The pleasure of a good card game - and why The Witcher 3 gets it wrong

A quick warning: this article contains a NSFW video, and what could be considered a tiny spoiler for The Witcher 3. Also, I admit to playing Magic: The Gathering so, you know, be prepared

I’m sure a learned wit of some kind has extolled the virtue of a good game of cards, but I think the idea’s best summed up by this uncomfortable little scene from peerless character-comedy, Louie:

The poker game’s tangential to what’s really going on – a conversation that swings from scatological to significant in the snap of an expletive – but there’s a reason Louis C.K. chose it as the setting for his scene. The majority of card game variants might be what you call “passive games” – no matter the amount of strategy needed to play well, it’s a medium where the majority of time is spent sitting still, waiting, thinking.

Unless you’re at the kind of tournament where they stick cameras under your hand and people wear cowboy hats indoors without irony, you fill that time by talking, making jokes, drinking. Often, it’s more social event than game – I’ve played more real-life Magic: The Gathering than my ego would like me to admit, but I’ve only played for a prize twice (and even then, one time, I talked to a sweaty Italian man in a suit enough that I lost focus, made a mistake and he called a judge to try and get me disqualified).

Card games, in the way they draw multiple people together over a single pursuit, force you to interact, breed conversation. The pleasure of time spent talking becomes as much a reason to play as the game itself. It’s why that Louie scene works so well. It’s more private than a chat in a bar, more casual than dinner conversation. Anyone who’s trash-talked in an online game will understand why there’s as much aggression as there is friendliness at that table. It’s exactly the kind of place where name-calling becomes soul-searching and flips back again.

