Comic books' crazy 1996 revisited: a wedding, a bankruptcy, a DC-Marvel crossover, more

You thought 2020 was a crazy year for comics? Let's go back to 1996

Imagine a year where Marvel and DC absolutely crush its sales, but the House of Ideas almost implodes and the industry is wracked by business failures. And in the background, your computer starts talking to you.

This year happened, 25 years ago. Remember 1996? Many titans of the comics industry still do.

Setting the stage

Context is everything, right? As 1996 started, things looked like this…

- Comic books enjoyed a massive boom period from about 1989 to 1993. But by mid-1993, a 'speculator bubble' had burst, print runs crashed, and many stores went out of business.

- In 1991, in the midst of the boom, financier Ron Perelman bought Marvel Comics and used Marvel stock to secure junk bonds to acquire other companies.

- In 1992, major Marvel talent including Jim Lee, Rob Liefeld, Todd McFarlane, and others left the company to form Image Comics.

- In 1994, Marvel bought Heroes World, one of the 17-or-so distributors that trafficked comics from publishers to stores. In 1995, Marvel started self-distributing, throwing the other distributors into chaos.

- X-Men ruled the roost in sales. As the year began, eight of the industry's 10 top-selling books were X-family titles.

- Superman was a good seller for DC but typically didn't hit sales charts until you hit about no. 20.

- Something called 'America Online' was achieving broad cultural awareness, and free AOL startup discs started appearing nearly everywhere.

