The perfect horror game, torn apart and reassembled

Games are a tough medium for horror. Giving the audience some measure of control over the action takes the power out of the hands of the creator. It means less creative control over tempo and atmosphere and more opportunities for the audience to break up the tension or examine the seams of an environment. Horror games are haunted houses without the immediacy of being physically present (though a growing number of VR experiences are getting us closer).

Despite all this, horror games are experiencing a massive uptick in popularity. Over the past couple of years they’ve become ubiquitous on Steam and are surging onto consoles as well. So how are designers doing it? In the spirit of the season, I decided to break down what makes some of the most successful horror games tick, what makes them both genuinely scary but also, if not exactly pleasant to play, not a chore. What are the choicest, meaty bits developers sew together to craft their Frankenstein’s monsters, and what is the lightning bolt that makes them twitch to life?

The chase

One of the things the recent crop of horror games does best is instil in players the sensation that they are prey. The tension of constantly being stalked by some sinister force, the idea that a brutal end might lie concealed in every pooled shadow, is one of the best ways games build atmosphere while maintaining player agency.

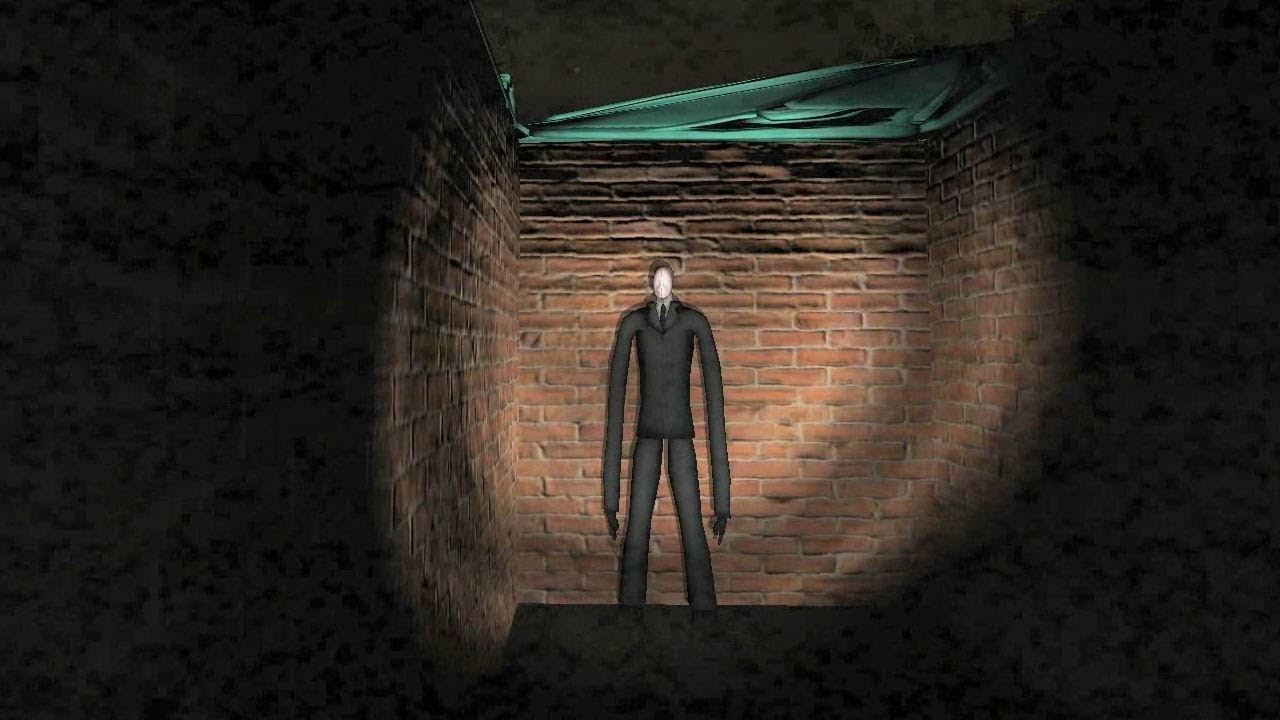

One of the best examples of this constant tension is a game that shepherded in this new era of horror gaming: Slender: The Eight Pages. An otherwise simple premise, walking around a dark forest with a flashlight and collecting pages, becomes an exercise in terror when you introduce a bizarre supernatural predator. The nerve jangling piano stingers and lanky, pale-faced horror of the Slender Man are powerful incentive to keep running and never stop.

