The secret origin of Joseph Illidge

From Brooklyn bodegas to breaking in at Milestone, Joseph Illidge shares his story

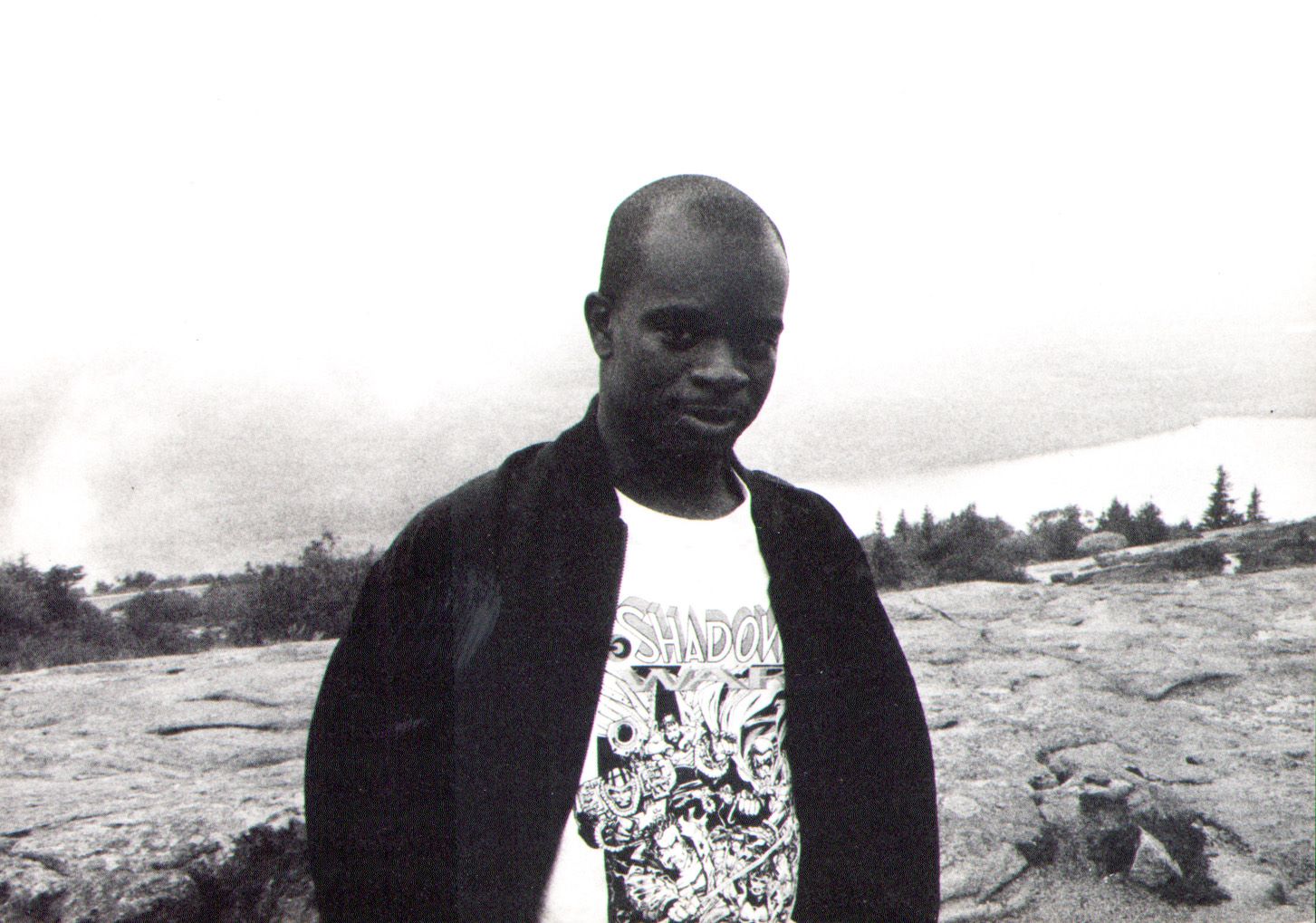

Joseph Illidge is one of the most well-rounded editors in comic books, having held major roles everywhere from DC to Valiant Entertainment, Lion Forge, Milestone Media, and now Heavy Metal.

