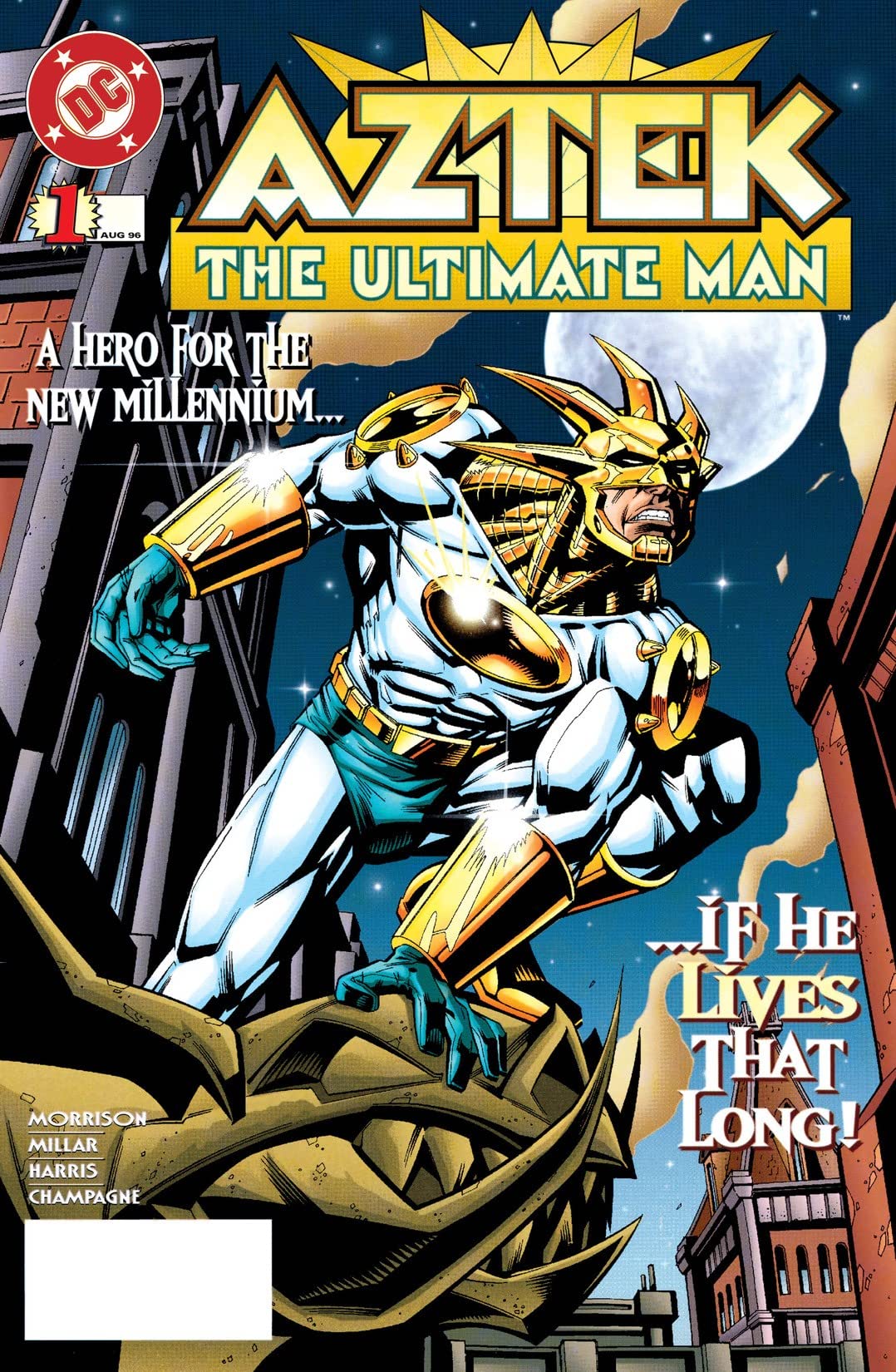

Making a New Hero

When Aztek debuted, the comic market was slowly coming out of its self-imposed grim and gritty era, with Mark Waid's run on Flash largely credited for promoting the idea of upbeat, shiny heroes. Aztek followed the lead.

