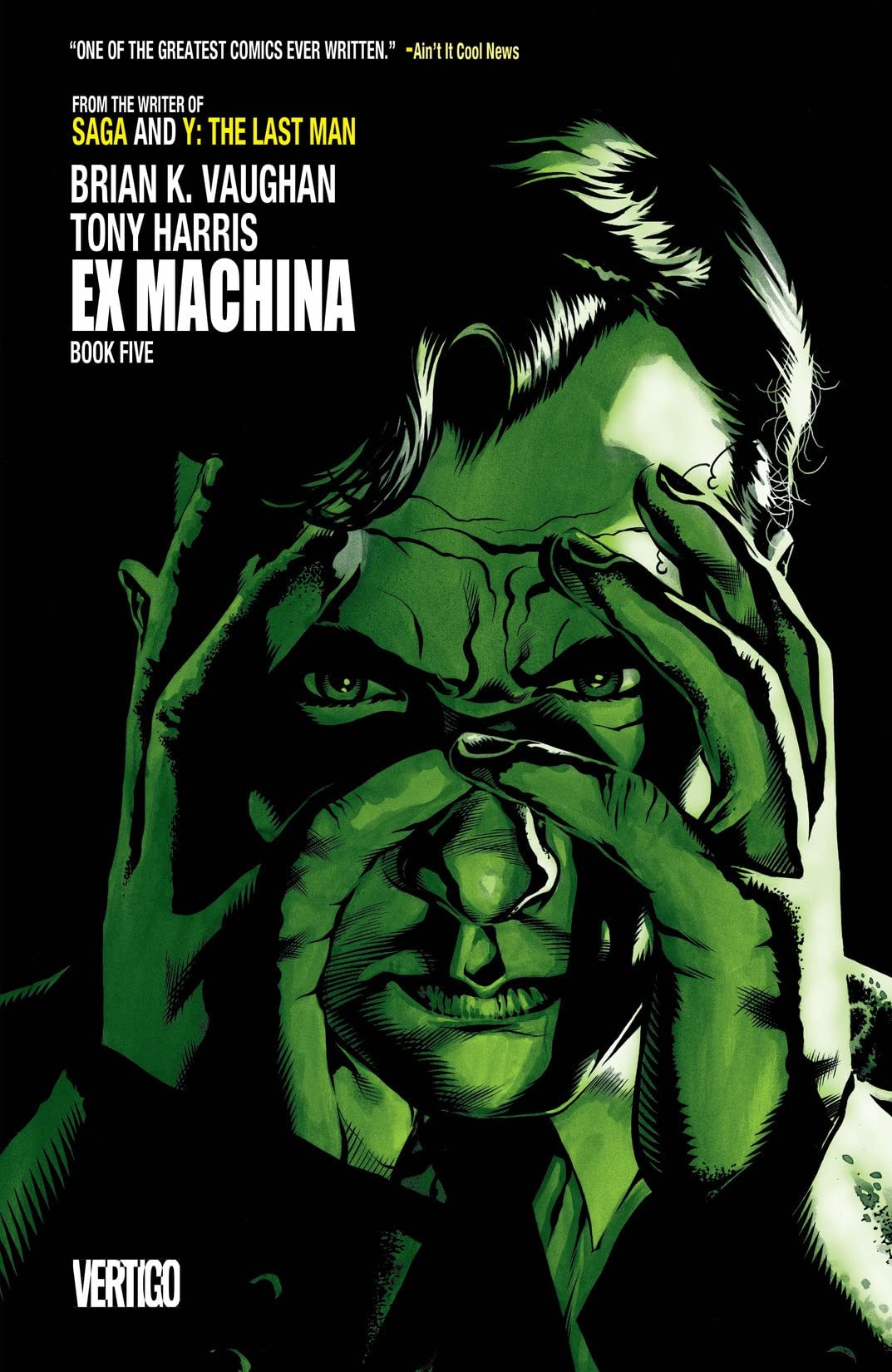

Best Shots review: Ex Machina hits you in the gut, and the heart

Looking back at Brian K. Vaughan and Tony Harris' seminal Ex Machina comic book series

What happens when the ordinary man gets an upgrade? What do you do with power and responsibility? And just because you can talk to machines, can any man - or superman - take on the endless cogs and gears that make up our world?