As executive editor of Heavy Metal, he oversees not only the long-running namesake anthology magazine but is also part of an expansion of the company with several new imprints as it forges into a new era for the publisher.

But to see what Illidge is doing now, it's important to see how far he's come. His story includes '70s Brooklyn bodegas, Grant Morrison's idea of a "morphogenetic field," a chance meeting with Jimmy Palmiotti, and a hearty welcome from MIlestone Media in 1994.

As part of Newsarama's spotlight interview series 'The secret origin of...,' we spoke with Joseph Illidge to learn about his early days as a comics fan, and how that interest blossomed and was forged into a career in the comic book industry.

Newsarama: Joe, what's your first memory of comics?

Joseph Illidge: My first memory of comics would have to be the second grade. My mother and I had a tradition. Every Friday evening after work, she and I would go to the local newsstand. It was called TE-AMO, on the corners of Nostrand Avenue and Church Avenue in Brooklyn, New York. My mother would buy herself soap opera magazines and she would buy me comic books. Maybe three or four at a time.

I couldn't tell you what my first comic book was, but it was quite likely a DC Comics title. I enjoyed the tales of teams like Legion of Super-Heroes, Justice Society, and the Justice League. Stories of teamwork were appealing to me going back to those early days.

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

My father, God rest his soul, was also a buyer of comic books, but whereas I read superhero stories, his favorites were the war stories of Sgt. Rock, Deathlok, The Demolisher, and Scalphunter.

Now that I think about it, I bet my father's influence on going off the superhero path is what led me to start reading Master of Kung-Fu years later. That series by Marvel was like nothing I had ever seen. The art was so realistic and sophisticated, and the coloring was surreal.

Nrama: As a kid, how did you store your comics?