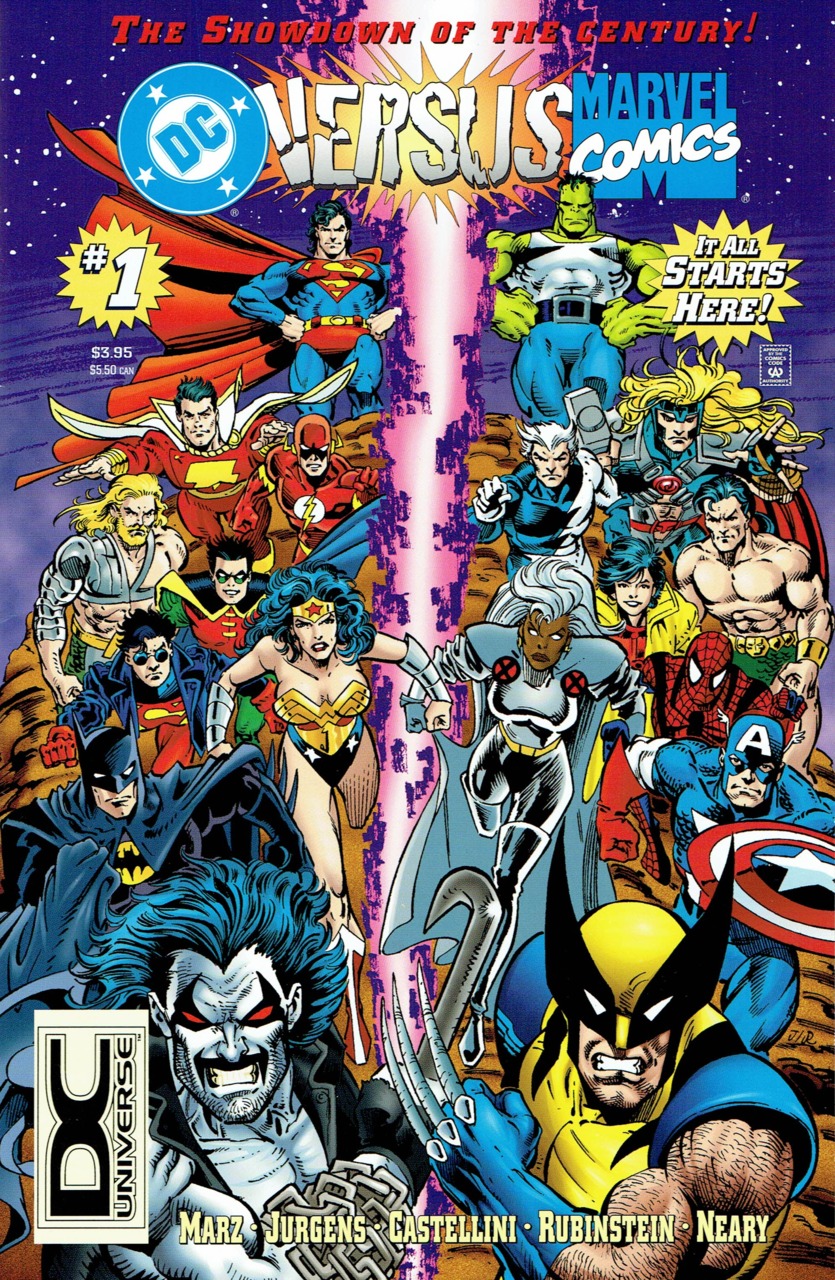

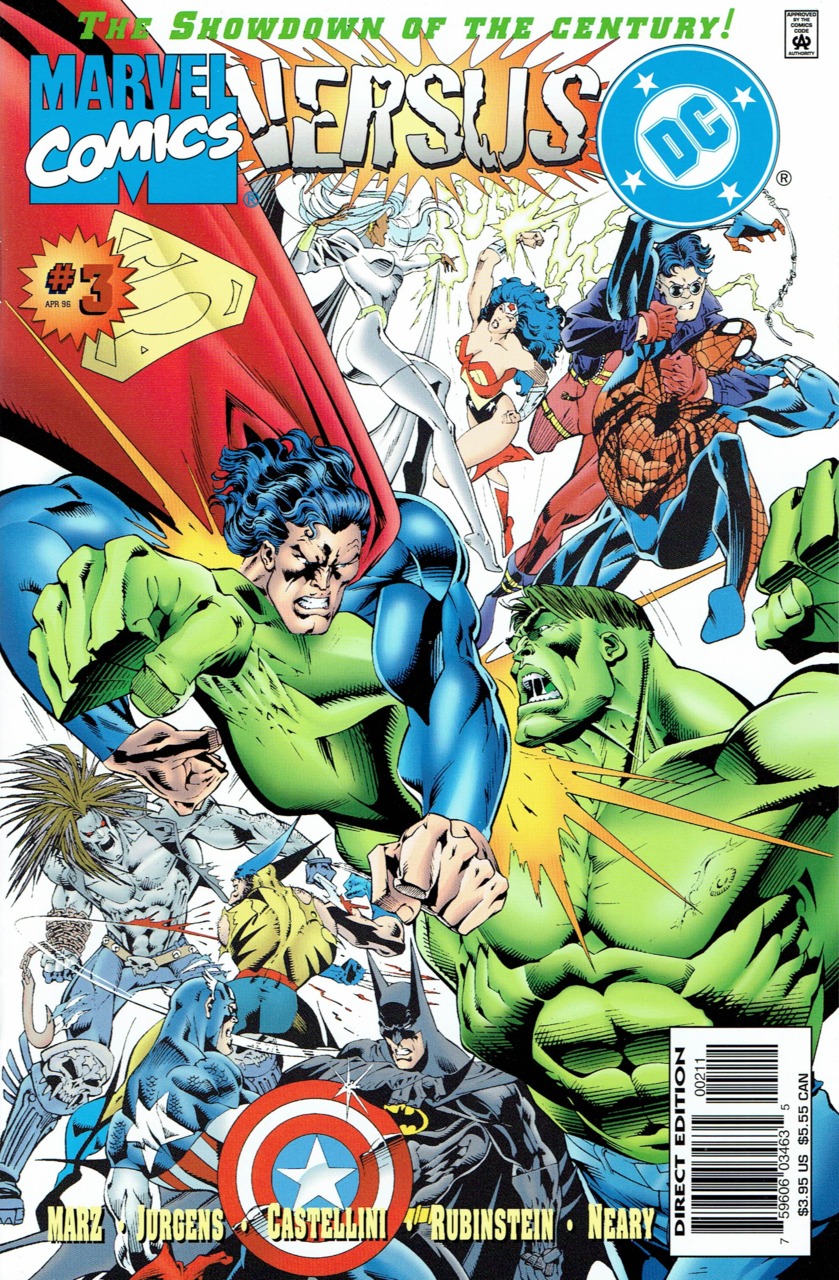

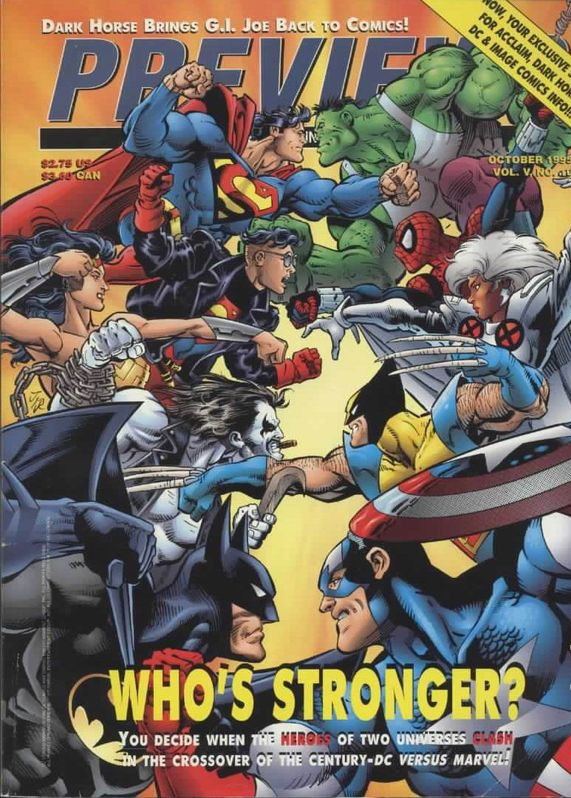

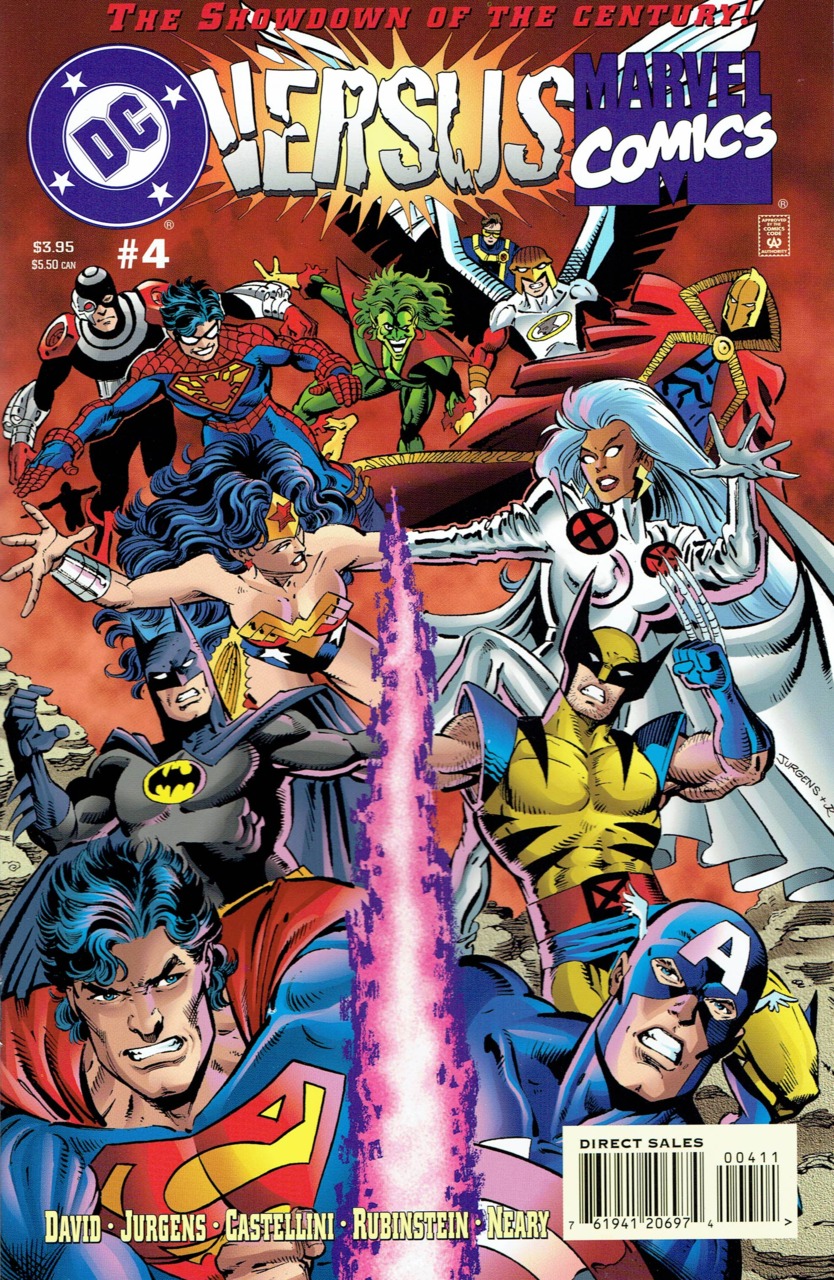

DC versus Marvel... and Amalgam

Sales were in freefall. The industry was ridiculously top-heavy with X-Men. Retailers were hurting. Comic books needed a lead-pipe cinch, a surefire winner. At 1700 Broadway in New York, the phone rang on the desk of DC's then-publisher, Paul Levitz. It was Marvel's then-president Terry Stewart. And he had an idea: A four-issue limited series in which all of Marvel's characters could meet all of DC's.

"The thing basically starting with Terry and his concern and frustration with the shape that the market was in," Levitz remembers. "We needed to get people back in the shops."

Two issues were titled simply DC versus Marvel; the other two Marvel versus DC. Marvel would provide a writer and artist team, and DC would do the same. Superman artist Dan Jurgens was tapped as an artist on the DC side. He recalls the market urgency.

"One of the reasons that this project came together in the first place was that Marvel and DC both had a genuine desire to give the market something that would really help out retailers," Jurgens says. "In comics, we tend to be a group of people for whom the sky is always falling, and the distributor wars had created a lot of uncertainty. This was something the retailers could really chew on and sell a bunch of copies of."

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

The launch was economic. But the soul of the project was a buddy-cop movie starring Marvel editor Mark Gruenwald and DC editor Mike Carlin. Carlin had started as Gruenwald's assistant at Marvel before moving to DC. The two were longtime friends who breathed life into the project - in secret early on.

"This was so hush-hush that only the highest echelons at Marvel and DC knew it was happening at first," says Ron Marz, the writer of DC's half. "I got invited to the party by Mike Carlin, who told me not to tell anyone. I think I told my wife, and I then told her not to tell anyone. But I certainly didn't let any of my friends or colleagues in the business know until it was announced."

The initial creative meeting was cloak-and-dagger.

"Our first meeting for the project was at Mark Gruenwald's apartment," Marz says. "They didn't do it at either office because the editorial staffs at each company didn't know it was happening. It was me, Mark, Mike Carlin, and [Marvel writer] Peter David, and we hammered out the whole framework of the thing."