Slender is a great example of building memorable scares through restraint. By only showing their monster in brief, terrifying glimpses, all the moments when you’re not facing him are freighted with tense anticipation. The most important lesson Slender imparts is that anticipating a scare is often more effective than the scare itself.

The jump scare

All of that said, the jump scare remains one the most important and effective weapons in the horror arsenal. They’re the crescendo that pays off all that carefully accumulated tension, a moment of both terror and a perverse sort of relief. Slender does an excellent job of dropping these in at appropriate intervals, but few games have perfected the jump scare as well as Five Nights at Freddy’s.

One of the reasons the jumps in Freddy’s are so effectively terrifying is the slow, inexorable build to them. Watching as creepily grimacing, half-lit animatronic creatures trundle towards you down shadowy corridors gets increasingly unsettling the closer they get to where your paralyzed avatar sits, helplessly flipping from monitor to monitor as the murderous children’s amusements approach. Why are these stuffed animals so toothy, anyway?

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Freddy’s capitalizes on a number of classic tropes to make its scares so intense. Subverting elements you normally find in the innocent realm of children’s entertainment, freezing the protagonist so escape is impossible. When the scares do happen, a chittering animatronic nightmare latching murderously onto your character, the stage has been set so masterfully that the shock is palpable, like a physical blow.

Body horror and violent psychosis

There’s another school of horror that takes a very different tack, that seeks to frighten its audience by disgusting and disturbing them rather than relying on the peaks and valleys of jump scares. Instead of building tension, these games build an atmosphere of pervasive, visceral and psychological horror through the exhibition of gore and brutal acts of violence.

Games like Outlast and its Whistleblower DLC aren’t interested in occasionally startling players as much as presenting a hellish descent into madness. They accomplish this in part by employing a powerful tool available to game makers, forcing players to not only empathize with but inhabit characters that are subjected to violence, torture, and the gruesome consequences of their own actions. And they litter these games with the paraphernalia of human butchery: shelves of disembodied human heads, bodies on hooks, the screams of the dying as they’re immolated by flame. Driving all this gore, Outlast’s twisted Variants, mental patients twisted by experimentation, paint a thin veneer of humanity on deeply sub-human behavior. And while the game is much more interested in showing what happens when the mask slips than in humanizing its monsters, that slim vestige of empathy makes all the bloodshed and carnage even more unsettling.

The psychology of man

By contrast, games like Soma eschew blood and gore for a narrative hinged on one simple, core question: how do we define humanity? It manages to unsettle by stretching and distending the limits of the way we think of and define ourselves and the people we identify with.

Soma starts with some core uncertainty about the nature of the player character, and continues to heighten that uncertainty by presenting players with malfunctioning robots, little more than shattered heaps of mechanical parts in pools of oil gushing from their ruptured seams, that identify as humans. Their confusion (and fear) when the player refuses to recognize them as human is reflected in confusion about the player’s own identity and role in the world.

Soma leans into a brand of psychological horror that has rarely been attempted in games and pulls it off with surprising deftness and aplomb. While it stumbles over mechanics at times, its ability to plumb the philosophical depths of identity in powerful and unsettling ways is second to none in this medium.

The sum of their parts

While each of these games is defined by core premise, they all borrow liberally from other games and established horror tropes. But the lesson these games all teach is that, when assembling a shambling horror, it’s important to start with a strong heart and build out. Everything else is just flesh.

Alan Bradley was once a Hardware Writer for GamesRadar and PC Gamer, specialising in PC hardware. But, Alan is now a freelance journalist. He has bylines at Rolling Stone, Gamasutra, Variety, and more.