How Marvel Comics fooled comic book censors by turning Vampires into Dinosaurs

Marvel Comics' tradition of horror heroes started by tricking old school comic book censors with dinosaurs

The post-credits scene of Venom: Let There Be Carnage opens up some interesting possibilities for the future of Sony Pictures' budding Spider-Man adjacent film universe, which next expands with January 28, 2022's Morbius, based on the infamous Marvel vampire.

The film's previously released trailer shows strong horror movie elements involved in scientist Michael Morbius' transformation into a so-called 'Living Vampire' - along with possible connections to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, which may or may not exist in the same continuity as Sony's films at this point.

Despite being more of a cult favorite than a household name, Morbius the Living Vampire holds a special place in Marvel lore.

Though Marvel Comics featured vampire characters in its early days as Timely Comics and its subsequent Atlas Comics era, the 1954 implementation of the Comics Code Authority prohibited the depiction of the undead in comics, including zombies and vampires.

Morbius is the first character to be billed directly as a vampire in the Marvel Universe 17 years after the implementation of the CCA (hence Morbius' caveat of being a 'Living' vampire). But Morbius isn't Marvel's first attempt to skirt around the censorship rules of the era.

In fact, Marvel's first big vampire villain wasn't technically a vampire at all - but a dinosaur.

How and why did Marvel decide a dinosaur-human-hybrid monster was the right choice to depict a non-vampiric vampire? And why is a vampire dinosaur so freakin' awesome?

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

We can answer the first question - but the latter should be obvious already.

So put on your Alan Grant style hat and your Ellie Sattler khaki shorts and get ready to play paleontologist as we dig into the bones of Marvel's vampire dinosaur, Sauron, and the circumstances that led to his creation.

Vampiresaurus Rex

Right off the bat (get it?) you may be asking, why couldn't Marvel just use a vampire in their comic books - especially if they had done it before.

In the '50s, mainstream comic books underwent a period of intense scrutiny in which popular psychologists began analyzing and blaming comic books for a perceived increase in societal ills and immorality (at least according to the ideals of the time). Similar to what modern fans have witnessed with alarmism over violent video games or certain genres of music, comic books began taking the blame for changing cultural attitudes.

The result was the 1954 implementation of the Comics Code Authority, a governing body similar to the Motion Picture Association of America's ratings board, which analyzed and censored comic books of all genres, and ultimately gave its seal of approval to those that met its stringent content standards.

The CCA's regulations included prohibiting the depiction of explicit violence, sexuality, and drug use in comics, but the limits didn't stop there. Along with these controversial topics, the CCA went so far as to ban the depiction of numerous fantasy and sci-fi elements it deemed inappropriate - including straight-up banning the depiction of common horror monsters such as vampires and werewolves.

Maybe they thought kids would go from tying towels around their necks to play Superman to literally drinking blood and howling under a full moon? Some of the actual assertions brought about by the moral panic over comic books aren't too far off from such fantastic fears.

But in the late '60s, Marvel Comics - ever the innovators - found a way to dig into some of these banned ideas without losing the security of the CCA stamp that code-approved comic books bore on their covers for decades: they'd use dinosaurs.

When writer Roy Thomas and artist Neal Adams took over the Uncanny X-Men title in the late '60s, Thomas set about revamping the team's adventures and adding some new antagonists for the X-Men to fight. Settling on his interest in vampires for inspiration, Thomas brought in the concept of Karl Lykos, AKA Sauron - a villain with the vampiric power to drain the lifeforce of his victims to sustain himself (pay no attention CCA, no blood-drinking going on here!).

But despite efforts to separate the concept of a vampire from the aspects of vampire mythology that were then in violation of the Comics Code, Adams' mutated bat-like design for the character was deemed to bring the concept too close to an actual vampire for the CCA's comfort, necessitating design changes to make Sauron acceptable.

Thomas and Adams took the main feature of their bat-creature - his massive, leathery wings - and twisted the rest of the design to resemble a pteranodon, a winged, crested dinosaur in the pterosaur family of great reptiles (for the paleontologists among us, we'll take this moment to acknowledge that pterosaurs aren't technically dinosaurs, despite their cultural associations).

