Rick Remender's Napalm Lullaby #1 dives into a dystopia that hits close to home

Rick Remender discusses the personal side of his new sci-fi comic Napalm Lullaby

Writer Rick Remender and his Death or Glory co-creator, artist Bengal, are reuniting for a dystopian sci-fi epic titled Napalm Lullaby. Behind the evocative title is a world where a cult dedicated to a new messiah hoards resources in domed cities while those outside struggle and starve.

If that sounds a little close to home given modern economic discourse, that's no accident, as Napalm Lullaby's layered sci-fi plot reflects many of Remender's own concerns for the real world through the lens of a future where some of humanity's worst fears are taken to their extremes.

Newsarama spoke to Remender about Napalm Lullaby #1 before its March 13 release, digging into what it's like to write about a dystopia built on the fears of your own modern world, and how to forge a lasting artistic partnership like the one he's built with Bengal.

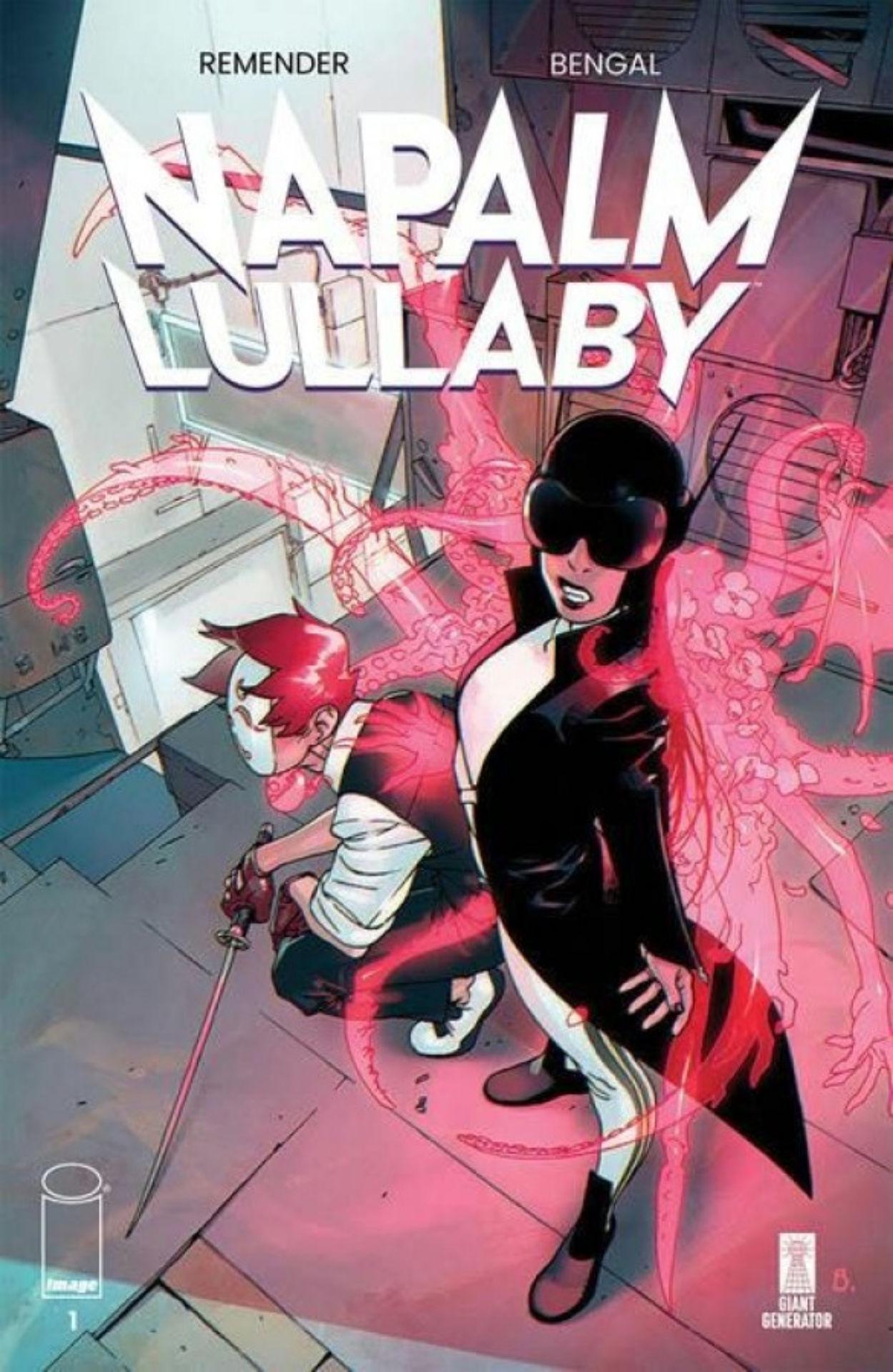

