Pushing the boundaries of common sense reveals Hitman’s true depth. Time for the rubber duck challenge

From the hands-on fibre wire to the long-range sniper rifle and everything in between, a life of assassination is a playground filled with deadly toys. Even something as basic as a screwdriver serves multiple purposes, as a diversion, a means to rig a trap or simply as a substitute for a dagger. There are so many options, but today I just want to know one thing: how far can I get using only an exploding rubber duck?

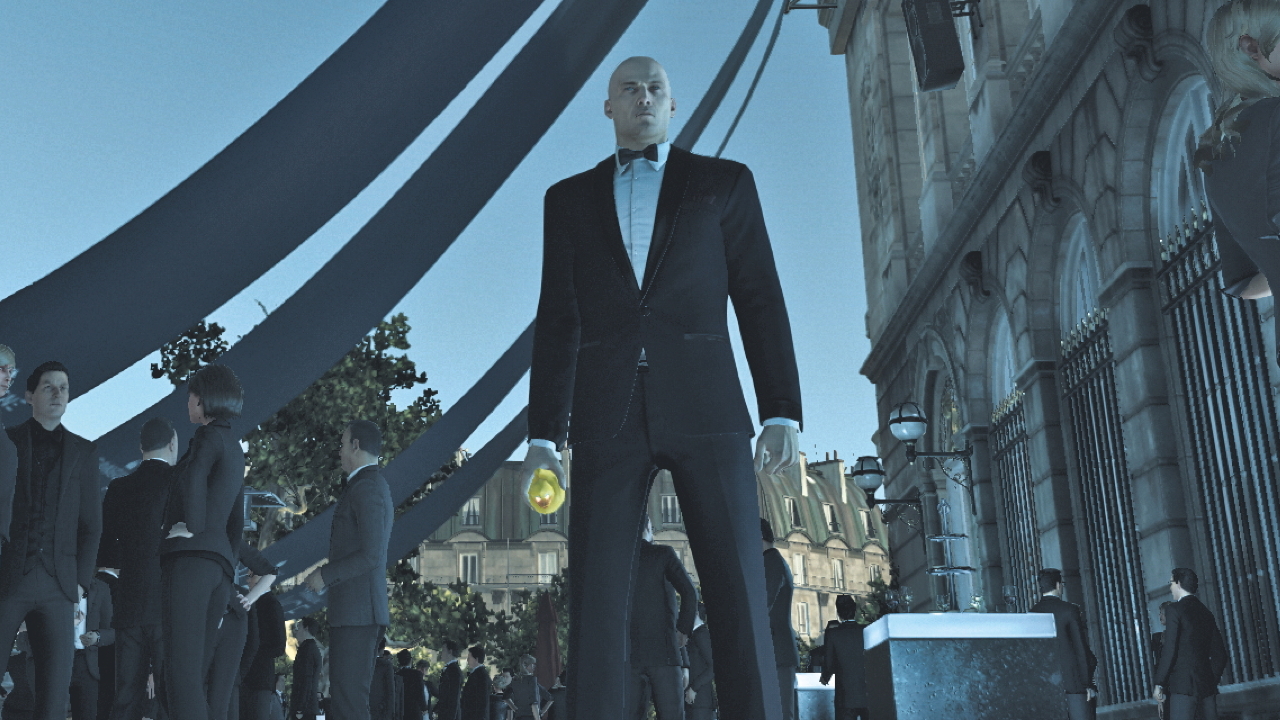

When I first try it in Hitman’s Paris level, I’m reminded of how thoroughly the game has been tested, tweaked, revised and patched since release. I could have sworn that interesting items would be investigated by the nearest character, even if he was a protected target, but if that was ever true in an earlier version it doesn’t work anymore. Unaware of this flaw in my plan, I stroll into the mansion, brazenly brandishing my duck, and find a space in the crowd. A spotlight picks out Viktor Novikov as he makes his grand entrance and I quietly lob the duck onto the staircase ahead of him.

I’d intended for him to pick it up and carry it around, which is surely not an unreasonable expectation. I was then going to sneak upstairs to find Dalia Margolis and do the predefined hit where I shove her off a balcony and she lands right on top of Novikov. My masterstroke for a killer video clip would have been to set off the duckbomb as she fell, killing them both and, with a little luck, blasting her skyward from whence she came.

Instead, Novikov immediately senses danger. He pauses and sends a bodyguard to investigate, at which point I start attracting attention from other parts of the room. To distract them I set off the bomb, which actually does kill Novikov, along with his bodyguard and a handful of bystanders. Panic ensues as the crowd rushes for the exit and I leave the building among them. Then I remember that I need to take out Dalia, who is now locked in her safe room. Back to the drawing board I go.

