Best Shots Review: The ever-shifting dimensions of Fraction, Bá & Moon's Casanova

How being bad got good again

In a medium that encompasses concepts multiverses, Hypertime, and shifting timelines, perhaps the most difficult concept to navigate as a comic book author is the status quo. If your work stays on a singular idea for an extended period, the readers may start to get bored. However, if you shake things up and make too big of a change, readers will, at least initially complain that the change is too much, too quick. This is an issue that persists more when discussing issues released by Marvel and DC, however, it does apply to creator-owned and independent work as well, seen with the response from some to the second half of Scott Snyder and Sean Murphy’s The Wake. Comic books are largely a serialized medium where readers need to pay for the next installment, so there’s an added cost value to sudden changes – it’s not as simple as a plot twist at the end of an episode where the explanation is part of the package you’re already paying for.

Matt Fraction, Gabriel Bá and Fábio Moon, however, found a way to overcome this with their long-running series Casanova (released first at Image back in 2006, followed by a stay at Icon and then a return to Image in 2015) which is quite simple - always be doing something different to ensure that you, and the readers, never become comfortable with the series being purely one thing.

A dense and multi-layered narrative

Despite having run for more than ten years already, only 26 issues have been released. Intended to be seven volumes, each corresponding to one of the deadly sins, the series is currently in its fourth - with eight issues of an expected 16 already out - but there’s so much story and plot contained within the folds of each issue that the dense and multi-layered narrative, like Planetary, that it feels exponentially richer and textured the more it is considered.