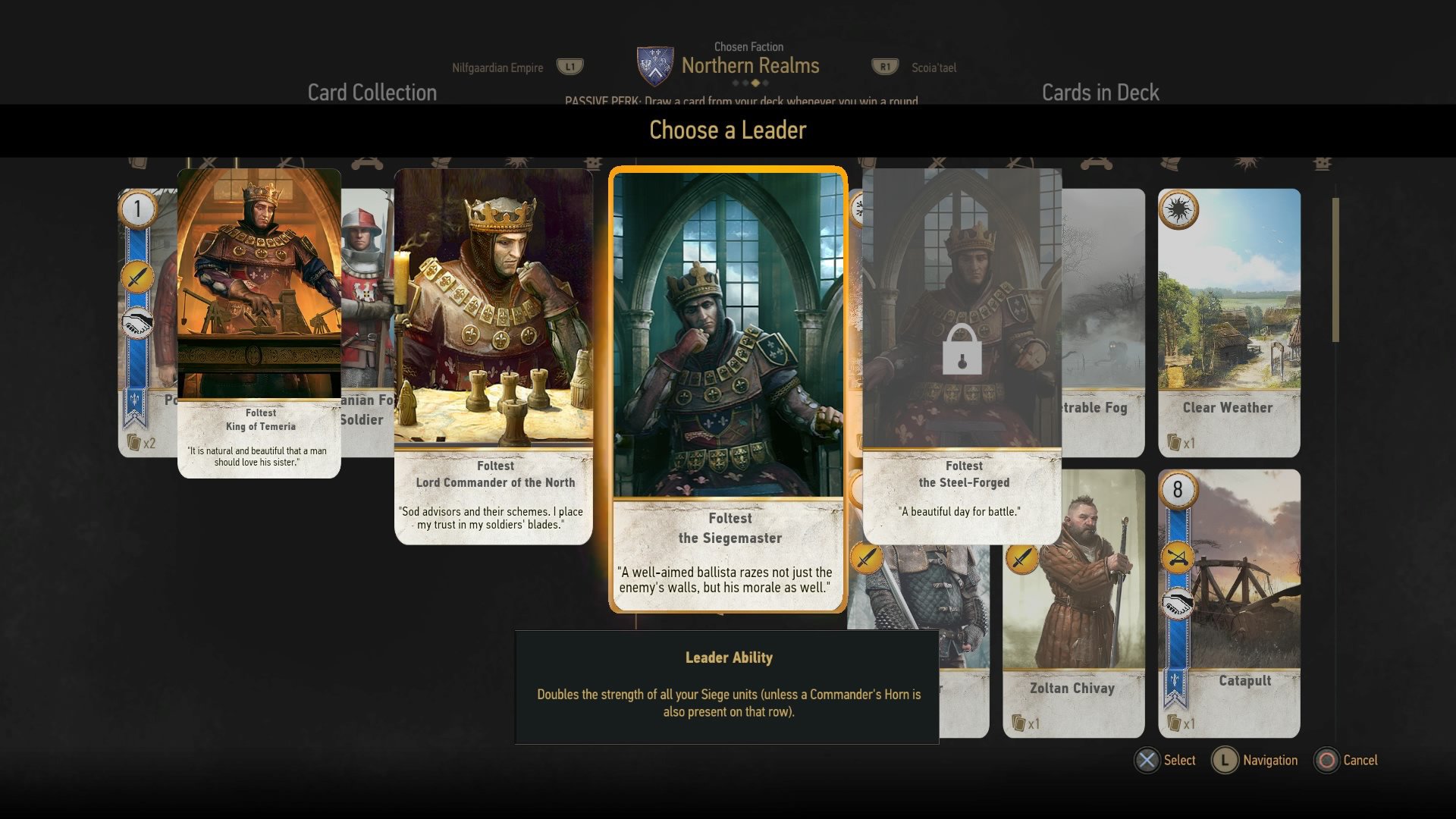

There’s a reason so many games (and particularly RPGs) include card games as a sideline – but it’s not the same one. Triple Triad, Pazaak, Red Dead Redemption’s Poker; all live on in my mind as moments where I got to disconnect from the woes of grinding, or cosmic destruction, or dead horses. In fact, in The Witcher 3, Geralt will occasionally sum it up perfectly as he asks whatever hapless innkeeper I’m about to annihilate for a game of Gwent. “Need a diversion”, he’ll grumble, as I unsheathe my disgustingly efficient Nilfgaardian Empire Decoy deck.

And then, silence.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

In almost every example, these games are separate from their grand-scale containers. You get a close-up view of an identical table every time, a few sound effects, some background music. The closest they tend to get to integration in the main game is as a gussied-up collectibles quest.

Red Dead went a little further, I suppose, as its players spat out canned phrases while you played, and tried to shoot you if they caught you cheating. The Witcher goes further by building Gwent into the fabric of a couple of encounters. One memorable side-quest makes the term “high-stakes” look a little silly as you play for someone’s life - but even then you cut from a conversation thick with tension to Gwent-vision (essentially, a close-up of a wooden chopping board upon which cards move themselves about swiftly enough to make swishing sounds, as if manipulated by a nervous ghost).

Geralt and his opponent don’t talk – you’d think the bad guy would be crowing, or the man-turned-prize pot might have something to say about your choice to play a Scorch card to get rid of a five-strength archer when you’ve forgotten you can summon an Impenetrable Fog at no cost, you fucking idiot.

My point being that if titles like The Witcher are starting to make their card games more than distractions, it would be extremely cool to see them attempt to approximate something of what makes that Louie scene so special. I’m not naïve enough to say this would be easy, or even particularly useful to the game as a whole – but I am naïve enough to say that one game that I know of attempts this trick, and that that means others should try to take it on too.

Inkle Studios has done a great many amazing things with its slew of iOS games, but one of the least sung about is how it weaves story into its Sorcery! series’ own game-within-a-game, Swindlestones. It’s a variant of Liar’s Dice, basically, but as you play, your bids in the game are tied to lines of conversation – little questions about the other player, or the location you’re heading towards at the time.

It means each turn is both a gamble and a dialogue choice, to which your opponent replies on their turn. Not only is that neat as all hell, it becomes another game of its own – there were moments where I would purposely make bad calls, just to follow a more interesting line of thought. Can I recover from losing this round, just to hear about this witch’s childhood? Fascinating.

I don’t think any Swindlestones conversation rustles the game’s storyline branches (I say “think” because Sorcery! encompasses literally thousands of meaningful choices so, really, who knows), but it certainly adds to my enjoyment, and my willingness to play more of the minigame.

In a game as willing to take it slow as The Witcher 3 - where chance conversations are often more engaging, and more harrowing, than world-changing decisions - this would fit perfectly. Listening to an opponent chat away about life as a travelling merchant could serve world-building, quest-giving and joke-telling functions.

It could be mechanical - win a round and they give you a clue to some hidden treasure, lose it and they call you a mother-plougher. It could be dynamic – Gwent’s cards depict historical figures from the game’s lore, and the idea of hearing another Witcher’s take on Yennifer when she comes up in the game would be a fascinating little diversion.

Or it could just be a little more true to life. That Louie sketch doesn’t just cut to the core of how a meaningless game can bring out the most important human moments – it also shows a group of comedians offstage, in the kind of situation we’re not usually privy to. Some jokes fall flat, much of the scene isn’t played for laughs at all. I’d welcome a chance to see Geralt and his ilk on their downtime. In a medium where developers obsessively search for realism, the reality is that, sometimes, a game of cards and a chat is all we need. Maybe our characters could do with one too.