"The lighter touch came out of a dissatisfaction with grim and gritty, which is what everyone's been doing for the last few years," Morrison said in 1996. "When I did Animal Man way back, that was only two years after Dark Knight, and already I was sick of that stuff. It's just time to get back to the kind of superheroes we like, a guy who would lookout for people, who would take the time to rescue a kitten or a lost lizard. We just wanted to do a nice guy again, because we were so tired of doing these miserable guys in trench coats with five o'clock shadow and ponytails."

"We also wanted a challenge of doing a new superhero who would work, and that remains to be seen, but we were looking around and thought that Green Lantern was the last superhero comic in the last 30 years that's worked at DC, and hasn't been canceled. We wanted to create a new superhero that was actually viable, and was interesting enough, and had a visual look that was distinctive enough that it might survive. That's why we created it at DC, cause we wanted to create a character that could be long-running."

Dusting off the recipe for the classic Golden and Silver Age and pulp heroes, Morrison and Millar pulled out the traditional ingredients:

- a hero following in the steps of his father

- trained by a mysterious society (the Q Society)

- the last in a long line of heroes, pure motives

- square-jawed

- alter ego of a naive, awkward teenager

- brilliant in numerous fields from philosophy to medicine

- a connection to a threat that was supposed to one day destroy the entire world

Heck, Aztek was following formula so dead-on, his name 'Aztek' was given to him by a reporter in issue #2. Sound familiar?

"He's kind of the Doogie Houser of the superhero community," Morrison said. "He's so painfully naive, he's almost impossible to talk to, but he's the ultimate man in terms of the mental and physical training he's gone through. He's the weird kid in the back of the class. The 'class nerd' of superheroes."

Aztek is the kind of guy who would stay up all night looking for a lost pet (issue #4) just because it's the right thing to do. He's also the kind of hero who would give muggers some money so they would stay out of trouble (issue #3). But since he was raised by a secret brotherhood in the Andes as humanity's savior, his motives are beyond reproach, but his contact with society has been somewhat limited. To call him naive is an understatement.

"He's this fantastic warrior who's read every book of philosophy that exists," Millar explained. "But he can't figure out how to order a pizza, or ask a girl out. So he's this great hero with a horrible social life. Sadly, Grant and I wanted to create a character we could empathize with."

The quick background of the character included ties to Aztec mythology (since virtually every other mythology has been mined for heroes), was that Aztek was the latest in a line that stretches back 2000 years, of warriors trained since birth to battle Tezcatlipoca, the Aztec god of darkness that makes the Western view of Satan look like a pretty tolerable guy. According to Aztec mythology, Tezcatlipoca would return to battle the embodiment of light - the warriors of the Q Society.

"The god of darkness was imprisoned 2000 years ago, but they knew they couldn't hold him, and he'd be back, and when he came back he was going to destroy the earth and create a new earth in his image, so this society was formed to prepare a champion, and every generation they have a new one since they don't know exactly when the guy's coming back," Morrison said.

"It's now gotten to the point that the last champion who should've faced it was Aztek's dad, and some mysterious thing went wrong with him, which we'll find out in the series, and they killed him, which Aztek doesn't know about. He's only 19, and has been stuck with the task of dealing with the thing because they've realized that it's coming back within the year, and it's chosen this city called Vanity to make its return."

The Touch of Vanity

Two of the pioneers of a technique that would be used later by the likes of James Robinson with Starman's Opal City among others, Morrison and Millar created a new and unique fictional city within the DCU, Vanity. Giving the city its own unique history (laid out in the series as well as the occasional essay or faked newspaper article in the back of the issues), Morrison and Millar made the city a character in itself, albeit an evil one that corrupts everything it touches. It was the perfect home for the bright shiny hero to prove his mettle.