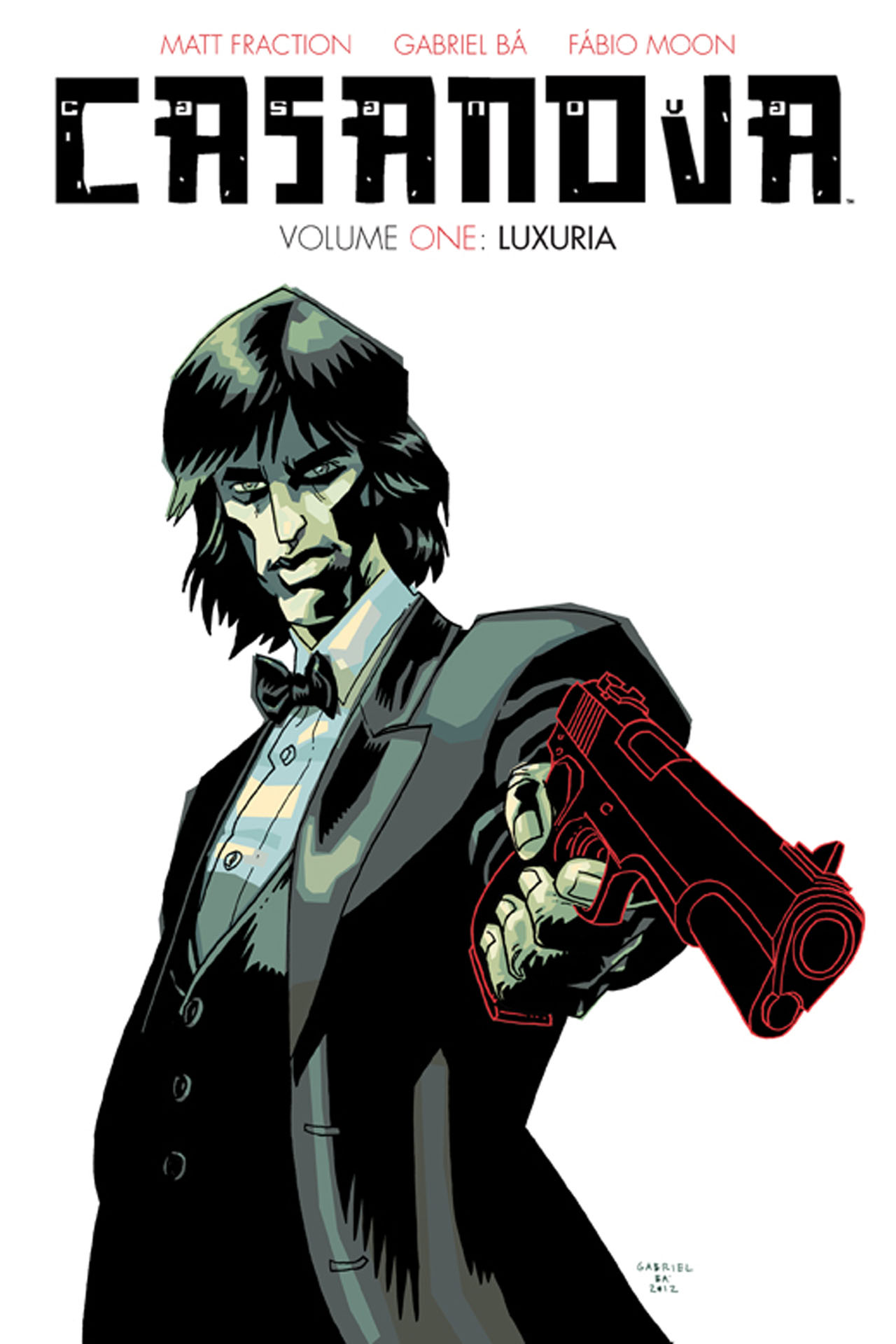

The series begins by by introducing Casanova Quinn, an infamous thief and playboy of Timeline 909. After he's pulled into an alternate timeline, so begins a game of inter-organization espionage between E.M.P.I.R.E and W.A.S.T.E. The leader of W.A.S.T.E., Newman Xeno, forces Quinn to become a double agent inside E.M.P.I.R.E. - who it just so happens is run by his Casanova's father.

Despite being an initial premise, it is more detailed than a logline or an elevator pitch and this information is part of a bombardment thrown at you in the first issue. There’s not really a moment to slow down and digest it all, but that pace is part of the fun.

The influences

If it’s not already clear from the acronyms used above, this series wears the Jim Steranko and S.H.I.E.L.D influences on its sleeve and when that item of clothing gets ripped off in the throes of passions, you’ll discover it also a tattoo that indicates a Howard Chaykin influence. In addition to these, the family dynamics are present from the opening sequence and inherently twisted from there, much like Christopher Priest’s current Deathstroke title at DC, but the further you get into the series, the more it’ll become clear that there’s a great deal more going under the hood when it comes to this aspect and every other that Casanova encompasses.

What nuance you first identify may depend on the person you are - one friend was drawn to the similarities and subversions of Michael Moorcock’s Jerry Cornelius stories - and in the case of myself, I came to realize that series was rooted, not only in the notion of change, but also the belief that whatever change you seek has to be for the better.

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

One such way is in the missions that Cass and other agents are sent on by the two organizations. Even when the aim of one is geopolitical destabilization, the reason for deciding to undertake this task is the belief that their world, be it at large or the more contained one they choose to acknowledge, will improve through a revolution being overthrown or the displacement of a leader from their position.

Following this thread up the chain of command brings us to Newman Xeno and his reason for stealing Cass from his timeline. The decision is rooted in nefarious thought but demonstrates that Xeno believes he will be able to reap the benefits, be it riches or power, even if he chooses to neglect the consideration of if his decision will be for the greater good of the timestream at large.

Who is Casanova Quinn?