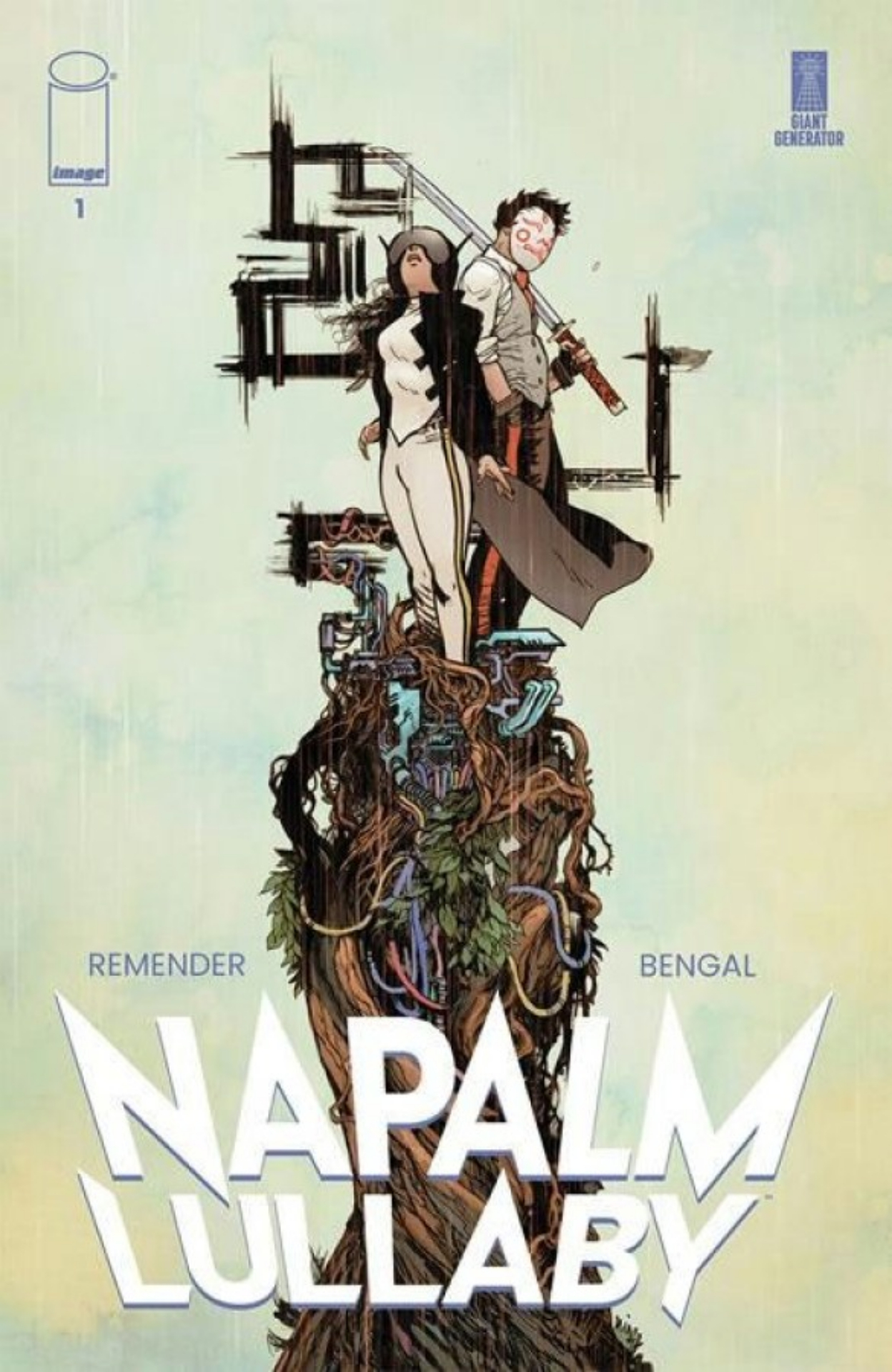

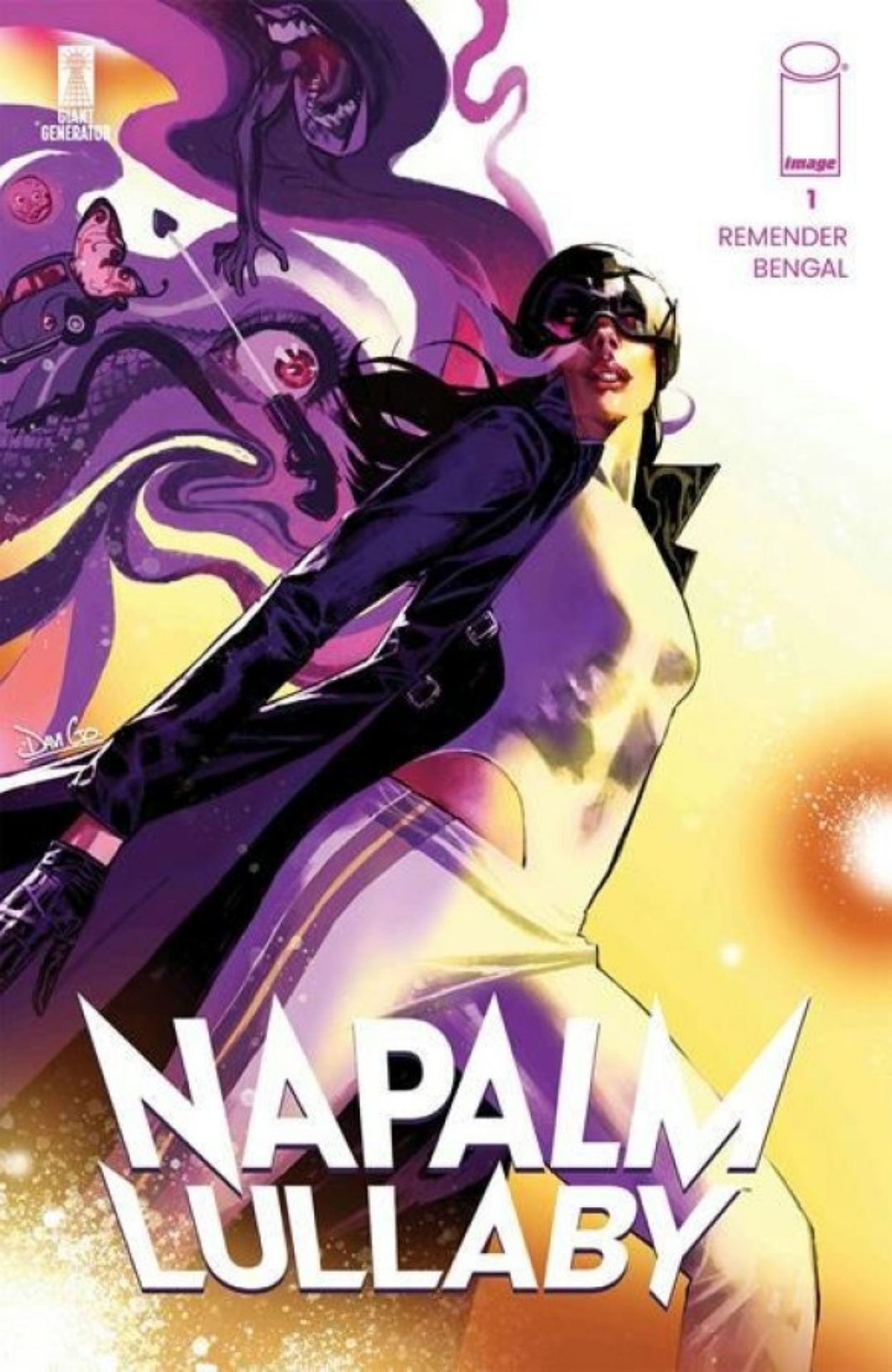

We've also got an early look at some pages and covers from Napalm Lullaby #1.

Newsarama: Rick, first off, I want to say, I really enjoyed Napalm Lullaby #1.

Rick Remender: It's a slow burn with a lot of mystery boxes, so that's nice to hear. You're one of the first five people who have read it. It's all a very new approach for me, to let the thing kind of breathe. Part of my earlier training, when I was at Marvel, was that you really had to sell everything all at once and get all the information across first thing.

I'm working on developing one of my older books into a television show right now which got sent to pilot, and I was looking at the old dialogue, and I was like, oh, I was still writing as if the first issue had to tell you everything. It really was an interesting experience, cause I've moved so far away from that. I now prefer a sort of airy mystery where you're hopefully brought in by the visuals and the interesting hook - but I'm not gonna give you too much information for a while.

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

The world building was interesting, it felt very organic. Something that I find interesting is the way this story dives right into themes that feel very relevant in our real world, through a very dystopian lens. What made Napalm Lullaby feel like the right book for right now?

Well, it grew out of a number of things that I had been developing for a long time. I keep a morgue of ideas that I keep returning to. At this point it's 7 million pages [laughs]. So I go through there and I look for things that get me excited. Sometimes it's an idea I burped up, you know, in 2010, that will mix with an idea from today.

And I'll find a way to kind of do what I'm always looking for at the beginning, which is something that I desperately want to say about my personal life that I've experienced, that I want to write about; something that I am observing in reality, or seeing in the world in the greater sort of society we live in; and then something really visual and interesting.