Inevitable Marvel vs. DC character battles would happen, with fan voting determining the results. That created its own odd dynamic, as in a comic universe vacuum, the planned Wolverine vs. Lobo would seem to be an easy win for Lobo. But voting by faithful fandom would (and did) tip things in Wolverine's favor. Both contingencies were planned for.

"We knew going in that fans were going to vote, and I think we were willing to concede that Wolverine was likely going to win that," laughs Dan Jurgens, who drew the Wolverine vs. Lobo sequence. "But we did two versions of each battle. As soon as it was clear who was going to win the fan vote, bam, we'd put in the correct finished art."

The DC vs. Marvel project was exactly the tonic that retailers needed. The issues became the top sellers the industry had seen in years and continued to pay off with Amalgam Comics, a series of one-shots that featured mashed-up Marvel/DC characters: The JLA and the X-Men became JLX, Dr. Strange and Dr. Fate combined to become Dr. Strangefate, and so on. And at the end of it all, the fanboy-unthinkable almost happened: Marvel and DC almost decided to permanently swap two characters.

"I don't know that the idea lasted more than one meeting with me or someone just throwing up on the table and saying, ‘Oh, God, that is so much more work than it could possibly be worth,'" Paul Levitz recalls. "I think the idea was characters that we wouldn't necessarily miss, but could potentially make more valuable by generating new interest in another universe."

Ron Marz's memory is more acute on the subject.

"The characters discussed were She-Hulk and Martian Manhunter," he says. "I felt like those were great picks because at least in terms of power sets, they're kind of redundant characters. She-Hulk is, well, a lady Hulk. And Martian Manhunter is pretty close to Superman, just green with a big brow. They both would've seemed more original in the opposite universe. Again, from what I remember, the idea was a one-year term, at which point the characters go back to their home universes, possibly to be replaced by another swap of characters."

The swap never happened. But Marvel vs. DC put some fire in the bellies of readers, and some much-needed cash in the registers of stores.