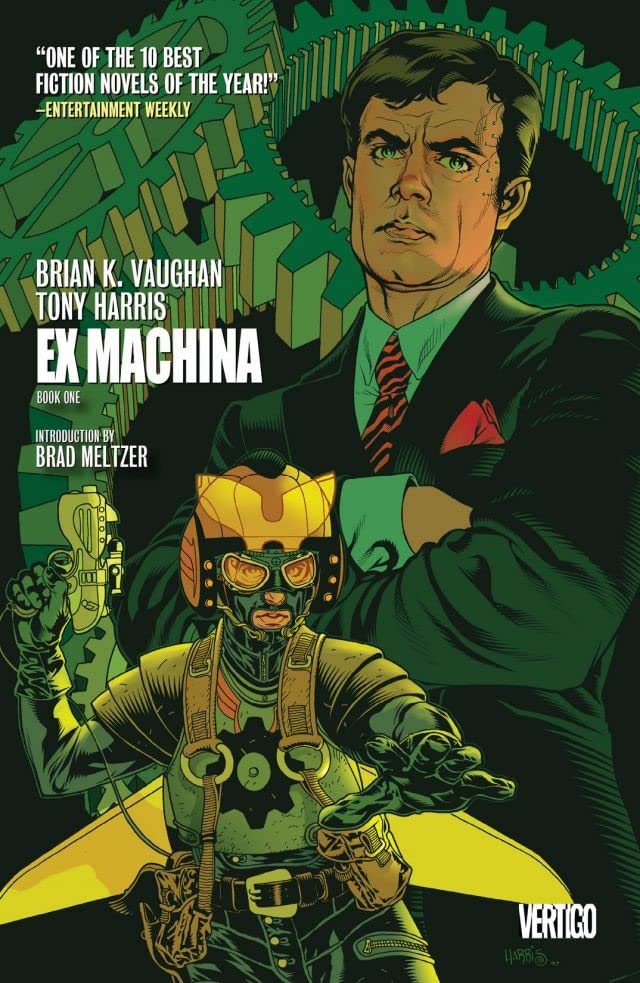

Written by Brian K. Vaughan

Art by Tony Harris, Tom Feister, JD Mettler, and Jim Clark (with guest art by Chris Sprouse, John Paul Leon, and Jim Lee)

