THE LOST INTERVIEW

By Nick Setchfield

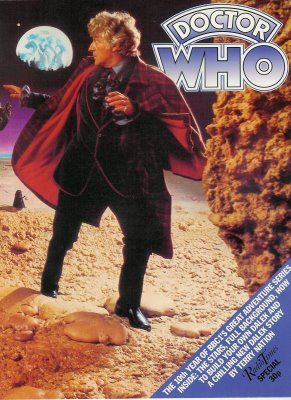

With the classic Jon Pertwee Doctor Who tales Frontier In Space and Planet Of The Daleks arriving on DVD as the Dalek War box set, here's another chance to read our 'lost' interview with the great man, originally conducted in 1986 but not published until our 2008 Doctor Who Special.

Jon Pertwee was the first famous person I ever interviewed, and only now does it feel like that moment in The Empire Strikes Back where a squeaky, inexperienced Luke Skywalker rushes to confront Darth Vader, too soon, all too soon.

It was January 1986, an impossible 22 years ago. Pertwee was in my hometown of Cardiff, appearing as Spottyman in that majestically titled slice of musical theatre known as Superted and the Comet of the Spooks. He agreed to an interview for my fanzine, and, one evening, welcomed my friend Anthony and I backstage with a charitable amount of time and charm. And bless him for that, for the tape now reveals a grimly amateur interview technique, all teenage stumble and hesitancy (you're never quite as suave as you imagine you are when you're 17, are you?) But hey, it's perfectly understandable. At one point a barefoot Melvyn Hayes popped into the dressing room, and I knew I was breathing the very oxygen of showbusiness.

The interview was never published. A levels and university came and my once all-consuming hobby withered. The tape wasn't so much lost as buried beneath a pile of life.

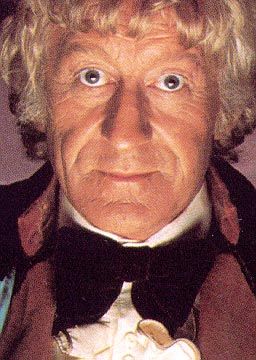

What's ironic is that in 1986 I had to fight to remind myself that I was in the presence of the Third Doctor - Pertwee cut a peculiar figure in his towelling dressing gown, outsized spectacles balanced on that iconic beak, his face daubed with garish greasepaint spots for that night's performance. But now, 22 years on, I hear that voice and I only see him in his familiar velvet jacket, his dandy cuffs, his cape that encompassed the cosmos. It's the voice of a childhood hero, and the face that beamed, twinkly and wise, from a time-tunneling title sequence that defined my Saturdays.

He made us switch the tape off when he shared his thoughts on Tom Baker, though.

What qualities do you think producer Peter Bryant saw in you which led him to cast you as the Doctor?

I know for a fact. We had a big luncheon on the 20th anniversary. And I said to Peter, 'What on Earth was it about me that made you think of me for Doctor Who?' And he said, 'Oh, your ability to play the guitar and sing songs and do funny voices.' And I said, 'Dear God, you weren't expecting Doctor Who to be like that, were you?' He said 'Yes, I was!' And he really intended to have me as a kind of musical Doctor Who, to play the guitar and sing folk songs, and all of the strange things that he'd seen me do. And I said 'Oh, I wouldn't have done that anyway... The whole idea of doing Doctor Who for me was to get away from that.' I've just recently learned that their first choice was Ron Moody!

And after you left they were apparently trying to get Jim Dale and Richard Hearne, alias Mr Pastry...

Richard Hearne? To play Doctor Who? (incredulous). Well, he died very soon after. He would have been a very dead Doctor.

Did you ever consider playing the Doctor with a funny voice, or in disguise, as Patrick Troughton originally did?

No, no, never. In fact we had this ridiculous conversation with the head of programmes, Shaun Sutton, who's a very old friend of mine. He said 'Do you want the job?' And I said 'I'm not too sure now - how do you want it played?' And he said 'As Jon Pertwee!' I said, 'Who the Hell's that?' Because I didn't know who I was, vocally. I'd never played myself in anything, not without some sort of disguise, whether vocal or physical. So we had a bit of an impasse before I eventually agreed to do it. But in my first story I went through quite a trauma trying to find a character - that scene in the shower, with the funny shower cap on, and the trying out of the hats and making faces in the mirror... I took one look at that and thought 'No, that's the last we'll have of that!'