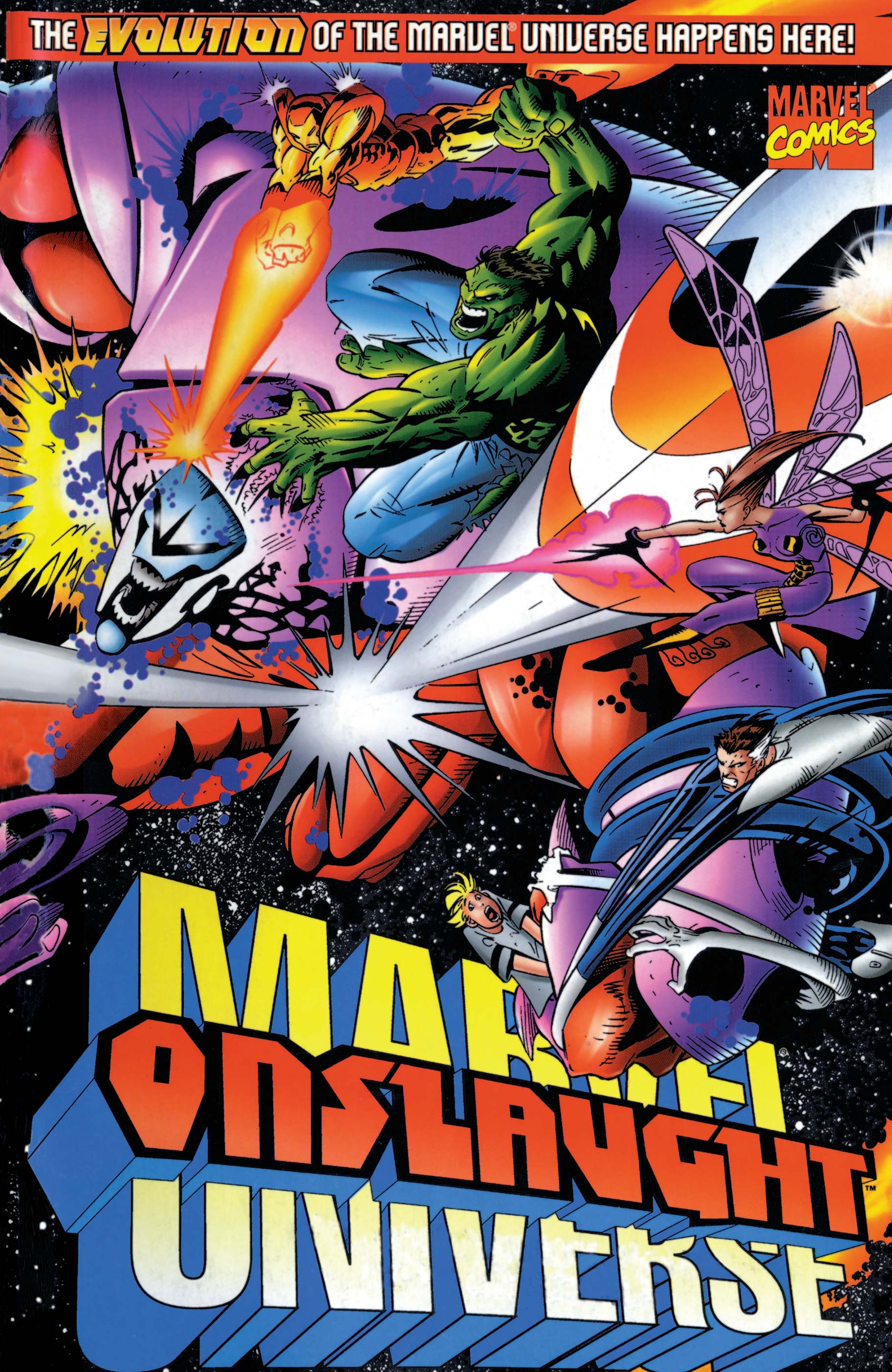

Onslaught

Remember X-Men ruling the roost? Strange things happened in those days, according to then-Uncanny X-Men writer Scott Lobdell.

"We had an X-Men story conference, and we were asked ‘If you could do any story, what would it be?'" he recalls. "I said I wanted to do a story where the X-Men are at home, they hear a noise, they run outside, and there's Juggernaut pile-driven into the ground with this five-mile ditch that he's impacted out before finally stopping and when they ask him what happened, he just says ‘Onslaught' and passes out."

Lobdell's concept seemed like a winner, even though he didn't know where to go next.

"Everybody said, 'Yeah, go ahead,' but that was all I had," he recalls. "I didn't know who Onslaught was at that point."

Building up a mystery around Onslaught and his identity became a Marvel editorial priority. And Onslaught became a bridge to an even more pivotal Marvel move.