Lettering by Jared K. Fletcher

Published by DC

'Rama Rating 8 out of 10

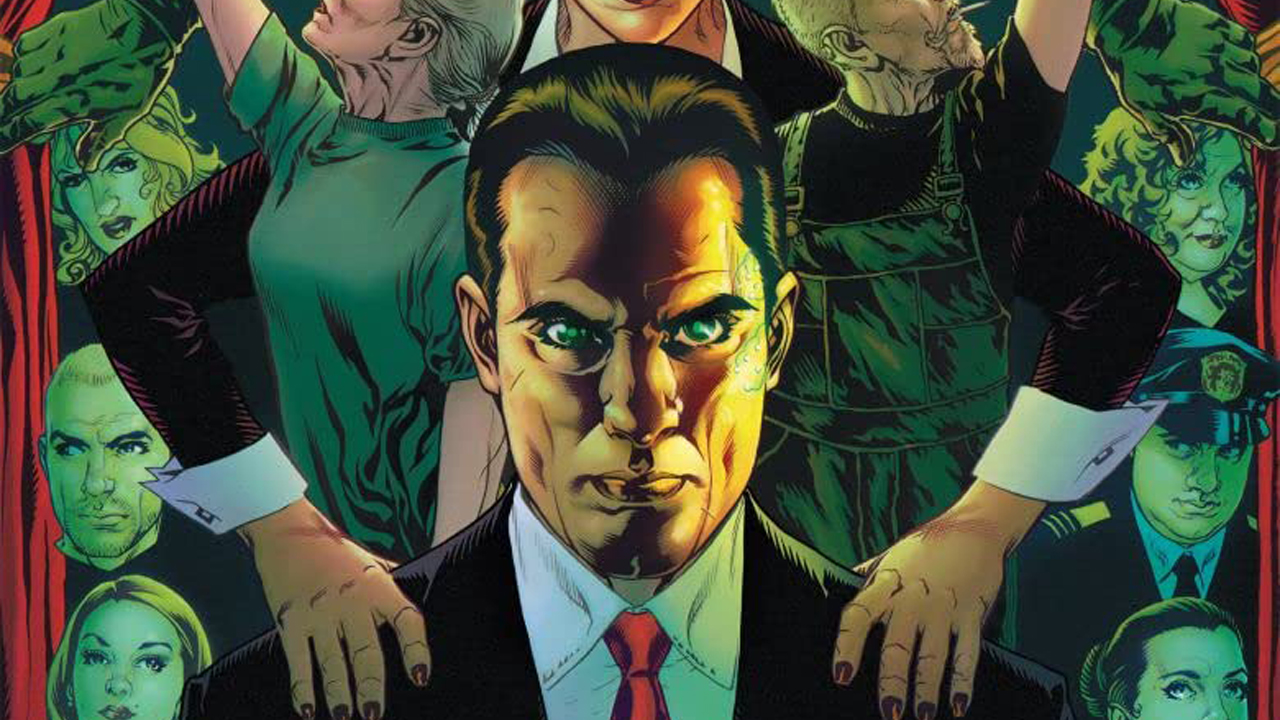

That's the question that is asked by Ex Machina, the political-superheroic drama by Brian K. Vaughan and Tony Harris. Spanning six years and more than 50 issues, the series was a massive labor for two creators at the top of their game. Seeing the high production values meshing with a pioneering premise, Ex Machina is a book that shouldn't just be experienced issue by issue - it's a storyline that deserves a global look.