Taking the design away from a bat-inspired direction also allowed Thomas and Adams to give Sauron even more vampire-like powers, establishing that the villain turns into his dinosaur-like form after absorbing life force, and adding a hypnotic stare to his arsenal.

And with that, Thomas and Adams had found the way to game the Comics Code Authority's guidelines against horror characters - by going in a totally unexpected direction and making their bat monster into a dastardly dinosaur (we know, we know - pterosaur).

Sauron (whose name is taken from JRR Tolkien's Lord of the Rings - Sauron himself even says so on the page) debuted in 1969's Uncanny X-Men #60, going on to become a recurring villain for the X-Men with appearances in cartoons and video games, and even a place of honor as one of the first figures released in the beloved '90s Toy Biz X-Men action figure line.

Oddly enough though, Adams and Thomas's vampire-centric storytelling wouldn't stop there, even after the creative team split, with Adams leaving Marvel entirely to work at DC.

Blood Ties

By 1970, just a year after co-creating Sauron, Adams had become massively popular as the artist of several of DC's Batman titles. In the landmark Detective Comics #400, Adams, writer Frank Robbins, and editor Julius Schwarz introduced Man-Bat, the alter ego of scientist Kirk Langstrom, who becomes a giant, humanoid bat when he takes a special serum of his own making.

It's probably not a coincidence that just a little while after his human-bat-hybrid design was rejected at Marvel, Neal Adams introduced a similar character at DC - notice that Kirk Langstrom and Karl Lykos even have the same initials. And despite seemingly skirting the Comics Code Authorities rules against depicting vampires (and, in a way, werewolves too), Man-Bat made it to the page.

Man-Bat's introduction in the DC Universe was indicative of changes to come in the CCA's rules around horror characters - changes which put Roy Thomas back in mind of vampires when he took over writing Amazing Spider-Man for longtime writer (and co-creator) Stan Lee.

Lee's departure from the title once again took Peter Parker in a mad science direction, with Lee's final plot for Amazing Spider-Man #100 involving Peter taking a special serum meant to eliminate his spider-powers and allow him to live a normal life.

But instead of the desired effects, Peter becomes somehow even more spider-like, growing four extra arms out of his torso - undergoing his own spider transformation thanks to a special serum. Is this the influence of Man-Bat coming back around to Marvel? It's hard to say - but years later Spider-Man: The Animated Series adapted the story taking it even further with Peter's serum transforming him into a full-on Man-Spider (yes, name included).