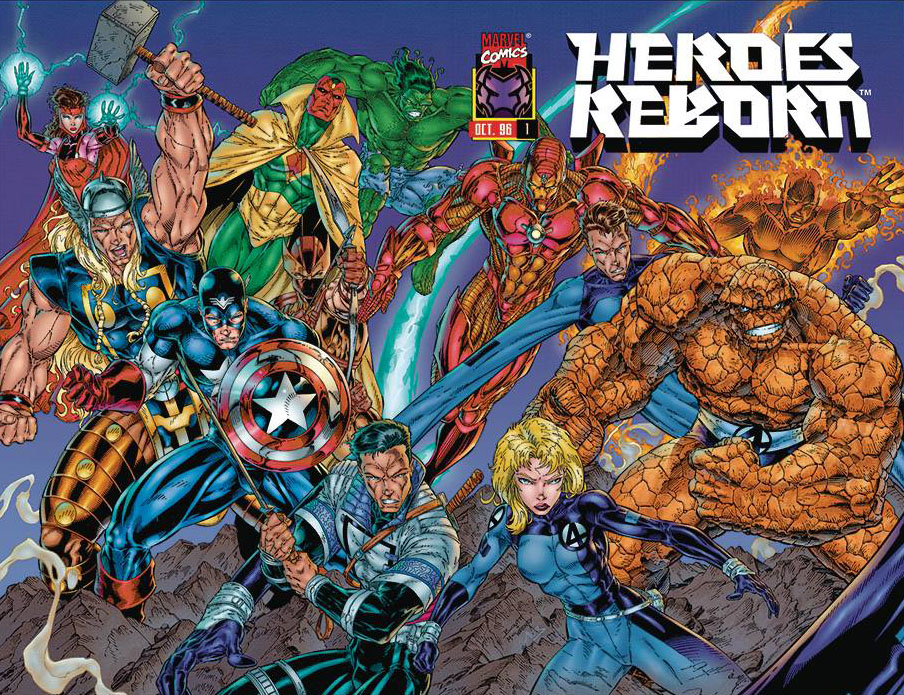

Heroes Reborn

Remember X-Men ruling the roost? Much of the rest of the Marvel Universe was stuck in a rut, with mediocre sales and not much excitement. And then, the unthinkable happened.

Marvel announced 'Heroes Reborn,' in which four longstanding Marvel titles -Avengers, Captain America, Fantastic Four, and Iron Man - would be outsourced to the creative studios of former Marvel talents Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld, where they would get new origins and new #1 issues in a separate "pocket universe." The 12-month deal was a business decision, through and through. The creators were paid very high fees but had to achieve very high sales.

The decision blindsided Marvel editorial, and many saw it as a repudiation of its work. Editors went into scramble mode, and rising star Carlos Pacheco was put on Fantastic Four #415-#416, the final two issues before the title went off into the 'Heroes Reborn' deal, to show management how good the titles could be. But the die had already been cast.

"Almost everyone at Marvel was upset when they found out," Scott Lobdell recalls. "From the top down, the company had grown so frustrated with editorial's efforts to jump-start sales that they were going to turn to outside vendors to re-imagine those properties."

A story bridge was needed, and it was Onslaught.

"When word comes down that Marvel was shipping off those characters to another universe, me and [editor-in-chief] Bob Harras are sitting around trying to come up with a story that makes sense for the X-Men to stay where they are, but those other characters to go," Lobdell recalls. "The question became, ‘Who has that power?' And I said, well, ‘Onslaught can do it.' So we started to figure out why the X-Men would be involved too. But it was really once there was the need for Heroes Reborn, that we reverse-engineered the creation of Onslaught."

Tom Brevoort was a Marvel editor at the time and remains one to this day. He also recalls 'Heroes Reborn' as a seismic shift.

"It was definitely a sea change from anything that had gone on at Marvel previously," he says. "The idea that you would outsource characters like that was unexplored territory. It might have been the end of Marvel as a publishing institution, and the start of Marvel as a licensing agency that had characters placed all over with other people."

Strangely enough, Lobdell walked both sides of the street. He continued to write Uncanny X-Men for Marvel, and also wrote the new Iron Man in 'Heroes Reborn.' Not that it was easy.

"I was very, very disliked," Lobdell says today. "But I always wanted to do the next thing instead of the last thing. And this was the next thing. Plus, I've always thought the most important thing in this company [Marvel] is the characters, and not the creators or the editors or the marketers. For me, working on the character superseded any frustration and resentment felt by other people toward me."

Wrapped up in 'Heroes Reborn' was a poisoned chalice: Captain America. Cap was on the rise with a new creative team in writer Mark Waid and artist Ron Garney, who had started just a few months before the 'Heroes Reborn' deal was announced. But part of the deal it was, and despite rising sales and critical acclaim, Cap went off to the pocket universe. The new Cap and creator Rob Liefeld became a target of derision. To his credit, Liefeld tried to calm the storm.

"He got hold of me," Mark Waid says. "Rob faxed me his 22 pages of that first issue to ask if I wanted to dialogue it, to keep part of the continuity of the creators. I looked at it, and I said, ‘no thank you.' It just wasn't for me, this big, giant barrel-chested Captain America and the teenage sidekick. I just didn't feel good about it. But he did call me and offer me the gig of scripting over his plot and pencils."

'Heroes Reborn' had its own stops and starts. After six issues, citing that sales benchmarks hadn't been hit, Marvel canceled Liefeld's contract and reassigned his books to Lee. Then, as Marvel couldn't get its plans together in time to take the books back after 12 issues, they tacked a thirteenth issue on to 'Heroes Reborn.'

Marvel was plagued by even bigger problems. The company was dying under the weight of Ron Perelman's financial machinations.

"'Heroes Reborn' was announced, and three, four weeks later, they had a massive bloodletting here," Tom Brevoort remembers. "They let an enormous number of people go from every strata of Marvel."

Brevoort recalls the purge.

"You'd be sitting in your office, and the phone might ring. You'd be told to go down the hall to Bob Harras' office, and you'd be told you're getting cut. Someone from HR would be down there, too, and you'd get your severance. And once the first call came in, everybody up and down editorial row knew it was going on, and we're all living under the sword of Damocles, praying that phone doesn't ring."

The practical tragically met the symbolic on August 12, 1996, as beloved editor Mark Gruenwald died of a sudden heart attack. He was only 43 years old. The news crushed a staff that was already reeling from massive layoffs and frightful change.

"Literally, between the last 'regular' Captain America issues being finished and before the first 'Heroes Reborn' issues, Mark had died," Tom Brevoort recalls. "I know logically one has nothing to do with the other, but it seemed scary. It loomed large. It seemed like destiny saying, 'Yeah, this is the end of an era.'"

Kingdom Come

Marvel Comics was a house on fire, but DC Comics was the steady ship. DC polished its image yet more with a prestige project that offered a glimpse around the corner into its possible future - Kingdom Come.

The four-issue limited series was written by Mark Waid and featured lush, painted art by Alex Ross. Ross had come to DC with a 40-page handwritten outline and multiple character designs, but DC needed a partner for him.