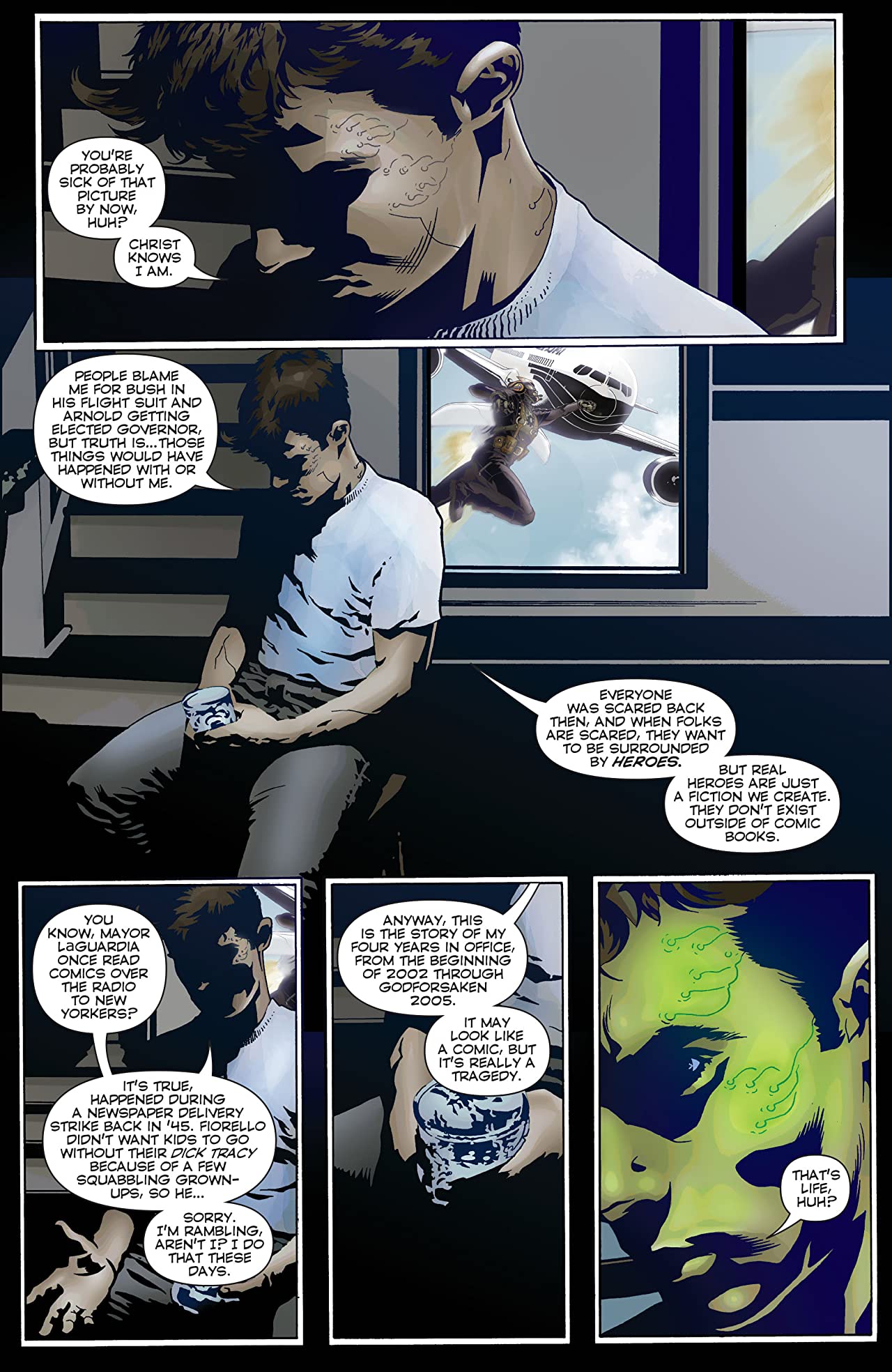

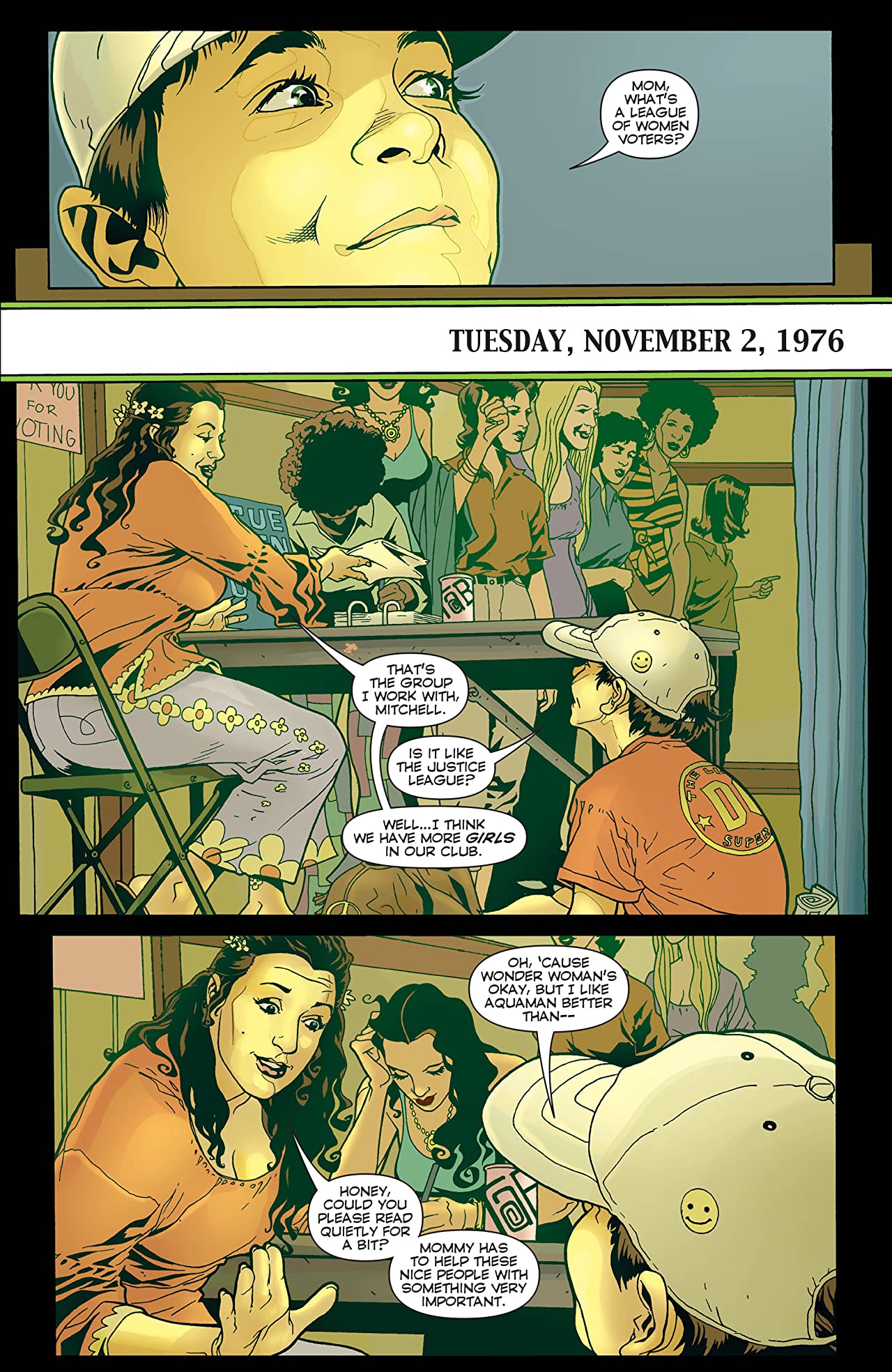

Make no bones about it - Ex Machina is built like a muscle car: all power and with a craftsman's tough. Just looking at the first issue, even years after it was printed, still has an impact, from the first splash page of the Great Machine to the eerie site of just World Trade Center tower. From those first 30 pages, Vaughan establishes the character of Mitchell Hundred, showcasing both his political present and his superheroic past - as well as a cast of vibrant supporting characters. Even though Hundred is just shallow enough that the reader can project themselves onto him, you get that Hundred can talk to machines - and you get that that's not a quick fix for every problem. You get Bradbury from the moment he says, "I'd bang that girl like a screen door." You get Wylie and Kremlin and the whole host of characters, as Vaughan and Harris set up a status quo so precise you could set your clock to it.

But the real machinery of this series is not Hundred's superhero powers, but the situations that he takes on as the mayor of New York City. When Vaughan is channeling his inner Aaron Sorkin, that's when he hits the height of his powers. He's clearly done his research, like during the former Great Machine's first "case" - a woman whose painting juxtaposing Lincoln and the N-word has turned into some political dynamite. Not only does he set up a seemingly intractable problem, but he manages to come up with a smart solution - not to mention some serious commentary on the nature of