Chaos Theory is as good as traditional stealth gets, and rather than take on the series’ – and arguably Ubisoft’s - highest point, Conviction would discard the traditional model for something faster and more aggressive. Beland wanted players to feel “more like a panther than a grandmother,” but it was a process which everyone knew could make Sam an invincible superhero rather than the vulnerable agent he is.

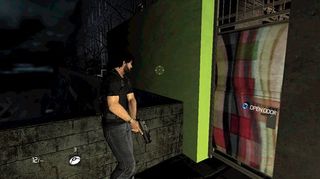

“You are Sam Fisher,” says Beland. “He’s the best agent in the world so he’s able to open the door and headshot three guys in the blink of an eye. Mark and Execute is the feature that lets players do that but we didn’t want it to be a win button. We had to balance it and we chose to do that with the hand-to-hand kill… It was a very difficult choice for us because you can’t just justify the mechanic in a realistic way. At the same time, when you play you’re always looking for that one lone guy and it makes it more fun. I think it creates a very good gameplay loop that’s different and feels fresh, and works well even though it exists ‘outside’ the game.

“Last Known Position is interesting, too,” he continues. “It’s almost our version of knocking on the wall in the old games, but it works as part of the action phase rather than the stealth phase. Some iterations of it were really powerful, where all the enemies would descend on your Last Known Position, all going ‘shit, what happened?’ It was almost too easy because you’d have a crowd of enemies, one grenade, and the section is over. We had to tweak how it worked and the whole progression of the AI.”

While Ubisoft Montreal was busy designing Splinter Cell’s new brand of stealth, Rocksteady was refining its own ideas for Arkham Asylum and Konami was creating a whole new way to play Metal Gear Solid. Both games attracted the team’s attention but neither changed the fifth Splinter Cell. “What I like about our game is that you’re in control of when it becomes about action. You’re the stealth guy, you can prepare, you can take your time, mark your guys and you’re ready. I think we’ve got a lot of different loops that are interesting. We’ve got the stealth loop, the action loop, the vanishing loop, and then if you’re able to vanish the AI go into search mode. You’re still the predator and still hiding but now they’re moving around more so it’s more dangerous.

“You could play almost all of Metal Gear Solid 4 as a shooter,” says Beland with a hint of disappointment. “I think that was their way of changing stealth but to me, Batman was the game that really delivered a new take on stealth. They have the – I call it the ‘eject button’, right? – the grappling hook. You can just zip away and you’re out, which is a very Batman feeling. I love that game.”

Beland worked for ten months on the original Assassin’s Creed and left with one overriding lesson drawn from reviews and fan feedback – Assassin’s Creed was a game without variety and so variety would be absolutely key to Conviction’s campaign. But as he lists the game’s more radical and varied moments it’s clear he’s listing the worst parts of the game. “There’s the Iraq map, then the Memorial with the spotters, the Washington Monument chase – little moments that break up the pace and give you a bit more variety,” says Beland.

Conviction’s basic mechanics were good enough that the game suffered during those moments of variety, and is the reason why those later stages were weaker than the earliest ones. The EMP Staging Grounds and White House levels are the game at its most linear, where your options are fewer and the game’s interesting systems can’t be so easily exploited. Beland goes on to describe how map design on later stages was dictated by their choice of location; how the White House has fewer big rooms and exits than earlier stages like the Maltese museum or Whitebox Laboratory.

“You’re kind of screwed with that,” he says. “But at the same time I think it’s interesting because it gives variety.” It worked for the game’s structure, building from open-ended stealth in those early levels to an intense final battle where your options are limited, but it’s a design process entirely opposite to the one behind the game’s cooperative maps.