"We took the idea of this really nice guy, a superhero from the '60s in terms of his morality, and put him in a city that embodies all of the worst aspects of what we saw happen to superhero comics in the last ten years," Morrison said. "The criminals are psychos. Even the heroes are psychos in Vanity."

Or as Millar succinctly puts it: "Aztek's the world's nicest guy in the world's shittiest city. Everybody always says that a town is worse than Gotham, but it never really is, there are just more back alley muggings. In our plan Vanity is actually much worse, and the evil is built into the city's architecture. Every priest is a pervert, and there's a monster in every family. The city was built by Charles Vane, who was a worshiper of the dark, and he wanted to create Hell on Earth."

The effect of Vanity was so pervasive that even its best heroes (and visiting heroes, as Green Lantern found out in issue #2) became corrupted and evil. In essence, Vanity gave Morrison and Millar a chance for their hero to strike out against the 'evil' that the two felt had infected the comics industry.

"No matter how good you are, when you come to Vanity, and you end up a bastard," Millar said. "Bloodtype and his girlfriend were originally Mr. America and Miss Liberty, and within a few months they became Bloodtype and Death Doll. The city just had this terrible effect on them, so the people see Aztek as a real hope, but at the same time, they really don't hold out much hope for him to do much. It's a matter of will he change the city, or will the city change him, and he'll end up as big a bastard of the others."

All in all, Vanity was a perfect place for the Aztec god of darkness to make its return. In fact, the city's creator Clarence Vance, designed it as a lens to focus the evil that would one day return to the Earth. In vanity, Morrison and Millar presented an analogy for the then-current comics scene – normal heroes were being and had been transformed into twisted, dark versions of themselves. Literally and figuratively, Aztek was here to fight against that threat and trend.