Was there any pressure on you at the beginning to play it in a more comic way?

No, not at all. There was a slightly comic aspect to that first one - running down the hill in that wheelchair, for instance - but when Barry Letts took over we very quickly dropped it. The only pressure put on me was by Barry, who didn't think I was taking the job very seriously. But after a while he realised that was simply the way I worked, and that I get a lot more out of people by making them laugh and have a good time. He'd say 'I really think we ought to work harder and concentrate more on the job.' And I said 'Nobody could be concentrating on the job harder than I am - you just haven't learned to read me yet.' And eventually we became very good friends.

When did the fan mail and recognition start?

Almost immediately. Certainly within two weeks of it going on air. I got the sort of letters that said 'I always thought Pat Troughton was the only Doctor Who until I saw you...' Mark you, I had a great advantage over the rest in that I was the first in colour. It makes a tremendous difference when suddenly zap, you're hit with this flamboyant character with this jazzy costume and colours and very pretty girls. And now, of course, I get enormous fan mail from America, and they will all be saying exactly the same thing - 'I always thought Tom Baker was the only Doctor Who...'

Did you have any frustrations with the show?

With the money they had to spend, other planets looked silly most of the time. The quarries were alright, but the buildings were awful, or the caves, with remarkable hard concrete floors. You'd think, 'Who's been along here and put down a lot of cement and concrete?' It was ridiculous. Chuck some sand down, or some earth! Let's try and keep a reality! But this is one of the reasons why it's so popular in America, because it has that homespun feeling about it.

Is it true that you used to struggle with the more technical lines?

I couldn't remember the line 'Reverse the polarity of the neutron flow' until I thought of 'Polish up the handles of the big front door', from Gilbert and Sullivan. I sang it, and then I could remember the line! I used to have my technical lines written up on the backs of furniture and cushions and on seats, behind anything I could. And then of course my dear and beloved friends would go and un-drawing pin it all, and shift it somewhere else. Many's the time I'd have to say 'Stop! Cut! Somebody's pinched my lines!'

Is it true that you once tried writing a script for Doctor Who yourself?

I did. I knew a very well known writer named Reed de Rouen - half Cherokee Red Indian, actually - and he and I wrote a complete Doctor Who, which we submitted, with great joy, because we knew it was extremely good. It was bloody good, a very exciting story. We gave it to Terrance Dicks, and he said 'Very nice indeed, very exciting.' I said, 'Are you going to do it?' And he said 'No - it's completely wrong in its construction.' Doctor Who has a very special way of being constructed - it builds all the time, going backwards and forwards between characters. We'd written a progressive film script. Now you can write a film script that way, but you can't write television like that - you've got to keep reminding people of what's going on, you've got to go back and pick up and pick up and pick up, and then you go 'boom!' at the end and everyone comes together. We hadn't done that. We'd written a very good film script, and it was quite unadaptable. It was all about the Arctic, and all took place in snow and ice and in ice tunnels. I've forgotten what it was called. I've got it at home somewhere...

Ever considered marketing it?

What a very good idea! I sell everything in America... You're quite right! I must market it at once! What a splendid scheme! Thank you very much! If I sell a lot I shall give you a present!

What was it about Roger Delgado that made him so special?

His gentleness made him special. He was one of the most gentle people I ever knew, which was extraordinary, really, because he was the most terrifying man as a villain, with these wonderful eyes and this marvelous face and great voice. He was a dear, gentle soul. He wasn't a heroic figure, far from it. Quite the opposite. But he was a very fine, natural actor. When Roger was killed it was a terrible blow to me, because he was one of my greatest friends.

And what was special about Katy Manning?

She was a sort of magic lunatic. She was a very highly charged young lady, of tremendous temperament, which would either be fizzling along nicely or would go off like a real whizz-bang. She had the most extraordinary sparky temperament, probably because she was brought up by Judy Garland and Liza Minnelli. Liza was her mate and they were kids together. Anyone brought up by Judy Garland is bound to be a bit eccentric! And Katy was a complete eccentric. As I am too, we got on terribly well together. She had moments of absolute genius, where she was wonderful, and then moments where she was deplorable. But I liked that, rather than someone being fairly good all of the time - I liked that kind of magic spark, the moments where you get something quite magical.

Why did you leave?