"It was Alex's basic concept: heroes retire, new heroes show up," Mark Waid says. "He had a lot of really interesting drawings and designs, but not really any texture to it yet. It needed something, and that's where I came in because I was the DC Comics expert."

Kingdom Come was chock-full of Easter eggs, clever 'this could be the future' twists, and the entire cast of the DC Universe. It took the industry by storm, sweeping up awards and selling massive amounts. It also, inadvertently, helped fan a tiny spark that became a massive cultural blaze.

Rise of the Internet

"It was Kingdom Come that changed everything," says Jonah Weiland. "After I read that first issue, that was the day I decided I wanted to find a way into comics. That book created and drove a passion within me."

Weiland was one of many people futzing around this new-ish thing called 'the information superhighway' on 9600-baud modems in 1996. He already had a comics links webpage because Google didn't exist in 1996. He added an unofficial Kingdom Come fan page.

"I wanted to do some programming, create a community," Weiland remembers. "And after the four issues were done, I had a community that was posting upward of 250 times a day, which in 1996 terms, might have been the equivalent of millions of Tweets. It was pretty incredible and I felt responsible for this community. That became the basis for Comic Book Resources."

CBR.com became an internet comics juggernaut. But that wasn't Weiland's plan.

"It absolutely started as a hobby," he says. "I had no idea; I had no plan then. I was just having fun. It wasn't until three to four years later that between CBR and my other business, Boiling Point, a web hosting company, that I was able to quit my job. And I'll be honest, those first few years were pretty brutal on my pocketbook. But very shortly after that, I started to see the potential."

Part of the potential was seen at (self-awareness alert; yes, we know where this is being published) Newsarama. The site started as a weekly comics news summary at AnotherUniverse.com. Mike Doran and Matt Brady were the early principals in a medium that felt new and almost dangerous.

"Something was starting to coalesce," Brady recalls. "It was coming off of [early internet forums] Usenet, and more and more people were finding it. And there was a hunger for information. It was guerrilla, anyone writing about comics could find news tips on Usenet. There were friends of artists and people who shouldn't have talked and people who should have known better. 1996 was still early. It was a rattling in a box and people were taking a look at it."

Fans were certainly looking in the box, and creators were, too.

"There was speculation as to what the internet might someday mean for comics, but I don't think we could have foreseen the specifics," Dan Jurgens says. "We had a notion that 'someday you'll have a scanner and you'll be able to send your work over the internet,' but I don't remember anyone telling me that fandom would build itself around the internet and thus comic press and promotional events would be built solely around the internet. No one had the notion that you would read a comic on a phone which you would then put in your pocket. So of course, all that was massively transformational, but we didn't know it at the time."

Another massive transformation in the business was coming to its endgame as well.

Last comics distributor standing

Marvel bought Heroes World, a regional comic book distributor, in 1994. By 1995, Heroes World was Marvel's exclusive distributor. Suddenly, a distribution system that had existed in a delicate balance for 20 years was thrown into chaos.

"Considering that Marvel represented 30 to 35% of our volume, this was a catastrophic event for everyone," says Steve Geppi, president of Diamond Comic Distributors.

Diamond was the lead dog in the market with about 45% of the comic industry's volume. Capital City Distribution was a clear-cut second with about 30%. The other 15-or-so regional distributors made up the other 25%. Diamond and Capital City were gut-punched. The smaller players went out of business. But the stores were hurt the most.

"Retailers were severely damaged because Heroes World had no capacity to handle distribution outside its territory, and Marvel had no understanding of what logistics capacity Heroes World had," says Milton Griepp, then a co-owner of Capital City. "And the retail community is the foundation from which all money flows."

Heroes World was plagued by late shipments, missing shipments, and damaged shipments. And when a store doesn't get its Marvel books for even one week, it's hard to keep the doors open. Compounding the problem? The minute Heroes World became the exclusive Marvel distributor, it also became a failing business.

"They made the fatal mistake of telling the world they were not going to carry anything but Marvel," Steve Geppi remembers. "And even though all of Marvel's volume through Heroes World was significant, it wasn't significant enough alone to justify a cost-effective distribution system."

With Marvel cut out of the distribution pie, Diamond and Capital City were in a war to sign other publishers to exclusives. DC was the prize plum.

Diamond got DC, along with Dark Horse Comics and Image Comics.

Capital City got Kitchen Sink and Viz Media.

The writing was on the wall, and in July 1996, Capital City sold out to Diamond, leaving only Diamond and Heroes World standing. To the company's credit, Diamond bought Capital City. They didn't just wait for the company to go under, and then pick up the pieces.

"It was true that we would have been the only ones," Geppi says. "But it would not have been in my interests to see Capital go under. Because a lot of small publishers would have not been paid. If Capital couldn't pay these small publishers and even some of the larger ones, it would have been devastating for many of them. And that would hurt my business, ultimately. So I felt it was the right thing to do, and yes after we did the deal, every publisher that Capital owed money to got paid in full. It was a happy ending that came out of a bad situation."

Heroes World hung on into 1997 before collapsing, and Diamond took on Marvel's distribution. But make no mistake: In the interim, between a general market collapse and stores being pushed out of business in the distribution wars, the comics business lost 62% of its volume.

"In 1993, when Diamond was 45% of the business, the entire business was $500 million at wholesale. After Marvel came back and we were just about the whole world, we were only $186 million at wholesale," Steve Geppi says. "The industry capsized in the middle."

Geppi knows the Heroes World move forced the hand of distribution consolidation.

"But if you allow me to be what I will call very objective about this, this almost had to happen," he says. "The collective volume that the industry represented by 1996 or 1997 wasn't enough to support all those distributors. Having one distributor, with large publishers able to consolidate its marketing efforts in one place, and setting up, by and large, brokerage agreements where they set the discount schedule and the inventory was owned by them, allowed the distributor to go a bit deeper into inventory in small publishers. In an odd way, it may have been what saved the industry."