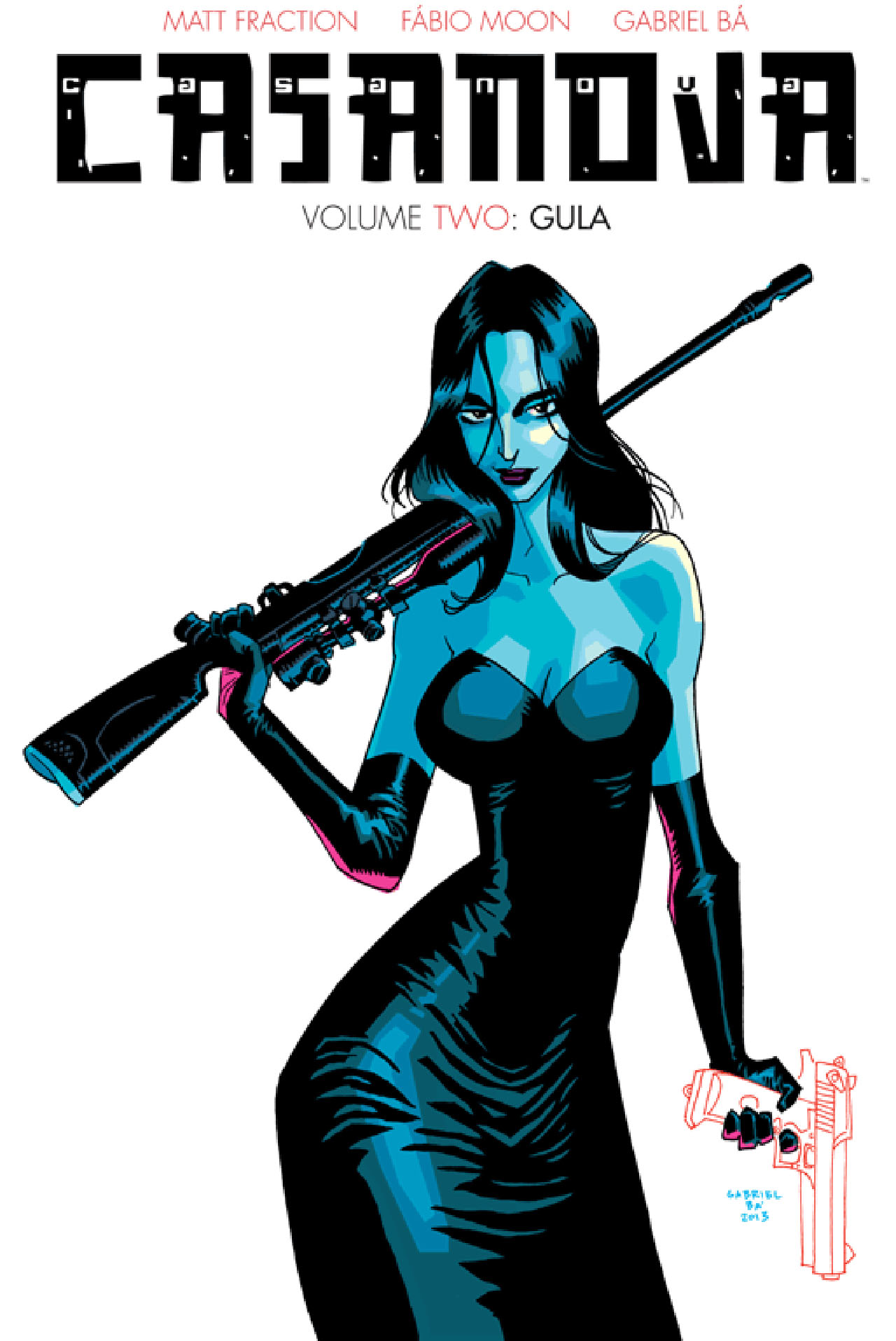

The subheading to Gula, the second volume, is ‘When is Casanova Quinn?,' and if I had to give Luxuria a subheading in this style, with my reading of the series in mind, it would be ‘Who is Casanova Quinn?’. Those first seven issues of this series see him being dragged from the timeline he knows, but it also means a second chance is gifted to him. Over the course of the arc, a gradual course correction can be seen in Cass, with the thinking that he can be better than he was in his original timeline, even if this doesn’t result in him becoming a character driven by altruism.

Much like Damon Lindelof and Tom Perrotta’s HBO series The Leftovers has shown, the key isn’t what we believe in but instead the fact we have a belief in something at all, and in some cases, this is a belief that things will work out.

Fraction gets personal in the backmatter

Upon Casanova’s return to Image, the creators released new hardcovers that not only contain the intently personal story, but also the extensive backmatter that’s a fundamental part of the series and adds to this feeling. As mentioned, the publication history of the series is extensive and so this backmatter runs across multiple years of Fraction’s life, collecting his reflections on the material, then and now, but also documents tragedies that befell his family. I don’t intend to provide an analysis or armchair diagnosis of these heart-breaking situations, but instead show that the way Fraction writes about them, whether in the actual text of the series, giving it an autobiographic tint, or the backmatter itself, shows that the series comes from someone who believed that, even when tragedy strikes, like a miscarriage, it’s possible to overcome them and come out on the other side as stronger.