I think I asked for some more money. And they said they didn't think they would want to pay me any more money. And so I said 'Oh well, if that's the case, I won't be staying on.'

What did you think of your successors in the role?

Never ever ask an actor that question. Say I answered that question and I said 'I think Peter Davison is a twit and inarticulate and has no character.' Say I said that and you said 'I was interviewing Jon Pertwee the other day, Peter, and he said you were inarticulate'... Can you imagine what kind of situation is going to develop when I have to work with him again? So irrespective of what one thinks, no actor of any intelligence would give an opinion about another actor's work. It's like an all-in wrestler. You don't really kick an all-in wrestler in the crutch. You pretend you do, but if you do he'll kick you straight back the next time he fights you. But I get on well with everyone I've ever worked with in Doctor Who. Pat and I had a problem in finding how to work with each other when we did The Three Doctors, because Pat doesn't work rigidly to positive cue, whereas I do. He'd give me a cue line and I'd say 'What's that?' He'd say 'What's what?' He'd be under the TARDIS or something. I'd say 'What did you just say to me?' He'd say 'That's the line...' I'd say 'No it isn't!' And then he'd say 'Well, it's near enough...' (laughs). Marvelous, brilliant actor, but he works that way, very relaxed, very easy, and he paraphrases.

Your career's spanned radio, film, television and live performance. Do you have a preference?

Yes, I always prefer live audiences. I work in cabaret, all over the world, and there's nothing better than cabaret when it's good, and nothing worse than cabaret at its worst, because if you die in cabaret it's the most dreadful feeling, because you're on your own. But if you succeed, as I do, in places like Australia and Canada and New Zealand and Kenya, when it's successful there's nothing more exhilarating than to have an hour and a half on a floor on your own, holding that audience and knowing that you're entertaining them. But equally if you try to do cabaret in London and you go to Grosvenor House or the Dorchester or wherever, where the big cabaret venues were - I say were, because hardly anybody works there anymore - it was purgatory, because nine times out of ten, they considered you an intrusion. They're there with a girlfriend, or somebody else's wife, and they don't want you there, because you're an intrusion into what they want to do, which is snog and eat and get pissed. So the cabaret scene in England has always been terribly, terribly difficult.

What were your experiences?

I played all the top venues like the Cafe de Paris and Quaglino's, all the tip-top clubs in the days when cabaret was at its height, and it was hell even then. The Savoy Grille was good because people didn't have the faintest idea who you were, they were all the gentry from the country and they'd say "Damn good, this fellow, who is he? Peewit? Never heard of him..." And they'd fall about and be an easy pushover audience. But when the uprise of youth started and money got into young people's pockets, which it never did before - nobody had any money when I was a young man, except family money - once the moneyed young people happened in the West End of London it was hell. They just shouted at you, or didn't listen, or the girls thought it was the thing to do to smoke endless cigarettes all the way through your act. So most people gave it up. It started all over the provinces, when the gambling started, all these clubs mushrooming. A lot of money was spent, and to begin with it was wonderful but then it became deplorable and now it's finished, absolutely finished. Nobody will go there. The comics are all too dirty - you can't go there with a clean act, no one will listen to you.

You were in a number of Carry On movies...

Yes, but I didn't ever want to be attached to them because once you were in a Carry On you became a member of the team, and once you became a member of the team you never worked for any other film company in the world. If you think of the career of an actor of the calibre of Kenneth Williams... Kenneth Williams is, in fact, a quite brilliant, brilliant actor. He did some superb plays in the West End and got awards as a straight actor. Then he went into the Carry Ons and did so many of them that he became somewhat of a caricature and has stayed that way. It's fine - he's very gainfully employed at all times, but the fact is that it obscured his prowess as a real actor, like Sid James was, or Joan Sims, who worked with me in Worzel Gummidge and is a magnificent actress, but she did those things for so long that no one could think of her doing anything else. So that's why I did three very small cameos, and then when I was asked to do more I said no, I didn't want to do it.

How do you choose your projects these days?

I'm much more careful now with what I do, and often I realise I'm doing things where I don't know why I'm bothering to do them, except financially. I've really always been a commercially minded actor, otherwise I now would have been at the National, or down in Chichester, doing those seasons. Which I would enjoy but, frankly, I chose the money, always. I chose the things that paid better.

No yearning to play Hamlet, then?

Absolutely none! I've got a yearning not to play it!

Nick Setchfield