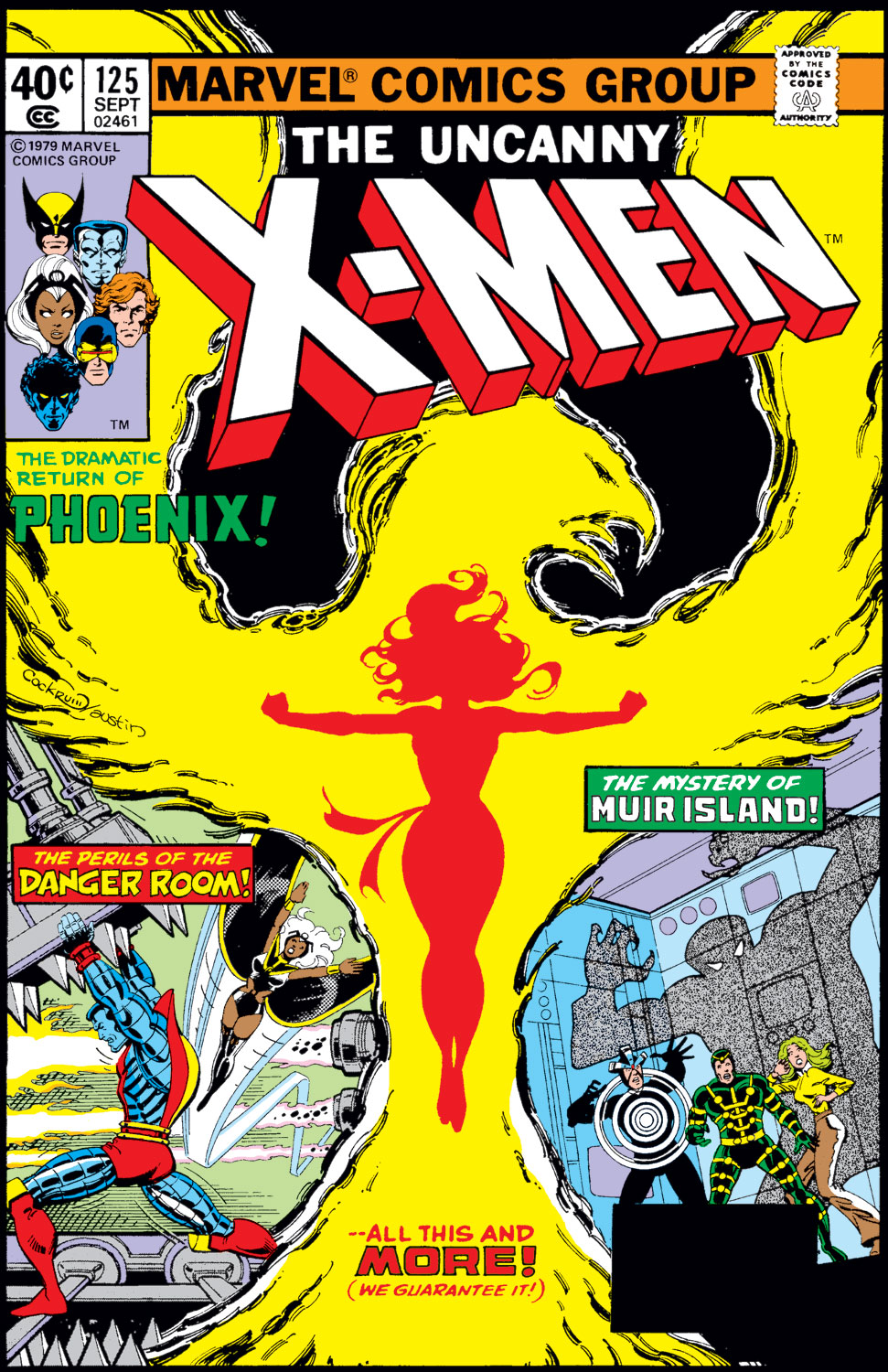

Illidge: My collection growing up was superheroes through and through, and when I was in the fourth grade, my aunt from the Bahamas introduced me to Uncanny X-Men, so that was the turning point at which I went from a DC Comics fan to a Marvel Comics fan.

My collection was X-Men, Avengers, Spider-Man, Master of Kung-Fu, Power Man and Iron Fist, and Legion of Super-Heroes, for the most part.

I stored them terribly, to be honest. Stacks on shelves, in a corner of the bedroom. It wasn't until my mother took me to Flatbush Comics and Cards as a kid that I realized comic books had monetary value as collectors' items and were stored in plastic bags with backing boards. From that point on, I stored most of my comic books in bags and boards, but they still went on shelves, as I wasn't ready for long comic book storage boxes yet.

As you can see, my mother is the primary person to blame for my career in this crazy business, by which I mean her support of my geekness was instrumental in my life path.

Nrama: At what age did you realize you wanted to make comics, Joe?

lllidge: I would have to say when I turned 14 years old, so that was the tenth grade for me as a student of New York City's High School of Art and Design. A handful of my friends were amazing artists and would create drawings of their characters. We would all discuss the backstories and mythologies for our ideas on a weekly basis.

Nrama: I might've been better asking this sooner, but when did you first realize how comics were made on a basic level? As in there's people doing it, not some monolithic entity?

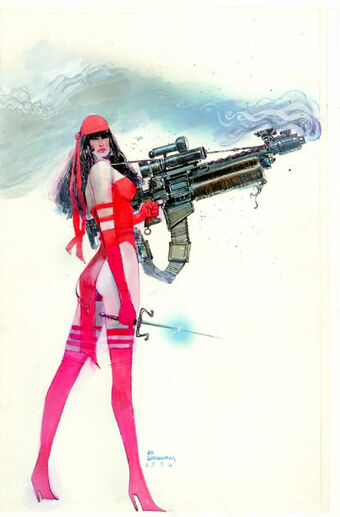

Illidge: When I was a student at A&D, as we all affectionately called Art and Design, a guy named Mark Matos arranged for a group of us to go on a tour of Marvel Comics. That day, walking through the offices, seeing an original painted page by Bill Sienkiewicz for a series that would be published a few years later called Elektra: Assassin, changed my perspective on comics.