The Adventures of the Hero as a Young Man

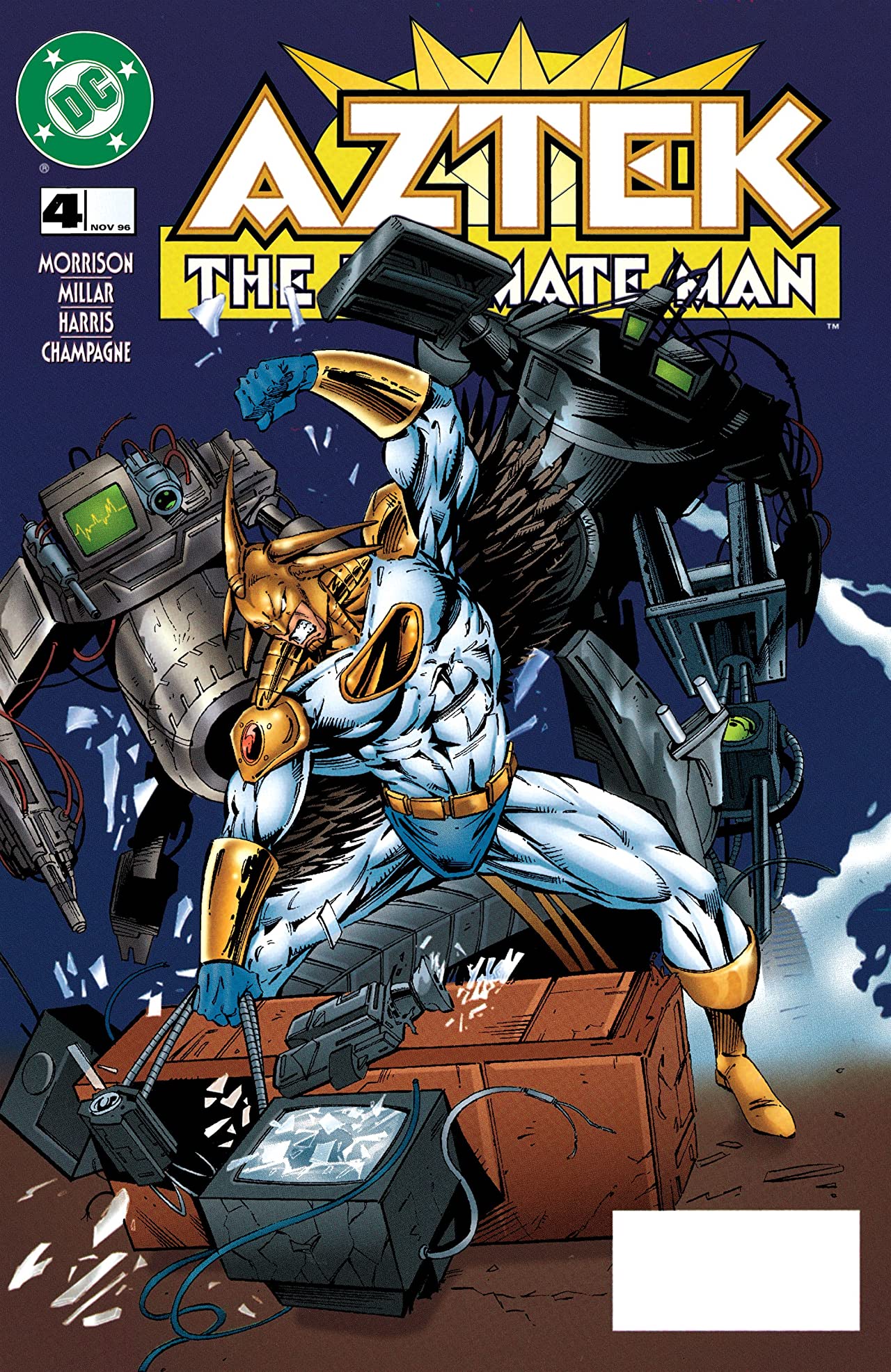

From issue #1, Aztec was on the manic Morrison/Millar fast track; each issue loaded with hundreds (if not Morrison's later, characteristic, thousands) of ideas per issue.