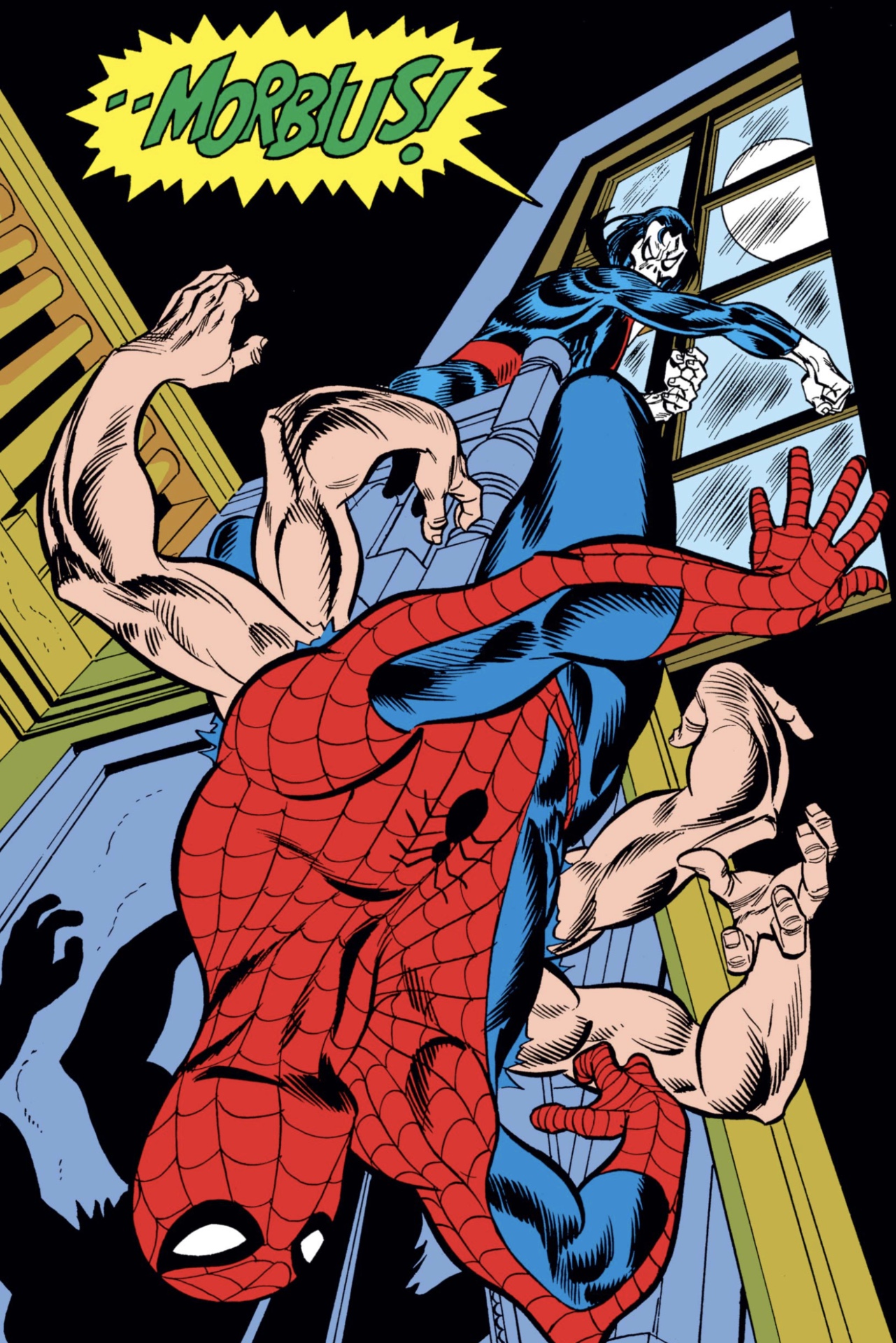

For Thomas' part, he and artist Gil Kane picked up the tale in Amazing Spider-Man #101 by having Peter Parker visit geneticist Dr. Michael Morbius, whose research into his own rare blood disease turned him into a vampire-like creature who feeds on that pseudo-science catchall of 'lifeforce' rather than blood. And in this way, Morbius the Living Vampire, as he quickly came to be called, followed Thomas' initial idea of a vampire-like character whose powers come from science rather than mysticism that was first adapted into Sauron.

Not long after Morbius' introduction, Marvel Comics leaned even further into horror, thanks to the continued relaxation of CCA restrictions on horror characters, introducing their own version of Bram Stoker's Dracula whose title, House of Dracula, spun-off characters such as Blade, Werewolf By Night, and more.

And, in an appropriate full-circle moment, Dracula even fought the X-Men in a fan-favorite story (appropriately titled X-Men Vs. Dracula), in which he temporarily turned Storm into a vampire.

And as for Roy Thomas, he kept on with his penchant for bringing horror into superhero comics by turning J. Jonah Jameson's son John Jameson into Man-Wolf - another version of a classic horror movie monster with a twist.

Marvel's Dracula remains a presence in the Marvel Universe, with the vampire lord recently feuding with X-Force and the Avengers in separate tales. And of course, Morbius is about to get his own Sony movie - with Blade the Vampire Hunter coming to the MCU in a reboot film, and Werewolf By Night spin-off character Moon Knight getting his own MCU show. And there are even reports that a version of Werewolf By Night will come to the MCU in a 2022 Disney Plus Halloween special.

And to think, Marvel's horror legacy all started with vampire dinosaurs.

Do you love the intersection of comic books and horror? Check out the best horror comics of all time as we head into spooky season.

I've been Newsarama's resident Marvel Comics expert and general comic book historian since 2011. I've also been the on-site reporter at most major comic conventions such as Comic-Con International: San Diego, New York Comic Con, and C2E2. Outside of comic journalism, I am the artist of many weird pictures, and the guitarist of many heavy riffs. (They/Them)