Before that, sure, I knew people made the books, and the works of geniuses like Marv Wolfman, George Perez, Chris Claremont, Ron Wilson, Glynis Oliver, their works helped me survive the adolescent years. When I visited Marvel Comics, a more tangible understanding of the creation of comic books became crystal clear, as well as the business people behind the scenes.

Nrama: So what were the first comics you made?

Illidge: My friend, Caesar Antomattei, and I made a 22-page comic book about a married superhero couple. I wrote the script on loose-leaf paper, and Caesar did the black and white art, the lettering on the board, and a painted illustration that made the front and back cover.

I live with the eternal optimism that one day Caesar and I will make an updated version of that story and those characters, so forgive me if I stay hush-hush on the details. After all, I still have all of the original pages on bristol board downstairs in my basement.

Nrama: Was there a point where you feel you made real progress in skill level as a comic creator? If so, when was that?

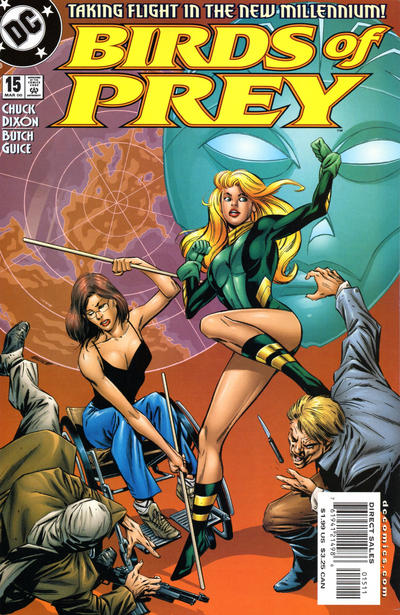

Illidge: From an editorial perspective, since I would really dive into writing comic books and graphic novels much later, I made a leap as an editor in the year 2000 when I took over the editorial reigns of DC Comics' Birds of Prey series from the founding editor and co-creator Jordan B. Gorfinkel.

The book had a spirit, a feel, and a diehard fan base, so I really leaned into the series, understanding what made it garner such affection and loyalty from the readers, and thought about how to maintain the quintessential nature of Birds of Prey while guiding the series forward.

Bringing artist Butch Guice on board was the final element in the evolution of the series, because we were taking the high-stakes, globe-spanning adventures and friendship of Black Canary and Oracle and getting down with the get down in terms of sending them at breakneck speed toward inevitable confrontations, with their enemies and their fears.

Nrama: Let's get back to your early days. From 1987 to 1990 you attended the School of Visual Arts in New York City, ending with a BFA in art, literature, and psychology. What was the comics side of your life then?

Illidge: SVA had a library, and it was there where I would discover the trade paperback collection format.

I was a big purchaser of comic books, but finding the collected editions of Frank Miller's Ronin; Watchmen by Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and crew; and Batman: The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller and Lynn Varley was another life-changing experience.

That's when I viewed these stories I loved as books, sitting on the shelves in a place that housed the works of Alex Haley, Samuel Delany, and C.S. Lewis.

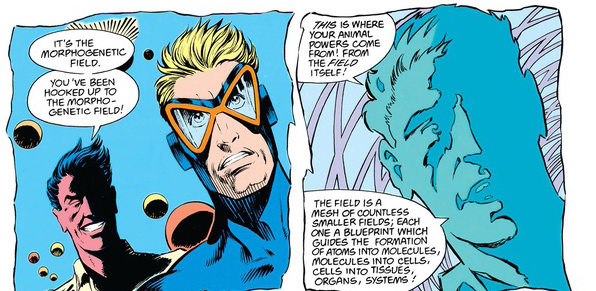

During my last year at SVA, when I would hang out in the cafeteria between and after classes in the geek corner (yes, there were territories with invisible borders), I met a girl named Lori. She told me about a writer named Grant Morrison, and the ideas he put forth in his work about Animal Man and something called a "morphogenetic field," within which lied the ability of the quintessential form of animals.