criticism - within the span of two pages. Even though not every political element of the series is a home run - the terrorism plot, which one would think would be the most resonant after 9/11, almost falls flat due to a lack of urgency, even as a special looking at the Ku Klux Klan and masked anonymity is the smartest single issue of the series - seeing Vaughan's flair with coming up with arguments and counterarguments is perhaps his greatest strength. While his tendency to drop factoid bombs can sometimes be a little obvious, Vaughan also makes you think.

And perhaps that's the most interesting side-effect of Ex Machina: that Vaughan has the wish-fulfillment properties of the superhero genre mashed on top of the contentious world of urban politics. Haven't you ever wondered, 'What if politicians did things differently?' This book took a stab at 'change' long before it became a political slogan: Seeing Hundred push for gay marriage in 2005 - at a time, in the real world, where only Massachusetts was the only state in the union to legalize it - is that sort of brash do-what-you-want-it-don't-hurt-me libertarianism that not only makes the comic pop off the page, but makes this story seem presciently ahead of its time.

And ultimately that level of wish-fulfillment mixes with national trauma when Vaughan takes us back to September 11th - it's frightening, the same terror that people had in offices and schools across the country. We all wanted a hero to stop the madness, and in this beautiful, horrifying, hauntingly-rendered universe, Brian K. Vaughan gives it to us.