So what I had originally written on the pitch for Napalm Lullaby, it was originally called The Magnificent Leader. It was a story about if some kind of kooky cult, like a Jim Jones type cult, got their hands on the next messiah baby. And it was an interesting idea, it existed in my morgue for a while. Bengal and I had even started on it before our other book Death or Glory, because it was a little more exciting to me at that time to talk about the erosion of the American working class.

But then we circled back around to this because the hook that really hit me was the idea of moral authority, and the idea that we're now seeing this moral authority come from political spectrums, religious spectrums - everybody's got a moral authority, and you better do what they say, and you better get in line.

I loved that, because it plugged into this idea so well, that one of these so-called moral authorities had the power to impose that on the world. And that would be something that's an interesting stage on which to tell a story. I couldn't get my head around it until I said, oh, well, then we time jump into the future, and we're going to deal with a couple of this messiah's bastard children who were supposed to have been killed when they were born, but weren't, and now they have some powers of their own. And now they're going to set out to rectify or fix the world they were born into.

My kids are Gen Z, and they'll talk about climate change. And I'll realize, you know, the things that Gen X were screaming about that no one would listen to - primarily climate change and nuclear armageddon - I see now in my kids the fear of this happening to them. And so, then the story became very relevant to me, and I realized, OK, that's worth doing.

What's it like writing about a dystopian future that stems pretty directly from a world much like ours while also watching some of those seeds of dystopia actually being planted all around us?

Well, it's taking this sort of moral authority, where the internet has allowed every voice to create their version of a moral authority, and mixing it with the fear of economic inequality. You know, throughout my years as a punk rock kid, reading about this throughout my life, it's this widening gap. And you cannot have a civilization exist, it doesn't work, when all of the money is held by the one percent, which has now become sort of a trite idea, this notion.

But when income inequality becomes a gap this wide, you start getting - there's a lot of places in America I used to take my family on road trips, where I used to pull into a McDonald's or something, and now that place is falling apart. You're seeing America in decline in between cities in a pretty serious way.

And that's a big part of this. In the world of Napalm Lullaby, the Magnificent Leader and his cult have these beautiful domed cities, and inside are crystal cathedrals, clean air, water, food, shopping, delivery services, all the things you can imagine. But in order to gain entrance, you have to swear fealty and you have to absorb the dictates of the moral authority, and ultimate give yourself over to this thing in order to be part of that upper class, while the rest of the world lives in shanties around the cities.

And again, it's those three things: the world that I live in, something personal, and something that's visual. This ticks off all of those. My mother's family is very religious, and I was always the black sheep because I couldn't buy into any of it. I think Gen X has a real anti-authoritarian streak that can be a positive and it can be a negative. And I think when it comes to moral authority, I'm very hesitant to absorb anybody dictating anything to me.

I can absorb ideas, I can intellectually have debates, I can think them through, I can come to my own conclusions. But it leaves you almost adrift and homeless. And being adrift and homeless, intellectually as a writer, I think is good, because it separates you a little bit from the superb society, and enables you to take a loot at it from an outside perspective, which is a lot of what my science fiction does.

I want to ask about your working relationship with Bengal. His art is just so fantastic, and it feels totally seamless with the script. How do you go about developing that strong of a relationship with an artist? Does your own background as an artist come into play?

Sure. I mean look, I'm a great art director, because, you know, I'm an artist, I know what can go on a panel, I can help design the logos, I can help design the characters. I have a hand in all this stuff. All the Giant Generator books have my stamp on them as well as the vision and the voice of the artists. And I always approach that in a sort of collaborative way.

Not all of those things lead to long term collaborations. That's just sort of a chemical mix. So Bengal and I just get along. We just like talking stories. I'll pitch him things and he gets excited, and he can't wait to draw it. That's all you're looking for.

I was an animation instructor, and a teacher of sequential art at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco for a number of years, and a student of mine who later became one of my best friends who went on to become the art director at Bungie making Destiny and Marathon, he gave me one of Bengal's art books. This was in 2003, 2004. And to me, I was like, this is genius. So eventually I reached out to him and had a conversation with him about working together.

All you can do is engage, make a deal where it's a total collaborative situation where the ownership is 50/50, and everybody has a say. The future of the property can be determined by our chemistry, how we get along, and how we run the business. I think having that power and running things in a kind of punk rock fashion doesn't always suit me. It can make business difficult.

But when it does work, and you have a partnership like this, it works beautifully. It's why we get into comic books, to work with a really talented and kind-hearted and smart person, and spend years of your life telling a small piece of the population a story you care about.

Read the best horror comics of all time.

I've been Newsarama's resident Marvel Comics expert and general comic book historian since 2011. I've also been the on-site reporter at most major comic conventions such as Comic-Con International: San Diego, New York Comic Con, and C2E2. Outside of comic journalism, I am the artist of many weird pictures, and the guitarist of many heavy riffs. (They/Them)