Levels where it’s possible to isolate the main character are easier. In Thailand, Jordan Cross rehearses in a recording booth with a small bin in the corner. It seems like the perfect spot, and sure enough the duck can be completely concealed in the bin, so I hide it and wait for Jordan to show up. He arrives on schedule, and I stand right outside the window to ensure that the last thing he’ll see is me.

This is when I discover that either the bins in Thailand are massively over-engineered or a small rubber duck can’t really hold enough C4 to form a room-clearing bomb. It makes a big enough noise to break the window but Jordan Cross is pretty much unscathed, and the last thing I see as his security men cut me down is the surprised look on his face beneath that ridiculous man-bun. Still, this is my Groundhog Day and I have the last laugh when I reload my save and plant the duck on the floor next to his microphone stand. He reaches down to grab it, and I can only hope that the guards who came to bag him up afterwards brought a mop and bucket.

Colorado proves to be a harder assignment, due to there being four targets and just two rubber ducks. Perhaps there’s a way to get them at the precise moment their paths cross, but the bath toy’s explosive power is clearly limited, and it’s extremely hard to lay an ambush because of its high visibility and irresistible nature. Rubber ducks are like catnip in Hitman, which is unfortunate when dealing with the proximity-triggered variety.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

In the end I settle for shooting pretty much everyone in the level, which is a super-cheap fallback technique that always delivers. With all four targets completely unguarded, all that’s left is to knock them out, pile them up and throw in the duck. In Hokkaido, the challenge of performing a fatal quack attack on Erich Soders is compounded by the fact that he’s right in the middle of heart transplant surgery. Yes, he’s a bit defenceless at this moment, but how am I supposed to casually place a bright red squeezy toy (with glowing eyes) on the operating table, given that it’s the single most attractive object in the world of Hitman? Even if I could put it there, one of the doctors, nurses or guards in attendance would surely run off with it.

Having Soders grab it himself is probably out of the question, what with the general anaesthetic and all that, so I’m reduced to knocking out a nurse in an anteroom, lobbing the duck through the open door and running for the exit as I trigger it. Not exactly elegant, but explosive assassinations are rarely ever subtle.

While it is almost certainly possible to kill every target in the game using rubber ducks, as long as you bring a backup weapon to take care of the heat you’ll attract while doing so, why would anybody want to? The answer lies at the heart of what I love about Hitman, namely that there’s no right or wrong way to do it. Everything IO Interactive has added to set you up with a perfect hit is optional, and no matter how bad a mess you make of it you’ll never be told what to do.

There’s no special person who needs protecting, no ‘game over’ for killing too many civilians. You’ll never be forced to stay within a particular area and you won’t have to go back to a checkpoint if you get spotted. Even the most liberal open-world games will make you replay a mission for failing some of those conditions, which makes Hitman all the more remarkable when you consider what a traditionally rigid genre it comes from. However hard you try, you can’t break it. Hitman is the Tonka truck of stealth.

There are rules, of course, and exploiting the fact that Hitman is clearly and unashamedly a videogame is part of the fun. Anyone who’s whiled away a few hours replaying a mission to unlock its numerous opportunities and challenges will probably have spent a good chunk of that time trying to lure troublesome characters to a particular spot. There are various approaches. Guards can be shifted out of their routine by dropping contraband.Enforcers can be nudged into a halfway alert state by hanging around in their line of sight just long enough to get them to notice you.

Throwing a coin is the method introduced in the tutorial, and this can be exploited to separate a single character from a group. By dropping coins in precise locations you can even determine which way the character will turn when he comes to investigate and where he’ll stand when he gets there. Finding these little windows of opportunity can make for some fiendish challenges when you come to create custom contracts.

I do wonder how many people are actually delving this deeply into Hitman. Most of the Achievements beyond the third or fourth episode, even the easiest ones, are currently the diamond-encrusted ‘rare’ type. At the time of writing, only four per cent of players had unlocked the Achievement for smuggling an item into the splendid Hokkaido level, which is almost a prerequisite of finishing it more than once. How anyone could get to the end of that level, and consider the game ‘finished’ is beyond me.

I think that ignoring the obvious and just trying to assassinate targets in improbable ways is actually the best way of discovering Hitman’s endless possibilities. Push it to the limit, embrace the chaos and stay away from the restart button – finding a way out is part of the fun. It’s how I got hooked on the series in the first place, as many levels in the early games were extremely difficult to complete ‘properly’. As beautifully crafted as this new Hitman is, it’s comforting to know there’s no problem that can’t be fixed with a rubber duck or two.

This article originally appeared in Xbox: The Official Magazine. For more great Xbox coverage, you can subscribe here.

Martin Kitts is a veteran of the video game journalism field, having worked his way up through the ranks at N64 magazine and into its iterations as NGC and NGamer. Martin has contributed to countless other publications over the years, including GamesRadar+, GamesMaster, and Official Xbox Magazine.