I found that intriguing, so after a long stretch of not really going to comic book stores, I went to Forbidden Planet. In those days, it was on the corner of Broadway and 12th Street, across the street from the Strand. So I went to Forbidden, picked up a few issues of Animal Man, along with an issue or two of Doom Patrol with stunning painted covers by Simon Bisley.

Aaaaaaand I was hooked on monthly comic books again. I became an avid reader of anything Grant Morrison wrote, while also getting my first taste of William Gibson's work with Neuromancer.

Nrama: I take it from the art school background you might have had some inclination to draw comics. Is that the case? If so, can you tell us more about that desire?

Illidge: Definitely. I was one of those kids who grew up dreaming to draw comic books like John Byrne. I was never good enough to do that, and I was doing more writing while my friends were drawing. The work of John Byrne, George Perez, those two had such naturalistic styles that still lent themselves to the fantastic. That's what I wanted to do, but it wasn't in the cards for me. That wasn't my skill set, and I didn't have the passion for it.

The people I knew from back then and know now, the ones succeeding in their careers as comic book artists, their passion is admirable.

After college, I had a conversation with my friend Andre Kendall that opened my eyes wide to the reality that I could not be a successful visual artist, and I woke up the next morning deciding that the written word, the story, is where my future in comic books would be.

Various friends of mine from college, including DC Comics and Marvel artist Chris Batista (who had the best idea for a Captain Marvel Jr. story, to this day), encouraged me to think more about writing stories, based on our mutual love of Japanese anime and the 'Five Years Later' era of Legion of Super-Heroes by Keith Giffen, Tom and Mary Bierbaum, and crew.

Nrama: There's a four-year period between SVA and when I first have a record of you joining the comic industry, at Milestone. What were you doing in between there?

Illidge: I was working at an art and sign supply store called PK Supply in Brooklyn. During that time, I was generating pitches for an anthology series Marvel had in publication called Marvel Comics Presents. I can't remember all three ideas, but one of them had Namorita from the New Warriors talking someone out of committing suicide.

Two things happened during my time working at PK that changed my life.

I returned from the back of the store and one of my co-workers told me he just rang up this guy who worked in comics. I asked him who. He said "Jimmy Palmiotti." I ran out of the store and caught up to Jimmy, who didn't know me from Adam. Jimmy was generous with his time and listened to me babble about how I had been sending in pitches to Marvel and getting no response. He took my name and told me he would speak to the editor.

One month later, I got a letter from the editor with thoughtful critiques of all three of my pitches. He wouldn't buy any of them, but the fact that he took the time meant the world to me, and that Jimmy Palmiotti, someone whose name I'd seen in comic books and met only once, was a man of his word.

The other thing was that a comic book store called Bulletproof Comics opened up a block away from my workplace, so I became a regular customer in their second week of business and started my long-standing friendship with the store's owner, Hank Kwon.

During that time, the Vertigo imprint began and a comic book named Spawn premiered on the shelves. Superman died, and mutants had therapy sessions.

Comic books were changing and transforming and there was an excitement in the air. A guy named Jim Lee was taking X-Men to new heights, and a company called Image Comics became the example of meteoric success.

Nrama: This 'The secret origin of' interview series is about how you came to comics, so I'll get right to the door - how'd you learn of Milestone, and how'd you manage to be hired on as editor in 1994?

Illidge: I learned about Milestone by reading about them in Previews and Advance Comics, the catalogs for Diamond Distributors and Capital City Distribution, respectively. Milestone had articles/interviews in both, and one of the interviews had a phone number to call for an appointment to become an intern.

My friend Jason Scott Jones, who became the Color editor of Milestone, told me about his joining the company as an intern, as well.

After blowing my intern interview to hell and Jason sticking up for me, they gave me a shot in their internship program, and after three months of hard work doing things that were both fun and tedious, the Milestone owners offered me a part-time job as assistant to the president. I accepted, and the part-time job led to a full-time job in that role.