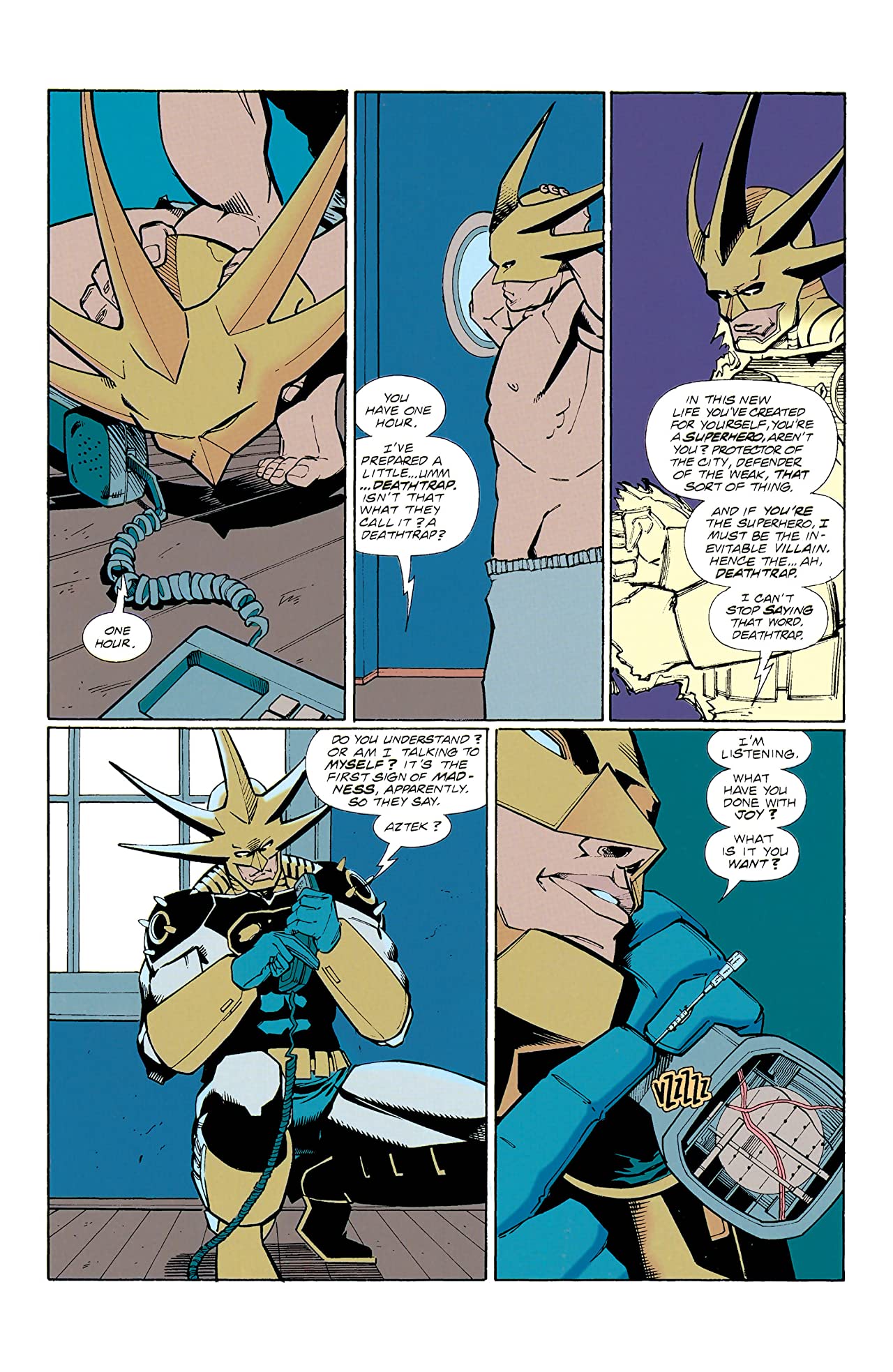

In issue #1, Aztek battled the Piper, a villain that resonated to Morrison's Doom Patrol days. After all, here was a villain whose shtick was animated smoking pipes. In his attempt to bring down Piper, who was being extorted by the shapeshifter Synth (who alternated between geraniums and moron every other day), Aztek battled Bloodtype, the perfect epithet spewing, gun-toting mockery of any given Image character. The Piper was killed during the battle, allowing Aztek to assume his civilian identity, Dr. Curtis Falconer (the noble, soaring bird reference in his last name was no coincidence). Falconer was days away from beginning his new job at Vanity's St. Bartholomew's Hospital, so Aztek became the city's newest doctor, as Curt Falconer. Yup – people thought it was odd that he was just 19, but let it pass when they saw his skill as a doctor.

After establishing his secret identity, Aztek encountered Green Lantern in issue #2, giving the creators a chance to poke a little fun at the still relatively new Kyle Rayner. It was 1996, after all, everyone was poking fun at Rayner. During their meeting, Aztek took Green Lantern's ring from him, again, subtly establishing himself as a hero to be taken seriously. After that, he was targeted for revenge by Bloodtype's girlfriend, Death Doll, and then encountered the Lizard King in #4 and #5 (no, not Jim Morrison), a warrior who was Aztek's father's second, ready to step into battle if the hero ever fell. Seeing the young Aztek as far too naïve for the job, the somewhat mad Lizard King took Aztek's helmet, a move that ultimately drove him mad.