Geppi says in 2015, the comic industry finally rose back to its 1993 heights of $500 million at wholesale. It took over 20 years.

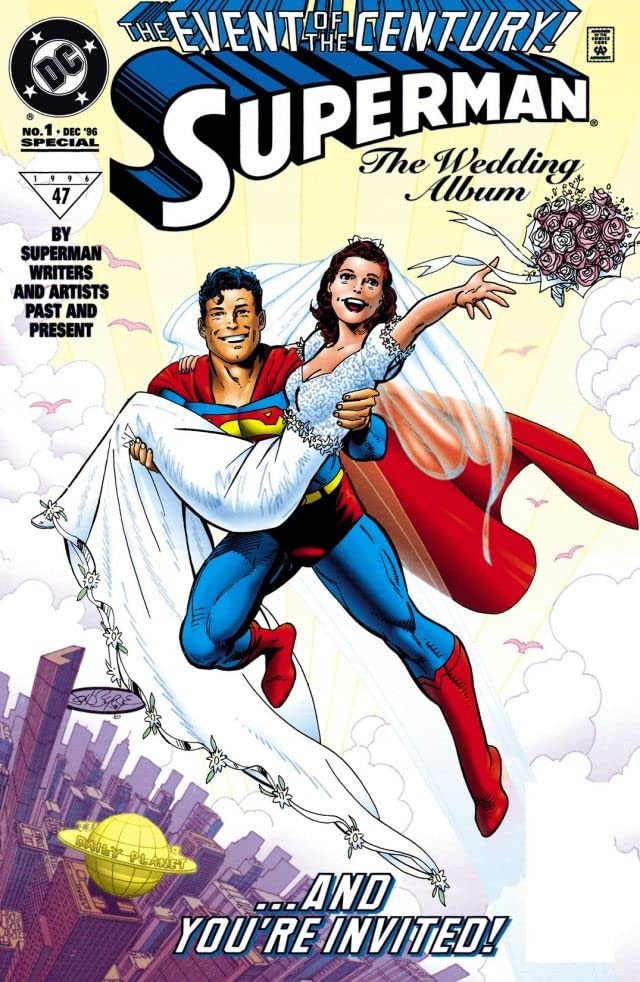

Superman gets married

The end of the year saw an important social occasion - the wedding of Superman and Lois Lane. Their engagement had been lingering a while…

"When we made the decision that Clark and Lois would get engaged [in 1990], it would be fair to say that we didn't have a hard date for when the wedding would take place," Superman writer/artist Dan Jurgens says. "We thought, who knows? Maybe it was a five, 10, 20-year engagement? We actually started to plan it for [1992's] Superman #75, which became something else entirely [the famous 'Death of Superman.'].

But the Superman: The Adventures of Lois and Clark TV show decided to marry the couple, and the comics quickly followed suit.

"When the TV guys decided, 'We have to do it in this season,' we decided that the comics had to match," then DC Comics publisher Paul Levitz recalls.

A Superman Wedding Album with contributions from dozens of writers and artists was planned.

"The Wedding Album gave us a chance to get everyone who was ever involved with Superman artistically who was still alive to get involved in the book," Jurgens says. "It even gave us a chance to use some [beloved longtime Superman artist] Curt Swan pages posthumously. It was great to get him involved in any way we could, to feel that presence. I still look back on it as a very special project, a very special book."

Tidbits, Impact, and the Future

Think about it: Marvel and DC did a company-wide, cooperative crossover with dozens of spinoffs. All for the good of the market. It was the reality in 1996 but seems impossible in today's world of walled-off IP kingdoms.

"When we did this, it was a comic project," Ron Marz says today. "But 20 years later, we're dealing with multi-billion dollar franchises and IP farms. That's what comics has grown into. I'm not saying that's good or bad; it's just the reality of the situation. These characters now, because of transmedia success, are now worth just untold hundreds of times more money than they were 20 years ago. And when they're owned by parent mega-corporations, the sort of freedom and fun we had doing it in 1996 is probably a thing of the past."

Or is it?

"If there's a pressing need, it could happen again," Tom Brevoort said in 2015. "The comics industry tends to work well when we need to, when there's a void to be filled. We seem to react better to adversity than to good times. But as Marvel and DC have become more vertically integrated businesses and not just publishing houses, it is more difficult to bridge that gap. Can it happen? Sure, it can. But the desire has to be there, and it has to be there at a high level. Because the concern now is not just what it means for Superman and Spider-Man to team up in this comic book, but also what does this mean for the movie properties? People who are involved in many, many different areas of the business would have to come together and see the benefit of such a thing. It's not impossible, but it is difficult."

