History is a blind spot for video games - but it doesn't have to be

Thousands of people across the globe work tirelessly year after year on the Assassin's Creed series, crafting gorgeous and expansive digital representations of famous cities as they existed in history - Paris during the French Revolution, Italy during the Renaissance, and so on. These games offer a peek back into time that few games offer; a way to interact with the past in a tangible way that a history book or documentary can't even match.

But do they really? You might spend your time hopping over Colonial American rooftops and chatting with Benjamin Franklin or George Washington, but if you think about it, history in the Assassin's Creed series is mere window dressing for the centuries-spanning conspiracy that drives the narrative. Various historical dignitaries become mission dispensers, spouting a few lines and then sending you off on your way. The genius of Leonardo Da Vinci's inventions is relegated to a few moments where he crafts a new upgrade that makes stabbing people easier. The systemic issues of child labor in Victorian London amount to nothing more than a handful of rescue missions. There's a novelty to Assassin's Creed's approach to historical tourism but whatever references it makes to actual moments in history are tangential at best.

If you look back at the past few generations of video games, you'll notice that that Assassin's Creed isn't the only big-budget franchise that takes a surface-level approach to history. Call of Duty used to focus entirely on World War 2, and while it accurately recreated the weaponry of the era and various battles within, it rarely touched on the effects of that war on the people who lived in and around it, instead opting to focus on gung-ho action sequences and gallant movie heroics. And while Uncharted and Tomb Raider are filled with antique relics and tombs created by ancient civilizations, they're mostly there to get completely torn apart by our heroes as they combat evil mercenaries and mythical beasts. It's hardly National Geographic.

That's not to say historically accurate games don't exist - it's just that they tend to exist solely as PC strategy games, using history as a frame for player choice and interaction within a specific era. It's great that the Total War series lets you really dig into the militaristic aspects of each time period they place you in, and they do a great job at recreating some of history's most influential battles, but there's a whole side to history outside of war that these games tend to gloss over.

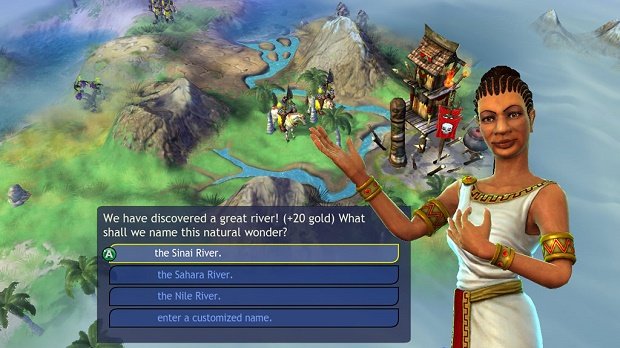

Civilization takes a similar approach but applies its gameplay to the full spectrum of human events. The turn-based game explores a wider range of topics, human achievements, and political entanglements, but it also ignores some of humanity's darker tendencies in favor of a more optimistic outlook. And while its world leaders represent famous people throughout history, they're generalized caricatures of the real thing - like how Gandhi's propensity for nuclear war became a series-long Easter egg after a bug turned the peace-loving leader into a warmonger in the first version of the game. Like Total War, it uses history as a way for you to interact with these defining moments on a broader sense, while a lot of the more intimate and finer details get lost in the translation.

History, it seems, is a blind spot for narrative-driven video games, but it doesn't have to be this way. Ironically, one of the best big-budget explorations of history happened in Freedom Cry, an expansion to the pirate action-adventure Assassin's Creed 4: Black Flag. In it, you play as Adewale, an ex-slave-turned-assassin who attempts to disrupt the Caribbean slave trade. Rather than raiding plantations for monetary gain like in Black Flag, Adewale does it to free slaves, to bring them onto his crew, and to get revenge on white plantation owners. But try as Adewale might, there's no end to slavery in sight, as every time he turns a corner, there's another captive to be found. The entire slave economy of the time is conveyed not only in the plot, but the very loop that forms the core of its gameplay, and it instills both a sense of duty and helplessness in the player - you want to save everyone, but you're only one man, working against a massive, unstoppable machine built out of perpetual misery.

What Freedom Cry does best is one of the things that is wholly unique to video games: allow the player to feel empathy for their character and the people around them by letting them directly interact with the world and its inhabitants. It's one thing to understand that slavery is bad, to know that black people have been historically treated like property, that the sale of human lives has formed the economy of our own country for hundreds of years of its history. It's another thing entirely to see that atrocity first hand, in a real place, in a real time in history, surrounded by real people; to be able to walk up to an outdoor slave auction, witness the trade of human lives for coin first hand, and to want so badly to do something about it. To know that while you won't be able to stop the cycle completely right now, you have the desire and the power to affect at least some small amount of change. And Freedom Cry is able to get that reaction from the player because it's smart enough to put the whole assassin/Templar/Piece of Eden nonsense as far into the background as it can.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

It's empathy that makes video games such a potent storytelling medium, and straight-laced historical fiction offers an opportunity for presenting that empathy in an honest, relatable way, without other details clashing with it and drowning it out like so much white noise. While games like Dragon Age: Origins and The Witcher may delve into racism and classism, their fantasy settings only look at these issues in broad strokes, like staring into a blurry mirror. In fact, these settings might even obfuscate the point further - since the world they represent isn't our own, it can be easy to dismiss them as pure fiction. Even Bioshock Infinite, as rooted in our own history as it is, is so concerned with its alternate history, its dimensional tears, its flying city, and its own convoluted mythology that whatever message it was originally trying to tell gets completely ignored by the second act.

Historical fiction offers an insight into who we were as a society and how far we've come, and making video games out of these moments feels like such a no-brainer. Games can be so much more than mindless entertainment or fun simply for fun's sake; they can instruct, inform, and build empathy, and do it without feeling like cheaply produced "edutainment". There are so many interesting events throughout human history, so many important achievements and dark patches that define our growth as a civilization, and it's surprising that big-budget games aren't doing more to explore them. We've got sci-fi and fantasy locked down pretty well - it's time for games to take an honest look at our past.