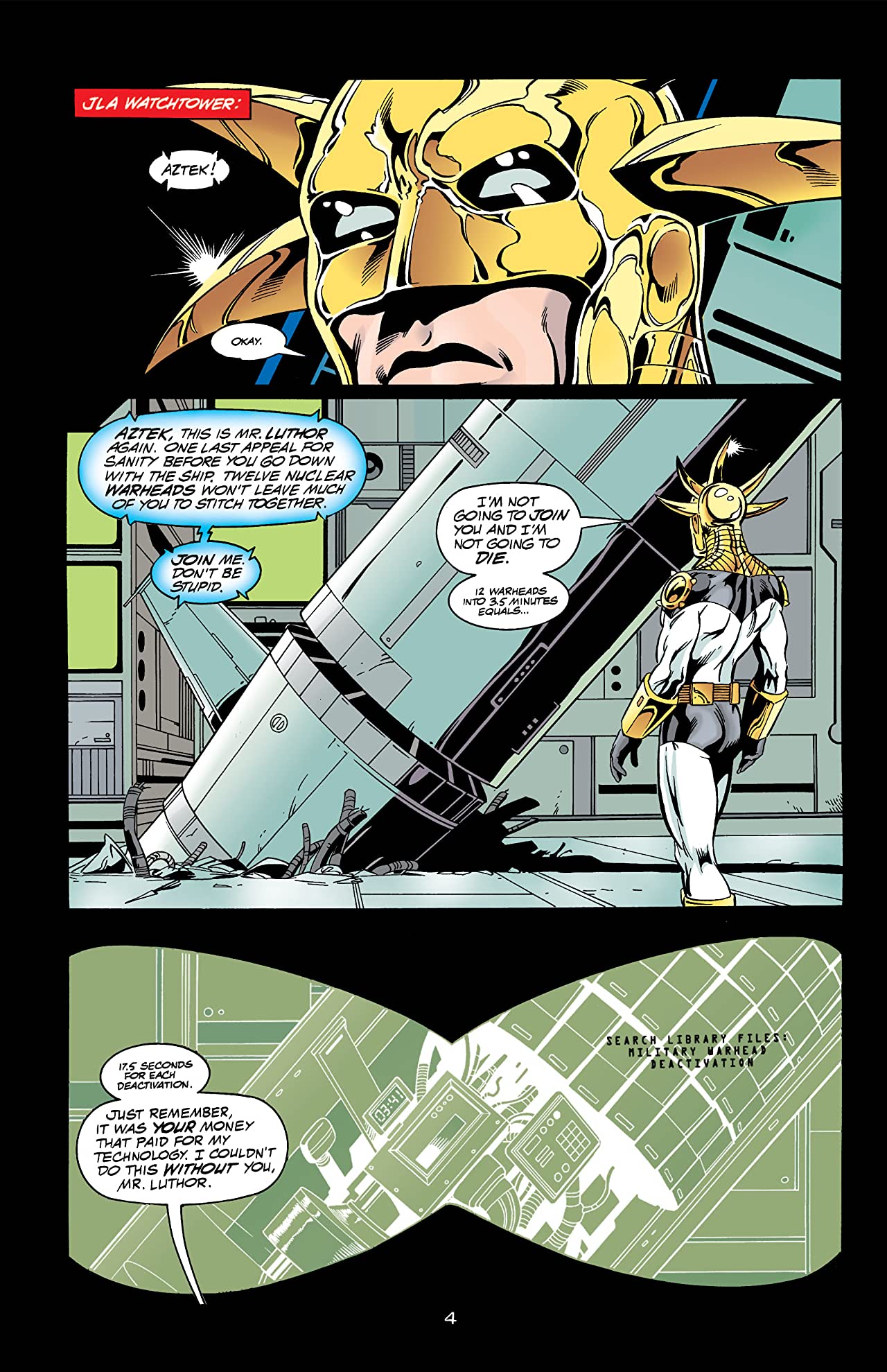

The young hero joined with Batman to battle the Joker in issues #6 and #7 ("He likes to vacation somewhere that's worse off than Gotham," Millar said.), earning the endorsement of the Dark Knight, returned to the Q Society for repairs in #8, giving some of the obligatory background exposition of his training and mission and also revealing that Lex Luthor has ties with the group, setting up a huge conspiracy that, if the series had lived, been shown to stretch throughout the entire DCU. The obligatory nod to Superman (along with commentary on Superman's then-current change to his electric blue version) followed in issue #9, and by the series' final issue, #10, Aztek was the JLA's newest recruit.