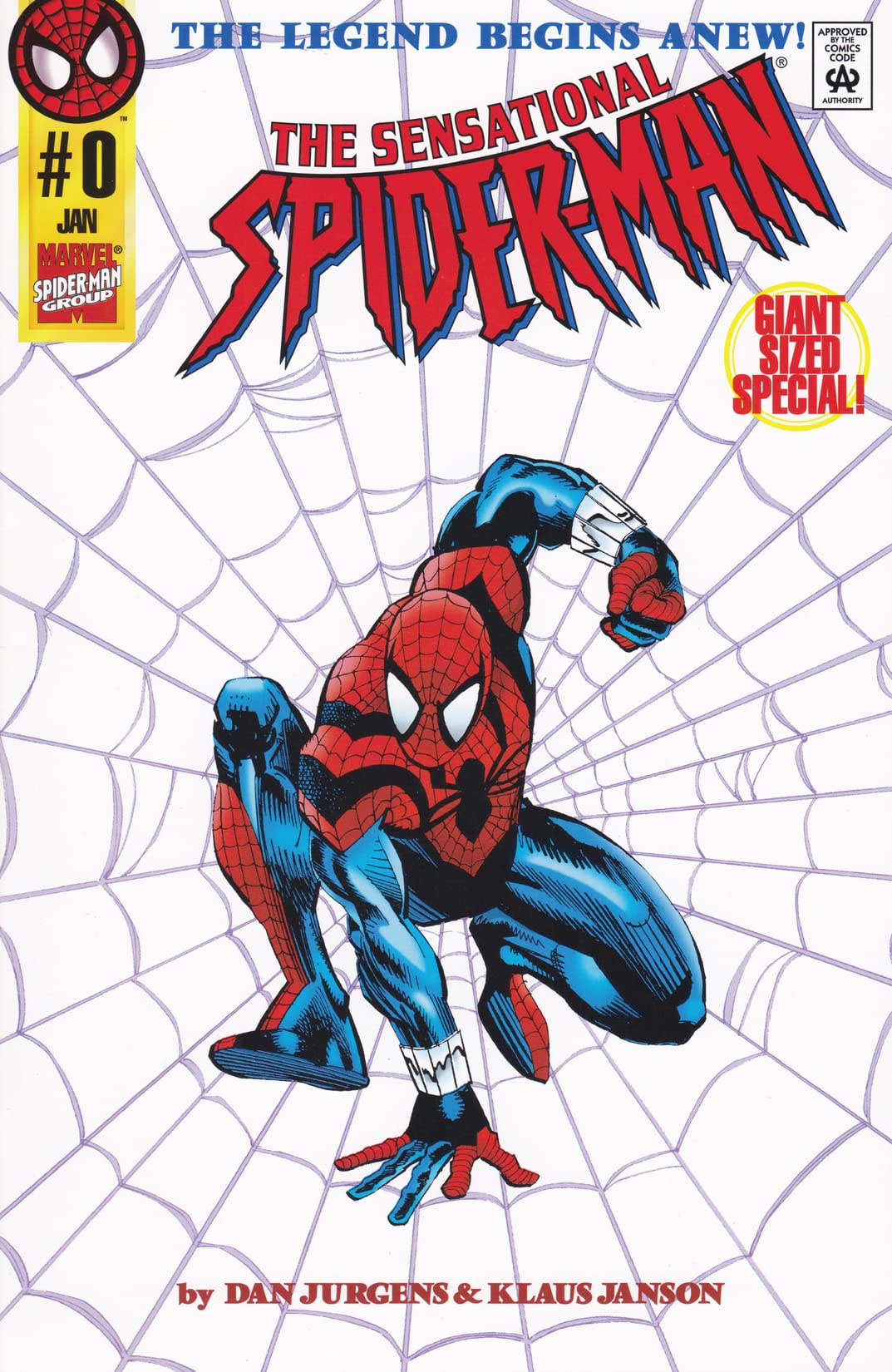

Dan Jurgens himself was an odd footnote in 1996: He was writing Sensational Spider-Man for Marvel and Superman for DC at the same time, something usually not done these days. It's not just the characters on a short leash - it's the talent, too.

"I think now, they [Marvel and DC] want to protect its plans a little more than they did then, and they're a little more concerned with the notion of ‘we're building a publishing plan for years,'" Jurgens says."And because of that, maybe they don't want its key players on key books sharing that across the street."

On the Marvel side of the street, 1996 ended poorly. The company entered Chapter 11 (reorganization) bankruptcy in December. Paul Levitz remembers it as a time of great sadness.

"The Marvel bankruptcy was an overwhelmingly strange thing," he says. "It was an odd bankruptcy because it wasn't that Marvel's business was failing, it was the financial engineering that Ron Perelman had done with the company's funds that had driven them into bankruptcy. It was sad to watch, and awful torture for the staffers living through it. I have tremendous respect for Bob Harras' work in that period, holding the whole editorial process together. To this day, I really can't figure out how the hell he did it."

But Levitz also thinks the legacy of 1996 was ultimately building a stronger business.

"The most long-lasting piece of this is the change in the distribution system," he says. "In many ways, it facilitated the growth of the graphic novel. For the most part, in the old system, a store retailer couldn't order a copy of the Watchmen [paperback] without ordering a box of 18. And no retailer could afford to carry 18 copies of Watchmen at a time, much less a full box of anything that sold less than Watchmen."

The brokerage agreements that Steve Geppi alluded to were drafted: publishers would own their own stock at Diamond's warehouses until the books were sold.

"We designed changes in the system so you could get onesies and twosies in the same way that they could in the traditional book business," Levitz says. "As soon as we changed that, the graphic novel business started to grow at a healthier pace."

Scott Lobdell sees today's relaunch and reboot culture (Hello, Star Trek; and what the heck, you, too, Space Jam) as having roots in 1996's 'Heroes Reborn.'

"Today it's become almost a monthly event, but at the time it was pretty staggering, and one could make the argument that this one single event opened the floodgates," Lobdell says. "And it set a precedent: Just a few years later, Marvel gave Jimmy Palmiotti and Joe Quesada Marvel Knights, and that begat the Ultimate line, which was sort of an in-house version of 'Heroes Reborn.'"

For his part, Dan Jurgens chooses to remember the good times.

"It reminds me how much fun the '90s were!" he says. "I know people love to rip 1990s comics in a lot of different ways, but man, you go through it, and we had a decade of things just happening at such a tremendous pace that it couldn't help but be fun, for fans, for pros, and for retailers. There was just so much happening."

Speaking of comic books' crazy 1996, we look at the best Marvel character that debuted in each year of the '90s as part of Marvel Yearbook, our six-part series celebrating 60 decades of the Marvel Universe.

—Similar articles of this ilk are archived on a crummy-looking blog. You can also follow @McLauchlin on Twitter