Ex Machina #1 preview

Tony Harris, meanwhile, helps set the tone that the rest of the series rests upon. This is not hyperreality capes-and-tights indulgence but injected with some hard-and-fast reality. It's great to see the acting takes place in this book, whether it's Hundred making an obscene gesture when admonishing Bradbury on texting about their "deepthroat spot," or the look on an old friend's face when he's sitting homeless in a subway station, unable to tell the difference between fiction and reality.

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

"I... I used to be able to fly. I'm not making that up, am I?" he asks. "Could I really fly?"

This is some serious craftsmanship at work.

And to see his superhero stuff - well, there aren't many times where Hundred has his 'Big Damn Hero' moments, but the flashbacks to September 11th are as stunning as they are haunting. Seeing the Great Machine fly down the side of a collapsing building - shouting "please!" as he tries in vain to catch a woman who looks suspiciously like a young version of his mother - is absolutely heartbreaking, as colorist JD Mettler splashes the page with flecks of blood and rust.

But I think if this series has a weakness, it's this - it almost seems like, despite the strength of his high concept, Vaughan doesn't feel confident enough that it will succeed without some help. While the politics are always somewhere in the background, from the very get-go it seems Vaughan felt obligated to insert more pressing, more violent subplots - whether it's a suspected robot in the third arc, or a firefighter killer in the sixth - to artificially push the story faster. It almost feels like he's selling his premise (and his readers) a little short, but then again, action may just be his druthers.

Still, not only does the excess of action bits allow Harris to go crazy with some of the more visceral aspects of this series - you won't forget an image of a woman cutting her own hand off with a jagged stone, as Mettler turns the scene from a sick green to an overwhelming, otherworldly red - and it does bring Vaughan back to his old stand-by: the cliffhanger. Things rarely end up being what they appear to be, and while it keeps the reader wanting more, the overuse sometimes makes it feel like a crutch rather than a satisfying, organic storytelling tool. That said, when Vaughan does change things up - in particular, standalone issues focusing on perennial sidekick Bradbury, Commissioner Angotti, or even the authors themselves are less calling cards and more living, breathing mini-worlds - it's extremely refreshing, even if it reminds you how much more broadly this series could have gone.

Ultimately, the series does meander a bit in its third act. Vaughan manages to push the superheroic angle to its fullest with his introduction of the lovestruck costumed vandal known as Trouble. She really leaps off the page due to Harris' crazy-mirror-image design, as well as the twisted-yet-solid motivation by Vaughan. Yet once Trouble's fireworks come to a close, the engine that drives this book does begin to seize a bit. Chalk it up to having to build up a major foe for Mitch to handle, but, just like the dud that arch-villain Pherson brings to the table, Vaughan's late-game development of the mythology behind Mitch's transformation rings a bit hollow - even if you do get a fist-pumping thrill when you see how Harris portrays Mitch taking matters into his own hands.

Yet by the time the final arc rolls around, the series has taken on a whole new tone. This is the last hurrah, the funeral march, two trains racing toward inevitable destruction. To say that Vaughan gives us some surprises is putting it mildly - he completely gives you a paradigm shift. The game is changed irrevocably, and you see that the big success of this book isn't just the horror or guilt that Harris puts on his characters' faces. It's the structure.

This book is planned out like a machine, with a clear blueprint, a clear through-line from the very first issue all the way to its epic conclusion. Are there really heroes in the world of politics? And what is the morality of a man driven to save the world all by himself, so much so that he'd wear a mask? Tony Harris hits you in the gut, while BKV hits you in the heart.

Ex Machina is available now at comic book shops, book stores, and on digital platforms. Check out Newsarama's list of the best digital comics readers for Android and iOS devices.

[Editor's note: This review originally published in 2010.]

David is a former crime reporter turned comic book expert, and has transformed into a Ringo Award-winning writer of Savage Avengers, Spencer & Locke, Going to the Chapel, Grand Theft Astro, The O.Z., and Scout’s Honor. He also writes for Newsarama, and has worked for CBS, Netflix and Universal Studios too.