Peppered throughout the series were things that were beyond avant-garde for the time – posthypnotic puzzle command to keep the voices of 2000 years of warriors contained in his helmet occupied, heroes being tracked by a light dusting of radioactive gas, psychics preventing the public from recognizing the hero, 4th-dimensional energy, ultra-violent villains, super-hero groupies who make gifts of their, um, underwear, and the notion that superhero groups had deeper secrets than what the readers ever saw.

"We want to show things we've never seen before, like the JLA initiation, which is this whole Masonic-type of thing," Morrison said. "Aztek will learn the secret handshakes and passwords that heroes use so they don't run into trouble with shape-shifters and impersonators."

Aztek: The Later Years

Aztek's tenure with the JLA only lasted five brief issues, and the hero was given a convenient out in the aftermath of the 'Rock of Ages' storyline, when he confessed that due to his connections with Luthor he could compromise the League's security. At the time, rumors circulated that Aztek got the boot from the League due to the fact that he was a character whose own book was canceled and was too new to serve with the big guns. Either way, Aztek apparently returned to Vanity, to wait for Tezcatlipoca's return. Prior to his cancellation, Morrison and Millar had plans for the character, both within his own series and the JLA.

The series was to start building towards the confrontation with Tezcatlipoca's in mid-1997, after Aztek discovers that there's a grand conspiracy under riding the entire DC Universe, tied into his own upcoming battle. The conspiracy was to have far-reaching implications throughout the DCU, reaching all the way to the top levels of power (both Lex Luthor and Thomas Wayne had connections), and into other books as well. The battle with Tezcatlipoca was to take place in issue #24, and then.... um, well... they didn't have too much planned beyond that. After all, his motivation for fighting and existing was presumably going to be defeated in the battle.

Millar had a rather non-conformist idea on how to wrap up the Curt Falconer Aztek.

"Actually, issue #24 would be a logical point to kill him off," Millar said. "We think it might be cool that on the morning of the day after he defeats this ancient evil and saves the world, he'd get hit and killed by a car while he walked to work. Superheroes always have these grand deaths like, 'If I die, I die knowing I saved the multiverse!" We thought it would be great to have one die like a normal person, on the way home after getting a pint of milk. But then again, we might keep him around for a while after that. Who knows?"

Instead of buying it thanks to a careless driver though, Aztek's threat was realigned with the 'World War III' storyline, and retrofitted and clarified to be Mageddon. As such, Aztek appeared in the midst of the story, and, heroically, detonated his 4th-dimensional battery in issue #41, ultimately buying Superman time to escape from Mageddon's grasp. It was a crucial turn of events that allowed the JLA to win the day, as well as a perfect heroic end for Aztek, really. In the interviewing time since his debut which was supposed to be a return to the heroes Morrison and Millar were familiar with as kids, the 'big seven' had returned to the JLA, taking their place at the top of the hero hierarchy in the DCU, banishing grim and gritty in favor of big-screen heroics. Aztek's mission, both literal and figurative, had been completed.

So where should you go to find Aztek? If you didn't pick up the original issues, any reputable comic shop worth it's salt should have the back issues or available. In 2008 DC published a collected edition - JLA Presents: Aztek - but that's long out-of-print.

Given Morrison and Millar's post-Aztek work though, don't expect to find them in the discount bin unless you're really lucky. Grab 'em and enjoy, or if you bought them when they first came out, pull 'em out again and read it in one sitting. You'll be happy you did.

Aztek is available on most major digital platforms... but which one is the best? Check out our list of the best digital comics readers for Android and iOS devices.

Matt Brady was the co-founder and managing editor of Newsarama until 2008. Since then, he’s moved back to science and teaches high school physics and chemistry. He’s also written a handful of comics, as well as The Science of Rick and Morty from Simon and Shuster. With his wife, Shari, he started thescienceof.org, which blends pop culture with science as a means to increase student engagement and the public’s interest in science.