The brothers

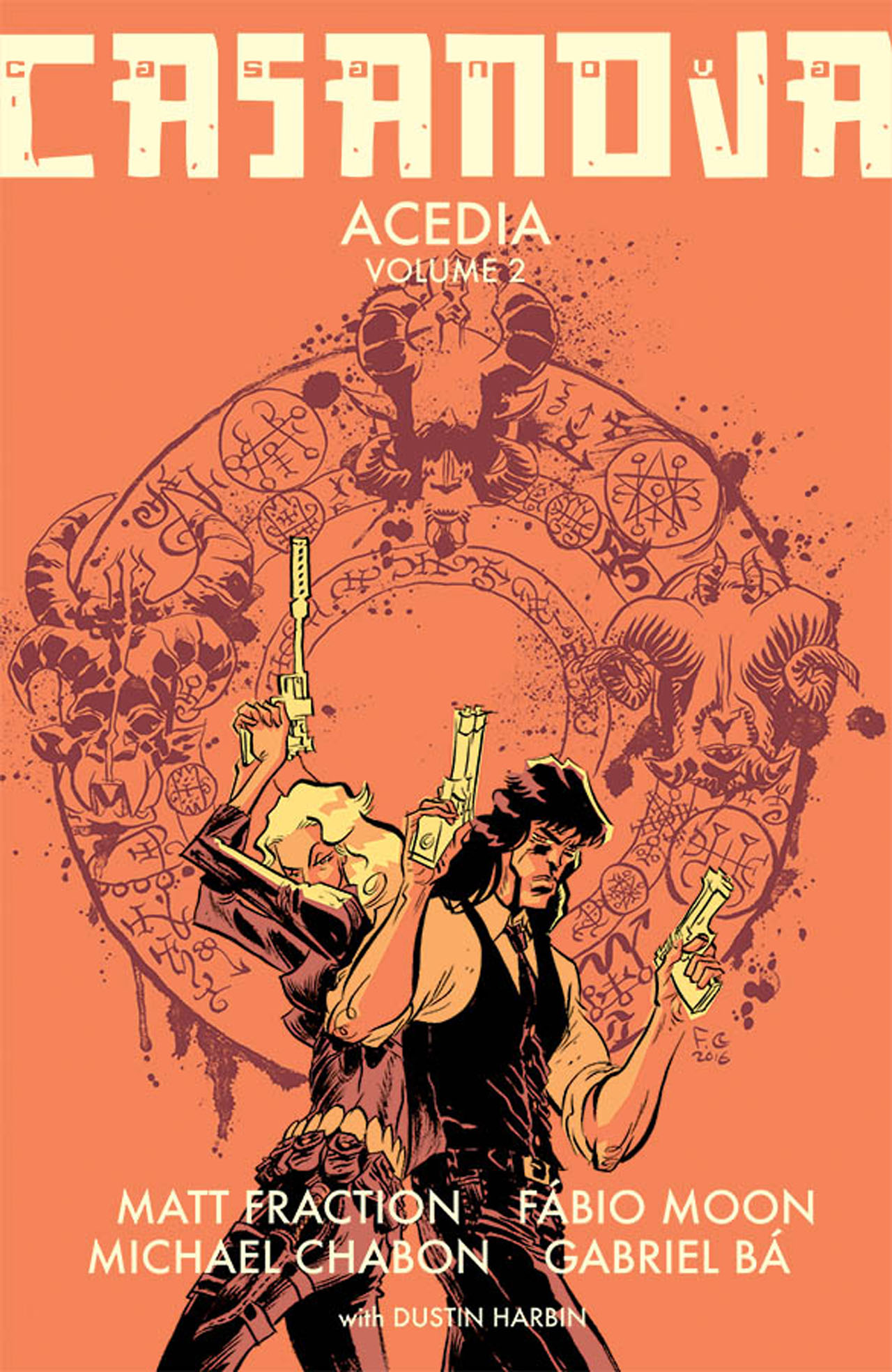

With this heightened autobiographical nature in mind, change becomes an intrinsic part of the book, revealing itself to be a formal component. Gabriel Bá and Fábio Moon have similar styles, but they trade off every arc allowing for a sense of cohesion between the albums, much like musicians who develop their sound without finding a completely new one. Moving from Luxuria to Gula, the series shifts from an eight-panel grid to a six-panel grid, and then Avaritia, the third volume, adopts the use of the occasional splash page in order to sell the sheer bombast of the arc. These could have been seen as risks for a series looking to maintain the initial audience that liked what the original Casanova #1 was, but these three examples also represent the belief that the book would only benefit from these changes to match the content and that the audience would be willing to go with it. At this point in the series’ publication, the peak example of this can be seen with the most recent volume, Acedia, which doesn’t merely shuffle the pieces around the board, but instead deposits the pieces on a new board, starts playing a new game, and asks you to learn how to play while the game’s in progress.

What do you think?

There’s more that demonstrates this core tenant of the book, and likely more that hasn’t occurred to me and won’t until the second half of the saga is in front of me. I could discuss Newman Xeno further, and the ways that, as the layers are peeled back, like the bandages wrapped around his head, the influence of David Bowie (the king of reinvention) can be seen all the more clearly, but instead I’d like to focus on the ending of Gula.

It’s a quiet scene on a dock involving Cass and a companion. He asks her if everything’s going to be okay. In the original printing of the issue, she replies "Yes", but in the subsequent printings, like the hardcover, her response has become "What do you think?". The belief that it will be okay, doesn’t just apply to Casanova, the character, who in the final panel of the issue seems to be basking in the belief that it will, but also to Matt Fraction and Casanova, the book. He altered the line of dialogue because he believed that it would make for a better end-of-book beat. In the grand scheme of things, the mere existence of that belief is what counts the most.

Matt Sibley is a comics critic with Best Shots at Newsarama, who has contributed to the site for many years. Since 2016 in fact.