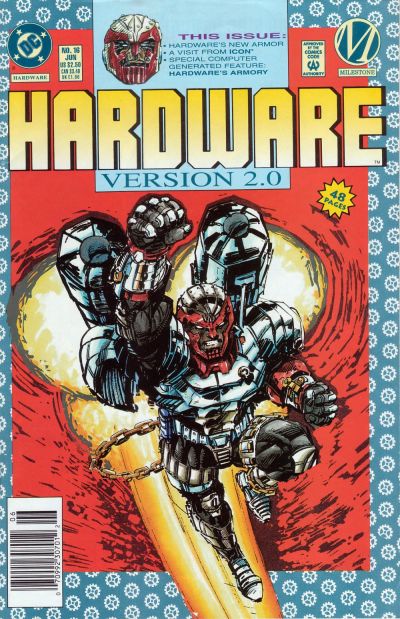

Once I had a thorough sense of the business side of Milestone, I let the founders know I wanted to move over to Editorial and begin working on the content. Dwayne McDuffie took me under his wing, and I started as an assistant editor working with him and editor Matt Wayne.

After about a year and a half, I was promoted to full editor and became the editor of the company's flagship series, Hardware. So I joined the Editorial department in 1994 and became full editor in 1995.

Nrama: What was comics like in 1994 for you, working at Milestone and living in NYC?

Illidge: 1994 was an exciting year in comics because you had Milestone, the first Black-owned comic book publisher to have a deal with a company like DC Comics, Image Comics, Valiant, Malibu Comics with their Ultraverse, and Chaos Comics. There was a real spirit of independent voices and creators getting their visions into the marketplace, at a time when comic books were selling in the millions of copies.

When I started working at Milestone, I lived in my hometown of Brooklyn, New York, and would eventually move to Jersey City, New Jersey for the first of three periods in my life living in that city.

1994 was Milestone's most vibrant year as a publisher, and as a magnet for Black creativity in the comic book space; luminaries and visitors ranged from Quincy Jones to Carl Lumbly of the MANTIS television series and later the animated Justice League shows to Vernon Reed from the rock band Living Colour.

It was a great time I wouldn't have missed for the world, and it's amazing to see how that era influenced comic books, popular culture, and the lives of two generations of people from its impact.

Nrama: Looking back on your path to comics, is there anything you'd tweak or change?

Illidge: Not a thing. Every career, every life, has peaks and valleys. If we went back and changed things to avoid the valleys, we wouldn't learn anything substantive about the world or about ourselves. We don't become better unless we live through some peril and make mistakes that force us to learn.

I've come to learn that events I considered bad times were actually windfalls in disguise. I dodged bullets I didn't realize existed until decades later. I've seen the true nature of people in the industry in both inspiring and revelatory ways.

Friendships were forged and experiences that many would have considered statistically impossible for a Black man born in the '60s were had, so I wouldn't change one single thing.

Nrama: If there was someone like you out there, wanting to break into comics, what would you tell them?

Illidge: If you're looking for a secure future, get a day job with benefits and make comics your side hustle. Comics are an amazing art form and the industry is full of many good people, but you need to go in with eyes wide open. At the point where you're ready for comics to be your full-time life, get a financial counselor stat.

Nrama: And 15 years from now, what is something you'd want to tell your future self not to forget - kinda like a message in a time capsule?

Illidge: "Keep being grateful, finish that book you're in the middle of, give your wife a hug, and call your mother."

Chris Arrant covered comic book news for Newsarama from 2003 to 2022 (and as editor/senior editor from 2015 to 2022) and has also written for USA Today, Life, Entertainment Weekly, Publisher's Weekly, Marvel Entertainment, TOKYOPOP, AdHouse Books, Cartoon Brew, Bleeding Cool, Comic Shop News, and CBR. He is the author of the book Modern: Masters Cliff Chiang, co-authored Art of Spider-Man Classic, and contributed to Dark Horse/Bedside Press' anthology Pros and (Comic) Cons. He has acted as a judge for the Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards, the Harvey Awards, and the Stan Lee Awards. Chris is a member of the American Library Association's Graphic Novel & Comics Round Table. (He/him)